Opinion is divided on who should follow up patients leaving secure care. Reference Chaloner and CoffeyChaloner & Coffey (2000) believe that community supervision of such patients requires sensitive handling, a sound knowledge of mental health law and a firm understanding of risk management. They also suggest that the word ‘forensic’ causes controversy among mental health professionals outside of secure care, who often see ‘the forensic patient’ as dangerous.

History of community forensic psychiatry

The need for medium secure psychiatric provision across England and Wales was identified almost 40 years ago, in the Glancy (Department of Health and Social Services 1974) and Butler (Home Office 1975) reports. This was at much the same time as the growth in the idea of ‘care in the community’, with the closure of the old Victorian-style psychiatric institutions and the introduction of community psychiatric provision. The Reed Report (Reference ReedReed 1992) followed, suggesting a number of principles that are still adhered to across secure psychiatric services. These include:

-

• treating patients in the minimum level of security (which could be in the community)

-

• basing care on individual need

-

• diverting mentally ill offenders out of the criminal justice system and into healthcare

-

• better multiprofessional working and improved risk assessment

-

• maximising rehabilitation, with the prospect of independent living.

In 1994, the Maudsley Hospital in London established a forensic outreach service, utilising an integrated approach and collaborative working – ‘liaison, consultation and provision of support to psychiatric teams as they manage their patients’ (Reference Whittle and ScallyWhittle 1998). In many other parts of the country, both in-patient and community services for mentally disordered offenders and those requiring similar care were initially slow to develop. However, over the past decade there has been a significant expansion across a range of forensic services, including services for women, children and individuals with personality disorder. Community care has been enhanced by the introduction of functionalised teams (e.g. assertive outreach, early intervention, crisis resolution and home treatment). Reference Pelosi and BirchwoodPelosi & Birchwood (2003), in debating the need and usefulness of functionalisation, note that the balance should be dependent on the needs of the local community.

Reference Coid, Kahtan and GaultCoid and colleagues (2001) have suggested that the development of current forensic aftercare services was based on poor local aftercare provision in the 1970s, following the closure of large psychiatric hospitals. In a comparison of seven medium secure services in England and Wales, they found that these differed on a range of criteria. They felt that service development had been uncoordinated and that there was no consistency in the management of the patient’s move from secure care back into the community.

A comparison of outcomes of aftercare provided by forensic and by general adult psychiatric services following discharge from medium security (Reference Coid, Hickey and YangCoid 2007) revealed that:

-

• forensic services supervised fewer high-risk patients than did general psychiatric services;

-

• neither service was superior in outcome;

-

• there was no difference in readmission rates;

-

• if readmission did occur, individuals who had been followed up by local services usually went to local psychiatric hospitals, but those followed up by forensic services usually went back to medium security;

-

• there was no difference in terms of criminal reconvictions and type of offence, except for a slight variance in the rate of violence.

The needs of the patient

The demands of a ‘forensic’ mental health population are different from those of a general mental health population. In our experience, forensic patients are generally stable but are more likely to pose significant risk (compared with general adult patients) should they have a relapse of their illness. If it were not for the risks posed by a relapse of symptoms, it is likely that they would not be followed up by forensic community services (Reference SzmuklerSzmukler 2002).

The building of good relationships based on trust is particularly important in caring for ‘forensic’ patients. There should be as little disruption as possible to continuity of care, because therapeutic relationships are essential to maintaining these patients in the community, especially in relation to treatment adherence (Reference McClelland, Humphreys and ConlonMcClelland 2001). A trusting relationship takes time to develop, especially in forensic populations, and rehabilitation should begin soon after admission (Reference Lindqvist and SkipworthLindqvist 2000).

Approaches to aftercare

Reference Mohan, Slade and FahyMohan et al (2004) have described three service models for the follow-up of patients discharged from medium secure care: parallel, integrated and hybrid (Box 1).

BOX 1 Models of care for mentally disordered offenders on discharge from medium secure units

Parallel Forensic services that use this model provide both the in-patient and community components of the patient’s care. Readmission would be to the medium secure unit and the forensic team would expect to provide a full long-term community service to patients under their care.

Integrated In this model, medium secure units provide in-patient treatment and once the need for such security has ended, general adult services take over the longer-term treatment/rehabilitation and integrate the patient into their services. Readmission, if necessary, would be to a local general psychiatric hospital.

