- 1Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2Institute of Basic Medicine, Chengde Medical University, Chengde, China

- 3School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China

Candidiasis is often associated with the formation of biofilms. Candida albicans biofilms are inherently resistant to many clinical antifungal agents and have increasingly been found to be the sources of C. albicans infections. Novel antifungal agents against C. albicans biofilms are urgently needed. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of shikonin (SK) against C. albicans biofilms and to clarify the underlying mechanisms. XTT reduction assay showed that SK could not only inhibit the formation of biofilms but also destroy the maintenance of mature biofilms. In a mouse vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) model, the fungal burden was remarkably reduced upon SK treatment. Further study showed that SK could inhibit hyphae formation and reduce cellular surface hydrophobicity (CSH). Real-time reverse transcription-PCR analysis revealed that several hypha- and adhesion-specific genes were differentially expressed in SK-treated biofilm, including the downregulation of ECE1, HWP1, EFG1, CPH1, RAS1, ALS1, ALS3, CSH1 and upregulation of TUP1, NRG1, BCR1. Moreover, SK induced the production of farnesol, a quorum sensing molecule, and exogenous addition of farnesol enhanced the antibiofilm activity of SK. Taken together, these results indicated that SK could be a favorable antifungal agent in the clinical management of C. albicans biofilms.

Introduction

Candida albicans is a pleiomorphic fungal pathogen of humans which may cause superficial to life-threatening infections (Pfaller and Diekema, 2007; Azie et al., 2012). The predisposing factors for C. albicans infections include antibiotic therapy, immunosuppressive therapy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, diabetes and old age. In addition, structured microbial communities attached to medical devices or human organs, commonly referred to as biofilms, have increasingly been found to be the sources of C. albicans infections (Donlan and Costerton, 2002; Gulati and Nobile, 2016). The exist of C. albicans biofilm can exacerbate clinical infections through forming a reservoir for producing recalcitrant pathogenic cells, which act as seeds to disseminate the organism to bloodstream and lead to invasive systemic infection. Moreover, C. albicans biofilms show unique phenotypic traits, the most outstanding of which is that they are notoriously resistant to a wide variety of clinical antifungal agents, including fluconazole and conventional amphotericin B (Chandra et al., 2001; Tobudic et al., 2010; Nett et al., 2011). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new antifungal agents against C. albicans biofilms.

Shikonin (SK) is the major constituent of the red pigment extracts from the roots of the plant Lithospermum erythrorhizon. SK is widely used as a material to prepare an ointment to treat burn, wounds, and hemorrhoids (Vassilios et al., 1999; Sasaki et al., 2002). Besides, SK shows possible therapeutic roles in brain disorders and gastric cancers (Nam et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2014). It has been reported that SK exhibits extensive pharmacological activities, including antiviral, antitumor, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and antithrombotic effects (Chen et al., 2002; Sasaki et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2011; Lan et al., 2014). In our previous studies, we demonstrated the effect of SK against planktonic C. albicans cells, including the azole-resistant clinical isolates (Miao et al., 2012; Liao et al., 2016). However, the role of SK in C. albicans biofilms has not yet been investigated. In this study, we investigated the activity of SK against C. albicans biofilms and explored the underlying mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Media, and Compounds

C. albicans strain SC5314 was obtained from professor Dominique Sanglard (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland). All clinical C. albicans isolates are obtained from Changhai Hospital of Shanghai, China. C. albicans cells were routinely maintained on Sabouraud dextrose agar (1% w/v peptone, 4% w/v dextrose, and 1.8% w/v agar) and grown in YPD liquid medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose) at in an orbital shaker at 30°C (Zhu et al., 2013). For all the experiments in vitro, 6.4 mg/ml SK (purity > 98%, National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Peking, China) in dimethyl sulfoxide and 25 mM farnesol (Sigma-Aldrich, United States) in methanol were used as stock solutions and added to the culture suspensions to obtain the required concentrations. Spider and Lee’s media used for hyphae formation were made as previously described (Gimeno et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1994). RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, United States) was used for biofilm formation experiments.

Antifungal Susceptibility Test

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed in 96-well tissue culture plates (Corning Inc., NY, United States) using a broth microdilution protocol of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M27-A3 method, with a few modifications (Quan et al., 2006). In brief, the initial concentration of fungal cells in RPMI-1640 medium was 5 × 103 CFU/ml, and the final concentrations ranged from 0.125 to 64 μg/ml for SK and fluconazole. Plates were incubated at 35°C for 24 h. The MIC80 was determined as the lowest concentration of the drugs that inhibited growth by 80%.

In vitro Biofilm Formation Assay

The in vitro biofilm formation assay was carried out as described previously (Ramage et al., 2001). In brief, C. albicans cells (1.0 × 106 cells/ml) in RPMI-1640 medium were added to a 96-well tissue culture plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, United States) for 90 min of adhesion at 37°C. For RNA extraction, cells were introduced into a 75 cm2 tissue culture flask (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, United States). Following the initial 90 min of adhesion, the medium was aspirated and non-adherent cells were removed and then fresh medium was added to the adherent cells. The plate was further incubated at 37°C for 24 h until formation of mature biofilms. To test the effect of the compounds (SK, farnesol) on C. albicans biofilm formation, different concentrations of the compounds were added to fresh RPMI-1640 after 90 min of adhesion. To detect the effect of SK on mature C. albicans biofilms, biofilms were formed at 37°C for 24 h as described above. The biofilms were washed with PBS, then fresh RPMI-1640 medium containing different concentrations of SK was added. The plates were incubated at 37°C for a further 24 h to detect the antibiofilm effect of SK.

XTT Reduction Assay

The growth of biofilms was measured with a 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5- sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) reduction assay, a reaction catalyzed by mitochondrial dehydrogenases (Ramage et al., 2001). In brief, biofilm cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with 0.5 mg/ml of XTT and 1 mM of menadione in PBS at 37°C for 90 min. The optical density (OD) was determined at 490 nm using a microtiter plate reader. The SMIC80 was determined as the lowest concentration of the drugs that inhibited mature biofilm by 80%.

Biofilm Biomass Measurement

The measurement of biofilm biomass was conducted as described previously (Nobile et al., 2006) with slight modifications. Silicone disks (1.5 × 1.5 cm, Bentec Medical Corp., United States) were weighed before inoculation. C. albicans cells (1.0 × 106 cells/ml) in RPMI-1640 medium were added to a 12-well tissue culture plate with one prepared silicone disk in each well. The inoculated plate was incubated with for 90 min at 37°C. Then the medium was aspirated, non-adherent cells were removed and fresh medium was added to the adherent cells. The plate was further incubated gentle agitation at 37°C for 24 h until the formation of mature biofilms. To test the effect of SK on biomass production, different concentrations of SK were added to fresh RPMI-1640 after 90 min of adhesion. The silicone disks with attached biofilms were removed from the wells, dried overnight and weighed. The total biomass of biofilm was calculated by subtracting the weight of the silicone prior to biofilm growth from the weight of the silicone after the drying period, with adjustment for the weight of control silicone squares exposed to no cells.

Hyphae Formation

Three hypha-inducing media (Lee’s medium, Spider medium and YPD medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum) was used to test the effect of SK on hyphal formation. C. albicans (5.0 × 105 cells/ml) were suspended in the hypha-inducing media containing 0.5 μg/ml of SK and added to 24-well tissue culture plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The morphology of the cells was photographed under microscope.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

To observe the effect of SK on C. albicans biofilms formation with CLSM, siliconedisks (Bentec Medical Corp., United States) were used to develop biofilms. Biofilms were washed and incubated for 45 min at 37°C in PBS containing the fluorescent stains FUN-1 (10 μM) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, United States) and concanavalin A-Alexa Fluor488 conjugate (ConA) (25 μg/ml) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, United States). FUN-1 is converted to an orange-red cylindrical intravacuolar structure by metabolically active cells, whilst ConA binds to the glucose and mannose residues of cell wall polysaccharides and emits a green fluorescence. After incubation with the dyes, the disks were flipped and the stained biofilms were observed with a Leica TCS SP2 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with argon and HeNe lasers.

