-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

E. Hallert, M. Husberg, T. Skogh, Costs and course of disease and function in early rheumatoid arthritis: a 3-year follow-up (the Swedish TIRA project), Rheumatology, Volume 45, Issue 3, March 2006, Pages 325–331, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kei157

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objective. To calculate direct and indirect costs and to study disease activity and functional ability over 3 yr in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods. Three hundred and three patients with early (≤1 yr) RA were recruited during a period of 27 months (1996–1998). Data were recorded during 3 yr to assess disease activity, functional ability, medication, health-care utilization and days lost from work.

Results. Within 3 months, improvements were seen regarding all recorded variables assessing disease activity and functional ability, but 15% had sustained high or moderate disease activity throughout the study period. Indirect costs exceeded direct costs in all 3 yr. The average direct costs were € 3704 (US$ 3297) in year 1 and € 2652 (US$ 2360) in year 3. All costs decreased, except those for medication and surgery. Compared with men, women had more ambulatory care visits and used more complementary medicine. The indirect costs were € 8871 (US$ 7895) in year 1 and remained essentially unchanged; this was similar for both sexes. Almost 50% were on sick leave or early retirement at inclusion. Sick leave decreased but was offset by an increase in early retirement. The 14 patients who eventually received TNF inhibitors incurred higher costs even before prescription of anti-TNF therapy.

Conclusion. Disease activity and functional ability improved within 3 months after diagnosis of early RA. Direct costs decreased, except for medication and surgery. Indirect costs remained unchanged. Fifteen per cent of the patients had high or moderate disease activity in all 3 yr, indicating a need for more aggressive early anti-rheumatic therapy.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease associated with tissue destruction and functional disability [1–4]. The economic consequences of the disease are substantial for individuals and their families, and for the society as a whole [5–8]. Direct costs in terms of health-care utilization are increased, but costs are to a larger extent driven by indirect costs due loss of working capacity [9–12]. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Scandinavia is about 0.5–0.7%, women being more often affected than men [13, 14]. In Sweden, the total costs of RA in 1997 were estimated to be almost 3 billion Swedish kronor (SEK) (€ 315 million) [15] and in 2001 to 3.6 billion SEK (€ 390 million) [16]. In a recent study, the average total cost per patient during the first year of recent-onset RA was estimated to SEK 116 422 (€ 12 586), direct costs representing 31% and indirect costs 69% [17]. Drugs accounted for 9% of direct costs. Drug costs are, however, increasing substantially due to the increasing use of biological therapies [18]. Functional disability is associated with high direct and indirect costs [8, 19–21], and several studies report that early treatment limits joint destruction and improves functional outcome [22–24]. Modern management of RA therefore aims at early institution of potent anti-rheumatic pharmacotherapy. A recent study reported that long-term sick leave usually leads to early retirement, and failure to achieve early suppression of the disease is a strong predictor of permanent work disability [25]. In view of the unpredictable natural course of the disease, however, and the high costs and potential risk of adverse effects, it would be desirable to identify patients at high/low risk of an aggressive disease with poor outcome, as well as to identify potential responders/non-responders to different traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biological treatment modalities. Such knowledge would be very valuable in order to help individual tailoring or the optimal anti-rheumatic treatment.

The present study was done to calculate costs and to analyse disease activity and functional disability during the first 3 yr in recent-onset RA.

Patients and methods

Patients

All patients participated in a prospective cohort of recent-onset RA, i.e. the Swedish TIRA project [26]. TIRA is the Swedish acronym for ‘early intervention in rheumatoid arthritis’. Briefly, 320 subjects were enrolled between January 1996 and April 1998 from 10 rheumatology units in Sweden corresponding to a catchment area of 1 million inhabitants. All patients fulfilled at least four of seven criteria according to the 1987 ACR revised classification criteria [27] or had suffered from morning stiffness, symmetrical arthritis in small joints (fingers, wrists, toes). The duration of disease was ≤12 months at inclusion. All patients were assessed by a team care unit with a rheumatologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and nurse.

Disease

Clinical and laboratory variables were collected at inclusion and after 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months. Tender and swollen joint counts were recorded in a 28-joint score [28]. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and serum level of C-reactive protein (CRP) were analysed as well as isotype-specific (IgM and IgA) rheumatoid factors (RF) and antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP, second-generation CCP2 test). The physician assessed the global disease activity. Morning stiffness (minutes) and comorbidities were reported by the patient. Disease activity was also assessed by calculating the 28-joint count disease activity score (DAS-28) as described by Prevoo et al. [28].

Function and general health

The function of hands, upper limbs and lower limbs was evaluated by the range-of-movement index signals of functional impairment (SOFI) [29]. Walking velocity was measured by having the patient walk 20 m as fast as possible. The patients also completed the Swedish version of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [30] and assessed average pain and global well-being respectively on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS).

Medication

Ongoing, instituted and withdrawn medication with DMARDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids and analgesics was recorded at all visits. Drug treatment decisions were made by the physician's preference and reasons for withdrawing drugs were recorded as lack of effect or adverse side-effects.

Health-care questionnaire

Demographic and socio-economic data, including age, sex, marital status, formal educational level and employment status, were collected at study start. Marital status was rated as single or married/cohabiting. Educational level was rated as low (primary school level), medium (secondary school level) and high (college or university level). During the first and second years, the patients completed semi-annual questionnaires reporting health-care utilization over the last 6 months. All visits to health professionals, including type of professional, were reported, as were admissions to hospital and length of stay, surgical procedures, and the dosage and frequency of all drugs (prescribed and over the counter). In addition, all days lost from paid work due to illness and rehabilitation were reported. In the third year, one questionnaire was completed, reporting events over the previous 12 months. Data from the semi-annual questionnaires were put together and reported yearly. During the 3-yr follow-up, 44 patients had one missing biannual questionnaire. These questionnaires were completed with ambulatory visits, medication and sick-leave days according to the study protocol and medical records, in order to estimate the annual resource utilization.