Hybrid This model runs integrated services but uses ‘shared care’ in the critical period following discharge, with forensic services retaining long-term responsibility for the ‘critical few’ who are considered to be high-risk offenders, such as those on restriction orders. If readmission is necessary, it will usually be to a local general psychiatric hospital; in certain circumstances the patient will return to the medium secure unit (particularly in the case of the ‘critical few’).

(Reference GunnGunn 1997; Reference McKenna and JasperMcKenna 1999; Reference Snowden, McKenna and JasperSnowden 1999; Reference Mohan, Slade and FahyMohan 2004)

Forensic community team

Reference OzduralOzdural (2006) proposes forensic community teams as the ideal solution to caring for those in transition from medium security to the community. The community forensic mental health team plays an important role in surveillance, with a proactive response if circumstances change to increase risk. Reference Judge, Harty and FahyJudge and colleagues (2004) surveyed all 37 community forensic mental health teams in England and Wales at the time; they found that most operated in parallel with adult mental health services. All teams were concerned with risk assessment and management and very few had developed treatments to reduce offending behaviour. The authors found support for the development of a parallel community forensic service, but felt that more research was required to evaluate such services.

Reference Buchanan and BuchananBuchanan (2002) concludes that risk is the criterion most often used for the development of parallel services. He contends that the selection of mentally disordered offenders for forensic community services is more likely to be based on clinical needs that have been defined locally. The guiding principle for referral should be that the risk posed to others (because of the individual’s mental disorder) can only be met by a specialist forensic community mental health team. Buchanan describes these needs in terms of clinical backgrounds that require greater ongoing observation and monitoring than the norm (i.e. increased risk of harm to self and others when unwell requires more frequent visits, resources such as day centres to structure the individual’s day, etc.). Buchanan suggests that when a critical mass of such individuals is identified, the stretching effect on general adult services is profound, necessitating the setting up of specialist services. However, he states that even with a specialist service, there should be some integration with general services, rather than a full parallel service. He notes that the main strength of the parallel model is that it best minimises the risk of future serious offending by patients with a significant history of offending associated with psychiatric illness. It is unlikely that a busy community mental health team would be able to supervise such patients in the community with the same degree of risk minimisation.

Reference Turner and SalterTurner & Salter (2005, Reference Turner and Salter2008) have argued for a re-integration of services, believing that ‘high-risk’ patients – those thought likely to pose a high risk to others – should not solely be the reserve of forensic psychiatrists. They debate the disbanding of the specialty of ‘forensic psychiatry’ and the reallocation of its resources to the majority (local mental health teams).

In a discussion of models of community care provision for mentally disordered offenders, Reference Tighe, Henderson, Thornicroft and BuchananTighe and colleagues (2002) cited only six papers from peer-reviewed journals between 1977 and 1999. In the main, the debate was whether teams should be parallel, hybrid or integrated into general teams. They concluded that, rather than being mutually exclusive, these models sit on a continuum and the model chosen should depend on the demographics of the population being considered. In discussing the practical application of roles for each type of service, they stress that the integrity of practitioners can be maintained in both parallel and integrated services by having explicit lines of accountability.

Current provision

Reference Holloway and BuchananHolloway (2002) has described four current models of community support for mentally disordered offenders in England and Wales:

-

• a generic community mental health team manages these individuals; according to Holloway, most mentally disordered offenders fit into this category;

-

• specialist forensic practitioners work together with general adult staff to provide a service through a consultation/liaison approach;

-

• a separate specialist community forensic mental health team supports the individuals;

-

• individuals who pose a risk to others receive outreach support from the forensic responsible clinician in a hospital setting.

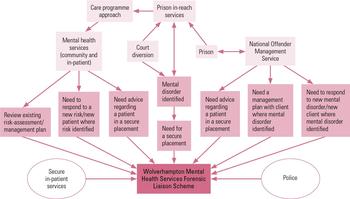

Holloway concludes that managing the complex presentation of mentally disordered offenders in the community requires specialist support, resources and training. In areas with a substantial forensic mental health population, specialist forensic community mental health teams should be in place along the secure care pathway (Fig. 1). From work done by the Royal College of Psychiatrists’s Quality Network for Forensic Mental Health Services (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/quality/qualityandaccreditation/forensic/forensicmentalhealth.aspx), it is clear that these would be necessary to support the regional medium secure units and local low secure locked wards. In rural settings, the model to be considered should be a slimmed down forensic community mental health team with closer links to general adult services and supervision by a senior forensic mental health clinician.

