Published online Jul 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3504

Revised: June 15, 2009

Accepted: June 22, 2009

Published online: July 28, 2009

AIM: To assess the combined effect of disease phenotype, smoking and medical therapy [steroid, azathioprine (AZA), AZA/biological therapy] on the probability of disease behavior change in a Caucasian cohort of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD).

METHODS: Three hundred and forty well-characterized, unrelated, consecutive CD patients were analyzed (M/F: 155/185, duration: 9.4 ± 7.5 years) with a complete clinical follow-up. Medical records including disease phenotype according to the Montreal classification, extraintestinal manifestations, use of medications and surgical events were analyzed retrospectively. Patients were interviewed on their smoking habits at the time of diagnosis and during the regular follow-up visits.

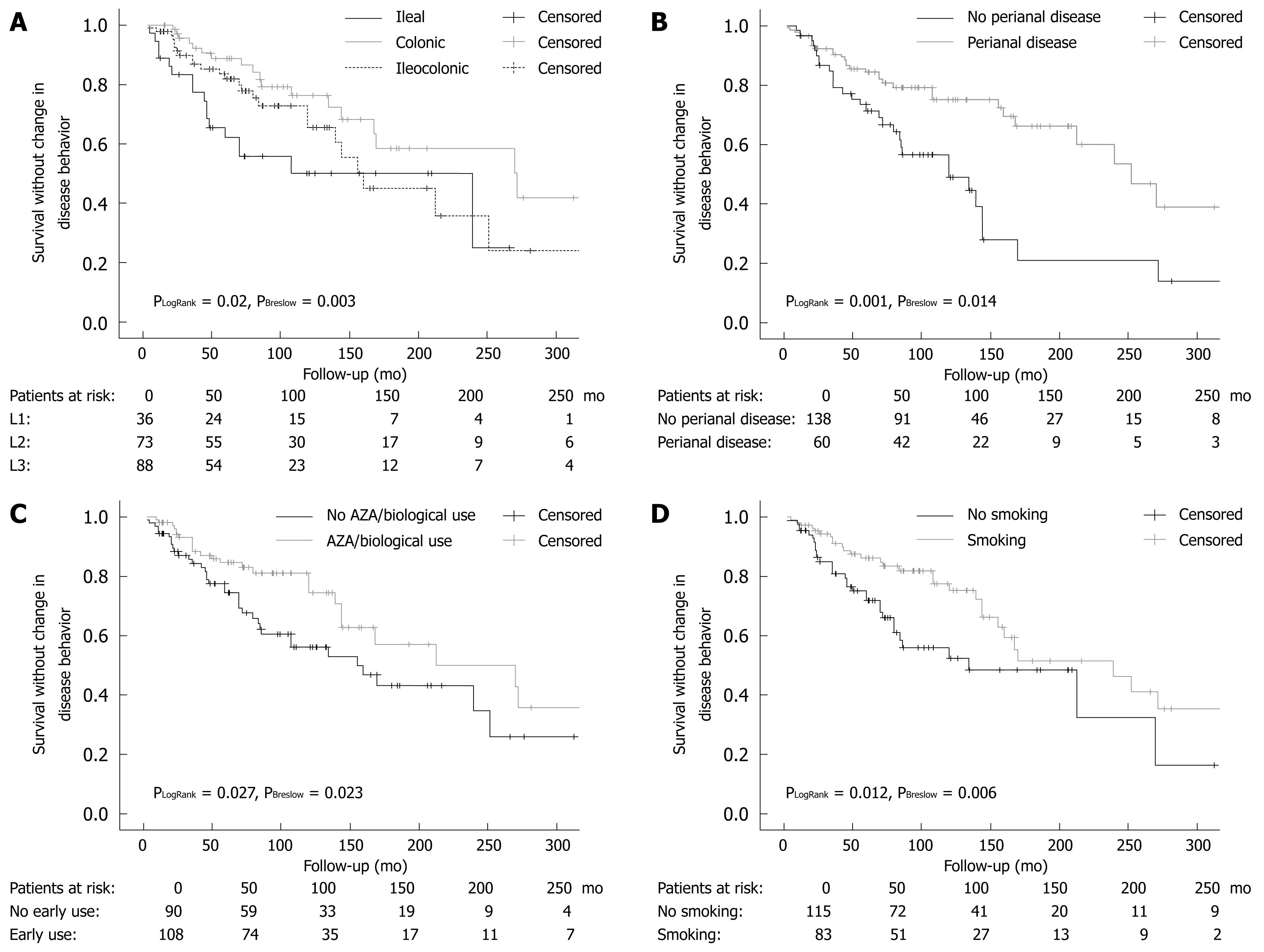

RESULTS: A change in disease behavior was observed in 30.8% of patients with an initially non-stricturing, non-penetrating disease behavior after a mean disease duration of 9.0 ± 7.2 years. In a logistic regression analysis corrected for disease duration, perianal disease, smoking, steroid use, early AZA or AZA/biological therapy use were independent predictors of disease behavior change. In a subsequent Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and a proportional Cox regression analysis, disease location (P = 0.001), presence of perianal disease (P < 0.001), prior steroid use (P = 0.006), early AZA (P = 0.005) or AZA/biological therapy (P = 0.002), or smoking (P = 0.032) were independent predictors of disease behavior change.

CONCLUSION: Our data suggest that perianal disease, small bowel disease, smoking, prior steroid use, early AZA or AZA/biological therapy are all predictors of disease behavior change in CD patients.

- Citation: Lakatos PL, Czegledi Z, Szamosi T, Banai J, David G, Zsigmond F, Pandur T, Erdelyi Z, Gemela O, Papp J, Lakatos L. Perianal disease, small bowel disease, smoking, prior steroid or early azathioprine/biological therapy are predictors of disease behavior change in patients with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(28): 3504-3510

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i28/3504.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3504

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a multifactorial disease with probable genetic heterogeneity[1]. In addition, several environmental risk factors (e.g. diet, smoking, measles or appendectomy) may contribute to its pathogenesis. During the past decades, the incidence pattern of both forms has significantly changed[2], showing some common but also quite distinct characteristics for the two disorders.

Phenotypic classification of Crohn’s disease (CD) plays an important role in determining treatment and may assist in predicting the likely clinical course of disease[3]. In 2005, the Montreal revision of the Vienna classification system was introduced[4]. Although the broad categories for CD classification remained the same, changes were made within each category. Upper gastrointestinal disease can now exist independently of, or together with, disease present at more distal locations. Finally, perianal disease, which occurs independently of small bowel fistulae, is no longer classified as penetrating disease. Instead, a perianal modifier has been introduced, which may coexist with any disease behavior.