Direct costs

During the first year, all patients had three visits each to physician, nurse, physiotherapist and occupational therapist, in total 12 visits according to the study schedule. The second year they had two planned visits to each professional (in total eight visits), and thereafter yearly (four visits in total). Unit costs for visits to physicians and other health professionals were rated using tariffs from the Swedish Federation of County Councils [31]. The cost for an ambulatory visit included all overheads, such as administration, laboratory tests, and X-ray and other equipment. Since the participating hospitals were of different sizes and the discharges varied to some extent, an average cost was calculated. A visit to a physician was estimated to cost SEK 2100 (€ 227) and to other health professionals SEK 700 (€ 76). Standard drug monitoring protocols were used in monitoring the patents for adverse reactions. The costs of surgery, including total costs of surgical interventions and a standardized number of hospital days, were calculated according to the NordDRG system [32]. Costs of additional hospitalization were calculated in the same manner, estimating a day in hospital at SEK 2800 (€ 302). Drug costs were calculated using dosage and duration multiplied by unit costs using market wholesale prices. All medication used for the disease and its complications were included. Costs of complementary medicine were estimated by the patient. All costs were calculated, applying a societal perspective, encompassing all costs, regardless of payer. Non-medical costs, such as costs of transportation and assistive devices, were not included in the present study.

Indirect costs

Indirect costs were calculated for subjects of working age (18–65 yr), using the human capital approach, estimating the value of lost production during the entire period of work absenteeism, assuming full productivity. Loss of productivity was calculated using the number of days with disability benefits, as reported by the patients. Patients who were unemployed (baseline, n = 14) or students (baseline, n = 6) were also entitled to the disability benefits and were included in the calculation of the indirect costs. The number of days was recalculated to equal full-time days. The cost of 1 month's full-time work was calculated using an average of the gross income of all gainfully employed Swedish full-time workers and corresponds to SEK 30 000 (€ 3243) (including taxes and other fees). Days of inability to perform work were estimated similarly for those with paid work and those with early retirement. All costs in the present study are presented in SEK and adjusted to 2001 values, using the consumer price index. The annual average 2001 was € 1 = SEK 9.25 = US$ 0.89.

Ethical considerations

All patients gave written informed consent to participation. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees of the participating hospitals.

Statistical analyses

Clinical and demographic data were presented as mean (s.d.), median, range and proportions. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the utilization of health-care and costs. Differences between groups were compared using Student's t-test calculated with the 95% confidence interval (CI) or the Mann–Whitney U-test when appropriate and within groups using paired t-test with 95% CI or Wilcoxon signed rank test. The χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used to test differences in proportions. All tests were two-tailed and P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical calculations were performed using SPSS 11.5 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical and socio-economic variables

Forty-four patients dropped out during the first 3 yr. Ten patients (3.1%) died, six moved from the area and 28 did not wish to participate further for various reasons. Subsequently, 276 (86%) patients reached the 3-yr follow-up. One hundred and ninety-five patients (71%) had health-care data at the 3-yr follow-up and 187 (68%) patients completed all questionnaires for all 3 yr (Table 1).

Number of patients in the TIRA study at follow-ups and number of patients completing health-care questionnaires

| . | Inclusion . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . | Data for all 3 yr . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients in the TIRA study | 320 | 297 | 284 | 276 | |

| Patients with health-care data | 303 | 276 | 254 | 195 | 187 |

| . | Inclusion . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . | Data for all 3 yr . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients in the TIRA study | 320 | 297 | 284 | 276 | |

| Patients with health-care data | 303 | 276 | 254 | 195 | 187 |

Number of patients in the TIRA study at follow-ups and number of patients completing health-care questionnaires

| . | Inclusion . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . | Data for all 3 yr . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients in the TIRA study | 320 | 297 | 284 | 276 | |

| Patients with health-care data | 303 | 276 | 254 | 195 | 187 |

| . | Inclusion . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . | Data for all 3 yr . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients in the TIRA study | 320 | 297 | 284 | 276 | |

| Patients with health-care data | 303 | 276 | 254 | 195 | 187 |

The dropouts from the TIRA study were older than the study group (64 vs 55 yr; P<0.0001), they walked more slowly (17 s vs 14 s; P = 0.04) and were to a larger extent living alone (P = 0.03).

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics were similar for responders and the non-responders of the health-care questionnaires, except for more non-responders living alone (P = 0.01). They assessed more morning stiffness 128 min vs 99 min (P = 0.01), but did otherwise not differ from the study group.

Ninety-five per cent of the patients fulfilled the 1987 ACR criteria at inclusion. Men were on average older and were more affected regarding function in hands and upper limbs compared with women. Approximately half of the patients were working or available to the workforce (Table 2). Most patients were living together with a partner (73% vs 59% in the general population). Comorbidity was reported in 32% of the women and 35% of the men. Cardiovascular disease was most frequent (43 patients), corresponding to 14% of all patients with recent-onset RA.

