-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

N. Barkham, K. O. Kong, A. Tennant, A. Fraser, E. Hensor, A. M. Keenan, P. Emery, The unmet need for anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy in ankylosing spondylitis, Rheumatology, Volume 44, Issue 10, October 2005, Pages 1277–1281, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh713

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objectives. Anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy is effective in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis (AS), but guidelines are needed because of the cost. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the proportion of patients with AS who meet the criteria for anti-TNF therapy as well as to explore the relationship between disease activity, health status and quality of life in patients with AS who would potentially meet the criteria compared with those who would not.

Methods. All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AS were identified via a search through the clinic correspondence database and sent postal questionnaires. Data captured included demographics, disease activity, aspects of functional impairment, activity limitation and quality of life using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), pain scores (using a visual analogue scale), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), short-form 36 (SF-36) and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL) questionnaire. The unpaired Student's t-test, χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U-test were performed for comparisons of groups where appropriate.

Results. Out of 325 mailed questionnaires, 246 (76%) were returned. The mean age of the patients who replied to the questionnaire was 52 yr (±12 yr) and 25% (62) were females. Mean BASDAI was 49 (±24) and 64% had a BASDAI ≥ 40. There were significant differences between the groups with a BASDAI above and below 40 in pain by VAS, functional ability (BASFI, HAQ), health status (SF-36) and quality of life (ASQoL). Almost two-thirds (64%) of patients would meet the criteria for anti-TNF therapy under recommended guidelines.

Conclusion. Patients with AS demonstrated poor functional status and poor quality of life. There is a large unmet need for effective therapy in AS, with almost two-thirds of patients meeting the proposed criteria for biological therapy. Patients with a BASDAI ≥ 40 had a worse functional status and quality of life than those who have a BASDAI of <40. These results indicate that the need for effective intervention for AS is a priority area.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of joints and entheses associated with a significant reduction in quality of life [1, 2], health status [3, 4] and working ability [5–9]. It is substantially more prevalent than previously estimated, with estimates as high as 1% in Caucasians [10]. Until recently, delayed diagnosis was usual, due to the insensitivity of radiographs, and therapeutic options were limited to physical therapy and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) being ineffective for axial disease [11–13]. While AS has a considerable impact at both the individual and community level it has received little attention, probably due to the commonly held assumption of a good clinical outcome [7] and difficulty in diagnosing it early. This assumption has recently been challenged, with data showing that 70% of patients progress to fusion of the spine over 10 to 15 yr [14–16]. Furthermore, the availability and efficacy of anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy has heralded a new era for the treatment of AS [17].

While the optimal use of anti-TNF agents in patients with AS has yet to be defined, two key bodies, the Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis Working Group (ASAS) [18] and the British Society of Rheumatology (BSR) [19], have recommended criteria for AS patients receiving anti-TNF therapy. The criteria for therapy recommended by both groups are presented in Table 1. The guidelines for both bodies recommend that a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) ≥ 40 should be used as one of the selection criteria for patients receiving anti-TNF therapy. The aim, therefore, of this study was to determine the incidence of AS patients who demonstrated a BASDAI ≥ 40 and to describe the impact of the disease on functional status and quality of life in these patients compared with those patients having a BASDAI of <40.

European guidelines for prescribing TNF-α blockers in adults with AS

| ASAS Working Group | Active disease for ≥ 4 weeks |

| criteria [18]: | BASDAI ≥ 40 sustained for 4 weeks |

| Failure of NSAIDs | |

| Expert opinion | |

| BSR criteria [19]: | BASDAI ≥ 40 sustained for 4 weeks |

| Failure of NSAIDs | |

| Spinal pain VAS ≥ 4 cm |

European guidelines for prescribing TNF-α blockers in adults with AS

| ASAS Working Group | Active disease for ≥ 4 weeks |

| criteria [18]: | BASDAI ≥ 40 sustained for 4 weeks |

| Failure of NSAIDs | |

| Expert opinion | |

| BSR criteria [19]: | BASDAI ≥ 40 sustained for 4 weeks |

| Failure of NSAIDs | |

| Spinal pain VAS ≥ 4 cm |

Methods

Study design

We performed a cross-sectional study of all patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AS seen from 2001 to 2003 in the rheumatology out-patient clinic at Leeds General Infirmary. The secondary care population served by this department is approximately 800 000, with further tertiary referrals coming from outside the region, which captures a population of over 4 million. Approval for the study had been obtained from the local research ethics committee. Patient were identified via manual and computer search through the clinic correspondence database. The inclusion criterion was a confirmed diagnosis of AS based on modified New York classification criteria [20, 21]. Questionnaires were mailed to all the identified patients. Completed questionnaires were returned using pre-addressed, pre-stamped envelopes. Reminder letters and a second copy of the same questionnaire were sent to those patients who did not reply within 2 months.