FIG 1 Secure care pathways and existing discharge/diversion pathways.

Community forensic psychiatry in other countries

Reference Gordon and LindqvistGordon & Lindqvist (2007) note that a parallel model of care is followed in Germany; in other western European countries, a mixture of parallel and integrated care is adopted. Community services in eastern European countries are limited. The primary factors that influence the development of community services in different countries are their legal framework and history. In contrast to the various models in different states in the USA, the UK’s integration of health and social care has played an important role in shaping the function and operation of community services. The White Paper Caring for People (Department of Health 1989) encouraged the development of locally based services and collaboration between the health, social and voluntary or third sectors, advocating the need for proper coordination to avoid fragmentation of care.

The liaison way of working

The liaison model of service delivery is different from standard community forensic mental health team provision. There is little evidence of the efficacy of the forensic mental health liaison model, such services are developing ad hoc and there is no Department of Health direction on them. However, over the past two decades, the liaison ‘way of working’ has become ubiquitous in the National Health Service (NHS) and liaison services aspire to provide advice, education, support, training and expertise.

Several factors are key to the success of an effective liaison model (Box 2). Primarily, there must be sufficient resources, and commitment at the service and commissioning levels. There must also be sufficient expertise within the liaison team. The team should be easily accessible, willing and able to work collaboratively and broaden their knowledge. All members of the team should work to a referral threshold that avoids overspecification of referral criteria. The liaison model works specifically by supporting and advising clinicians who work daily with mentally disordered offenders. The liaison model allows early intervention – before an individual’s risk increases or before re-offending occurs. Importantly, the responsible clinician role remains with the general adult service, engendering continuity of care. As a result, the liaison services can oversee a high caseload without retaining direct responsibility for patient care (Box 3).

BOX 2 Some principles of the liaison model

-

• Shared care

-

• Low threshold for referral

-

• Early intervention

-

• Good collaborative risk management

-

• Good communication between services

BOX 3 Advantages of working in a liaison model

-

• Continuity of care for mentally disordered offenders between mental health services (both tertiary and secondary) and the criminal justice system, facilitating good multi-agency working

-

• Rapid access to expert advice regarding risk assessment and management

-

• Oversight of secure admissions to allow for appropriate admissions and timely discharge

-

• Good productive working relationships between forensic and local services through partnership working and improved communication

-

• Ensures local accountability and involvement by empowering local clinicians in complex case management, with significant increases in confidence and competence of local service staff in risk assessment and management

-

• An overall achievement of health and economic benefits through service integration/alignment

The liaison model in Wolverhampton

The Wolverhampton Mental Health Services Forensic Liaison Scheme (WMHSFLS) was set up by a group of interested clinicians in 1997. Within the West Midlands, there was dissatisfaction among commissioners and service providers (of both forensic and general adult mental health services) about the poor communication structures and clinical care pathways for patients at the interface of these services. There was also a significant number of Wolverhampton patients placed ‘out of area’ in secure independent-sector units who required continuity of care from local services. In 1997, the Hatherton Centre (a medium secure unit in Stafford) was approached to ascertain what interest they had in developing innovative and effective ways of working with adult mental health services in Wolverhampton (population 250 000). The clinicians and managers who were involved considered different approaches to caring for mentally disordered offenders and those individuals with similar needs. This led to the beginnings of the liaison model of care between the two services.

The liaison service was initially funded by the Mentally Disordered Offenders Strategic Assistance Fund. Since it was granted Beacon status (a government award for models of excellence), the service has been fully funded. It is worth noting that the Wolverhampton scheme is run as a true partnership between the Forensic Mental Health Services Directorate of South Staffordshire and Shropshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and Wolverhampton City Primary Care Trust’s Adult Mental Health Services. It can, however, sometimes be a challenge to work within such different organisations with competing priorities.

