Published online Feb 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1305

Revised: December 7, 2007

Published online: February 28, 2008

We present two cases of windsock deformity; both were rare in location and one had a rare associated anomaly. In the first case, the windsock was observed in the fourth part of duodenum, causing partial intestinal obstruction. In the second case, the windsock was located in the third part of the duodenum.

- Citation: Melek M, Edirne YE. Two cases of duodenal obstruction due to a congenital web. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(8): 1305-1307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i8/1305.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1305

Windsock deformity (WD) is a rare anomaly. Fewer than 100 cases of WD have been reported[1–3]. The second part of the duodenum is the most common site of WD[1]. Associated anomalies, such as intestinal malrotation and a preduodenal portal vein, are well known. Presentation of a fenestrated duodenal web with acute pancreatitis has also been reported[4]. We report two cases of windsock deformity; both were rare in location and one had a rare associated anomaly.

A 19 mo-old boy was admitted to the Clinic of Pediatric Surgery at the University of Yuzuncu Yil, Van, Turkey, with abdominal distention and vomiting. He had tolerated only milk and fluids since birth. The parents were children of first-degree relatives and had six living children. Two brothers of the case died immediately after birth and one sister died at an age of eight months, of unknown causes.

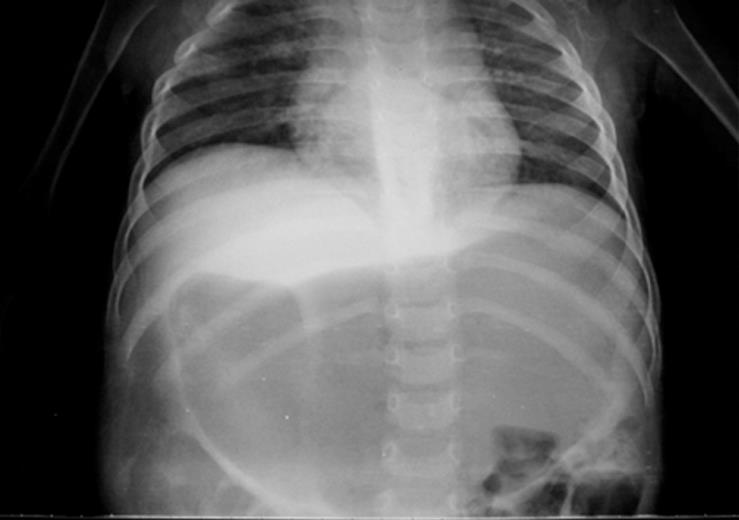

On physical examination, epigastric distention was present, but no mass or organomegaly was palpated. Abdominal X-ray on admission showed a dilated stomach (Figure 1). An upper gastrointestinal contrast study demonstrated an axial rotation appearance of the stomach. The transition time of small intestine content was evaluated as normal.

At laparotomy, the stomach was significantly dilated and the pylorus seemed to be completely erased at the junction. The wall thicknesses of the duodenum at the first and second parts were increased and similar to the thickness of the antral wall. The jejunoileal walls were thinner than normal and were empty at the distal end. Attempts were made to pass a nasogastric catheter to the jejunum, but the catheter could not go beyond the fourth part of the duodenum. Normal saline, given from the nasogastric catheter, could not pass freely to the distal end, and caused distention of the proximal duodenum. A longitudinal incision was made from the antimesenteric border at the transitional zone. A web, which caused an obstruction just before the Treitz ligament, was observed. In the centre of the web was a hole with a diameter of about 3-4 mm. The web was excised circumferentially. The vertical incision was closed. The nasogastric catheter was taken out on the seventh postoperative day. Abdominal X-rays at early and late postoperative days were normal. A contrast study in the fourth week after the operation revealed a normal duodenal appearance.

A 5 mo-old girl presented to the same institution with abdominal distention and bilious vomiting, mostly seen after meals, for three months. At physical examination, she had mild epigastric distention. There was no mass or organomegaly in the abdomen on palpation. Hematologic parameters and biochemical laboratory findings were normal.