Sociodemographic data at baseline (mean and s.d. unless otherwise stated)

| . | Total . | Women . | Men . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | (n = 303) . | (n = 205) . | (n = 98) . |

| Age (yr) | 56 (15) | 55 (15) | 59 (14) |

| Educational level: n (%) | |||

| Primary school | 195 (66%) | 125 (63%) | 70 (72%) |

| Secondary school | 68 (23%) | 47 (23%) | 21 (21%) |

| College/university | 34 (11%) | 27 (14%) | 7 (7%) |

| Employment status: n (%) | |||

| Workinga | 94 (31%) | 71 (34%) | 23 (23%) |

| Sick leave | 85 (28%) | 58 (28%) | 28 (28%) |

| Early retired | 18 (6%) | 12 (5%) | 6 (6%) |

| Retired, ≥65 yr | 106 (35%) | 64 (31%) | 42 (43%) |

| . | Total . | Women . | Men . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | (n = 303) . | (n = 205) . | (n = 98) . |

| Age (yr) | 56 (15) | 55 (15) | 59 (14) |

| Educational level: n (%) | |||

| Primary school | 195 (66%) | 125 (63%) | 70 (72%) |

| Secondary school | 68 (23%) | 47 (23%) | 21 (21%) |

| College/university | 34 (11%) | 27 (14%) | 7 (7%) |

| Employment status: n (%) | |||

| Workinga | 94 (31%) | 71 (34%) | 23 (23%) |

| Sick leave | 85 (28%) | 58 (28%) | 28 (28%) |

| Early retired | 18 (6%) | 12 (5%) | 6 (6%) |

| Retired, ≥65 yr | 106 (35%) | 64 (31%) | 42 (43%) |

Seventeen patients did not complete health-care questionnaire at inclusion.

aIncluding 14 unemployed persons and six students.

Sociodemographic data at baseline (mean and s.d. unless otherwise stated)

| . | Total . | Women . | Men . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | (n = 303) . | (n = 205) . | (n = 98) . |

| Age (yr) | 56 (15) | 55 (15) | 59 (14) |

| Educational level: n (%) | |||

| Primary school | 195 (66%) | 125 (63%) | 70 (72%) |

| Secondary school | 68 (23%) | 47 (23%) | 21 (21%) |

| College/university | 34 (11%) | 27 (14%) | 7 (7%) |

| Employment status: n (%) | |||

| Workinga | 94 (31%) | 71 (34%) | 23 (23%) |

| Sick leave | 85 (28%) | 58 (28%) | 28 (28%) |

| Early retired | 18 (6%) | 12 (5%) | 6 (6%) |

| Retired, ≥65 yr | 106 (35%) | 64 (31%) | 42 (43%) |

| . | Total . | Women . | Men . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | (n = 303) . | (n = 205) . | (n = 98) . |

| Age (yr) | 56 (15) | 55 (15) | 59 (14) |

| Educational level: n (%) | |||

| Primary school | 195 (66%) | 125 (63%) | 70 (72%) |

| Secondary school | 68 (23%) | 47 (23%) | 21 (21%) |

| College/university | 34 (11%) | 27 (14%) | 7 (7%) |

| Employment status: n (%) | |||

| Workinga | 94 (31%) | 71 (34%) | 23 (23%) |

| Sick leave | 85 (28%) | 58 (28%) | 28 (28%) |

| Early retired | 18 (6%) | 12 (5%) | 6 (6%) |

| Retired, ≥65 yr | 106 (35%) | 64 (31%) | 42 (43%) |

Seventeen patients did not complete health-care questionnaire at inclusion.

aIncluding 14 unemployed persons and six students.

Disease and function over 3 yr

At inclusion, the patients had active arthritis with an average DAS-28 of 5.3. Highly significant improvements were seen after 3 months, as reported in detail previously [26]. All measurements reflecting disease activity remained more or less stable over the following 3 yr. Also, the HAQ scores improved significantly, but had a less favourable course in women; this difference remained at all follow-ups. Function, as measured by walking velocity and SOFI tests, deteriorated slowly and was almost back to baseline values at the 3-yr follow-up (data not shown).

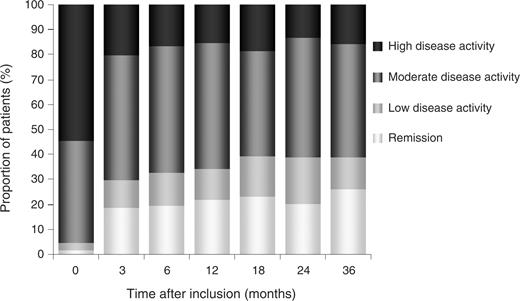

Almost 25% of the patients went into remission (DAS <2.6) but approximately 15% had a sustained high or moderate disease activity during all 3 yr (Fig. 1). The DAS-28 did not differ significantly between men and women at any time point.

Disease activity during the first 3 yr. Remission corresponds to DAS-28 <2.6, low disease activity to DAS-28 2.6–3.1, moderate disease activity to DAS-28 3.2–5.0, and high disease activity to DAS-28 ≥5.1.

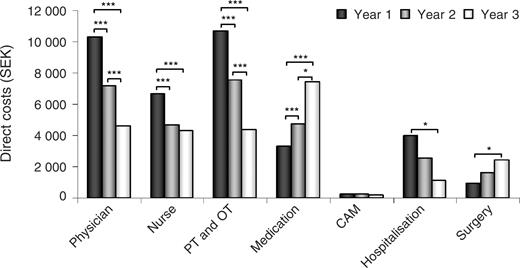

Direct costs over 3 yr

All direct costs were lowered over time, except for costs of drugs and surgery (Fig. 2). The average costs of ambulatory visits decreased substantially over the years, because visits were more frequent at the beginning of the disease. Costs for visits to the nurse, mainly to monitor the patient for possible side-effects of medication, were unchanged between years 2 and 3. The costs for hospitalization decreased between years 1 and 3 (P = 0.05). The average costs for surgery increased from year 1 to year 3 [SEK 706 (€ 76) vs SEK 2776 (€ 300); P = 0.037]. Women had higher costs for visits to a physician in year 1 (P = 0.002) and year 3 (P = 0.002), and to a physiotherapist and occupational therapist during year 2 (P = 0.02) compared with men. Women also had significantly higher usage of complementary care compared with men. The total costs were, however, quite low and rather few patients reported the use of complementary medicine (Table 3).