In order to assess the role of the expert opinion, a subgroup of patients from our clinic were analysed. Thirty consecutive clinic attendees with a diagnosis of AS (based on the New York criteria) were asked to fill out a set of questionnaires including BASDAI. All patients were then assessed by a consultant rheumatologist and classified as either appropriate or not for biological treatment, with a clinical rationale provided for each case.

Data collection

The questionnaires were design to assess the whole experience of the disease and included: BASDAI [22]; patient self-assessed disease activity and pain over the past 7 days using 100 mm visual analogue scales (VAS); information about work activities using open-ended questions and the Work Instability Scale [23]; the Medical Outcomes Study short-form 36 (SF-36) [24–27]; the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) score [28]; the Standford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [29, 30]; and quality of life using the Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL) questionnaire [1].

Statistical analysis

Data were explored and evaluated for parametric and non-parametric analysis. Both mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) and median (range) are presented for continuous and ordinal data, while categorical data are presented as the absolute count and percentage. Analysis of the data was done using SPSS for Windows version 11.0. The unpaired Student's t-test, χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U-test were performed for comparisons of groups where appropriate. Pearson's and Spearman's correlation coefficients were calculated where indicated. The significance level was set at 0.01.

Results

Patient characteristics

All patients surveyed were diagnosed by a consultant rheumatologist as having AS according to the New York criteria for AS; 8.7% were diagnosed with skin psoriasis and 1.6% with inflammatory bowel disease.

Out of the total of 325 patients identified, 213 (66%) replied during the first round and another 33 (10%) returned completed questionnaires after the reminder letters, giving a total response rate of 76% of those who were identified through the Leeds database. The mean age of the 246 patients who replied to the questionnaire was 52 yr (±12 yr), 25% (62) were females and the mean duration of symptoms was 19.4 yr. The mean age of 79 non-responders was 46 ± 14 yr, which is significantly younger than the responders, while the proportion of female was similar (28%).

Disease activity

The disease activity score based on BASDAI was normally distributed with mean of 49 ± 24 and 64% had a BASDAI ≥ 40. This is comparable with data from previous literature from the UK [31–33] and Europe [6]. Inflammatory back pain over the past week as measured using VAS for nocturnal pain was 42 ± 28 while the mean patient's global assessment of disease activity was 46 ± 25. All three measures, which reflect disease activity, correlated strongly with each other (correlation coefficient ranging from 0.71 to 0.80, P<0.001).

Impairment

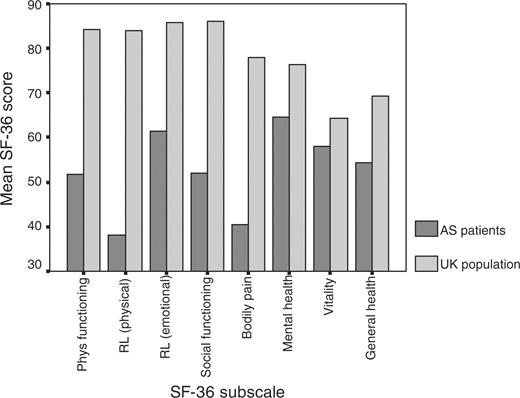

The SF-36 scores for pain and vitality subscales reflected the severity experienced by those with AS compared with control scores matched for age and sex from the UK normal population (Fig. 1) [34]. The mental health of these patients was also adversely affected (mean score of 63 ± 21)(Fig. 1).

Activity limitation

The BASFI displayed a uniform distribution, with a mean BASFI of 50 ± 28. Significantly more patients with active disease (BASDAI ≥ 40) had poor functional status (BASFI ≥ 40) (χ2 = 86.2, df = 1, P<0.001) (Table 2). The range of HAQ was from 0 to 3 with a median of 0.875, which signifies moderate disability. All measures of activity limitation were highly correlated (Spearman's ρ = 0.85–0.90, P<0.001). The SF-36 physical function subscale levels of functioning were found to be worse than that of the normal UK population (Fig. 1) [34].

