- Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese, Policlinico “Santa Maria alle Scotte”, Siena, Italy

Multiple myeloma survival has significantly improved in the latest years due to a broad spectrum of novel agents available for treatment. The introduction of thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide together with autologous stem-cell transplantation has considerably increased complete remission rate and progression-free survival resulting ultimately in prolonged survival in myeloma patients. Moreover, novel strategies of treatment such as consolidation and maintenance are being used to further implement responses. Finally, a number of new drugs such as carfilzomib and pomalidomide are already in clinical practice, making the future of myeloma patients brighter.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell malignancy characterized by clonal proliferation of plasma cells in the bone marrow microenvironment and associated organ damage (CRAB = increased calcium, renal insufficiency, anemia, bone lesions) (1). The organ damage is due to a monoclonal protein produced in the blood or urine. It represents about 10% of hematological cancers and 1% of all cancers. Median age at diagnosis is 70 years. In the last decades, we experienced a great improvement in myeloma survival both in young and old patients (2, 3). In fact, 5-year relative survival increased from 28.8 to 34.7% and 10-year relative survival increased from 11.1 to 17.4% between 1990–1992 and 2002–2004. A more evident increase was seen in the age group younger than 50 years, leading to 5- and 10-year relative survival of 56 and 41% in 2002–2004, and in the age group 50–59 years, leading to 5- and 10-year relative survival of 48 and 28% in 2002–2004. By contrast, only moderate improvement was seen in the age group 60–69 years, and no substantial improvement was achieved among older patients (3). The clinical progresses are related to the introduction of novel agents (bortezomib, thalidomide, lenalidomide) and especially for young patients, to autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT). These approaches resulted in an increased rate of complete response (CR) that translated into prolonged survival and improved quality of life. Additionally, peculiar extra medullary localizations of MM seemed to benefit from novel agents therapy (4). Nonetheless, a better understanding of plasma cell biology and myeloma pathways has resulted in the identification of novel targets for therapy. New agents deriving from already approved and active agents (such as second- and third generation proteasome inhibitors, thalidomide, lenalidomide) have been developed and also new drugs with novel mechanisms of action are under investigation in clinical trials.

Although advancements have been outstanding in the field of myeloma, there is still a small group of patients (10–15%) that has a dismal prognosis, i.e., del 17p and t(4;14) patients, in which novel therapeutic approaches are urgently warranted (5–7).

Initial Treatment of Transplant Eligible Myeloma Patients

Today patients younger than 65 years are usually eligible for ASCT. As induction treatment, three or four cycles of therapy are usually given and less than six cycles are recommended (8).

Induction therapy is given to reduce tumor burden before stem-cell harvest, and drugs that can compromise hematopoietic stem-cell collection should be avoided (alkylating agents) (8).