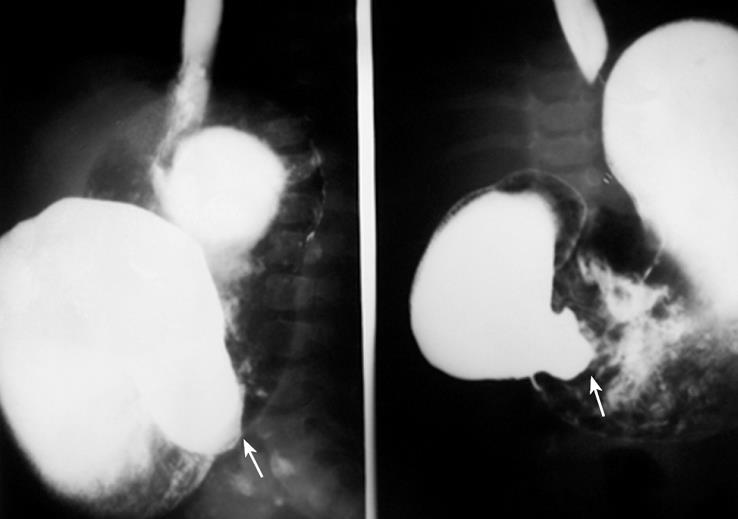

An upper gastrointestinal contrast study pre-operatively showed a dilated stomach. The duodenum was dilated in the first and second parts, but the third part was narrow (Figure 2). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a normal liver size with a hyperechogenic lesion of 30 mm × 25 mm × 20 mm in size, compatible with hemangioma at the caudate lobe.

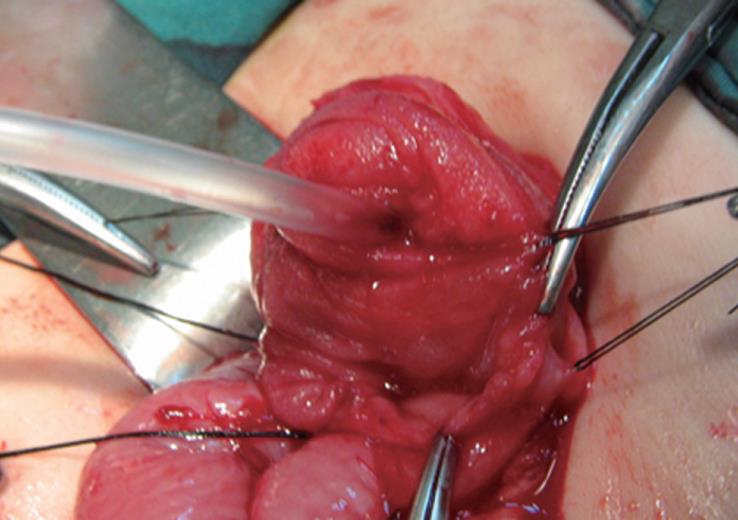

At laparotomy the duodenum was dilated and the wall thickness was increased. Duodenotomy was performed longitudinally on the antimesenteric side after palpation of a membranous structure in the lumen. A web was seen and a windsock deformity was diagnosed. The opening in the middle of the web was catheterized with a 12 CH catheter (Figure 3). The web was excised circumferentially and the enterotomy was closed.

During exploration, a lesion localized in the caudate lobe of the liver 25 mm × 30 mm in size, elastic in nature and compatible with hemangioma was detected. Neither biopsy, nor excision was performed. The nasogastric catheter was pulled out postoperatively at sixth day. Oral feeding was tolerated well and she was discharged from the hospital on the 12th postoperative day.

Only 100 cases of WD have been reported in the literature[1–3]. The second part of the duodenum is the most common site, representing 85% to 90% of all WD cases. The third and fourth parts of the duodenum represent 20% and 10% of WD cases, respectively[15].