Comparing functional ability, quality of life and health status between the groups with BASDAI < 40 and BASDAI ≥ 40

| . | BASDAI<40 . | . | BASDAI ≥ 40 . | . | Total . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | P value* . | |||

| BASFI | 28.01 ± 24.13 | 21.1 (0–96.4) | 62.09 ± 21.88 | 64.7 (5.6–97.6) | 49.49 ± 28.04 | 49.8 (0–97.6) | <0.001 | |||

| HAQ | 0.48 ± 0.57 | 0.25 (0–2.25) | 1.25 ± 0.66 | 1.25 (0–2.88) | 0.97 ± 0.74 | 0.88 (0–2.88) | <0.001 | |||

| ASQoL | 4.25 ± 4.19 | 3 (0–18) | 12.29 ± 4.34 | 13 (1–18) | 9.35 ± 5.79 | 10 (0–18) | <0.001 | |||

| SF-36 | ||||||||||

| Physical function | 71.90 ± 25.56 | 80 (0–100) | 38.59 ± 26.58 | 40 (0–95) | 51.09 ± 30.82 | 50 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-physical | 66.09 ± 36.76 | 75 (0–100) | 21.58 ± 33.56 | 0 (0–100) | 38.45 ± 40.95 | 25 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Bodily pain | 58.78 ± 21.67 | 62 (12–100) | 22.74 ± 15.76 | 21.5 (0–100) | 35.98 ± 25.14 | 22 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Vitality | 49.71 ± 19.59 | 50 (0–90) | 29.08 ± 17.91 | 30 (0–80) | 36.84 ± 21.19 | 35 (0–90) | <0.001 | |||

| General health | 50.10 ± 21.19 | 52 (5–90) | 31.10 ± 18.24 | 30 (0–97) | 38.24 ± 21.57 | 35 (0–97) | <0.001 | |||

| Social function | 79.17 ± 22.28 | 87.5 (12.5–100) | 48.27 ± 27.41 | 50 (0–100) | 59.50 ± 29.72 | 62.5 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Mental health | 73.20 ± 17.75 | 76 (24–100) | 56.62 ± 19.75 | 60 (0–96) | 62.85 ± 20.57 | 64 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-emotional | 83.72 ± 30.57 | 100 (0–100) | 48.86 ± 43.45 | 33.33 (0–100) | 61.97 ± 42.48 | 100 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| . | BASDAI<40 . | . | BASDAI ≥ 40 . | . | Total . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | P value* . | |||

| BASFI | 28.01 ± 24.13 | 21.1 (0–96.4) | 62.09 ± 21.88 | 64.7 (5.6–97.6) | 49.49 ± 28.04 | 49.8 (0–97.6) | <0.001 | |||

| HAQ | 0.48 ± 0.57 | 0.25 (0–2.25) | 1.25 ± 0.66 | 1.25 (0–2.88) | 0.97 ± 0.74 | 0.88 (0–2.88) | <0.001 | |||

| ASQoL | 4.25 ± 4.19 | 3 (0–18) | 12.29 ± 4.34 | 13 (1–18) | 9.35 ± 5.79 | 10 (0–18) | <0.001 | |||

| SF-36 | ||||||||||

| Physical function | 71.90 ± 25.56 | 80 (0–100) | 38.59 ± 26.58 | 40 (0–95) | 51.09 ± 30.82 | 50 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-physical | 66.09 ± 36.76 | 75 (0–100) | 21.58 ± 33.56 | 0 (0–100) | 38.45 ± 40.95 | 25 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Bodily pain | 58.78 ± 21.67 | 62 (12–100) | 22.74 ± 15.76 | 21.5 (0–100) | 35.98 ± 25.14 | 22 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Vitality | 49.71 ± 19.59 | 50 (0–90) | 29.08 ± 17.91 | 30 (0–80) | 36.84 ± 21.19 | 35 (0–90) | <0.001 | |||

| General health | 50.10 ± 21.19 | 52 (5–90) | 31.10 ± 18.24 | 30 (0–97) | 38.24 ± 21.57 | 35 (0–97) | <0.001 | |||

| Social function | 79.17 ± 22.28 | 87.5 (12.5–100) | 48.27 ± 27.41 | 50 (0–100) | 59.50 ± 29.72 | 62.5 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Mental health | 73.20 ± 17.75 | 76 (24–100) | 56.62 ± 19.75 | 60 (0–96) | 62.85 ± 20.57 | 64 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-emotional | 83.72 ± 30.57 | 100 (0–100) | 48.86 ± 43.45 | 33.33 (0–100) | 61.97 ± 42.48 | 100 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

*Mann–Whitney U-test: comparing between BASDAI<40 and BASDAI ≥ 40.