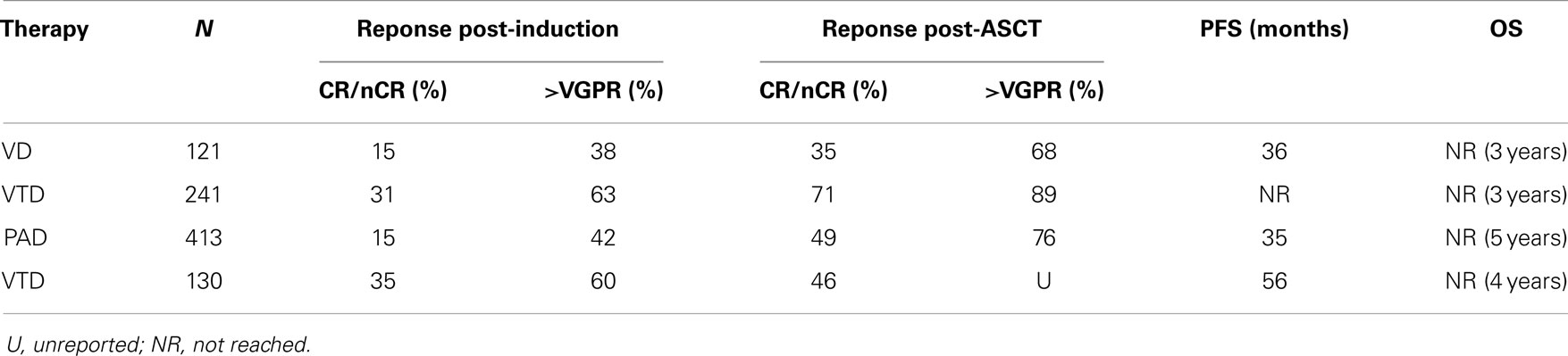

On the basis of the available data from phase II studies, three-drug combination regimens are considered as the standard of care for use as induction therapy prior to ASCT. Thalidomide was the first novel agent compared with vincristine, adriamycin, dexamethasone (VAD) either in combination with dexamethasone or with dexamethasone and doxorubicin (TAD), the latter with a little benefit (9). Data of the most commonly used agents in phase III trials are summarized in Table 1. The most effective combinations include proteasome inhibitors plus either thalidomide, lenalidomide, or chemotherapy. Bortezomib in combination with dexamethasone (VD) was compared with VAD (10) with induction of CR/near-CR in 15 vs. 6% and overall response rates 79 vs. 63%, respectively. Even after ASCT, responses were confirmed superior for VD: CR/nCR: 35 vs. 18%. Median progression-free survivals (PFS) were 36 vs. 30 months with VD vs. VAD, respectively, yet survival that was not superior in the VD arms maybe due to effective salvage regimens at the time of relapse.

The combination of bortezomib–thalidomide–dexamethasone (VTD) has proved to be superior to thalidomide–dexamethasone (TD) as induction therapy before ASCT resulting in a 3-year PFS of 68% for the VTD arm vs. 56% for the TD arm (11). VTD was also superior in a Spanish study associated with thalidomide maintenance (12). The addiction of doxorubicin to bortezomib–dexamethasone (PAD) was superior to VAD followed by ASCT and thalidomide maintenance, with a median PFS of 35 vs. 28 months, respectively (13).

The association of bortezomib as induction therapy with other one or two drugs showed a superior efficacy in terms of responses, but none showed so far superiority in terms of overall survival (OS). Phase II trials have showed that the addition of cyclophosphamide (VCD) or lenalidomide (VRD) can be feasible with at least partial remission (PR) in 97 and 100% of patients, respectively (14, 15). In another phase II study, the four drugs combination with bortezomib–dexamethasone–cyclophosphamide–lenalidomide (VCDR) appeared to be a good induction option (16) with a CR rate of 25% and a very good partial response (VGPR) rate of at least 58%.

The novel proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib was also tested in phase II studies in newly diagnosed patients: in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (CRd) showed outstanding responses with CR/nCR in 67% (17). In another study, Carfilzomib–thalidomide–dexamethasone was given as pre-transplant induction and post-transplant consolidation and led to 18% CR and 91% >PR (18).

Consolidation/Maintenance

Therapy consolidation (usually two cycles after ASCT to increase responses) and maintenance (continuous therapy until progression) are being explored to improve outcome after ASCT as an alternative to perform a second autotransplant with the idea to achieve the same efficacy but with less toxicity. In one study, VTD consolidation increased CR from 15 to 49% in patients who had previously achieved VGPR after double ASCT (19). Molecular remissions by allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (AS-PCR) following VTD treatment had a better outcome: the PFS at 42 months for patients with a low tumor load was 100 vs. 57% for patients with a higher tumor load after VTD. Another study confirmed these findings (20). Two cycles of consolidation therapy with TD or VTD were given after the second ASCT. In the TD arm, consolidation improved the CR rate from 40 to 47%. In the VTD arm, the CR rate increased from 49 to 61%. Several studies are ongoing to better evaluate the role of consolidation therapy.

