Published online Oct 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i10.328

Peer-review started: February 26, 2016

First decision: March 24, 2016

Revised: May 25, 2016

Accepted: June 27, 2016

Article in press: June 29, 2016

Published online: October 16, 2016

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare disorder characterized by peripheral eosinophilia exceeding 1500/mm3, a chronic course, absence of secondary causes, and signs and symptoms of eosinophil-mediated tissue injury. One of the best-characterized forms of HES is the one associated with FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene rearrangement, which was recently demonstrated as responsive to treatment with the small molecule kinase inhibitor drug, imatinib mesylate. Here, we describe the case of a 51-year-old male, whose symptoms satisfied the clinical criteria for HES with cutaneous and cardiac involvement and who also presented with vasculitic brain lesions and retroperitoneal bleeding. Molecular testing, including fluorescence in situ hybridization, of bone marrow and peripheral blood showed no evidence of PDGFR rearrangements. The patient was initially treated with high-dose steroid therapy and then with hydroxyurea, but proved unresponsive to both. Upon subsequent initiation of imatinib mesilate, the patient showed a dramatic improvement in eosinophil count and progressed rapidly through clinical recovery. Long-term follow-up confirmed the efficacy of treatment with low-dose imatinib and with no need of supplemental steroid treatment, notwithstanding the absence of PDGFR rearrangement.

Core tip: Imatinib mesilate is the mainstay therapy of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) associated with molecular rearrangement of the PDGFR gene. To date, HES has been associated with more than 50 different fusion genes resulting from various chromosomal and molecular abnormalities, highlighting the fundamental role of constitutively activated tyrosine kinases in the pathogenesis of this disease; however, few of these genes are routinely researched or detected in the clinical setting. We report a case of HES that showed no evidence of PDGFR rearrangement but responded quickly and effectively to the small molecule kinase inhibitor drug, imatinib mesilate.

- Citation: Fraticelli P, Kafyeke A, Mattioli M, Martino GP, Murri M, Gabrielli A. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting with severe vasculitis successfully treated with imatinib. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(10): 328-332

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i10/328.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i10.328

Eosinophilia is commonly observed in a wide range of disparate reactive/non-clonal and neoplastic/clonal disorders[1,2]. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare disorder characterized by peripheral eosinophilia exceeding 1500/mm3, a chronic course, absence of secondary causes, and signs and symptoms of eosinophil-mediated tissue injury[3]. Diagnosis of HES is made according to the following three Chusid’s criteria: Hypereosinophilia lasting for more than 6 mo, evidence of eosinophil-related organ damage, and exclusion of any other identifiable etiology[4].

Clonal eosinophilia is a hematological disorder defined by the various molecular alterations that underlie its manifestation; studies to date have identified mutations in genes related to tyrosine kinases and their signaling functions, including BCR-ABL, PDGFRA, PDGFRB and c-KIT[5]. The first line of treatment for all cases of HES is high-dose steroids[6], but identification of the specific rearranged clonal form of the disease is important as it can impact the therapeutic outcome. For example, patients with the PDGFRA gene rearrangement respond well to the small molecule kinase inhibitor drug, imatinib mesilate[5,6]. Herein, we present a case in which instrumental and molecular assays showed no evidence of genetic rearrangements and were not able to guide the correct therapeutic strategy; nevertheless, treatment with imatinib mesilate proved an unexpected success in long-term follow-up.