Comparing functional ability, quality of life and health status between the groups with BASDAI < 40 and BASDAI ≥ 40

| . | BASDAI<40 . | . | BASDAI ≥ 40 . | . | Total . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | P value* . | |||

| BASFI | 28.01 ± 24.13 | 21.1 (0–96.4) | 62.09 ± 21.88 | 64.7 (5.6–97.6) | 49.49 ± 28.04 | 49.8 (0–97.6) | <0.001 | |||

| HAQ | 0.48 ± 0.57 | 0.25 (0–2.25) | 1.25 ± 0.66 | 1.25 (0–2.88) | 0.97 ± 0.74 | 0.88 (0–2.88) | <0.001 | |||

| ASQoL | 4.25 ± 4.19 | 3 (0–18) | 12.29 ± 4.34 | 13 (1–18) | 9.35 ± 5.79 | 10 (0–18) | <0.001 | |||

| SF-36 | ||||||||||

| Physical function | 71.90 ± 25.56 | 80 (0–100) | 38.59 ± 26.58 | 40 (0–95) | 51.09 ± 30.82 | 50 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-physical | 66.09 ± 36.76 | 75 (0–100) | 21.58 ± 33.56 | 0 (0–100) | 38.45 ± 40.95 | 25 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Bodily pain | 58.78 ± 21.67 | 62 (12–100) | 22.74 ± 15.76 | 21.5 (0–100) | 35.98 ± 25.14 | 22 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Vitality | 49.71 ± 19.59 | 50 (0–90) | 29.08 ± 17.91 | 30 (0–80) | 36.84 ± 21.19 | 35 (0–90) | <0.001 | |||

| General health | 50.10 ± 21.19 | 52 (5–90) | 31.10 ± 18.24 | 30 (0–97) | 38.24 ± 21.57 | 35 (0–97) | <0.001 | |||

| Social function | 79.17 ± 22.28 | 87.5 (12.5–100) | 48.27 ± 27.41 | 50 (0–100) | 59.50 ± 29.72 | 62.5 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Mental health | 73.20 ± 17.75 | 76 (24–100) | 56.62 ± 19.75 | 60 (0–96) | 62.85 ± 20.57 | 64 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-emotional | 83.72 ± 30.57 | 100 (0–100) | 48.86 ± 43.45 | 33.33 (0–100) | 61.97 ± 42.48 | 100 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| . | BASDAI<40 . | . | BASDAI ≥ 40 . | . | Total . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | Mean ± s.d. . | Median (range) . | P value* . | |||

| BASFI | 28.01 ± 24.13 | 21.1 (0–96.4) | 62.09 ± 21.88 | 64.7 (5.6–97.6) | 49.49 ± 28.04 | 49.8 (0–97.6) | <0.001 | |||

| HAQ | 0.48 ± 0.57 | 0.25 (0–2.25) | 1.25 ± 0.66 | 1.25 (0–2.88) | 0.97 ± 0.74 | 0.88 (0–2.88) | <0.001 | |||

| ASQoL | 4.25 ± 4.19 | 3 (0–18) | 12.29 ± 4.34 | 13 (1–18) | 9.35 ± 5.79 | 10 (0–18) | <0.001 | |||

| SF-36 | ||||||||||

| Physical function | 71.90 ± 25.56 | 80 (0–100) | 38.59 ± 26.58 | 40 (0–95) | 51.09 ± 30.82 | 50 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-physical | 66.09 ± 36.76 | 75 (0–100) | 21.58 ± 33.56 | 0 (0–100) | 38.45 ± 40.95 | 25 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Bodily pain | 58.78 ± 21.67 | 62 (12–100) | 22.74 ± 15.76 | 21.5 (0–100) | 35.98 ± 25.14 | 22 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Vitality | 49.71 ± 19.59 | 50 (0–90) | 29.08 ± 17.91 | 30 (0–80) | 36.84 ± 21.19 | 35 (0–90) | <0.001 | |||

| General health | 50.10 ± 21.19 | 52 (5–90) | 31.10 ± 18.24 | 30 (0–97) | 38.24 ± 21.57 | 35 (0–97) | <0.001 | |||

| Social function | 79.17 ± 22.28 | 87.5 (12.5–100) | 48.27 ± 27.41 | 50 (0–100) | 59.50 ± 29.72 | 62.5 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Mental health | 73.20 ± 17.75 | 76 (24–100) | 56.62 ± 19.75 | 60 (0–96) | 62.85 ± 20.57 | 64 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

| Role-emotional | 83.72 ± 30.57 | 100 (0–100) | 48.86 ± 43.45 | 33.33 (0–100) | 61.97 ± 42.48 | 100 (0–100) | <0.001 | |||

*Mann–Whitney U-test: comparing between BASDAI<40 and BASDAI ≥ 40.