Maintenance has been explored first with thalidomide and subsequently with lenalidomide (21–23). Six phase III studies have shown a benefit for thalidomide in terms of response and PFS, but OS was improved only in two of these trials (24–28). Yet, grade 3–4 polyneuropathy was a major concern (7–19%), inducing 52% of median discontinuation rate. Lenalidomide is currently considered as the best candidate for use as maintenance therapy because of a safer profile. Results from two randomized trials evaluating lenalidomide maintenance following ASCT have recently been published. Although an advantage in progression-free survival was seen in both trials, a benefit in OS for patients receiving maintenance therapy was observed only in the trial published by McCarthy et al. (23). However, this benefit was limited to those patients who had not achieved a CR on their previous treatment strategy. Questions have been raised about the need of a maintenance therapy for every myeloma patient (29, 30). In addition to carefully consider the risk–benefit ratio for a patient during maintenance therapy (increase of second malignancies), patient’s quality of life and treatment cost effectiveness should be also evaluated. These findings highlight the importance of identifying the optimal duration of therapy and risk factors for this complication.

Initial Treatment of Non-Transplant Eligible Myeloma Patients

About two-thirds of MM patients are more than 65 years old at the time of the first diagnosis. Therefore, the majority of patients are usually not eligible for high-dose therapy followed by ASCT. Especially in the elderly, the treatment must be individualized because of their vulnerability that can complicate both the presentation and management of MM (31, 32). As such, it is mandatory to take into consideration the “biological” age of the patient not only the chronologic age, including the evaluation of both the performance status by score such as Karnofsky scale and the comorbidities by geriatric score (33). Age-related organ functions and metabolic changes can contribute to the poor tolerability of treatments as well as to increased treatment-related adverse events. Due to these toxicities, dose adjustments are often required with a consequent reduction of dose intensity that can lead to the poorer outcome observed frequently in elderly patients. The prolongation of PFS and OS must remain as initial aims in the management of old MM patient, although the quality of life should ultimately prevail in the oldest and fragile ones.

Induction Therapy: What is the Best Treatment?

Achieving at least a VGPR has been demonstrated to be related to an improvement of the long-term outcome also in the elderly patients (34). Standard frontline treatment for elderly patients has been for long time the combination of the oral alkylating agent melphalan with prednisone (MP). This schedule is well tolerated even in frail patients and can be administered as outpatient regimen with maintenance of a good quality of life but the overall response rate obtained is dismal. The introduction of novel agents, such as thalidomide, lenalidomide, and bortezomib, has led to better responses also in this setting of patients. Since the CR is an independent predictor of longer PFS and OS regardless of age and International Staging System (ISS), a novel agent is recommended in the induction therapy.

Six randomized studies have compared the efficacy and safety of the standard MP regimen to the new combination of MP plus thalidomide (MPT) (35–41). These trials reported an evident improvement of the overall response rate and the PFS associated with the MPT regimen with respect to MP, but the advantage in OS is unclear. There are two meta-analyses of these data that confirmed a significant improvement in PFS (5.4 months) and a “trend” toward significant improvement in OS (6.6 months) when thalidomide is added to MP as a frontline treatment in elderly patients (42). In addition, the improvement seems to be less pronounced in patients aged 75 years and the optimal dose of thalidomide is not established as most of the clinicians adapted the dose according to patient’s status and occurrence of side effects or toxicity. At least 75% of the grade 3–4 toxicities occurred during the first 6 months of treatment. Neuropathy, deep-vein thrombosis, and dermatological toxicity were the most frequent thalidomide-related adverse events, while hematologic toxicities seemed to be related to melphalan doses.

Cyclophosphamide is another alkylating agent that can be associated with thalidomide and this association achieved an improvement in overall response rate compared to the standard MP (64 vs. 33% respectively), but in terms of PSF and OS there are no differences between the two regimens (43).

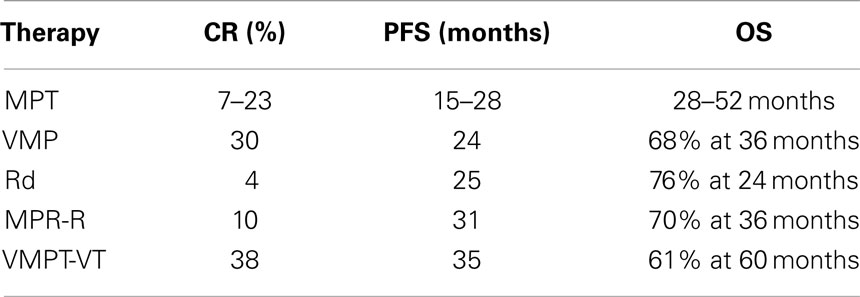

A randomized phase III study compared bortezomib–melphalan–prednisone (VMP) to MP also in the elderly. VMP significantly increased the CR rate (from 4 to 30%), PFS (from 16 to 23 months), and OS (from 43 to 56 months) with respect to MP (44). Subsequently, a reduced bortezomib schedule (from twice- to once-weekly administration) was shown to be better tolerated without affecting the outcome (45). Today, both MPT and VMP are considered the standard therapies for elderly patients (Table 2).