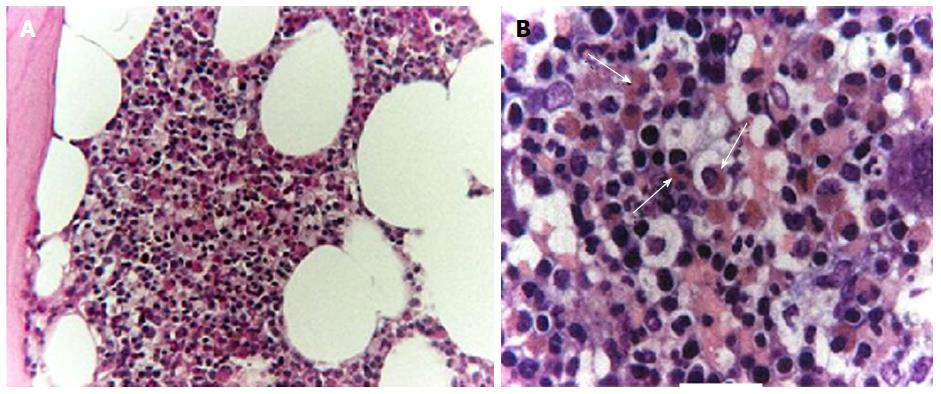

A 51-year-old Caucasian man was transferred to our unit from a different hospital in November 2012. His medical history included occasional events of hypereosinophilia, recorded at 2021/mm3, over the previous 6 mo that were observed during periodic routine check-ups when the patient was noted as being completely asymptomatic. At 3 mo prior, the patient made complaint of fatigue and unintentional weight loss. At 2 mo prior, the patient made complaint of musculoskeletal pain and the treating physician noted new appearance of cutaneous infiltrated nodules; at this point, the patient was treated with symptomatic and local therapy. At 1 mo prior, the patient was admitted to a different hospital for severe dyspnea with elevated cardiac enzymes and echocardiographic signs of infiltrative myocarditis. Allergy, parasitology and hematology testing, including bone marrow biopsy, showed no evidence of allergic/atopic disorders, parasites, or blast cells absence (Figure 1). The test for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) was negative. Analysis of the bone marrow specimens showed a predominant eosinophilic component. Lymphocyte immunophenotyping showed normal T lymphocyte populations both in peripheral blood and bone marrow. Testing by fluorescence in situ hybridization (commonly known as FISH) for PDGFR rearrangement was negative. Further molecular analysis for rearrangements in BCR-ABL, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, WT1 and c-KIT were performed, and all results were negative. During this hospital stay, the patient developed hyposthenia of the left leg and right arm, which was recorded as associated with paresthesias and depressed level of consciousness. A brain computed tomography (CT) scan revealed multiple lesions suspected for vasculitis of the central nervous system (CNS).

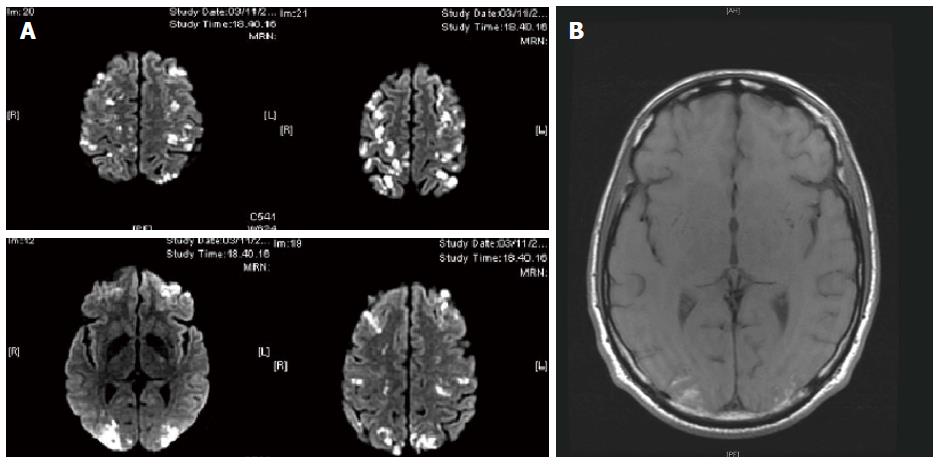

Transfer to our unit was requested. Examination upon arrival showed paresis of the left leg and right arm; the patient was also confused and complained of visual disturbances. Eosinophil count was 25.990/mm3. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the suspicion of CNS vasculitis (Figure 2). Re-test for ANCA produced the same negative result. High-dose methylprednisolone (1 g/d for 3 d), followed by medium-dose methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg per day i.v.) induced rapid improvement of the patient’s neurological condition. However, after 6 d of the medium-dose steroid therapy, the eosinophil count increased to 50.570/mm3. At the same time, hemoglobin dropped suddenly, from 10.9 g/dL to 6.7 g/dL. Abdominal CT indicated active bleeding in the retroperitoneum that was secondary to vasculitic involvement of the lumbar arteries; angiography and embolization was immediately performed and successfully resolved the bleeding. To control the severe hypereosinophilia, hydroxyurea was added to the (steroid) treatment regimen, but was stopped after a short course due to inefficacy. The option of interferon was precluded by the ongoing neurological involvement. Therefore, despite the negative results of the molecular test for PDGFR rearrangement, we decided to begin a regimen of low-dose imatinib mesilate (200 mg/d). We could not perform, to gain further proof of clonality, the G6PD analysis because the patient was a male. After 2 d of treatment, the patient’s eosinophil count normalized, to 100/mm3, and after 1 wk of treatment, the imatinib mesilate dose was reduced to 100 mg/d.

The patient recovered rapidly and was discharged after a total of 22 d hospitalization in our unit, with prescription for continuance of the imatinib mesilate. He continued to have mild visual disturbances and hyposthenia of left leg; the latter of which resolved nearly completely after 3 mo of physical therapy. At 2 mo after discharge, the dose of imatinib mesilate was reduced to 100 mg/twice a week, and at 3 mo after discharge to 100 mg/wk; the dosage then continued for the next year on a tapering-down schedule until the patient’s symptoms resolved completely with consistent normal eosinophil percentage. The lowest dose used was 100 mg every 10 d. At this point, we tried to stop therapy but observed a modest upward trend in the patient’s eosinophil count. Therefore, the imatinib mesilate was reintroduced at the same dose of the last assumption (100 mg every 10 d), and a subsequent normalization of eosinophil count occurred and was maintained thereafter. After 6 mo, we made another attempt to stop the therapy, and the result was better. The stopping of therapy occurred 6 mo prior to the writing of this report. We have a total period of ambulatory follow-up of 36 mo. Currently, the patient is completely asymptomatic, having full recovery of mobility of the involved limbs and no evidence of cardiac sequelae by multiple echocardiographic tests.