Participation

Among the SF-36 subscales assessing participation, limitation of role due to physical health was the worst affected (Table 2). The disease was shown to have less impact on role-emotional and social functioning subscales, although scores were still poorer than that of the UK normal population (Fig. 1) [34].

Quality of life

The ASQoL had a median score of 10, with a range of 0–18: this is similar to data from previous literature [1]. During its development the ASQoL was shown to correlate well with the Nottingham Health Profile sections for physical mobility (Spearman rank correlation coefficient 0.78) and pain (0.81) and the BASFI (0.72).

Ability to work

While 84% of AS patients were in the working age group (18–65 yr), 19% of patients had lost their job because of the disease, 10% had retired early and 6% were home carers. Of the 120 patients in work 80% were in full-time and 20% were in part-time employment. Of these, 78% reported a change in their working pattern or the shortening of their working hours due to the disease. Overall, in those working, 45% showed a Work Instability Score (WIS) ≥ 10, indicating at least a moderate risk of impending job loss and 17% were at high risk (WIS ≥ 17).

Of those working 49% had active disease (BASDAI>40) and were shown to have a significantly higher risk of work instability as assessed by the Work Instability Scale (P<0.001). The WIS also identified a group of patients who were at risk of job loss even though the disease activity was not considered high (<40). BASDAI ≥ 40 had a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 72% to moderate risk of job loss as expressed by a WIS of ≥10.

Anti-TNF therapy BASDAI cut-off score

The health status of patients with a BASDAI of ≥40 was compared with that in patients with a BASDAI of <40. There were highly significant differences between the groups defined with respect to levels of impairment (pain and SF-36 bodily pain, mental health and vitality subscales); functional ability (BASFI and HAQ), participation (SF-36 role-physical, role-emotional and social functioning subscales), quality of life (ASQoL) and, predictably, global disease activity as assessed using VAS. The means, medians and statistical differences are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

Patients surveyed in this study were recruited from a secondary care clinic. While such patients cannot be directly compared with those selected and recruited for AS clinical trials, it is important to note that this group of AS patients demonstrated a very poor health status and quality of life for their age. Notably, measures of health status for this group were worse than those published for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [35] and are consistent with the findings of Zink et al. [2].

Despite the disabling nature of the condition, 56% of patients were still in employment. However, 28% of these patients were shown to be currently at moderate risk and 17% at high risk of losing their jobs according to the WIS. The WIS does not have longitudinal validation in AS and further work is needed to demonstrate that biological therapies can influence work instability in AS.

In terms of the recommended criteria for anti-TNF therapy, almost two-thirds of patients had a BASDAI of ≥40. Eighty-six per cent were on NSAIDs and 27% were on DMARDs. Sixty-four per cent would meet all BSR criteria for disease activity and all bar the expert opinion for the ASAS criteria, suggesting a need for anti-TNF therapy.

Although a BASDAI ≥ 40 is an arbitrary cut-off for biological therapy, BASDAI ≥ 40 appears robust as it discriminated across every aspect of patients' experience, including impairment, activity limitation, participation and quality of life. It should be noted, however, that there was a positive correlation between increasing BASDAI scores and indicators of impairment, participation and quality of life and that other BASDAI cut-off scores may also be discriminatory.

It must be acknowledged that the both the BSR and ASAS criteria for anti-TNF therapy also require the BASDAI to be repeated at 4 weeks. However, in patients not being treated with biological therapies the BASDAI tends to be stable over a 12-week period [17], therefore this requirement is unlikely to have much impact on the number requiring treatment. A subgroup analysis on patients from our clinic in whom an expert opinion was available showed that the opinion differed from the BASDAI in only 4 out of 30 cases (due to significant co-morbidity). Furthermore, the validity of a BASADAI of >40 as a criterion in selection for anti-TNF therapy has not yet been established. Our results do, however, demonstrate a significant difference in health status and quality of life in those patients above and below a BASDAI score of 40.

There are factors which predict response to biological therapy, such as shorter duration of disease, elevated C-reactive protein and higher BASDAI at entry [36], but none are sufficiently predictive of non-response to justify denying patients effective therapy.