More recently, a phase III trial compared lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone (RD) to lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) in newly diagnosed MM patients. Rd induced a significantly longer 1-year OS and a lower toxicity compared to RD (46). The three-drugs regimen melphalan–prednisone–lenalidomide followed by lenalidomide maintenance (MPR-R) was lately compared to MPR and MP in a phase III trial. In this study, MPR-R significantly reduced the risk of progression with respect to MPR and MP. The CR rate was 10% for MPR-R and 3% for both MPR and MP. MPR-R also significantly prolonged median PFS (31 vs. 14 vs. 13 months, respectively) (47).

Bortezomib plus thalidomide (VT) maintenance was assessed in two trials (48, 49). In both studies, PFS was improved although OS only in one.

Conclusion

Many new treatments are now available for MM patients both transplant-related and non-transplant-related and a continuous improvement in disease free and OS is expected with the advent of the newest drugs. If prolongation of OS should be always the first aim of treatment in the management of elderly and fragile patients, quality of life should be carefully evaluated.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. Blood (2008) 11:2962–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-078022

2. Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Recent major improvement in long-term survival of younger patients with multiple myeloma. Blood (2008) 111:2521–6. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-08-104984

3. Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood (2008) 111:2516–20. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129

4. Gozzetti A, Cerase A, Lotti F, Rossi D, Palumbo A, Petrucci MT, et al. GIMEMA (Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto) myeloma working party extramedullary intracranial localizations of multiple myeloma and treatment with novel agents: a retrospective survey of 50 patients. Cancer (2012) 118:1574–84. doi:10.1002/cncr.26447

5. Ocio EM, Richardson PG, Rajkumar SV, Palumbo A, Mateos MV, Orlowski R, et al. New drugs and novel mechanisms of action in multiple myeloma 2013: a report from the International Myeloma Working group (IMWG). Leukemia (2014) 28:525–42. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.350

6. Fonseca R, Blood E, Rue M, Harrington D, Oken MM, Kyle RA, et al. Clinical and biologic implications of recurrent genomic aberrations in myeloma. Blood (2003) 101:4569–75. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-10-3017

7. Gozzetti A, Le Beau MM. Fluorescence in situ hybridization: uses and limitations. Semin Hematol (2000) 37:320–33. doi:10.1053/shem.2000.16443

8. Stewart AK, Richardson PG, San-Miguel JF. How I treat multiple myeloma in younger patients. Blood (2009) 114:5436–43. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-07-204651

9. Moreau P, Avet-Loiseau H, Harousseau JL, Attal M. Current trends in autologous stem-cell transplantation for myeloma in the era of novel therapies. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29:1898–906. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5878

10. Harousseau JL, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H, Marit G, Caillot D, Mohty M, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the IFM 2005–01 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol (2010) 28:4621–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.9158

11. Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, Petrucci MT, Pantani L, Galli M, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 3 study. Lancet (2010) 376:2075–85. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61424-9

12. Rosiñol L, Oriol A, Teruel AI, Hernández D, López-Jiménez J, de la Rubia J, et al. Superiority of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD) as induction pretransplantation therapy in multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 3 PETHEMA/GEM study. Blood (2012) 120:1589–96. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-02-408922

13. Sonneveld P, Schmidt-Wolf IGH, van der Holt B, El Jarari L, Bertsch U, Salwender H, et al. Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol (2012) 30:2946–55. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6820

14. Reeder CB, Reece DE, Kukreti V, Chen C, Trudel S, Laumann K. Once versus twice weekly bortezomib induction therapy with CyBordD in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood (2012) 115:3416–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-02-271676

15. Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, Jakubowiak AJ, Jagannath S, Raje NS, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood (2010) 116:679–86. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-02-268862