Farnesol Measurement

Farnesol was extracted and measured as previously described (Hornby et al., 2001) with some modificaton. In brief, the supernatant of C. albicans biofilm treated with SK for 24 h was collected. The biofilm cells were scraped from the culture plate and filtered through filters (0.45 μm) and washed three times with ultrapure sterilized water. Cells were dried at room temperature to constant weight and weighed using an electronic balance. Farnesol in the supernatants was extracted using ethyl acetate and detected with HPLC (Agilent, United States). The detection was performed by absorbance at 210 nm. A 5 mm C18 reversed-phase column (4.6 by 250 mm) was utilized with a mobile phase of 4:1 methanol-H2O eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Six different concentrations of farnesol standard samples were used to create a standard curve of integral areas eluting at its retention time. The extracted farnesol was calculated based on the HPLC integral area compared with a standard curve. Farnesol concentrations obtained from each culture were also normalized on the biofilm dry weight assays.

Cellular Surface Hydrophobicity(CSH) Assay

The cellular surface hydrophobicity (CSH) of C. albicans biofilms was determined by a water-hydrocarbon two-phase assay as described previously (Klotz et al., 1985). In brief, the formed C. albicans biofilms were removed from the culture plate surface with a sterile scraper to obtain a cell suspension (OD600 = 1.0 in YPD medium). A total of 1.2 ml of the suspension was pipetted into a clean glass tube and overlaid with 0.3 ml of octane. The mixture was vortexed for 3 min and then stood at room temperature for phase separation. Soon after the two phases had separated, the OD600 of the aqueous phase was determined, and the OD600for the group without the octane overlay was used as the control. Relative CSH was calculated as follows: [(OD600 of the control-OD600 after octane overlay)/OD600of the control] × 100.

Real-Time RT-PCR

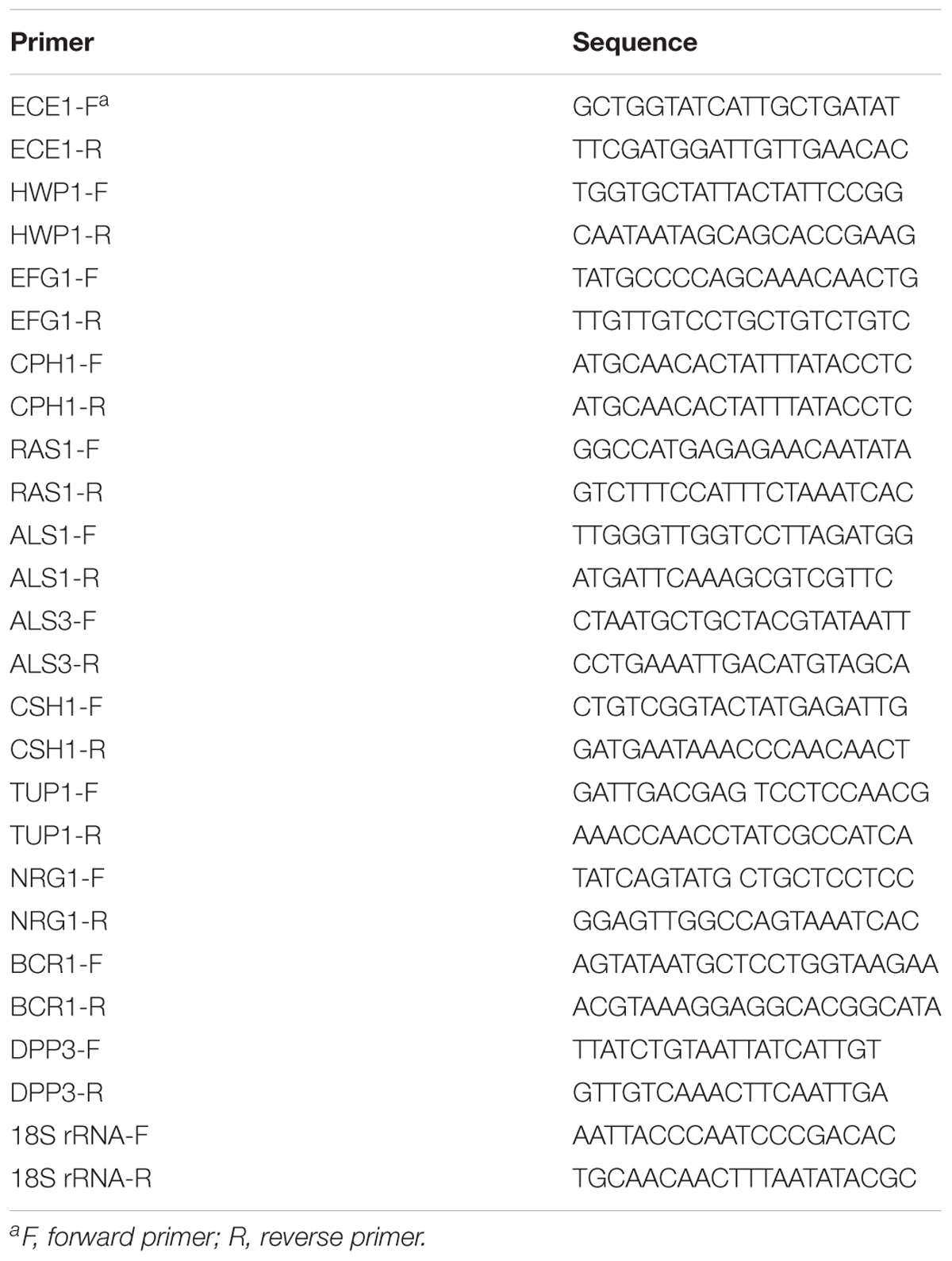

RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR were performed as described previously (Li et al., 2014). Total RNA was isolated with fungal RNAout kit (TIANZ, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The isolated RNA was resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. The OD was measured at 260 nm and 280 nm. The integrity of the RNA was visualized by subjecting 2–5 μl of the samples to electrophoresis through a 1% agarose-MOPS gel. The cDNA was obtained using the cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT-PCR (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). Real-time PCR was performed with a 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). SYBR green I (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) was used to monitor the amplified products in real time according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The primers are shown in Table 1. The PCR protocol consisted of denaturation program (95°C for 10 s), 40 cycles of amplification and quantification program (95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 20 s, 72°C for 15 s with a single fluorescence measurement), melting curve program (60–95°C with a heating rate of 0.1°C per second and a continuous fluorescence measurement) and finally a cooling step to 40°C. The expression of each gene was normalized to that of 18S rRNA. The relative expression of each target gene was calibrated against the corresponding expression in untreated biofilms.

Evaluation of in vivo Antifungal Activity

A mouse vaginal model was used to demonstrate the antifungal effect of SK in vivo according to the previous procedures with slight modification (Yano and Fidel, 2011). Briefly, 3 days prior to inoculation, female KM clean mice (Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Center, China) were injected with 0.1 mg of β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) subcutaneously in the lower abdomen. Estrogens injections were administered every other day for three times in a week. The intravaginal inoculation with 4 × 106 C. albicans cells in 20 μl of PBS was injected into vaginal lumen of the estrogen-treated mice. After the establishment of murine model, SK (dissovled in sesame oil) was delivered intravaginally on days 1, 2, 3, and 4 after inoculation. Sesame oil was employed as a negative control. On the fifth day, the vaginal lumens of the mice were lavaged by 100 μl of PBS with repeated aspiration and agitation with a pipette tip. The lavage fluids were picked and cultured on the YPD plates. The CFU was counted to analyzed the infection burdens. The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China).

Statistical Criteria

Statistics were calculated in GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States), in which P-value of < 0.05 or < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