Conclusion

AS has a substantial impact on patients in terms of function, impairment, activity limitation, participation and overall quality of life. Our study has demonstrated a large unmet need for effective therapy in AS: almost two-thirds of AS patients in our cohort were likely to meet the ASAS and BSR disease activity criteria for biological therapy. Given the reported efficacy and success of biological therapies, a considerable proportion of patients attending physicians with AS will have disease which may well benefit from the new biological therapies.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Doward LC, Spoorenberg A, Cook SA et al. Development of the ASQoL: a quality of life instrument specific to ankylosing spondylitis.

Zink A, Braun J, Listing J, Wollenhaupt J. Disability and handicap in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

Bostan EE, Borman P, Bodur H, Barca N. Functional disability and quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Ariza-Ariza R, Hernandez-Cruz B, Navarro-Sarabia F. Physical function and health-related quality of life of Spanish patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Boonen A, Chorus A, Miedema H. Withdrawal from labour force due to work disability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Boonen A, Chorus A, Miedema H, van der Heijde D, van der Tempel H, van der Linden S. Employment, work disability, and work days lost in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross sectional study of Dutch patients.

Boonen A, de Vet H, van der Heijde D, van der Linden S. Work status and its determinants among patients with ankylosing spondylitis. A systematic literature review.

Boonen A, van der Heijde D, Landewe R et al. Work status and productivity costs due to ankylosing spondylitis: comparison of three European countries.

Ward MM, Kuzis S. Risk factors for work disability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Braun J, Bollow M, Remlinger G et al. Prevalence of spondylarthropathies in HLA-B27 positive and negative blood donors.

Dougados M, van der Linden S, Leirisalo-Repo M et al. Sulfasalazine in the treatment of spondylarthropathy. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Abdellatif M. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo for the treatment of axial and peripheral articular manifestations of the seronegative spondylarthropathies: a Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study.

Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Weisman MH et al. Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. A Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study.

Gran JT, Skomsvoll JF. The outcome of ankylosing spondylitis: a study of 100 patients.

Brophy S, Mackay K, Al-Saidi A, Taylor G, Calin A. The natural history of ankylosing spondylitis as defined by radiological progression.

Carette S, Graham D, Little H, Rubenstein J, Rosen P. The natural disease course of ankylosing spondylitis.

Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial.

Braun J, Pham T, Sieper J et al. International ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti-tumour necrosis factor agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Paul S, Keat A. Assessment of patients with spondyloarthropathies for treatment with tumour necrosis factor alpha blockade.

van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria.

Goie The HS, Steven MM, van der Linden SM, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis: a comparison of the Rome, New York and modified New York criteria in patients with a positive clinical history screening test for ankylosing spondylitis.

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index.

Gilworth G, Chamberlain MA, Harvey A et al. Development of a work instability scale for rheumatoid arthritis.

Brazier J, Jones N, Kind P. Testing the validity of the Euroqol and comparing it with the SF-36 health survey questionnaire.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JFR, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs.

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study.

Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index.

Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation.

Pincus T, Summey JA, Soraci SA Jr, Wallston KA, Hummon NP. Assessment of patient satisfaction in activities of daily living using a modified Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire.

Mascarenhaus RF, Davis JM, Robertson LP. Eligibility for anti-TNF therapy in ankylosing spondylitis.

Mackenzie S, Miah D, Kane D, John H, Roger S. BASDAI assessment for anti-TNF therapy in ankylosing spondylitis.

Novak J, Griffiths A, Dawson JK, Abernathy VE. Profile of patients with ankylosing spondylitis attending a district general hospital—how many might be suitable for treatment with anti-TNF therapy?

Wiles NJ, Scott DG, Barrett EM et al. Benchmarking: the five year outcome of rheumatoid arthritis assessed using a pain score, the Health Assessment Questionnaire, and the Short Form-36 (SF-36) in a community and a clinic based sample.

Author notes

Academic Unit of Musculoskeletal Disease, Department of Rheumatology, First Floor, The General Infirmary, Great George Street, Leeds LS1 3EX and 1Academic Unit of Musculoskeletal Disease, Department of Rehabilitation, University of Leeds, 36 Clarendon Road, Leeds LS2 9NZ, UK.

- tumor necrosis factors

- ankylosing spondylitis

- activities of daily living

- biological therapy

- demography

- health status

- necrosis

- pain

- bathing

- diagnosis

- guidelines

- neoplasms

- quality of life

- visual analogue pain scale

- anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy

- pain score

- functional status

- functional impairment

- sf-36

Comments