16. Kumar S, Flinn I, Richardson PG, Hari P, Callander N, Noga SJ. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood (2012) 119:4375–82. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-11-390658

17. Jakubowiak AJ, Dytfeld D, Griffith KA, Lebovic D, Vesole DH, Jagannath S, et al. A phase 1/2 study of carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone as a frontline treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood (2012) 120:1801–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-04-422683

18. Sonneveld P, Asselbergs E, Zweegman S, Van der Holt B, Kersten MJ, Vellenga E, et al. Carfilzomib combined with thalidomide and dexamethasone (CTD) is a highly effective induction and consolidation treatment in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma who are transplant candidates. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program (2012) 120:333.

19. Ladetto M, Pagliano G, Ferrero S, Cavallo F, Drandi D, Santo L, et al. Major tumor shrinking and persistent molecular remissions after consolidation with bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone in patients with autografted myeloma. J Clin Oncol (2010) 28:2077–84. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7172

20. Cavo M, Pantani L, Petrucci MT, Patriarca F, Zamagni E, Donnarumma D. Bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone is superior to thalidomide-dexamethasone as consolidation therapy following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood (2012) 120:9–19. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-02-408898

21. Morgan GJ, Gregory WM, Davies FE, Bell SE, Szubert AJ, Brown JM, et al. The role of maintenance thalidomide therapy in multiple myeloma: MRC Myeloma IX results and meta-analysis. Blood (2012) 119:7–15. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-06-357038

22. Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, Caillot D, Moreau P, Facon T, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med (2012) 366:1782–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114138

23. McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, Hurd DD, Hassoun H, Richardson PG, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med (2012) 366:1770–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114083

24. Lokhorst HM, van der Holt B, Zweegman S, Vellenga E, Croockewit S, van Oers MH, et al. A randomized phase 3 study on the effect of thalidomide combined with adriamycin, dexamethasone, and high-dose melphalan, followed by thalidomide maintenance in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood (2010) 115:1113–20. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-05-222539

25. Attal M, Harousseau JL, Leyvraz S, Doyen C, Hulin C, Benboubker L, et al. Maintenance therapy with thalidomide improves survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood (2006) 108:3289–94. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-05-022962

26. Barlogie B, Attal M, Crowley J, van Rhee F, Szymonifka J, Moreau P. Long-term follow-up of autotransplantation trials for multiple myeloma: update of protocols conducted by the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome, Southwest Oncology Group, and University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. J Clin Oncol (2010) 28:1209–14. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6081

27. Spencer A, Prince HM, Roberts AW, Prosser IW, Bradstock KF, Coyle L, et al. Consolidation therapy with low-dose thalidomide and prednisolone prolongs the survival of multiple myeloma patients undergoing a single autologous stem-cell transplantation procedure. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27:1788–93. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8573

28. Stewart AK, Trudel S, Bahlis NJ, White D, Sabry W, Belch A, et al. A randomized phase III trial of thalidomide and prednisone as maintenance therapy following autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with multiple myeloma (MM) with a quality of life assessment: NCIC CTG MY.10 Trial. Blood (2013) 121:1517–30. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-09-451872

29. Rajkumar SV. Lenalidomide maintenance – perils of a premature denouement. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2012) 9:372–4. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.100

30. Gozzetti A, Defina M. Bocchia lenalidomide maintenance in myeloma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2012) 9:605. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.100-c1

31. Mateos MV, San Miguel JF. How should we treat newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patient? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program (2013) 2013:488–95. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.488

32. Cerrato C, Palumbo A. Initial treatment of nontransplant patients with multiple myeloma. Semin Oncol (2013) 40:577–84. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.07.003

33. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis (1987) 40:373–83. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

34. Gay F, Larocca A, Wijermans P, Cavallo F, Rossi D, Schaafsma R, et al. Complete response correlates with long-term progression-free and overall survival in elderly myeloma treated with novel agents: analysis of 1175 patients. Blood (2011) 117:3025–31. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-09-307645

35. Facon T, Mary JY, Hulin C, Benboubker L, Attal M, Pegourie B, et al. Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide versus melphalan and prednisone alone or reduced-intensity autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients with multiple myeloma (IFM 99-06): a randomized trial. Lancet (2007) 370:1209–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61537-2

36. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Caravita T, Merla E, Capparella V, Callea V, et al. Oral melphalan and prednisone chemotherapy plus thalidomide compared with melphalan and prednisone alone in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2006) 367:825–31. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68338-4

37. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Liberati AM, Caravita T, Falcone A, Callea V. Oral melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: updated results of a randomized controlled trial. Blood (2008) 112:3107–14. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-04-149427

38. Wijermans P, Schaafsma M, Termorshuizen F, Ammerlaan R, Wittebol S, Sinnige H, et al. Phase III study of the value of thalidomide added to melphalan plus prednisone in elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the HOVON 49 Study. J Clin Oncol (2010) 28:3160–6. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1610

39. Hulin C, Facon T, Rodon P, Pegourie B, Benboubker L, Doyen C, et al. Efficacy of melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide in patients older than 75 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: IFM 01/01 trial. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27:3664–70. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0948

40. Waage A, Gimsing P, Fayers P, Abildgaard N, Ahlberg L, Björkstrand B, et al. Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide or placebo in elderly patients with multiple myeloma. Blood (2010) 116:1405–12. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-08-237974

41. Beksac M, Haznedar R, Firatli-Tuglular T, Ozdogu H, Aydogdu I, Konuk N. Addition of thalidomide to oral melphalan/prednisone in patients with multiple myeloma not eligible for transplantation: results of a randomized trial from the Turkish Myeloma Study Group. Eur J Haematol (2011) 86:16–22. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01524.x

42. Fayers PM, Palumbo A, Hulin C, Waage A, Wijermans P, Beksaç M, et al. Thalidomide for previously untreated elderly patients with multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of 1685 individual patient data from 6 randomized clinical trials. Blood (2011) 118:1239–47. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-03-341669

43. Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Gregory WM, Russell NH, Bell SE, Szubert AJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (CTD) as initial therapy for patients with multiple myeloma unsuitable for autologous transplantation. Blood (2011) 118:1231–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-338665

44. San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med (2008) 359:906–17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801479

45. Bringhen S, Larocca A, Rossi D, Cavalli M, Genuardi M, Ria R, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly bortezomib in multiple myeloma patients. Blood (2010) 116:4745–53. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-07-294983

46. Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, Fonseca R, Vesole DH, Williams ME, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol (2010) 11:29–37. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0

47. Palumbo A, Hajek R, Delforge M, Kropff M, Petrucci MT, Catalano J, et al. Continuous lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med (2012) 366:1759–69. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1112704

48. Mateos MV, Oriol A, Martínez-López J, Gutiérrez N, Teruel AI, de Paz R, et al. Bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone versus bortezomib, thalidomide, and prednisone as induction therapy followed by maintenance treatment with bortezomib and thalidomide versus bortezomib and prednisone in elderly patients with untreated multiple myeloma: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol (2010) 11:934–41. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70187-X

49. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Larocca A, Rossi D, Di Raimondo F, Magarotto V. Bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide followed by maintenance with bortezomib-thalidomide compared with bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma: updated follow-up and improved survival. J Clin Oncol (2014) 32:634–40. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.52.0023

Keywords: multiple myeloma, young, elderly, bortezomib, IMID’s, new therapies

Citation: Gozzetti A, Candi V, Papini G and Bocchia M (2014) Therapeutic advancements in multiple myeloma. Front. Oncol. 4:241. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00241

Received: 06 June 2014; Accepted: 20 August 2014;

Published online: 04 September 2014.

Edited by:

Varsha Gandhi, MD Anderson Cancer Center, USAReviewed by:

Christine Marie Stellrecht, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, USAHarold J. Olney, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Canada

Copyright: © 2014 Gozzetti, Candi, Papini and Bocchia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessandro Gozzetti, Division of Hematology, Policlinico “Santa Maria alle Scotte”, Viale Bracci 16, Siena 53100, Italy e-mail: gozzetti@unisi.it

Alessandro Gozzetti

Alessandro Gozzetti Veronica Candi

Veronica Candi Giulia Papini

Giulia Papini