SK Inhibits C. albicans Biofilms

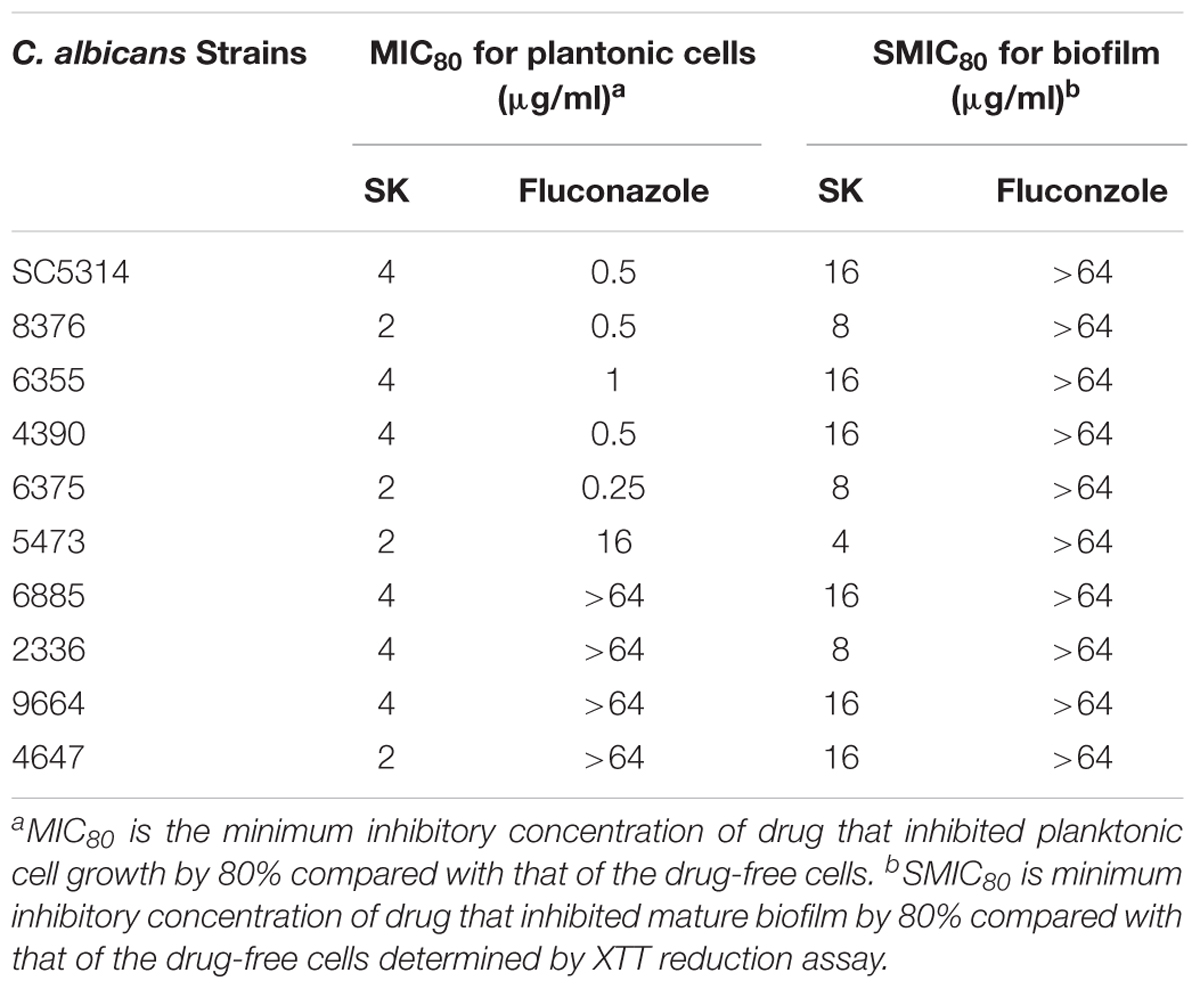

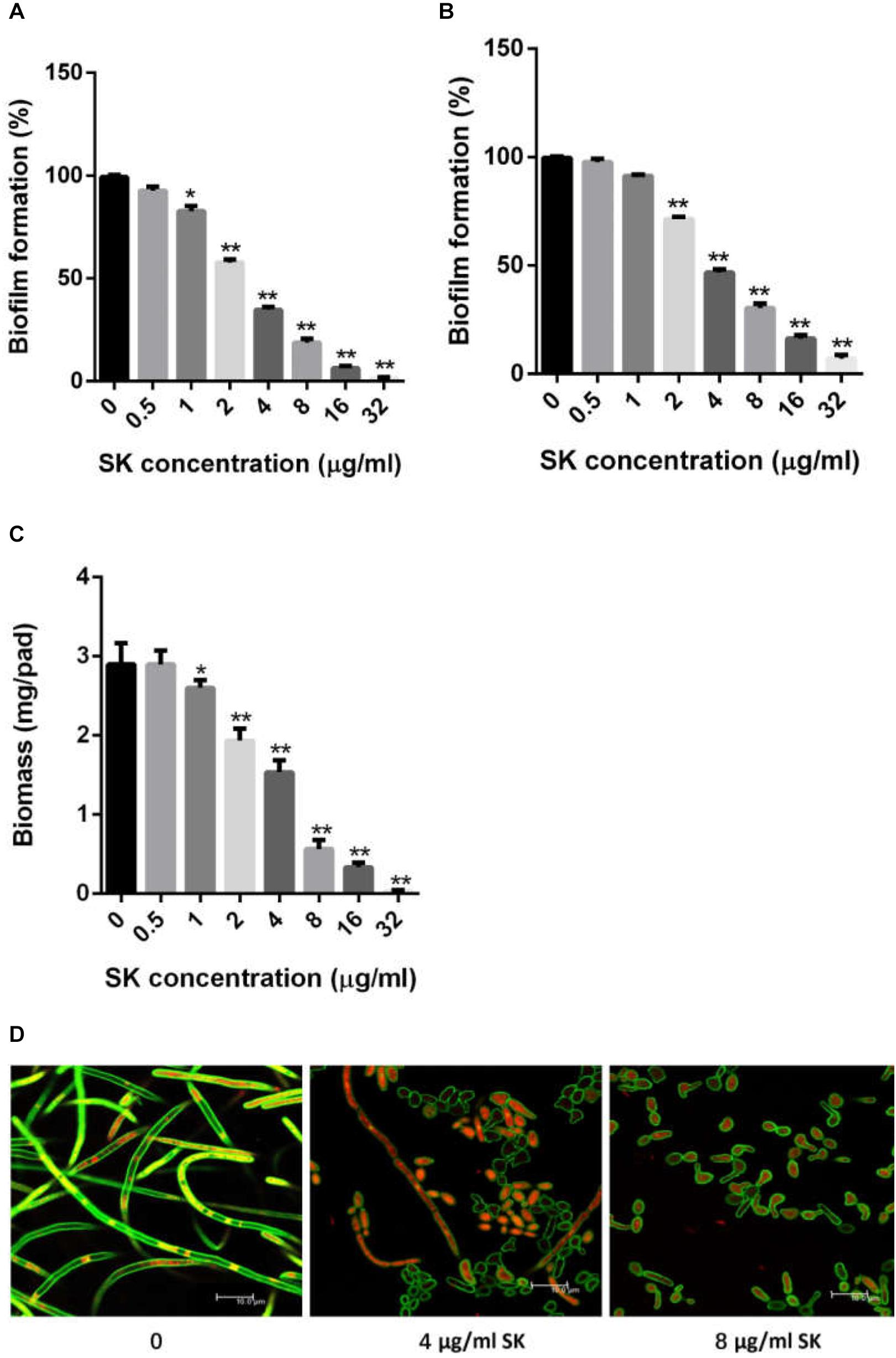

We first determined the MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values of SK on C. albicans strains, including a standard strain SC5314 and several clinical isolates. As shown in Table 2, SK could inhibit both planktonic and biofilm cells. The MIC80s of SK against plantonic C. albicans cells ranged from 2 to 4 μg/ml. It should be noted that SK exhibited similar antifungal activity on the fluconazole-resistant strains as the fluconazole-sensitive strains. The SMIC80s of SK against C. albicans mature biofilms ranged from 4 to 16 μg/ml while the SMIC80s of fluconazole were over 64 μg/ml. Figure 1A showed that SK inhibited biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner when this compound was added to C. albicans cells after 90 min of adhesion. More specifically, 1 μg/ml of SK inhibited biofilm formation by 17.3%, and the inhibitory effect on biofilm formation was enhanced when the concentration of SK was increased. 4 μg/ml of SK inhibited biofilm formation by 65.4%, while the biofilm growth was almost totally inhibited upon exposure to 32 μg/ml of SK. The effect of SK against mature C. albicans biofilms was shown in Figure 1B. Although the mature biofilm cells were hardly affected at the SK concentrations of less than 1 μg/ml, almost half of the mature biofilm was destroyed when SK was added at the concentration of 4 μg/ml. SK at the concentration of 32 μg/ml destroyed mature biofilms by 92.8%.

Figure 1. SK inhibits C. albicans biofilms in vitro. (A) Effects of different concentrations of SK on biofilm formation. (B) Effects of different concentrations of SK on mature biofilms. (C) Effects of different concentrations of SK on biofilms formation determined by biomass production. (D) Effects of different concentrations of SK on biofilm formation, shown in CLSM images. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the independent assays in triplicate. ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01 as compared to the SK-free group.