Imatinib mesilate is considered a third-line therapy for idiopathic HES, after steroids and hydroxyurea plus interferon, and it is normally used at a medium dosage of 400 mg/die[3,6]. In our case, all Chusid’s criteria were satisfied and the possibility of clonal eosinophilia was excluded following the principal diagnostic chart of hypereosinophilia. Our case’s lack of response to immunosuppressive levels of steroids and hydroxyurea, coupled with the rapid and efficacious complete response to low-dose imatinib mesilate, suggest the presence of a molecular alteration in the PDGFR intracellular pathway, possibly one that is different from those that have been reported to date.

The current literature reports more than 50 different fusion genes resulting from various chromosomal and molecular abnormalities, the dysregulated functions of which have highlighted the fundamental role of constitutively activated tyrosine kinases in the pathogenesis of hypereosinophilic disorders[7]. Not all clinical laboratories have sufficient resources to test all mutations known to be related to clonal HES; as such, case management may consider options associated with the more frequent mutations only. Our case serves as a reminder to not overlook or dismiss an important therapeutic option like imatinib mesilate, which permitted us to control a severe disease state of HES using a low dosage and producing no observable side effects. Therefore, it is possible that in recalcitrant cases, it may be reasonable to attempt a short trial therapy with imatinib mesilate, after the exclusion of any other cause of secondary eosinophilia and according to a very high suspicion of eosinophilic clonal proliferation.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Marco Candela and Maicol Onesta (Internal Medicine Unit, Ospedale “Engles Profili”, 60044 Fabriano, Italy) for referring the patient to us and for supplying information and material obtained before admission into our Unit, and Dr. Gaia Goteri (Pathology Unit, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ospedali Riuniti, 60020 Ancona, Italy) for histopathological images.

A 51-year-old Caucasian man presented with symptomatic hypereosinophilia. His medical history included a 6-mo history of progressive fatigue, unintentional weight loss, musculoskeletal pain and cutaneous infiltrated nodules. The patient also had a 1-mo history of hospital admittance, at another institution, for severe dyspnea.

Echocardiographic signs of infiltrative myocarditis and development of central neurological involvement (visual disturbances and left leg and right arm paresis).

Parasitosis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss), idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES), lymphoproliferative disorder (T/natural killer cells), paraneoplastic syndrome.

Elevated cardiac enzymes; signs of phlogosis and hypereosinophilia (25.990/mm3 at maximum); negative test for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; negative results for PDGFR rearrangement by fluorescence in situ hybridization; negative results for BCR-ABL, PDGFRA, PDGFRB, WT1 or c-KIT by molecular analysis.

Brain computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging revealed multiple lesions suspected for vasculitis of the central nervous system; abdominal CT showed active bleeding in the retroperitoneum that was secondary to vasculitic involvement of the lumbar arteries.

Bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of allergic/atopic disorders, parasites, or blast cells absence.

Imatinib mesilate at 200 mg/d for 1 wk, followed by 100 mg/d according to normalization of eosinophilic count.

Idiopathic HES is a rare disorder characterized by peripheral eosinophilia exceeding 1500/mm3, a chronic course, absence of secondary causes, and signs and symptoms of eosinophil-mediated tissue injury. Several kinds of chromosomal and molecular abnormalities are associated with this disease, such as the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene rearrangement that responds to treatment with imatinib mesilate.

Imatinib mesilate is a direct molecular inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase receptor, and shows therapeutic efficacy for HES associated with the BCR-ABL, c-KIT or PDGFR mutation.

The authors recommend that clinicians managing care of HES cases not forget the therapeutic option of imatinib mesilate, even in the absence of a known mutation. As for the patient described in this case report, the complete response to imatinib mesilate treatment suggests the presence of a molecular alteration in the intracellular pathway related to tyrosine kinase signaling that may be different from the principal ones normally investigated.

In the present case report, Fraticelli et al described the use of a low dose of Imatinib meslate in the treatment of Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. In general, the manuscript is well written.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty Type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of Origin: Italy

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Antica M, Batuman O, Tian XY S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Fletcher S, Bain B. Diagnosis and treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:37-42. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tefferi A, Gotlib J, Pardanani A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome and clonal eosinophilia: point-of-care diagnostic algorithm and treatment update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:158-164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Roufosse F, Gotlib J, Weller PF, Hellmann A, Metzgeroth G, Leiferman KM, Arock M. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:607-612.e9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 460] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chusid MJ, Dale DC, West BC, Wolff SM. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: analysis of fourteen cases with review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975;54:1-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 988] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 982] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cools J, Stover EH, Wlodarska I, Marynen P, Gilliland DG. The FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha kinase in hypereosinophilic syndrome and chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11:51-57. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2014 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:325-337. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Classification and diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 2008 World Health Organization criteria and point-of-care diagnostic algorithms. Leukemia. 2008;22:14-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 706] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 766] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |