The feeding route after esophagectomy: a review of literature

Introduction

Treatment of esophageal cancer has improved over the years by the introduction of neoadjuvant treatment, centralization of care and improved perioperative care (1-3). This has improved overall and cancer specific survival significantly (4,5). Nevertheless, an esophagectomy is still associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.

Postoperative morbidity can be reduced by enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs, which have been successfully implemented in many types of abdominal surgery, including upper gastrointestinal surgery (6). Several components of these programs have already been introduced in esophageal surgery such as prehabilitation programs, minimal invasive surgery and early mobilization, with promising results (7-11). However, the timing and type of postoperative feeding remains a matter of debate for patients undergoing esophagectomy.

Adequate postoperative feeding is especially important since the leading problems in patients with esophageal cancer are dysphagia, weight loss and in some cases malnutrition. Preoperative malnutrition needs to be avoided at any cost, since this is a major determinant of increased morbidity (12,13). Besides the preoperative challenge of keeping patients in a well-nourished state, the esophagectomy and reconstruction with a gastric conduit affects the eating pattern and patient weight (14). Therefore, insight in the optimal preoperative and postoperative feeding regimen is essential to maintain the best patient condition.

In this review, different feeding regimens are discussed together with new insights on early oral feeding.

Artificial nutrition

Fear of (aspiration) pneumonia and a possible aggravation of the sequelae of anastomotic leakage after esophageal surgery are the main reasons to delay the initiation of oral intake. On the other hand malnutrition needs to be avoided, especially in patients after esophagectomy, since anatomical changes as part of the reconstruction alter eating patterns and induce weight loss. Therefore, an artificial feeding route is often used in patients after an esophagectomy to ensure adequate nutritional support.

Artificial enteral nutrition (EN) versus total parenteral nutrition (TPN)

TPN administered directly via a central venous catheter was the first used route to provide adequate nutrition after surgery (15). TPN has been shown to improve wound healing and reduce postoperative complications compared to nil-by-mouth after surgery (16). However, evidence about the potential benefits of artificial EN on the immune response became more vibrant and a number of comparative trials were performed in patients undergoing colorectal surgery, showing the superiority of EN (17-19). Inspired by trials in colorectal surgery, EN was introduced in esophageal surgery (20-24), focusing on feeding route related complications as well as surgical morbidity. Both enteral and parenteral feeding were administered via an artificial feeding route for at least 5–7 days postoperatively and in most studies a nil-by-mouth regimen was applied in this period.

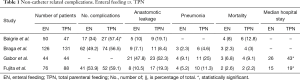

No statistically significant differences were found in the total amount of central venous catheter or enteral feeding tube related complications. However, the incidence of severe complications was higher in patients receiving TPN compared with EN, with an increase in septic complications requiring active interventions, venous thrombosis, electrolyte imbalance and liver failure (21). The characteristics and surgical morbidity of studies with EN and TPN feeding are presented in Table 1. Furthermore, patients with early initiation of TPN in a critically ill state were more likely to develop sepsis, required longer mechanical ventilation and needed longer recovery time compared to late initiation of TPN (25). Mortality rates did not differ between early and late initiation of TPN.

Full table

EN administered via an artificial route (jejunostomy/nasojejunal tube) is also associated with tube related complications, e.g., dislocation, rotation, entry site leakage or infection, abdominal cramps and tube obstruction. The majority of these tube related complications were minor complications that did not hamper recovery after surgery (20). However, also a small number of serious complications were reported in patients receiving a jejunostomy.

Altogether, TPN after esophagectomy is associated with severe catheter-related complications, an increase in infectious complications and costs of this feeding route are relatively high in contrast to EN. TPN should therefore only be used if EN is contra-indicated (e.g., severe chyle leakage).