Consistent with the results of the XTT reduction assay, biofilm biomass determination revealed that SK could inhibit biomass production (Figure 1C). Addition of 1 μg/ml of SK led to a significant drop of biomass level as compared to the control group without SK treatment. The inhibitory effect on biomass production was enhanced when the concentration of SK was increased, while almost no biomass was produced in the presence of 32 μg/ml of SK.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) analysis further confirmed the antibiofilm activity of SK. In the SK-free group, C. albicans biofilm exhibited atypical three-dimensional nature, composed mainly of true hyphae. However, the structure of C. albicans biofilm was destroyed in the presence of SK. At the concentration of 4 μg/ml of SK, the biofilm was predominantly composed of yeast cells and pseudohyphae, while true hyphae were rarely observed. When 8 μg/ml of SK was added, the C. albicans biofilm displayed a poor architecture, with a complete disappear of true hyphae or pseudohyphae (Figure 1D).

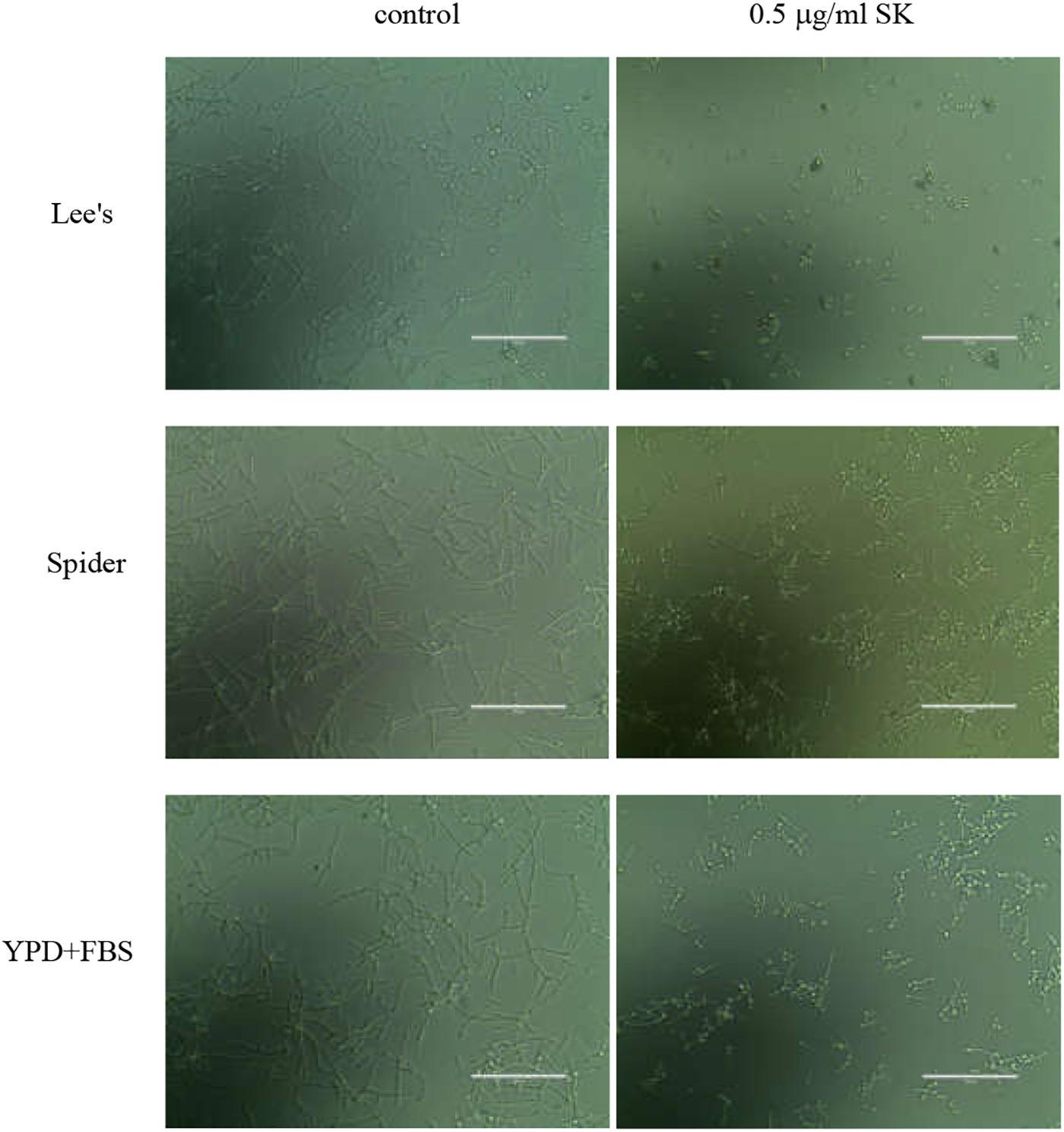

SK Inhibits C. albicans Hyphae Formation

Since yeast-to-hypha growth is a key factor in C. albicans biofilm formation and virulence, we tested the effect of SK on filamentous growth. C. albicans cells were cultured in various hypha-inducing media, including Lee’s, Spider and YPD liquid media containing 10% fetal bovine serum. As shown in Figure 2, in the absence of SK, C. albicans underwent hyphal initiation, produced elongated and regular hyphal cells. When 0.5 μg/ml SK was added, the filamentous growth was remarkably inhibited. Specifically, the filamentation in Lee’s media was completely inhibited by 0.5 μg/ml of SK as only yeast cells were observed.

Figure 2. Effects of SK on hyphae formation. C. albicans SC5314 cells were incubated in Lee’s, Spider or YPD liquid media supplemented by 10% fetal bovine serum (YPD + FBS). The cellular morphology was photographed after incubation at 37°C for 3 h.

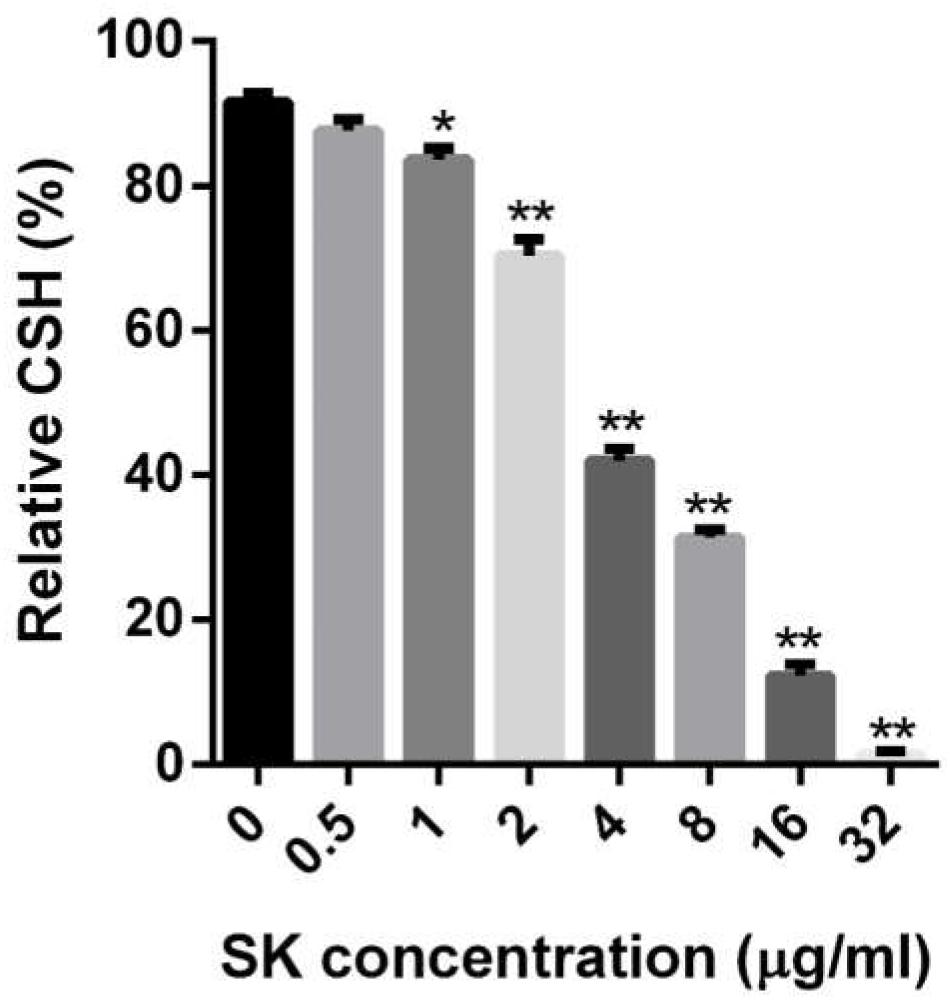

SK Reduces Cellular Surface Hydrophobicity of C. albicans Biofilm

The CSH is an important factor for cell adhesion and biofilm formation, so we determined the CSH of C. albicans biofilms upon SK treatment. As shown in Figure 3, a negative correlation was observed between SK concentrations and the CSH of C. albicans biofilms. The relative CSH of untreated C. albicans biofilm was high (about 91.7%). SK decreased the CSH of biofilms in a dose-dependent manner. When the biofilm was treated with 2 μg/ml of SK, the relative CSH was significantly reduced, to approximately 70.3%. The relative CSH of the biofilm almost reached zero following the treatment of 32 μg/ml of SK.