The Wolverhampton scheme includes clinicians from the medium secure service in Stafford and the adult mental health services in Wolverhampton. The clinicians from the forensic service are also members of a multiprofessional clinical team at the Hatherton Centre with responsibility for the care of in-patients from Wolverhampton. The forensic service provides weekly sessions by a consultant forensic psychiatrist and a consultant forensic nurse, who are joint leads. A consultant forensic clinical psychologist provides two sessions a week (one for the scheme and one for direct treatment); a senior practitioner (social work) and senior forensic nurse complete the forensic service’s side of the team. On Wolverhampton adult mental health services side, a senior nurse acts as coordinator, and there are three community mental health nurses attached to the three community mental health teams in Wolverhampton. Each of the three community mental health nurses holds the ‘forensic’ caseload for their respective team and the coordinator provides managerial supervision and leadership for these clinicians. The forensic consultant nurse provides regular clinical supervision to the scheme coordinator. One of the community mental health nurses is a Black and minority ethnic (BME) worker, recruited to the post to work with patients of African–Caribbean ethnicity. This nurse is formally linked to a voluntary service (African Caribbean Community Initiative, ACCI) that provides day services and accommodation for African–Caribbean individuals who have mental health problems. The members of the scheme work together as a single multiprofessional clinical team and meet weekly. The scheme has a distinct operational policy that has been developed and agreed by clinicians and managers from both trusts. This policy includes referral and discharge criteria and describes the activities and governance arrangements for the Wolverhampton scheme (Box 4).

BOX 4 The overall aims of the Wolverhampton Mental Health Services Forensic Liaison Scheme

-

1 To promote well-informed, effective and rewarding working relationships

-

2 To ensure that the limited resources available are used to maximum advantage

-

3 To ensure effective clinical consultation and liaison over patient care

-

4 To ensure dissemination of clinical information according to the principles and practices of the care programme approach

-

5 To facilitate effective early involvement of forensic services and increase the effectiveness of risk management plans

-

6 To coordinate the care of mentally disordered offenders from Wolverhampton, irrespective of their location

-

7 To facilitate mutual learning between the two services

-

8 To disseminate the liaison scheme model locally and nationally

The emphasis is on patients being ‘owned’ by their local mental health service provider, with clinical responsibility being maintained by the appropriate local team unless the individual is admitted to secure care as an in-patient. Contact with individuals is maintained through the Wolverhampton scheme wherever the individuals may be (e.g. prison, bail hostel, secure unit), to ensure that the clinical pathway is as seamless as possible and that the individual returns to local services as soon as is clinically appropriate. Effective multi-agency communication is an essential component of the scheme and there are excellent working relationships with other healthcare providers, criminal justice agencies and the voluntary sector (Box 5).

BOX 5 Activities of the Wolverhampton Mental Health Services Forensic Liaison Scheme

-

• A weekly review of patients referred to the scheme. All available members attend. Approximately 12 patients are reviewed each week

-

• Specialist assessments of patients referred to the scheme

-

• Regular visits to local prisons and other secure services (low, medium and high), including private sector establishments, to establish and maintain continuity of care

-

• Supervision (clinical and academic)

-

• Continuing professional development (CPD)

-

• Audit and research

-

• Liaison with other professional agencies and the voluntary sector

The forensic coordinator (based at Wolver-hampton City Primary Care Trust) also attends levels 2 and 3 Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangement (MAPPA) meetings and has developed effective communication systems with the agencies involved.

A similar scheme has been established by clinicians in Shropshire and a preliminary satisfaction survey among secondary services has indicated that it is a useful arrangement that provides helpful advice regarding risk assessment and management (C. Barkley, C. Davies, personal communication, 2009).

Referral process

All referrals are received by the forensic coordinator. The Wolverhampton scheme generally prioritises referrals and follow-up reviews on the basis of their urgency, status, time since referral and the appropriateness of the individual’s current placement (Box 6).

BOX 6 Factors considered when prioritising referrals

-

• Sudden deterioration in mental health

-

• Recent and unforeseen incidents suggestive of increased risk of harm to self and others

-

• Serious documented concerns from the team responsible for the individual

-

• Review request from the in-patient units at Wolverhampton (including the psychiatric intensive care unit)

-

• Referral from the Court Engagement and Liaison Scheme and diversion at the point of arrest schemes