Jejunostomy feeding

Enteral feeding is now standard of care in most feeding protocols after esophagectomy. The feeding regimen consists of a gradually increasing volume of EN in the first five to seven days. In the majority of patients, a jejunostomy catheter is placed through the skin directly in the proximal jejunum during the esophagectomy. The procedure was first described by Delany et al. and is today considered as the preferred route for administering EN after esophageal surgery (26).

As mentioned before, tube-related complications do occur and could hamper the patients’ recovery after surgery. In a systematic review on the safety and efficacy of different enteral feeding routes, twelve studies (compromising 3,243 patients) reported complications related to jejunostomy feeding (27). A mortality rate of 0–0.5% and a reoperation rate of 0–2.9% was reported. Although the incidence of major complications was limited, minor complications (e.g., dislocation, occlusion, leakage, entry site infection, GI-complaints) occurred frequently with a rate of 13–38%.

Nasojejunal feeding

Nasojejunal or nasoduodenal feeding is an alternative enteral feeding route that is less invasive and potentially associated with a lower incidence of severe complications. During or shortly after surgery a tube is placed via the nasal cavity into the jejunum without creating an artificial entry site in the abdomen. Complications related to nasojejunal feeding are reported in three prospective studies with 135 patients in total (27). No major complications occurred and mortality rates were not described. Frequent dislocation is the main problem with nasojejunal feeding, which occurred in 20–35% of the patients. Occlusion (3%) and GI-complaints (7%) were also reported. The nasojejunal tube is also associated with sore throat and nasal discomfort (28). Additionally, frequent dislocation will put a patient to extra discomfort, as a new tube has to be placed under endoscopic guidance.

One randomized controlled trial including 150 patients compared a surgically placed jejunostomy and nasojejunal tubes after esophageal surgery with cervical anastomosis (29). No significant differences in catheter-related complications between jejunostomy and nasoduodenal feeding were found. However, in 30–40% of the patients a catheter related complication occurred. The majority these complications were minor such as obstruction or dislocation. Jejunostomy insertion was also associated with entry-site infection and leakage in 20% of the patients, resulting in one reoperation. The majority of complications with nasojejunal feeding were related to dislocation (23%). Efficacy of the feeding route was equivalent, patients reaching their nutritional target on the same day [postoperative day (POD) 3, P=0.110].

In conclusion, evidence concerning the superiority of nasojejunal or jejunostomy tube feeding is not yet present. Both methods are used postoperatively and are associated with minor complications.

Direct oral feeding

Early start of oral intake has become standard of care in various types of abdominal surgery over the last years as part of the ERAS program. However, timing of oral intake in esophageal surgery is still under debate.

Early oral feeding after esophagectomy was first documented in a large (N=453) randomized controlled trial performed in five Norwegian hospitals in which oral feeding was initiated on POD 1 (30). Patients were allowed to eat normal (solid) food at will. Postoperative complications were similar in the oral feeding group compared to the group that was given enteral feeding via a jejunostomy tube. Length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the oral feeding group (mean 13.5 vs. 16.7 days, P=0.046). However, in this trial many different upper gastro-intestinal surgical procedures were performed with each different complication rates and time to recovery. Importantly, this trial included a small percentage (<10%) of esophagectomies and therefore, the overall conclusion of this study cannot be extrapolated to all patients undergoing esophagectomy.

Recently, a randomized controlled trial was performed in 109 patients after esophageal (75%) and gastric surgery (31). Early oral feeding commenced on POD 1 and the daily intake increased to a maximum of 1,500 mL when nausea and vomiting were absent. Length of stay (time to discharge or transfer to non-surgical unit) was significantly shorter in the early oral feeding group (6 vs. 8 days, P=0.005) and surgical complication rates did not differ between the groups. A limitation of this study was the possible patient selection bias. Patients who needed ICU admission or had clinical evidence of organ failure, patients with an unstable condition and surgical site infections were excluded. This may confound interpretation of the results and may affect generalizability. Furthermore, when patients were transferred to a non-surgical unit this was scored as total length of stay. This could potentially affect the reliability of the significant change in total length of stay.