Costs (SEK) during the first 3 yr after diagnosis for the total group and for women and men separately

| . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . |

| . | (n = 276) . | (n = 254) . | (n = 195) . |

| Physician | |||

| Total | 10 036 (6399) | 7276 (6146) | 4512 (4469) |

| Women | 10 734 (7 031) | 7696 (5644) | 5024 (5041) |

| Men | 8543 (4455) | 6272 (7146) | 3360 (2451) |

| Nurse | |||

| Total | 6505 (2969) | 4680 (3488) | 4292 (2376) |

| Women | 6486 (2870) | 4912 (3962) | 4410 (2537) |

| Men | 6546 (3185) | 4125 (1839) | 4025 (1961) |

| PT and OT | |||

| Total | 9959 (9667) | 6928 (9650) | 4246 (2376) |

| Women | 10 383 (9105) | 7748 (10 297) | 4657 (8327) |

| Men | 9053 (10 770) | 4971 (7608) | 3322 (6641) |

| Medication | |||

| Total | 3189 (3629) | 4336 (6425) | 7199 (18 592) |

| Women | 3348 (3913) | 4571 (7095) | 7574 (19 599) |

| Men | 2849 (2922) | 3774 (4425) | 6356 (16 222) |

| CAM | |||

| Total | 292 (1108) | 239 (940) | 205 (1295) |

| Women | 388 (1312) | 319 (1105) | 280 (1548) |

| Men | 86 (343) | 47 (179) | 36 (156) |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Total | 3571 (15 924) | 2310 (11 586) | 1300 (6906) |

| Women | 4780 (18 780) | 2573 (12 898) | 581 (4190) |

| Men | 986 (5790) | 1680 (7633) | 2917 (10 634) |

| Surgery | |||

| Total | 706 (5383) | 1308 (6889) | 2776 (14 281) |

| Women | 839 (6210) | 1323 (7032) | 3776 (16 978) |

| Men | 421 (2933) | 1272 (6579) | 525 (2919) |

| Direct costs | |||

| Total | 34 258 (26 507) | 27 075 (26 159) | 24 592 (29 635) |

| Women | 36 959 (29 820) | 29 143 (28 853) | 26 302 (32 740) |

| Men | 28 486 (16 136) | 22 141 (17 380) | 20 540 (20 732) |

| Indirect costs | |||

| Total | 82 053 (128 994) | 78 989 (130 966) | 81 738 (136 090) |

| Women | 80 419 (125 293) | 76 633 (129 641) | 72 795 (124 378) |

| Men | 85 544 (129 002) | 84 614 (134 791) | 101 859 (158 644) |

| Total costs | |||

| Total | 116 311 (137 485) | 106 064 (137 366) | 106 267 (144 774) |

| Women | 117 379 (133 259) | 105 775 (136 007) | 99 097 (135 061) |

| Men | 114 030 (146 871) | 106 755 (141 489) | 122 400 (164 637) |

| . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . |

| . | (n = 276) . | (n = 254) . | (n = 195) . |

| Physician | |||

| Total | 10 036 (6399) | 7276 (6146) | 4512 (4469) |

| Women | 10 734 (7 031) | 7696 (5644) | 5024 (5041) |

| Men | 8543 (4455) | 6272 (7146) | 3360 (2451) |

| Nurse | |||

| Total | 6505 (2969) | 4680 (3488) | 4292 (2376) |

| Women | 6486 (2870) | 4912 (3962) | 4410 (2537) |

| Men | 6546 (3185) | 4125 (1839) | 4025 (1961) |

| PT and OT | |||

| Total | 9959 (9667) | 6928 (9650) | 4246 (2376) |

| Women | 10 383 (9105) | 7748 (10 297) | 4657 (8327) |

| Men | 9053 (10 770) | 4971 (7608) | 3322 (6641) |

| Medication | |||

| Total | 3189 (3629) | 4336 (6425) | 7199 (18 592) |

| Women | 3348 (3913) | 4571 (7095) | 7574 (19 599) |

| Men | 2849 (2922) | 3774 (4425) | 6356 (16 222) |

| CAM | |||

| Total | 292 (1108) | 239 (940) | 205 (1295) |

| Women | 388 (1312) | 319 (1105) | 280 (1548) |

| Men | 86 (343) | 47 (179) | 36 (156) |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Total | 3571 (15 924) | 2310 (11 586) | 1300 (6906) |

| Women | 4780 (18 780) | 2573 (12 898) | 581 (4190) |

| Men | 986 (5790) | 1680 (7633) | 2917 (10 634) |

| Surgery | |||

| Total | 706 (5383) | 1308 (6889) | 2776 (14 281) |

| Women | 839 (6210) | 1323 (7032) | 3776 (16 978) |

| Men | 421 (2933) | 1272 (6579) | 525 (2919) |

| Direct costs | |||

| Total | 34 258 (26 507) | 27 075 (26 159) | 24 592 (29 635) |

| Women | 36 959 (29 820) | 29 143 (28 853) | 26 302 (32 740) |

| Men | 28 486 (16 136) | 22 141 (17 380) | 20 540 (20 732) |

| Indirect costs | |||

| Total | 82 053 (128 994) | 78 989 (130 966) | 81 738 (136 090) |

| Women | 80 419 (125 293) | 76 633 (129 641) | 72 795 (124 378) |

| Men | 85 544 (129 002) | 84 614 (134 791) | 101 859 (158 644) |

| Total costs | |||

| Total | 116 311 (137 485) | 106 064 (137 366) | 106 267 (144 774) |

| Women | 117 379 (133 259) | 105 775 (136 007) | 99 097 (135 061) |

| Men | 114 030 (146 871) | 106 755 (141 489) | 122 400 (164 637) |

PT, physiotherapist; OT, occupational therapist; CAM, complementary medicine. SEK 1 = € 0.11 = US$ 0.1.