Figure 3. Effects of different concentrations of SK on the cell surface hydrophobicity (CSH) of C. albicans biofilms. CSH was estimated by the water-hydrocarbon two-phase assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the independent assays in triplicate.∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01 as compared to the SK-free group.

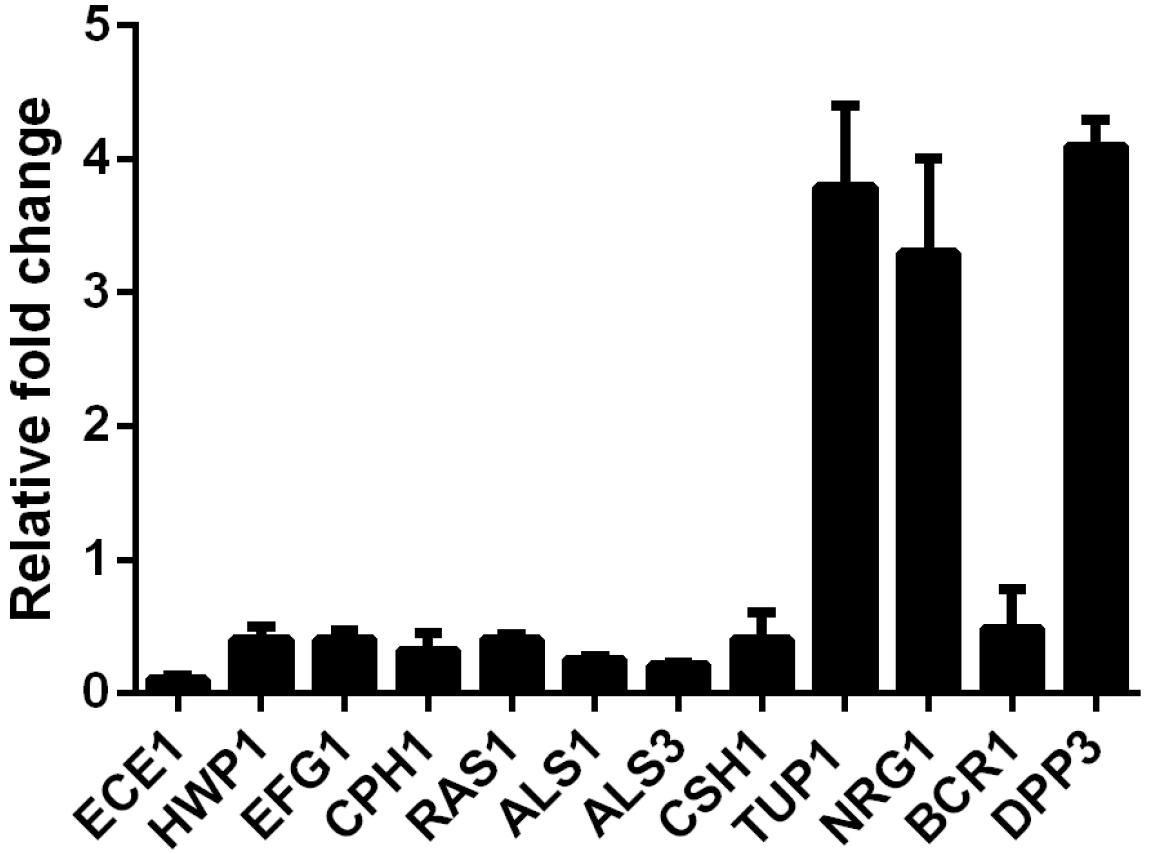

SK Regulates the Hypha- and Adhesion-Specific Genes Expression

In view of the inhibition of SK on C. albicans filamentous growth and adhesion, we investigated the expression of several well-known genes involved in hyphae formation and adhesion. In this experiment, 2 μg/ml of SK was used to inhibit biofilm formation for 8 h. The real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) results showed that ECE1, HWP1, EFG1, CPH1, RAS1, ALS1, ALS3, and CSH1 were downregulated. The upregulated genes included TUP1, NRG1, and BCR1 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Transcription levels of several C. albicans genes following treatment with 2 μg/ml of SK were detected by real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). The mRNA levels were normalized on the basis of their 18S rRNA levels. Gene expression was indicated as the fold increase in SK-treated biofilm cells relative to that of the untreated biofilm cells. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the independent assays in triplicate.

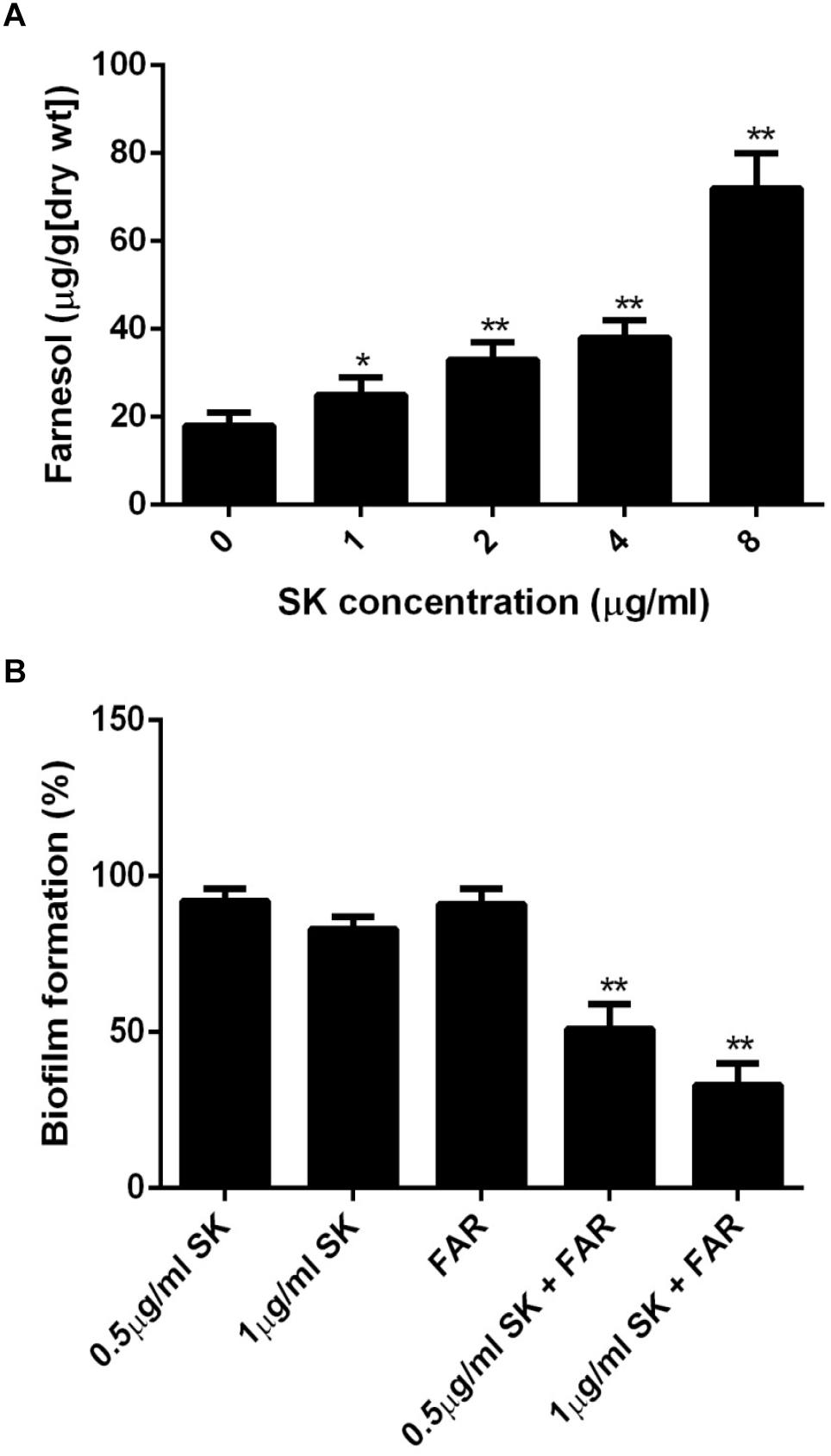

SK Induces Farnesol Production

It has been reported that farnesol, one of the quorum sensing molecules in C. albicans, played an important role in yeast-to-hypha transition and biofilm formation (Ramage et al., 2002). In view of the inhibition of hyphae and biofilm formation upon SK treatment, we hypothesized that SK might exert this effect through modulating the level of farnesol. As expected, our results revealed that SK increased the production of farnesol in a dose-dependent manner. The level of farnesol was four times higher in 8 μg/ml of SK-treated biofilm than that in SK-free biofilm (Figure 5A). Consistent with this, DPP3, which encodes a phosphatase and has been demonstrated to be responsible for farnesol synthesis by converting farnesyl pyrophosphate to farnesol (Navarathna et al., 2007), was remarkably upregulated upon SK treatment (Figure 4).