The effect of oral feeding on postoperative complications was also demonstrated in a prospective feasibility study in 50 patients (32). Oral feeding was started on POD1 and safety of oral intake was measured in relation to the complication rate (e.g., anastomotic leakage, pneumonia, aspiration, mortality). No significant increase in complication rate was observed, especially regarding anastomotic leakage and pulmonary complications when compared to a historical control group in whom oral intake was delayed until POD5. Patients in the early oral feeding group had a significantly shorter length of stay than in the historic cohort (12 vs. 13 days, P=0.05).

In addition to a potential increase of pulmonary complications due to possible aspiration and a worsening of anastomotic leakage, delayed gastric emptying is often another important argument to postpone oral intake. A prospective cohort trial in China studied the effect of gastric emptying in patients after esophageal surgery with early oral intake (33). The gastric emptying time (GET) was measured preoperative, on POD 1 and POD 7. The GET on POD 1 was significantly shorter in comparison with the preoperative GET (66.4 vs. 23.9 min, P<0.001). The GET remained stable on POD 1 and POD 7 (23.9 vs. 24.1 min, P=0.057). Unfortunately, in the retrospectively collected late oral feeding group GET measurements were not performed. No aspiration of fluid was observed during the GET measurements.

The daily required caloric intake could be a problem in patients receiving early oral intake after surgery, with patients not gaining enough calories in their liquid diet. Weijs et al. documented nutritional intake in patients with early initiation of oral intake (32). Patients were able to reach 58% of their caloric needs on POD 5 with a median intake of 1,205 kcal. However, 30% of the patients in the early oral feeding group received artificial feeding on POD5, mainly because of a complication prohibiting oral intake and in 1 patient due to insufficient intake that day. No data was obtained in the retrospective cohort on caloric intake.

These four studies in patients after esophagectomy suggest that initiation of oral intake directly after surgery is safe and can be considered. However, conclusive evidence is lacking and a randomized controlled trial is needed to substantiate these results. A trial protocol on the initiation of a new randomized controlled trial with early oral feeding after esophagectomy was recently published. Early oral feeding will be compared with delayed oral feeding and the possible benefit of oral intake on postoperative recovery is examined. Furthermore, patients are monitored on their nutritional intake and quality of life (34).

Prolonged delay of oral intake

In contrast to early initiation of oral feeding after an esophagectomy, some groups advocate a prolonged delay of oral intake (up to 4 weeks). Based on the experience in colorectal surgery in which a deviating stoma is sometimes placed in the proximal part of the bowel to ‘protect’ the anastomosis.

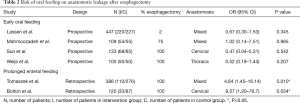

A delay in oral intake and prolonged artificial enteral feeding after esophageal surgery was investigated in two retrospective studies (35,36). Both studies found that a delay in initiation of oral intake up to 4 weeks postoperatively resulted in a lower anastomotic leakage rate and a reduction in length of stay. Table 2 illustrates the risk of anastomotic leakage in patients with a prolonged delay in oral feeding and an early initiation of oral feeding after esophageal surgery.

Full table

Tomaszek et al. retrospectively identified two postoperative feeding regimens after an esophagectomy. Patients in the alternative pathway did not receive oral feeding for 4 weeks. The significant reduction in anastomotic leakage rates was associated with delay in oral intake (OR 0.21; 95% CI: 0.06, 0.69) (35). In addition, the length of stay was shorter in the delayed oral intake group (7 vs. 9 days, P<0.001).

Additionally, Bolton et al. identified two independent predictors of leakage, early oral intake (OR 9.57; 95% CI: 1.2, 76.7) and presence of a respiratory complication (OR 4.02; 95% CI: 1.3, 12.2). Median day of oral intake in this study was POD 12 in the delayed intake group versus initiation of oral intake on POD 5–7 as is considered standard of care in many postoperative protocols.

However, both studies were retrospective and did not register the data in a prospective controlled setting. Other factors, such as difference in surgery period, lack of clear documentation and lack of predefined definitions could potentially have biased these results.

The beneficial effect of a longer delay in initiation of oral intake after esophageal surgery has to be further investigated in large randomized controlled trials.

Conclusions (discussion and recommendations)

This review of the available literature on postoperative feeding highlights the different feeding routes used after esophagectomy.

TPN is no longer the preferred route of postoperative feeding. Early initiation of parenteral nutrition does not improve recovery and is associated with a higher incidence of septic complications (25). In addition, most trials comparing EN and TPN after esophageal surgery found a reduction in severe complications and length of hospitalization in favor of EN (21,22,24). Therefore, the use of TPN after esophageal surgery should be administered only if EN is contraindicated.

EN after esophageal surgery is nowadays the preferred feeding route. Adequate nutritional intake can be maintained and the feeding tube is accompanied with minor complications. Two different feeding routes are used postoperatively and both routes are associated with route-specific complications. Jejunostomy feeding is safe but entry site leakage, infection and occlusion might occur, with a reoperation rate of less than 2% (29). Nasojejunal feeding is less invasive but dislocation occurs frequently, implying frequent replacements are needed. The feeding route chosen remains to be at the preference of the surgeon, since there is no evidence of superiority of one of the routes over the other.

Early oral feeding after esophagectomy is still controversial to this date (37). Fear of increased morbidity is an important argument to delay the start of oral intake within the first PODs. Nevertheless, in line with other types of gastro-intestinal surgery, early initiation of oral intake has been investigated. Four comparative trials did not observe an increased morbidity rate and anastomotic leakage or aspiration incidents did not increase (30-33). However, a large randomized controlled trial in which patients are monitored in a multicenter setting is needed to evaluate the potentially beneficial impact of early oral intake on postoperative recovery and quality of life in patients undergoing esophagectomy.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ando N, Ozawa S, Kitagawa Y, et al. Improvement in the results of surgical treatment of advanced squamous esophageal carcinoma during 15 consecutive years. Ann Surg 2000;232:225-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wouters MW, Karim-Kos HE, le Cessie S, et al. Centralization of esophageal cancer surgery: does it improve clinical outcome? Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:1789-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Law S, Kwong DL, Kwok KF, et al. Improvement in treatment results and long-term survival of patients with esophageal cancer: impact of chemoradiation and change in treatment strategy. Ann Surg 2003;238:339-47; discussion 347-8. [PubMed]

- van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kidane B, Coughlin S, Vogt K, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy for resectable thoracic esophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015.CD001556. [PubMed]

- Spanjersberg WR, Reurings J, Keus F, et al. Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011.CD007635. [PubMed]

- Findlay JM, Gillies RS, Millo J, et al. Enhanced recovery for esophagectomy: a systematic review and evidence-based guidelines. Ann Surg 2014;259:413-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verhage RJ, Hazebroek EJ, Boone J, et al. Minimally invasive surgery compared to open procedures in esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Minerva Chir 2009;64:135-46. [PubMed]

- Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1887-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munitiz V, Martinez-de-Haro LF, Ortiz A, et al. Effectiveness of a written clinical pathway for enhanced recovery after transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 2010;97:714-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang J, Humes DJ, Gemmil E, et al. Reduction in length of stay for patients undergoing oesophageal and gastric resections with implementation of enhanced recovery packages. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013;95:323-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu WH, Cajas-Monson LC, Eisenstein S, et al. Preoperative malnutrition assessments as predictors of postoperative mortality and morbidity in colorectal cancer: an analysis of ACS-NSQIP. Nutr J 2015;14:91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nozoe T, Kimura Y, Ishida M, et al. Correlation of pre-operative nutritional condition with post-operative complications in surgical treatment for oesophageal carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002;28:396-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin L, Lagergren J, Lindblad M, et al. Malnutrition after oesophageal cancer surgery in Sweden. Br J Surg 2007;94:1496-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heyland DK, Montalvo M, MacDonald S, et al. Total parenteral nutrition in the surgical patient: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg 2001;44:102-11. [PubMed]