Costs (SEK) during the first 3 yr after diagnosis for the total group and for women and men separately

| . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . |

| . | (n = 276) . | (n = 254) . | (n = 195) . |

| Physician | |||

| Total | 10 036 (6399) | 7276 (6146) | 4512 (4469) |

| Women | 10 734 (7 031) | 7696 (5644) | 5024 (5041) |

| Men | 8543 (4455) | 6272 (7146) | 3360 (2451) |

| Nurse | |||

| Total | 6505 (2969) | 4680 (3488) | 4292 (2376) |

| Women | 6486 (2870) | 4912 (3962) | 4410 (2537) |

| Men | 6546 (3185) | 4125 (1839) | 4025 (1961) |

| PT and OT | |||

| Total | 9959 (9667) | 6928 (9650) | 4246 (2376) |

| Women | 10 383 (9105) | 7748 (10 297) | 4657 (8327) |

| Men | 9053 (10 770) | 4971 (7608) | 3322 (6641) |

| Medication | |||

| Total | 3189 (3629) | 4336 (6425) | 7199 (18 592) |

| Women | 3348 (3913) | 4571 (7095) | 7574 (19 599) |

| Men | 2849 (2922) | 3774 (4425) | 6356 (16 222) |

| CAM | |||

| Total | 292 (1108) | 239 (940) | 205 (1295) |

| Women | 388 (1312) | 319 (1105) | 280 (1548) |

| Men | 86 (343) | 47 (179) | 36 (156) |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Total | 3571 (15 924) | 2310 (11 586) | 1300 (6906) |

| Women | 4780 (18 780) | 2573 (12 898) | 581 (4190) |

| Men | 986 (5790) | 1680 (7633) | 2917 (10 634) |

| Surgery | |||

| Total | 706 (5383) | 1308 (6889) | 2776 (14 281) |

| Women | 839 (6210) | 1323 (7032) | 3776 (16 978) |

| Men | 421 (2933) | 1272 (6579) | 525 (2919) |

| Direct costs | |||

| Total | 34 258 (26 507) | 27 075 (26 159) | 24 592 (29 635) |

| Women | 36 959 (29 820) | 29 143 (28 853) | 26 302 (32 740) |

| Men | 28 486 (16 136) | 22 141 (17 380) | 20 540 (20 732) |

| Indirect costs | |||

| Total | 82 053 (128 994) | 78 989 (130 966) | 81 738 (136 090) |

| Women | 80 419 (125 293) | 76 633 (129 641) | 72 795 (124 378) |

| Men | 85 544 (129 002) | 84 614 (134 791) | 101 859 (158 644) |

| Total costs | |||

| Total | 116 311 (137 485) | 106 064 (137 366) | 106 267 (144 774) |

| Women | 117 379 (133 259) | 105 775 (136 007) | 99 097 (135 061) |

| Men | 114 030 (146 871) | 106 755 (141 489) | 122 400 (164 637) |

| . | Year 1 . | Year 2 . | Year 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . | Mean (s.d.) . |

| . | (n = 276) . | (n = 254) . | (n = 195) . |

| Physician | |||

| Total | 10 036 (6399) | 7276 (6146) | 4512 (4469) |

| Women | 10 734 (7 031) | 7696 (5644) | 5024 (5041) |

| Men | 8543 (4455) | 6272 (7146) | 3360 (2451) |

| Nurse | |||

| Total | 6505 (2969) | 4680 (3488) | 4292 (2376) |

| Women | 6486 (2870) | 4912 (3962) | 4410 (2537) |

| Men | 6546 (3185) | 4125 (1839) | 4025 (1961) |

| PT and OT | |||

| Total | 9959 (9667) | 6928 (9650) | 4246 (2376) |

| Women | 10 383 (9105) | 7748 (10 297) | 4657 (8327) |

| Men | 9053 (10 770) | 4971 (7608) | 3322 (6641) |

| Medication | |||

| Total | 3189 (3629) | 4336 (6425) | 7199 (18 592) |

| Women | 3348 (3913) | 4571 (7095) | 7574 (19 599) |

| Men | 2849 (2922) | 3774 (4425) | 6356 (16 222) |

| CAM | |||

| Total | 292 (1108) | 239 (940) | 205 (1295) |

| Women | 388 (1312) | 319 (1105) | 280 (1548) |

| Men | 86 (343) | 47 (179) | 36 (156) |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Total | 3571 (15 924) | 2310 (11 586) | 1300 (6906) |

| Women | 4780 (18 780) | 2573 (12 898) | 581 (4190) |

| Men | 986 (5790) | 1680 (7633) | 2917 (10 634) |

| Surgery | |||

| Total | 706 (5383) | 1308 (6889) | 2776 (14 281) |

| Women | 839 (6210) | 1323 (7032) | 3776 (16 978) |

| Men | 421 (2933) | 1272 (6579) | 525 (2919) |

| Direct costs | |||

| Total | 34 258 (26 507) | 27 075 (26 159) | 24 592 (29 635) |

| Women | 36 959 (29 820) | 29 143 (28 853) | 26 302 (32 740) |

| Men | 28 486 (16 136) | 22 141 (17 380) | 20 540 (20 732) |

| Indirect costs | |||

| Total | 82 053 (128 994) | 78 989 (130 966) | 81 738 (136 090) |

| Women | 80 419 (125 293) | 76 633 (129 641) | 72 795 (124 378) |

| Men | 85 544 (129 002) | 84 614 (134 791) | 101 859 (158 644) |

| Total costs | |||

| Total | 116 311 (137 485) | 106 064 (137 366) | 106 267 (144 774) |

| Women | 117 379 (133 259) | 105 775 (136 007) | 99 097 (135 061) |

| Men | 114 030 (146 871) | 106 755 (141 489) | 122 400 (164 637) |

PT, physiotherapist; OT, occupational therapist; CAM, complementary medicine. SEK 1 = € 0.11 = US$ 0.1.