Figure 5. (A) Farnesol production in the supernatant of C. albicans biofilms treated with different concentrations of SK for 24 h. (B) Effect of farnesol on the antibiofilm activity of SK. C. albicans cells were cultured in biofilm formation condition. After 90 min of adhesion, SK (0.5, 1 μg/ml) or farnesol (25 μM) or the combination of the two compounds were added and the biofilm growth was continued for 24 h. Biofilm formation was evaluated using an XTT reduction assay, and the results are presented as the percent of compound-treated biofilms relative to the control (compound-free) biofilm. The results represent means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments. ∗∗P < 0.01 as compared to the corresponding SK-treated alone group.

Farnesol Enhances the Antibiofilm Activity of SK

Since the level of farnesol was increased upon SK treatment, we investigated the effect of farnesol on the antibiofilm activity of SK. To this end, the concentrations of SK (0.5 and 1 μg/ml) that had only a slight impact on biofilm formation were used. Similarly, 25 μM of farnesol used alone had no significant effect on biofilm. When SK was used in combination with farnesol, the formation of biofilms was significantly inhibited. More specifically, the combined treatment of 1 μg/ml of SK and 25 μM of farnesol resulted in approximately 40% biofilm formation rate as compared to drug-free biofilm (Figure 5B).

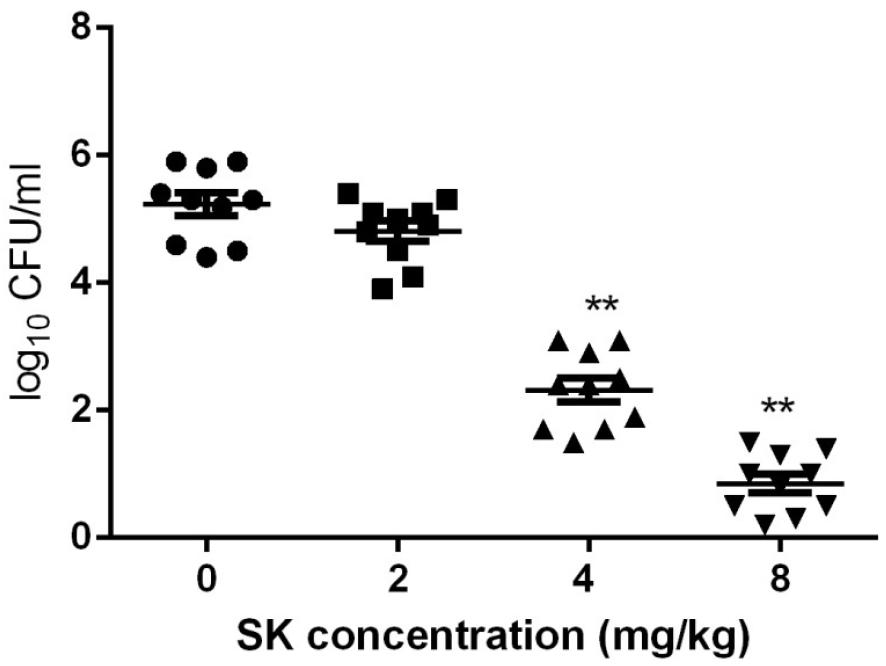

In vivo Activity of SK on C. albicans

Since C. albicans is believed to be commonly occurred in vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) and VVC infections mainly rely on biofilm formation (Sobel et al., 1998; Fazly et al., 2013), here the in vivo activity of SK was investigated using a mouse vaginal infection model. As shown in Figure 6, although treatment of 2 mg/kg of SK had a slight impact on the fungal burden, 4 mg/kg of SK-treated group showed approximately 3 log10 CFU/ml reduction of fungal burden as compared to the control (SK-free) group. There was an even remarkable drop of fungal burden when SK was administrated at the dose of 8 mg/kg, while the fungal cells seemed to be wiped out.

Figure 6. Fungal burden analyses by colony counting after the administrations of SK in a mouse vaginal model. Statistical significance among the groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗∗P < 0.01 as compared to the values from the SK-free group.

Discussion

An important reason for the failure of current antifungal therapy is attributed to the formation of biofilms which are inherently resistant to most antifungal treatments. Thus, there is an urgent need for new antifungal drugs that can efficiently inhibit biofilms (Donlan and Costerton, 2002). In this study, a strong inhibitory effect of SK against C. albicans biofilms was revealed. More importantly, SK could not only inhibit the formation of C. albicans biofilms but also destroyed the maintenance of mature biofilms. The antifungal activity of SK was further confirmed in a mouse model of VVC. The mechanisms for the antibiofilm activity of SK included the inhibition of hyphae formation and adhesion as well as enhanced farnesol production.

The antifungal agents used in the treatment of C. albicans infections mainly include azoles (e.g., fluconazole and itraconaole), polyenes (e.g., amphotericin B) and echinocandins (e.g., caspofungin and micafungin). Although treatment of C. albicans biofilm was shown to be effective with polyenes and echinocandins in several reports, high drug resistance occurs in biofilms of C. albicans when treated with azoles, especially fluconazole which is widely used in clinical practice due to its relatively low cost and side effect (Anderson, 2005; Mukherjee et al., 2009; Kucharicová et al., 2013). It was reported that fluconazole could hardly affect mature C. albicans biofilm (Chandra et al., 2001). In this study, the antifungal effect of SK was outstanding as compared to fluconazole. SK could effectively inhibit C. albicans biofilm and 32 μg/ml of SK could destroy over 90% of mature biofilms, while the SMIC80 of fluconazole was over 64 μg/ml.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is the second most common infection disease in female genitourinary tract, and C. albicans is considered as the most common pathogen in this disease (Achkar and Fries, 2010; Spence, 2010). Recent studies reveal that VVC infections mainly rely on the formation of C. albicans biofilm and have been commonly used for in vivo evaluation of antibiofilm compounds (Gao et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018). To evaluate the antibiofilm activity of SK in vivo, we chose a mouse VVC model. We found that SK could significantly alleviate vaginal fungal burden at the dose of 4 mg/kg. Moreover, when SK was administrated at the dose of 8 mg/kg, the fungal cells seemed to be wiped out. Collectively, our findings indicated that SK might exhibit great potential as a novel antibiofilm compound.

In recent years, cell-cell signaling, particularly quorum sensing, has been one of the focuses of microbiological research. C. albicans can produce farnesol as an extracellular quorum-sensing molecule, which is also the first quorum-sensing molecule discovered in a eukaryote (Shirtliff et al., 2009; Polke et al., 2018). It has been proved that farnesol inhibits C. albicans biofilm formation (Hornby et al., 2001; Kebaara et al., 2008). Here we found that SK could enhance farnesol production in C. albicans biofilms. Consistently, the expression of DPP3, the key gene involved in farnesol synthesis, was remarkably upregulated upon SK treatment. Previous studies demonstrated that farnesol exerted a synergistic or additive interaction with antifungal agents, including micafungin, fluconazole and amphotericin B, against C. albicans biofilms (Cordeiro et al., 2013). Similarly, our study showed that the combination of SK and farnesol resulted in a much higher antibiofilm activity than SK used alone. These results indicated that farnesol might play an important role in the antibiofilm mechanisms of SK.