The WD in our first case was in the fourth part of the duodenum, which is a very rare location. The duodenum undergoes a solid phase; between the eighth and tenth week of gestation, the duodenal lumen is re-established by the gathering of vacuoles, and re-canalization occurs. Insults during this crucial period of development are believed to result in a failure of re-canalization and consequent atresia, stenosis and webs[56]. The resultant obstruction causes dilatation in the proximal duodenum and stomach, as well as hypertrophy and distention of pylorus[5].

Abdominal distention and vomiting were common complaints in each of our cases. Our first case was followed up by a pediatrician with diagnoses of constipation and growth failure. The great majority of individuals with WD are asymptomatic. A significant proportion of patients have a later onset of symptoms, and in some, the diagnosis is delayed until adulthood[7]. Clinical presentation may be characterized by nonspecific abdominal symptoms. Abdominal discomfort is usually located in the epigastria, right upper abdomen or umbilical area, and is made worse or brought on by eating and relieved by vomiting, belching or assuming a certain posture[15].

WD can be an incidental finding of upper gastrointestinal barium examination. In the second case, a pre-operative upper gastrointestinal study revealed the intraduodenal web. One of the most important features of duodenal diverticulum is the retention of barium in the sac. Barium retention for 6 or more hours is diagnostic[13].

Associated anomalies, such as intestinal malrotation and a preduodenal portal vein, are well recognized. Pancreatitis has also been reported in individuals with intraluminal duodenal diverticula[45]. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome is a very rare condition in childhood, most frequently resulting in duodenal obstruction in the adult population[12]. Bleeding from ulcers at the diverticulum[8], obstruction from gallstones[9] and marbles[3], as well as cholangitis[10] have been described. Hepatic hemangioma is an unusual finding in the pediatric population and is more common in older children and adolescents than in neonates and infants[111]. We discovered, incidentally, the hemangioma during US for the diagnosis of intestinal pathology.

Duodenotomy with web excision was performed in both of our cases. Two basic options for the repair of duodenal obstruction secondary to a web or atresia are presented: duodenoduodenostomy and duodenotomy with excision of the web. The web should be defined with the aid of a tube trough in the stomach, and the ampulla of Vater should be carefully identified prior to excision. The advent of improved pediatric flexible fiberoptic endoscopes and fiberoptic laser technology makes endoscopic ablation of duodenal webs and windsocks in the newborn possible[59].

We aimed to present two cases of WD showing rare locations in the fourth and third part of the duodenum from the same institution.

| 1. | Mahajan SK. Duodenal diverticulum: Review of Literature. Indian J Surg. 2004;66:1450-1453. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Knoefel WT, Rattner DW. Duodenal diverticula and duodenal tumours. Oxford Text Book of Surgery. New York: Oxford University Press 1994; 943-946. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Afridi SA, Fichtenbaum CJ, Taubin H. Review of duodenal diverticula. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:935-938. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Alizai NK, Puntis JW, Stringer MD. Duodenal web presenting with acute pancreatitis. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1255-1256. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Tandler J. Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Menschlichen Duodenums im frühen Embryonal Stadium. Gegenhaur Morphol Jahrbuch. 1900;29:187. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Klein P, Anetsberger R, Stangl R, Hummer HP. Congenital duodenal stenosis in adulthood. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1994;379:54-57. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Yoon CH, Goo HW, Kim EA, Kim KS, Pi SY. Sonographic windsock sign of a duodenal web. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:856-857. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Kay GA, Lobe TE, Custer MD, Hollabaugh RS. Endoscopic laser ablation of obstructing congenital duodenal webs in the newborn: a case report of limited success with criteria for patient selection. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:279-281. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Spigland N, Yazbeck S. Complications associated with surgical treatment of congenital intrinsic duodenal obstruction. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:1127-1130. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Regier TS, Ramji FG. Pediatric hepatic hemangioma. Radiographics. 2004;24:1719-1724. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Unal B, Aktas A, Kemal G, Bilgili Y, Guliter S, Daphan C, Aydinuraz K. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: CT and ultrasonography findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11:90-95. [Cited in This Article: ] |