Direct costs over 3 yr and changes between years. CAM, complementary medicine; PT, physiotherapist; OT, occupational therapist. ***P<0.001; **P<0.01; *P<0.05. SEK 1 = € 0.11 = US$ 0.1.

During the first year, 21 patients (8%) were admitted to hospital and in year 3 the number dropped to nine patients (5%). One total hip arthroplasty was performed in the first year and one total knee arthroplasty in the second year. During the third year, five total joint replacements were done. The remaining operations were hand and/or foot surgeries (Table 4).

Annual utilization of hospitalization and surgery

| . | Hospitalization . | . | Surgeries . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Women . | Men . | Mean (range) no. of days in hospital . | Number of surgeries . | Women . | Men . | ||||

| Year 1 (n = 276) | 17 | 4 | 17 (1–43) | 10 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Year 2 (n = 254) | 12 | 7 | 12 (1–38) | 16 | 10 | 4 | ||||

| Year 3 (n = 195) | 4 | 5 | 11 (1–28) | 19 | 13 | 2 | ||||

| . | Hospitalization . | . | Surgeries . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Women . | Men . | Mean (range) no. of days in hospital . | Number of surgeries . | Women . | Men . | ||||

| Year 1 (n = 276) | 17 | 4 | 17 (1–43) | 10 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Year 2 (n = 254) | 12 | 7 | 12 (1–38) | 16 | 10 | 4 | ||||

| Year 3 (n = 195) | 4 | 5 | 11 (1–28) | 19 | 13 | 2 | ||||

Annual utilization of hospitalization and surgery

| . | Hospitalization . | . | Surgeries . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Women . | Men . | Mean (range) no. of days in hospital . | Number of surgeries . | Women . | Men . | ||||

| Year 1 (n = 276) | 17 | 4 | 17 (1–43) | 10 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Year 2 (n = 254) | 12 | 7 | 12 (1–38) | 16 | 10 | 4 | ||||

| Year 3 (n = 195) | 4 | 5 | 11 (1–28) | 19 | 13 | 2 | ||||

| . | Hospitalization . | . | Surgeries . | . | . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Women . | Men . | Mean (range) no. of days in hospital . | Number of surgeries . | Women . | Men . | ||||

| Year 1 (n = 276) | 17 | 4 | 17 (1–43) | 10 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Year 2 (n = 254) | 12 | 7 | 12 (1–38) | 16 | 10 | 4 | ||||

| Year 3 (n = 195) | 4 | 5 | 11 (1–28) | 19 | 13 | 2 | ||||

The age group 40–59 had higher direct costs compared with the remaining groups and men ≥65 had lower costs compared with younger men and compared with all women. No correlation was found between educational level, marital status and direct costs.

Total direct costs were higher for women compared with men during the first 2 yr (P = 0.001). When adjustment was made for age, the costs were higher for women in year 1 but not in year 2 and there was no significant difference in year 3. Direct costs decreased from year 1 to year 3 (P<0.0001). The mean annual direct cost per patient was SEK 34 258 (€ 3704) in the first year, SEK 27 075 (€ 2927) in the second year and SEK 24 592 (€ 2652) in the third year (Table 3).

Biological pharmacotherapy

Biological pharmacotherapy, i.e. targeted TNF inhibition, was introduced at the end of year 2, thus increasing average drug costs substantially [SEK 3189 (€ 345) in year 1 vs SEK 7199 (€ 778) in year; P = 0.002]. The increase in drug costs between year 1 and year 3 was more pronounced in women than in men (P = 0.009) (Table 3). Fourteen patients (5%) were prescribed biological therapy after a disease duration of approximately 3 yr. They had all previously been treated with methotrexate and different DMARD combinations. The mean cost during the third year for the patients with TNF-inhibitors was SEK 70 800 (€ 7654) compared with SEK 4078 (€ 441) for patients not treated with biologicals (P<0.0001). The total direct and indirect costs were, however, higher for the future TNF-inhibitor group, even before the start of anti-TNF treatment.

Indirect costs over 3 yr

The mean annual indirect costs were SEK 82 053 (€ 8871) in the first year, SEK 78 989 (€ 8539) in the second year and SEK 81 738 (€ 8837) in the third year (Table 3). While direct costs decreased, indirect costs were mainly unchanged. This pattern was similar for both women and men. Men had higher indirect costs in year 3 compared with women, but this difference was not significant (P = 0.8).

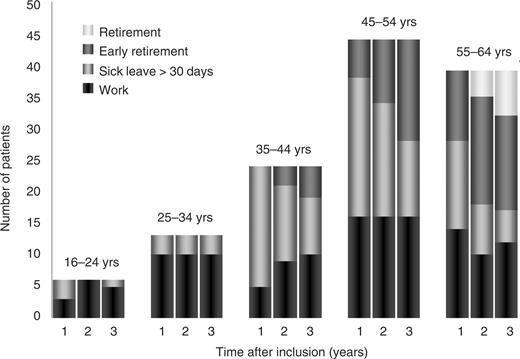

The employment rate remained mainly unchanged during the first 3 yr compared with baseline data. At inclusion, younger patients were employed to a greater extent than older patients. Approximately 80% of the patients below 35 yr of age were working, compared with 40% in the group ≥35. This pattern persisted over time. In the 35- to 44-yr group there was a slight increase in working capacity. In general, costs for sick leave decreased, but this was offset by increasing costs of early retirement, due to permanent work disability (Fig. 3). Indirect costs were higher for those with a low educational level. When controlling for age, however, the differences disappeared since educational level was strongly dependent on age. Indirect costs exceeded direct costs by a factor of 2.4 during the first year, by a factor of 2.9 in the second year and a factor of 3.3 in the third year.

Change in employment rate, sick leave and early retirement over the first 3 yr in patients aged 65 yr with complete data for all 3 years (n = 126).

Discussion

Cost-of-illness studies cannot evaluate consequences for the individual patient but can estimate costs for a group of patients, which could be valuable for decision-makers in allocating health-care resources. It can also be used as a basis for decisions concerning treatment and future research strategies [33].

We have calculated total costs for an inception cohort of patients with recent-onset RA. Substantial costs were incurred already from the beginning. Total costs are probably underestimated since non-medical costs were not included in the calculation of direct costs, and since only paid work was valued when loss of productivity was calculated. The disease activity had decreased significantly already 3 months after inclusion and remained rather unchanged during the following 3 yr. Function tended to deteriorate after an initial improvement. The mean changes were, however, rather small and may not denote an important clinical difference. The HAQ scores were more consistent and showed a sustained improvement. The scores were similar for men and women at baseline but had a less favourable course for women, and this significant difference between women and men remained over time. About 15% of the patients had persistently moderate or high disease activity despite medication.

Educational level is a good surrogate measure of socio-economic status and has been recognized as a predictor of costs [34]. We failed to show this association, probably because the mean age of our cohort was >56 yr. This affected the formal level of education, since older patients had a lower educational level.

Comorbidity has also been associated with higher costs [12, 35]. Thirty-three per cent of our patients reported comorbidity, but we did not find any significant associations with costs.

Verstappen et al. [36] reported that direct costs were high in the first years after diagnosis, slightly lower thereafter and then increased with disease duration. This is in accordance with the present study, where the costs were highest in the first year, reflecting the more frequent visits of the patients in the early phase of the disease. All patients followed a study protocol, which initially resulted in many ambulatory care visits. The number of physician visits, however, did not differ substantially from the ordinary follow-up routines but the number of physiotherapist and occupational therapist visits was higher in the first year compared with previous clinical routines. One of the main aims of the TIRA project was, however, to implement an early multiprofessional intervention for patients with early RA. This is now standard procedure at the participating TIRA units.

The higher costs for women and higher HAQ scores indicated a more severe disease course in women. This impression was supported by the fact that women also underwent more surgery than did men. The medication costs were predominantly driven by the introduction of biological pharmacotherapy and, to some extent, by frequent therapeutic monitoring and adverse effects. The costs for surgery increased due to the increasing number of operations and more major surgery, such as total hip and knee replacements. The average usage of complementary medicine was rather low and this type of medicine was used only by a few patients. The usage was greatest at the beginning of the disease and then decreased gradually. This might indicate that patients tried different alternative medications early after diagnosis, but lost faith in such medication in the years to follow.

The present study was carried out at the time when TNF-α blockers were being introduced for the treatment of therapy-resistant RA. Only 14 patients received biological pharmacotherapy. The small sample size may possibly have given significant results by chance, and we are therefore cautious concerning conclusions. In recent cost–effectiveness studies, Kobelt et al. [37, 38] showed that treatment with anti-TNF-α inhibitors reduced direct and indirect costs, thus partly offsetting the increased costs. Also the ratios of cost-effectiveness ratios were within acceptable ranges for treatment. More rapid control of disease activity may very well have a potential to lower indirect costs and to some extent offset costs. Quinn et al. [39] recently reported that very early treatment with anti-TNF-α provided a sustained response to therapy 1 yr after stopping the medication and a partial response even 2 yr afterwards. Previously, drugs represented a minor cost—about 10–15% of the direct costs. The introduction of the biological agents has considerably changed the distribution of costs. In the present study, drugs accounted for 9% of direct costs in the first year and almost 30% in the third year.

Work disability made up the largest cost of RA and exceeded by far the costs of treatment. At inclusion, more than half of the patients below 65 yr of age were already on sick-leave or had retired early. The costs for sick leave were lowered, but this was offset by increasing costs for early retirement. Eighteen patients had already retired early at inclusion, possibly due to diseases other than arthritis. This might lead to overestimation of early retirement due to RA. Indirect costs were calculated using a human capital approach. This might overestimate indirect costs in a society with a high unemployment rate.

There are some limitations in the study. Cost estimates were based upon self-reported data, where recall bias cannot be ruled out. This was especially obvious during year 3, where only one questionnaire was used and patients thus had to report health-care utilization and days lost from work during the previous 12 months. The questionnaires were, however, distributed at the preceding visit and were thus available during the whole period to be filled in gradually by the patients. In general, the questionnaires were very detailed concerning medication, dosage and amount, as well as hospitalization and surgery. The number of out-patient visits tended, however, to be underreported (compared with the known visits according to the study protocol and the drug monitoring protocol). This is in accordance with Ruof et al. [40], who compared self-reports with the payer's source and found a high level of accuracy concerning medication and in-patient care, while physician visits and diagnostic tests were underreported. Loss of productivity also includes the value of lost production due to premature death caused by the disease. This was not taken into account in the present study. The intangible costs resulting from pain, fatigue and loss-of-efficacy are considerable for patients and their families. These data were, however, difficult to calculate and were therefore omitted from the present study.

Longitudinal studies, compared with cross-sectional studies, can capture the entire effect of long-term illness. Compiling data from a longitudinal prospective study, with patients from different regions and participating hospitals of different sizes, eliminates possible bias with patient selection, and this is a strength of the present study.

To conclude, highly significant improvements were seen 3 months after the diagnosis of patients with recent-onset (<12 months) RA, but approximately 15% of the patients had sustained high disease activity in all 3 yr. All direct costs were lowered, except costs for medication and surgery, which were significantly increased, and this was more pronounced in women. Women had more ambulatory care visits and used complementary medicine to a greater extent than did men. Patients who were eventually prescribed TNF inhibitors incurred higher direct and indirect costs even before prescription of anti-TNF therapy. The present study was conducted during a period of shifting paradigms and the introduction of efficacious new treatment modalities. Future prospective studies will be carried out in a new cohort of recent-onset RA, using this historic TIRA cohort as an invaluable reference.

We thank Ylva Billing and all TIRA partners at the rheumatology units in Eskilstuna, Jönköping, Kalmar, Lindesberg, Linköping, Motala, Norrköping, Oskarshamn, Västervik and Örebro for excellent cooperation. Grant support was received from The Medical Research County Council of South-East Sweden (FORSS), The Swedish Rheumatism Association, The Swedish Research Council (project K2003-74VX-14594-01A), King Gustaf V 80-year Foundation and The National Board of Health and Welfare.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Pincus T, Callahan LF, Sale WG, Brooks AL, Payne LE, Vaughn WK. Severe functional declines, work disability, and increased mortality in seventy-five rheumatoid arthritis patients studied over nine years.

Sherrer YS, Bloch DA, Mitchell DM, Young DY, Fries JF. The development of disability in rheumatoid arthritis.

Rasker JJ, Cosh JA. The natural history of rheumatoid arthritis over 20 years. Clinical symptoms, radiological signs, treatment, mortality and prognostic significance of early features.

Sokka T, Krishnan E, Häkkinen A, Hannonen P. Functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients compared with a community population in Finland.

Pugner KM, Scott DI, Holmes JW, Hieke K. The costs of rheumatoid arthritis: an international lomg-term view.

Lapsley HM, March LM, Tribe KL, Cross MJ, Courtenay BG, Brooks PM. Living with rheumatoid arthritis: expenditures, health status, and social impact on patients.

Wong JB, Ramey DR, Singh G. Long-term morbidity, mortality, and economics of rheumatoid arthritis.

Merkesdal S, Ruof J, Schöffski O, Bernitt K, Zeidler H, Mau W. Indirect medical costs in early rheumatoid arthritis: composition of and changes in indirect costs within the first three years of disease.

Kobelt G, Eberhardt K, Jonsson L, Jonsson B. Economic consequences of the progression of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden.

Meenan RF, Yelin EH, Henke CJ, Curtis DL, Epstein WV. The costs of rheumatoid arthritis: a patient-oriented study of chronic disease costs.

Yelin E. The costs of rheumatoid arthritis – absolute, incremental and marginal estimates.

Leardini G, Salaffi F, Montanelli R, Gerzeli S, Canesi B. A multicenter cost-of-illness study on rheumatoid arthritis in Italy.

Larsson SE, Jonsson B, Palmefors L. Joint disorders and walking disability in Sweden by the year 2000. Epidemiologic studies of a Swedish community.

Simonsson M, Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, Svensson B. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden.

Jonsson D, Husberg M. Socioeconomic costs of rheumatic diseases: implications for technology assessment.

Schmidt A, Husberg M, Bernfort L. Samhällsekonomiska kostnader för reumatiska sjukdomar. CMT Rapport 2003:5. Linköping: Centre for Medical Technology Assessment, Linköping University, Sweden [in Swedish].

Hallert E, Husberg M, Jonsson D, Skogh T. Rheumatoid arthritis is already expensive during the first year of the disease (the Swedish TIRA Project).

Kalden JR. Expanding role of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis.

Yelin E, Wanke L. An assessment of the annual and long-term direct costs of rheumatoid arthritis.

Lubeck DP, Spitz PW, Fries JF, Wolfe F, Mitchell DM, Roth SH. A multicenter study of annual health service utilization and costs in rheumatoid arthritis.

Clarke AE, Levinton C, Joseph L et al. Predicting the short term direct medical costs incurred by patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Emery P. Evidence supporting the benefit of early intervention in rheumatoid arthritis.

Scott DL. Pursuit of optimal outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis.

Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I et al. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies.

Poulakka K, Kautiainen H, Mottonen T et al. Early suppression of disease activity is essential for maintenance of work capacity in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis.

Hallert E, Thyberg I, Hass U, Skargren E, Skogh T. Comparison between women and men with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis regarding disease activity and functional ability over two years (the TIRA project).

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Blich DA et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis.

Prevoo MLL, van't Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LBA, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts.

Eberhardt KB, Svensson B, Moritz U. Functional assessment of early rheumatoid arthritis.

Fries J, Spitz P, Kraines R, Holman H. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis.

Federation of Swedish County Councils (Landstingsförbundet). Stockholm. www.lf.se

Serden L, Lindquist R, Rosen M. Have DRG-based prospective payment systems influenced the number of secondary diagnoses in health care administrative data?

Emery P. Review of health economics modelling in rheumatoid arthritis.

Poulakka K, Kautiainen H, Mottonen T et al. Predictors of productivity loss in early rheumatoid arthritis: a 5 year follow up study.

Michaud K, Messer J, Choi HK, Wolfe F. Direct medical costs and their predictors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Verstappen SM, Verkleij H, Bijlsma JW et al. Determinants of direct costs in Dutch rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Kobelt G, Jonsson L, Young A, Eberhardt K. The cost-effectiveness of infliximab (Remicade) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden and the United Kingdom based on the ATTRACT study.

Kobelt G, Lindgren P, Singh A, Klareskog L. Cost-effectiveness of etanercept (Enbrel) in combination with methotrexate in the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis based on the TEMPO trial.

Quinn MA, Conaghan PG, O’Connor PJ et al. Very early treatment with infliximab in addition to methotrexate in early poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis reduces magnetic resonance imaging evidence of synovitis and damage, with sustained benefit after infliximab withdrawal.

Author notes

1Division of Rheumatology/AIR, Department of Molecular and Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping University Hospital and 2Centre for Medical Technology Assessment, Department of Health and Society, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden.

Comments