In C. albicans, inhibition of yeast-to-hypha transition is a key role for farnesol. In fact, hyphal morphogenesis is required to establish robust biofilm with complex three-dimensional structure, and interruption of the yeast-to-hypha transition would prevent biofilm development. In this study, the structure of biofilm was destroyed by SK in a dose-dependent manner, and treatment of 8 μg/ml SK resulted in a poor biofilm architecture, with a complete disappear of true hyphae or pseudohyphae. The inhibition of filamentous growth by SK was also confirmed in hypha-inducing liquid media. These results were consistent with the inhibitory activity of farnesol on C. albicans morphological transition.

To uncover the underlying molecular basis of inhibited morphological transition and cell adhesion by SK, we assessed the transcription levels of genes related to hyphal growth and adhesion. Our real-time RT-PCR analysis revealed that several important hypha- and adhesion-specific genes were differentially expressed upon SK treatment. HWP1 is uniquely expressed on the hyphal surface, and biofilms lacking HWP1 were prone to detach from the abiotic substrate (Chaffin, 2008). RAS1 belongs to the Ras1-cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway, a key regulator of the yeast-to-hypha switch and biofilm formation (Davis-Hanna et al., 2008). EFG1 and CPH1 are major transcription regulators of filamentous growth controlling many signaling pathways involved in filamentation (Nobile et al., 2012; Araújo et al., 2017). BCR1 is a transcriptional factor that regulates the adhesive properties of hyphal cells by affecting the expression of cell wall and adhesin genes, including members of the ALS family and HWP1 (Nobile and Mitchell, 2005; Nobile et al., 2006). The downregulation of these genes may contribution to reduced hyphae formation and thus biofilm inhibition. TUP1 encodes a global transcriptional corepressor, repressing the expression of hypha-specific genes. A tup1Δ mutant displays hyper filamentation under conditions favorable for growth of the yeast form (Braun and Johnson, 1997, 2000). NRG1, which acts in concert with TUP1, encodes another transcriptional repressor. Hyper-filamentation is also observed upon the loss of either NRG1 or TUP1 (Braun et al., 2001). SK may inhibit filamentous growth of C. albicans by upregulating of TUP1 and NRG1. It should be noted that most of these genes can be regulated by farnesol. In our previous study, TUP1 was overexpressed in farnesol-treated C. albicans biofilm (Cao et al., 2005). Davis-Hanna et al. and other groups demonstrated the impact of Ras1-Cdc35-Efg1 signaling pathway as well as the downstream Hwp1 by farnesol (Davis-Hanna et al., 2008; Lindsay et al., 2012). Nevertheless, further studies are required to explore whether SK inhibits hyphae formation through enhancing farnesol production.

The formation of C. albicans biofilm includes three main stages: adhesion to biomaterial surfaces, growth to form an anchoring layer, and morphological transition to form a complex three-dimensional structure. CSH, which contributes to the interaction between the cells and the surfaces, is an important factor for cell adhesion (Luo and Samaranayake, 2002; Seneviratne et al., 2008). A positive correlation between biofilm formation and CSH has been reported in several studies (Samaranayake et al., 1995; Luo and Samaranayake, 2002; Pompilio et al., 2008). Previous studies revealed that CSH is correlated with cell adhesion, which is the first and important stage for biofilm formation (Luo and Samaranayake, 2002; Seneviratne et al., 2008). In this study, exposure of C. albicans biofilm to SK led to decreased CSH. Consistent with this, CSH1, which codes for a key CSH-associated protein, was downregulated upon SK treatment. In our previous study on the mechanisms of farnesol against C. albicans biofilm, farnesol could decrease CSH in a dose-dependent manner (Cao et al., 2005). Besides the downregulation of CSH1, the expression of ALS1 and ALS3, two ALS family genes that plays an essential role in promoting cell adhesion and biofilm formation (Sundstrom, 2002; Tronchin et al., 2008), were also decreased. These results implicated that SK might impede the initial adhesion of C. albicans cells, thus prevent biofilm formation.

Taken together, our study revealed the strong activity of SK against C. albicans biofilms and extended its potential application against biofilm-related fungal infection.

Ethics Statement

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China).

Author Contributions

YC conceived and designed the experiments. YY, HM, FT, and HW performed the experiments. YY, FT, and YC analyzed the data. YC wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671991).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank William A. Fonzi (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC) for providing C. albicans strain SC5314. We also thank Prof. Gu Jun (Changhai Hospital of Shanghai, China) for providing the clinical C. albicans isolates.

References

Achkar, J. M., and Fries, B. C. (2010). Candida infections of the genitourinary tract. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 253–273. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00076-09

Anderson, J. B. (2005). Evolution of antifungal-drug resistance: mechanisms and pathogen fitness. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 547–556. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1179

Araújo, D., Henriques, M., and Silva, S. (2017). Portrait of Candida species biofilm regulatory network genes. Trends Microbiol. 25, 62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.004

Azie, N., Neofytos, D., Pfaller, M., Meier-Kriesche, H. U., Quan, S. P., and Horn, D. (2012). The PATH (Prospective Antifungal Therapy) alliance registry and invasive fungal infections: update 2012. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 73, 293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.06.012

Braun, B. R., and Johnson, A. D. (1997). Control of filament formation in Candida albicans by the transcriptional repressor TUP1. Science 277, 105–109. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.105

Braun, B. R., and Johnson, A. D. (2000). TUP1, CPH1 and EFG1 make independent contributions to filamentation in Candida albicans. Genetics 155, 57–67.

Braun, B. R., Kadosh, D., and Johnson, A. D. (2001). NRG1, a repressor of filamen- tous growth in C. albicans, is down-regulated during filament induction. EMBO J. 20, 4753–4761. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4753

Cao, Y. Y., Cao, Y. B., Xu, Z., Ying, K., Li, Y., Xie, Y., et al. (2005). cDNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Candida albicans biofilm exposed to farnesol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 584–589. doi: 10.1128/aac.49.2.584-589.2005

Chaffin, W. L. (2008). Candida albicans cell wall proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 495–544. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00032-07

Chandra, J., Mukherjee, P. K., Leidich, S. D., Faddoul, F. F., Hoyer, L. L., Douglas, L. J., et al. (2001). Antifungal resistance of candida biofilms formed on denture acrylic in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 80, 903–908. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800031101

Chen, X., Yang, L., Oppenheim, J. J., and Howard, M. Z. (2002). Cellular pharmacology studies ofshikonin derivatives. Phytother. Res. 16, 199–209. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1100

Cordeiro, R. A., Teixeira, C. E., Brilhante, R. S., Castelo-Branco, D. S., Paiva, M. A., GiffoniLeite, J. J., et al. (2013). Minimum inhibitory concentrations of amphotericin B, azoles and caspofungin against Candida species are reduced by farnesol. Med. Mycol. 51, 53–59. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.692489

Davis-Hanna, A., Piispanen, A. E., Stateva, L. I., and Hogan, D. A. (2008). Farnesol and dodecanol effects on the Candida albicans Ras1-cAMP signalling pathway and the regulation of morphogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 67, 47–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06013.x

Donlan, R. M., and Costerton, J. W. (2002). Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 167–193. doi: 10.1128/cmr.15.2.167-193.2002

Fazly, A., Jain, C., Dehner, A. C., Issi, L., Lilly, E. A., Ali, A., et al. (2013). Chemical screening identifies filastatin, a small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans adhesion, morphogenesis, and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13594–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305982110

Gao, M., Wang, H., and Zhu, L. (2016). Quercetin assists fluconazole to inhibit biofilm Formations of fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans in in vitro and in vivo antifungal managements of vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 40, 727–742. doi: 10.1159/000453134

Gimeno, C. J., Ljungdahl, P. O., Styles, C. A., and Fink, G. R. (1992). Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68, 1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90079-r

Gulati, M., and Nobile, C. J. (2016). Candida albicans biofilms: development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 18, 310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2016.01.002

Hornby, J. M., Jensen, E. C., Lisec, A. D., Tasto, J. J., Jahnke, B., Shoemaker, R., et al. (2001). Quorum sensing in the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans is mediated by farnesol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2982–2992. doi: 10.1128/aem.67.7.2982-2992.2001

Kebaara, B. W., Langford, M. L., Navarathna, D. H., Dumitru, R., Nickerson, K. W., and Atkin, A. L. (2008). Candida albicans Tup1 is involved in farnesol-mediatedinhibition of filamentous-growth induction. Eukaryot. Cell 7, 980–987. doi: 10.1128/EC.00357-07

Klotz, S. A., Drutz, D. J., and Zajic, J. E. (1985). Factors governing adherence of Candida species to plastic surfaces. Infect. Immun. 50, 97–101.