- Perioperative total parenteral nutrition in surgical patients. The Veterans Affairs Total Parenteral Nutrition Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med 1991;325:525-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore FA, Feliciano DV, Andrassy RJ, et al. Early enteral feeding, compared with parenteral, reduces postoperative septic complications. The results of a meta-analysis. Ann Surg 1992;216:172-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bozzetti F, Braga M, Gianotti L, et al. Postoperative enteral versus parenteral nutrition in malnourished patients with gastrointestinal cancer: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2001;358:1487-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carr CS, Ling KD, Boulos P, et al. Randomised trial of safety and efficacy of immediate postoperative enteral feeding in patients undergoing gastrointestinal resection. BMJ 1996;312:869-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braga M, Gianotti L, Gentilini O, et al. Early postoperative enteral nutrition improves gut oxygenation and reduces costs compared with total parenteral nutrition. Crit Care Med 2001;29:242-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baigrie RJ, Devitt PG, Watkin DS. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition after oesophagogastric surgery: a prospective randomized comparison. Aust N Z J Surg 1996;66:668-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gabor S, Renner H, Matzi V, et al. Early enteral feeding compared with parenteral nutrition after oesophageal or oesophagogastric resection and reconstruction. Br J Nutr 2005;93:509-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seike J, Tangoku A, Yuasa Y, et al. The effect of nutritional support on the immune function in the acute postoperative period after esophageal cancer surgery: total parenteral nutrition versus enteral nutrition. J Med Invest 2011;58:75-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujita T, Daiko H, Nishimura M. Early enteral nutrition reduces the rate of life-threatening complications after thoracic esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer. Eur Surg Res 2012;48:79-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 2011;365:506-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delany HM, Carnevale NJ, Garvey JW. Jejunostomy by a needle catheter technique. Surgery 1973;73:786-90. [PubMed]

- Weijs TJ, Berkelmans GH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, et al. Routes for early enteral nutrition after esophagectomy. A systematic review. Clin Nutr 2015;34:1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tavassoli A, Rajabi MT, Abdollahi A, et al. Efficacy and necessity of nasojejunal tube after gastrectomy. Int J Surg 2011;9:233-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han-Geurts IJ, Hop WC, Verhoef C, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing feeding jejunostomy with nasoduodenal tube placement in patients undergoing oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 2007;94:31-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lassen K, Kjaeve J, Fetveit T, et al. Allowing normal food at will after major upper gastrointestinal surgery does not increase morbidity: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg 2008;247:721-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodzadeh H, Shoar S, Sirati F, et al. Early initiation of oral feeding following upper gastrointestinal tumor surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Today 2015;45:203-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weijs TJ, Berkelmans GH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, et al. Immediate Postoperative Oral Nutrition Following Esophagectomy: A Multicenter Clinical Trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:1141-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun HB, Liu XB, Zhang RX, et al. Early oral feeding following thoracolaparoscopic oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015;47:227-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berkelmans GH, Wilts BJ, Kouwenhoven EA, et al. Nutritional route in oesophageal resection trial II (NUTRIENT II): study protocol for a multicentre open-label randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011979. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tomaszek SC, Cassivi SD, Allen MS, et al. An alternative postoperative pathway reduces length of hospitalisation following oesophagectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:807-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bolton JS, Conway WC, Abbas AE. Planned delay of oral intake after esophagectomy reduces the cervical anastomotic leak rate and hospital length of stay. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:304-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Amico TA. Early feeding after esophagectomy may be too early. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E1067. [Crossref] [PubMed]