-

• Referral from prisons/other hospitals

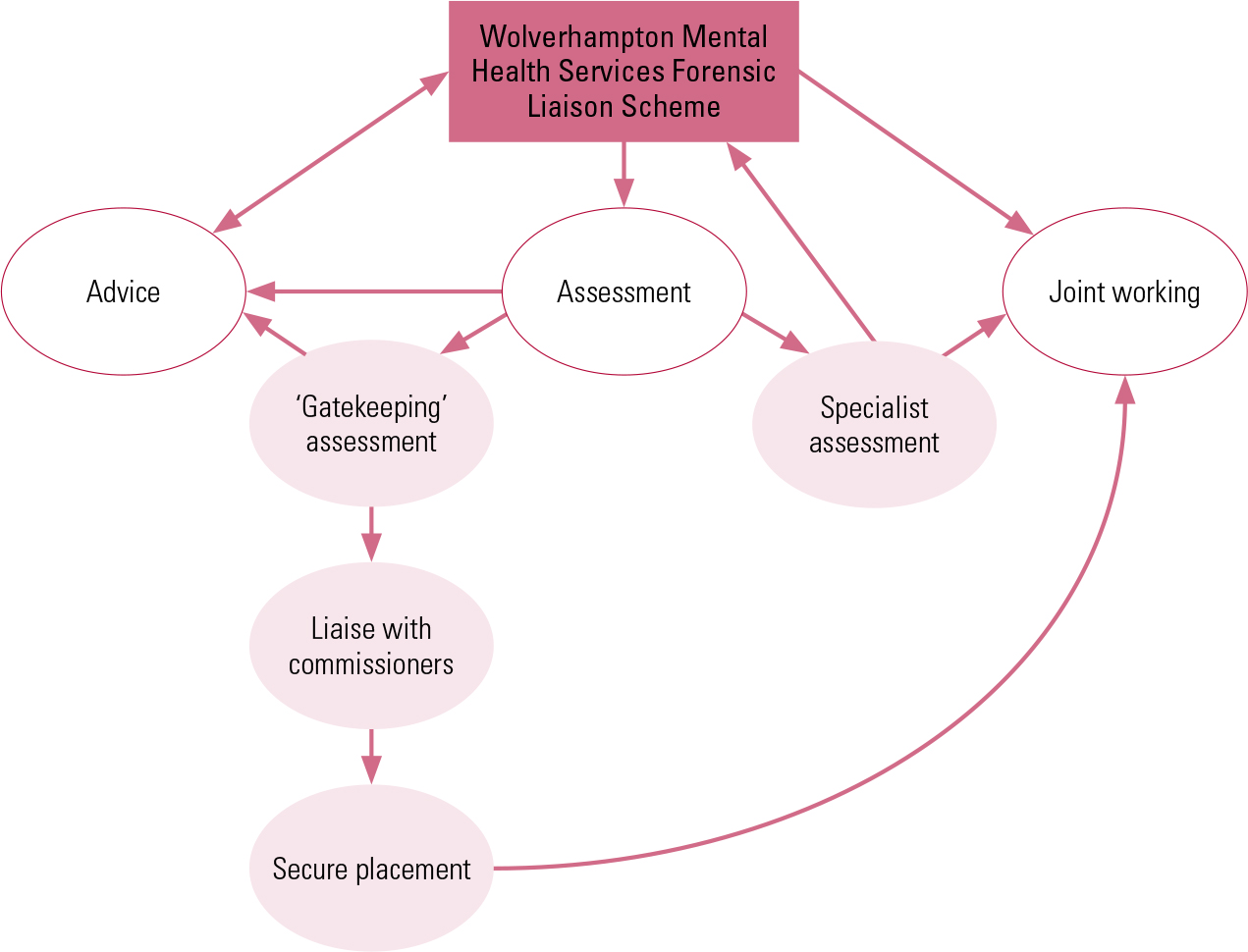

The WMHSFLS is a tertiary service and hence (normally) only accepts referrals from secondary mental health services in Wolverhampton. However, referrals are occasionally also accepted from a wide range of services (Fig. 2). All individuals will have a care coordinator as per the care programme approach. The scheme has devised a form to be completed at the time of referral. Adequate information must be received (e.g. psychiatric reports and risk assessments by the forensic coordinator) for the referral to be processed effectively and promptly. If the referral is urgent, it will be tabled for review at the next scheduled meeting.

FIG 2 Care pathways into the Wolverhampton Mental Health Services Forensic Liaison Scheme.

Agreed referral criteria act only as a guide and the threshold for accepting referrals is fairly low to allow and encourage clinicians who have concerns regarding the risk behaviour of their patient to access a forum where they can discuss these concerns. Normally, patients being referred to the Wolverhampton scheme will have a forensic history and a suspected link between their offending behaviour and mental illness. The scheme will also accept a referral of a patient whose behaviour is causing concern but who has not come into contact with the criminal justice system.