Kucharicová, S., Sharma, N., Spriet, I., Maertens, J., Van Dijck, P., and Lagrou, K. (2013). Activities of systematically administered echinocandins against in vivo mature Candida albicans biofilms developed in a rat subcutaneous model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 2365–2368. doi: 10.1128/aac.02288-12

Lan, W., Wan, S., Gu, W., Wang, H., and Zhou, S. (2014). Mechanisms behind the inhibition of lung adenocarcinoma cell by shikonin. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 70, 1459–1467. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0083-5

Lee, M. J., Kao, S. H., Hunag, J. E., Sheu, G. T., Yeh, C. W., Hseu, Y. C., et al. (2014). Shikonin time-dependently induced necrosis or apoptosis in gastric cancer cells via generation of reactive oxygen species. Chem. Biol. Interact. 211, 44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.01.008

Li, D. D., Zhao, L. X., Mylonakis, E., Hu, G. H., Zou, Y., Huang, T. K., et al. (2014). In vitro and in vivo activities of pterostilbene against Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 2344–2355. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01583-13

Liao, Z. B., Yan, Y., Dong, H. H., Zhu, Z. Y., Jiang, Y. Y., and Cao, Y. Y. (2016). Endogenous nitric oxide accumulation is involved in the antifungal activity of shikonin against Candida albicans. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 17:e88. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.87

Lindsay, A. K., Deveau, A., Piispanen, A. E., and Hogan, D. A. (2012). Farnesol and cyclic AMP signaling effects on the hypha-to-yeast transition in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 11, 1219–1225. doi: 10.1128/EC.00144-12

Liu, H., Kohler, J., and Fink, G. R. (1994). Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 266, 1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.7992058

Liu, N., Zhong, H., Tu, J., Jiang, Z., Jiang, Y., Jiang, Y., et al. (2018). Discovery of simplified sampangine derivatives as novel fungal biofilm inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 143, 1510–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.10.043

Lu, L., Qin, A., Huang, H., Zhou, P., Zhang, C., Liu, N., et al. (2011). Shikonin extracted from medicinal Chinese herbs exerts anti-inflammatory effect via proteasome inhibition. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 658, 242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.043

Luo, G., and Samaranayake, L. P. (2002). Candida glabrata, an emerging fungal pathogen, exhibits superior relative cell surface hydrophobicity and adhesion to denture acrylic surfaces compared with Candida albicans. APMIS 110, 601–610. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.1100902.x

Miao, H., Zhao, L. Y., Li, C. L., Shang, Q. H., Lu, H., Fu, Z. J., et al. (2012). Inhibitory effect of Shikonin on Candida albicans growth. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 35, 1956–1963. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00338

Mukherjee, P. K., Long, L. A., Kim, H. G., and Ghannoum, M. A. (2009). Amphotericin B lipid complex is efficacious in the treatment of Candida albicans biofilms using a model of catheter-associated Candida biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 33, 149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.030

Nam, K. N., Son, M. S., Park, J. H., and Lee, E. H. (2008). Shikonins attenuate microglial inflammatory responses by inhibition of ERK, Akt, and NF-kappaB: neuroprotective implications. Neuropharmacology 55, 819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.065

Navarathna, D. H., Hornby, J. M., Krishnan, N., Parkhurst, A., Duhamel, G. E., and Nickerson, K. W. (2007). Effect of farnesol on a mouse model of systemic candidiasis, determined by use of a DPP3 knockout mutant of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 75, 1609–1618. doi: 10.1128/iai.01182-06

Nett, J. E., Sanchez, H., Cain, M. T., Ross, K. M., and Andes, D. R. (2011). Interface of Candida albicans biofilm matrix-associated drug resistance and cell wall integrity regulation. Eukaryot. Cell 10, 1660–1669. doi: 10.1128/EC.05126-11

Nobile, C. J., Andes, D. R., Nett, J. E., Smith, F. J., Yue, F., Phan, Q. T., et al. (2006). Critical role of Bcr1-dependent adhesins in C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020063

Nobile, C. J., Fox, E. P., Nett, J. E., Sorrells, T. R., Mitrovich, Q. M., Hernday, A. D., et al. (2012). A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in candida albicans. Cell 148, 126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048

Nobile, C. J., and Mitchell, A. P. (2005). Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr. Biol. 15, 1150–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.047

Pfaller, M. A., and Diekema, D. J. (2007). Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 133–163. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00029-06

Polke, M., Leonhardt, I., Kurzai, O., and Jacobsen, I. D. (2018). Farnesolsignalling in Candida albicans - more than just communication. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 44, 230–243. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2017.1337711

Pompilio, A., Piccolomini, R., Picciani, C., D’Antonio, D., Savini, V., and Di Bonaventura, G. (2008). Factors associated with adherence to and biofilm formation on polystyrene by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: the role of cell surface hydrophobicity and motility. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 287, 41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01292.x

Quan, H., Cao, Y. Y., Xu, Z., Zhao, J. X., Gao, P. H., Qin, X., et al. (2006). Potent in vitro synergism of fluconazole and berberine chloride against clinical isolates of Candida albicans resistant to fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 1096–1099. doi: 10.1128/aac.50.3.1096-1099.2006

Ramage, G., Saville, S. P., Wickes, B. L., and Lopez-Ribot, J. L. (2002). Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm formation by farnesol, a quorum-sensing molecule. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 5459–5463. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.11.5459-5463.2002

Ramage, G., VandeWalle, K., Wickes, B. L., and Lopez-Ribot, J. L. (2001). Standardized method for in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2475–2479. doi: 10.1128/aac.45.9.2475-2479.2001

Samaranayake, Y. H., Wu, P. C., Samaranayake, L. P., and So, M. (1995). Relationship between the cell surface hydrophobicity and adherence of Candida krusei and Candida albicans to epithelial and denture acrylic surfaces. APMIS 103, 707–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01427.x

Sasaki, K., Abe, H., and Yoshizaki, F. (2002). In vitro antifungal activity of naphthoquinone derivatives. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 25, 669–670. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.669

Seneviratne, C. J., Jin, L., and Samaranayake, L. P. (2008). Biofilm lifestyle of Candida: a mini review. Oral Dis. 14, 582–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01424.x

Shirtliff, M. E., Krom, B. P., Meijering, R. A., Peters, B. M., Zhu, J., Scheper, M. A., et al. (2009). Farnesol-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 2392–2401. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01551-08

Sobel, J. D., Faro, S., Force, R. W., Foxman, B., Ledger, W. J., Nyirjesy, P. R., et al. (1998). Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 178, 203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)80001-x

Sundstrom, P. (2002). Adhesion in Candida spp. Cell Microbiol. 4, 461–469. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00206.x

Tobudic, S., Lassnigg, A., Kratzer, C., Graninger, W., and Presterl, E. (2010). Antifungal activity of amphotericin B, caspofungin and posaconazole on Candida albicans biofilms in intermediate and mature development phases. Mycoses 53, 208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01690.x

Tronchin, G., Pihet, M., Lopes-Bezerra, L. M., and Bouchara, J. P. (2008). Adherence mechanisms in human pathogenic fungi. Med. Mycol. 46, 749–772. doi: 10.1080/13693780802206435

Vassilios, P. P., Andreana, N. A., Elias, A. C., David, H., and Nicolaou, K. C. (1999). The chemistry and biology of alkannin, shikonin, and related naphthazarin natural products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 270–300. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3

Yano, J., and Fidel, P. L. Jr. (2011). Protocols for vaginal inoculation and sample collection in the experimental mouse model of candida vaginitis. J. Vis. Exp. 58:e3382. doi: 10.3791/3382

Keywords: Candida albicans, biofilms, shikonin, farnesol, hyphae

Citation: Yan Y, Tan F, Miao H, Wang H and Cao Y (2019) Effect of Shikonin Against Candida albicans Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 10:1085. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01085

Received: 25 August 2018; Accepted: 30 April 2019;

Published: 14 May 2019.

Edited by:

Jack Wong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Rohitashw Kumar, University at Buffalo, United StatesMelyssa Negri, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Brazil

Copyright © 2019 Yan, Tan, Miao, Wang and Cao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: YingYing Cao, caoyingying608@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yu Yan1†

Yu Yan1† YingYing Cao

YingYing Cao