Part of the role of the Wolverhampton scheme is early intervention with individuals whose behaviour/illness is likely to cause them to offend in the near future, in the hope of preventing them from reaching that stage. Care coordinators are expected to attend meetings at which any of their patients is being discussed. This enables continuity of care and is considered good practice. The risk management plan will be discussed, advice given and recommendations made. The scheme’s community mental health nurse will send a letter to all relevant parties outlining the discussions that took place and explicitly stating the recommendations made.

The discharge process

No one is discharged from the Wolverhampton scheme without discussion with the care coordinator. Individuals whose mental health is stable and effectively managed will be the subject of a pre-discharge meeting involving the care coordinator. Discharge from the scheme would be considered if the general adult service did not take up the risk management strategies that the scheme recommended. Those individuals who move out of the area or are discharged from local mental health services will also be considered for discharge from the scheme. In addition to discharge, there could be other possible outcomes (Fig. 3).

FIG 3 Care pathways out of the Wolverhampton Mental Health Services Forensic Liaison Scheme.

Evaluation of the WMHSFLS

In 2007 and 2010, we undertook evaluations of the Wolverhampton scheme. More detailed results appear in the online supplement to this article, and here we give only the key findings.

The operational data that we collected for the scheme in 2007 showed that most individuals referred to it had a psychotic illness and were living in the community. In 2010, a qualitative survey among staff at Wolverhampton Mental Health Services revealed that respondents found the scheme easy to access. The clinical advice/intervention found to be most important and useful to respondents was risk assessment and management. Only a small minority were dissatisfied with the scheme. This survey provided important data on working partnerships and service areas that could be improved and/or changed. Evaluation of the scheme by regular surveys of this type is essential.

Future directions

Liaison forensic psychiatry is an evolving field. An increasing number of services are being commissioned across the country that are adopting some or all of the principles of working in this way. The Bradley Report (Department of Health 2009) recommends cooperation between mental health and criminal justice services to create effective partnership working: it is evident that the experiences of the forensic mental health liaison scheme in Wolverhampton could inform the commissioning and operation of such services. The Wolverhampton scheme already addresses the practicalities of managing people with mental disorder within the criminal justice system, as outlined in the Bradley Report. And as the scheme is (and has been) an evolving service (changing to meet the needs and expectations of local services), we expect to incorporate further principles of the Report.

Conclusions

The liaison model is appropriate for the management of mentally disordered offenders and others who present a risk to the community. It is time- and cost-effective (partly by reducing the time that individuals spend in secure care), reduces the number of inappropriate referrals to forensic services, empowers non-forensic clinicians and allows continuity of care for patients (particularly with the ongoing involvement of local mental health services). The Wolverhampton Mental Health Services Forensic Liaison Scheme is a successful partnership between two NHS trusts and usefully benefits local mental health services. Feedback for the scheme suggests that it is popular with generic services and is perceived as being both open and accessible. We believe that similar successful partnerships can be established more widely across the country.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 A community forensic mental health service can follow the following model:

-

a parallel

-

b collaborative

-

c liaison

-

d mixed

-

e multidisciplinary.

-

-

2 Individual service liaison schemes can be involved with the criminal justice system via:

-

a the Court Engagement and Liaison Scheme

-

b the National Offender Management Service

-

c prison in-reach mental health services

-

d Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements

-

e all of the above.

-

-

3 The following inquiry/report was historically important in the development of community forensic services:

-

a Barrett Inquiry

-

b Glancy Report

-

c Butler Report

-

d Reed Report

-

e Bradley Report.

-

-

4 A key principle of a forensic mental health liaison model is:

-

a shared care

-

b high threshold for referral

-

c intervention at the point of arrest only

-

d a requirement for risk management/assessment to be formulated by local services

-

e acceptance of only those individuals who have had contact with the criminal justice system.

-

-

5 The following is true:

-

a 25% of homicides each year are perpetrated by those with recent contact with mental health services

-

b most services operate a hybrid model

-

c diversion at the point of arrest is an example of a functionalised team

-

d Health and Social Services are integrated in the USA

-

e from the 1970s onwards, psychiatric provision was decentralised in the UK.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | a | 2 | e | 3 | d | 4 | a | 5 | e |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Chris Davies, Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Wroxeter Ward, Shelton Hospital, Shrewsbury, UK for his input on diagrams.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.