Using the Vienna classification system, it has been shown in clinic-based cohorts that there can be a significant change in disease behavior over time, whereas disease location remains relatively stable[35]. An association between the presence of perianal disease and internal fistulation (OR: 2.6-4.6) was reported earlier by Sachar et al[6] in patients with colonic disease. Most recently, Australian authors[3] have shown that although > 70% of CD patients had inflammatory disease at diagnosis, the proportion of patients with complicated disease increased over time. Progression to complicated disease was more rapid in those with small bowel than colonic disease location (P < 0.001), with perianal disease being also a significant predictor of change in CD behavior (HR: 1.62, P < 0.001). Similarly, small bowel location and stricturing disease were predictors for surgery in a long-term follow-up study[7]. Finally, perianal lesions, the need for steroids to treat the first flare-up and ileo-colonic location, but not an age below 40 years were confirmed as predictive markers for developing disabling disease (according to the predefined criteria) at 5 years[8]. In the same study, stricturing behavior (HR: 2.11, 95% CI: 1.39-3.20) and weight loss (> 5 kg) (HR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.14-2.45) at diagnosis were independently associated with the time to development of severe disease.

A further environmental factor which may be of importance in determining change in disease behavior is smoking. In CD, smoking was reported to be associated with disease location: most, but not all, studies report a higher prevalence of ileal disease and a lower prevalence of colonic involvement in smokers[910]. A recent review[10] and previous data have demonstrated that smoking, when measured up to the time-point of disease behavior classification, was more frequently associated with complicated disease and penetrating intestinal complications[91112], a greater likelihood of progression to complicated disease, as defined by the development of strictures or fistulae[10], and a higher relapse rate[13]. In addition, the risk of surgery as well as the risk for further resections during disease course were also noted to be higher in smokers in some studies[914] and a recent meta-analysis[15]. The need for steroids and immunosuppressants was found to be higher in smokers compared to non-smokers[16]. Noteworthy, in one study by Cosnes et al[17], immunosuppressive therapy was found to neutralize the effect of smoking on the need for surgery. In a recent paper by Aldhous et al[18], using the Montreal classification, the harmful effect of smoking was only partially confirmed. Although current smoking was associated with a lower rate of colonic disease, the smoking habits at diagnosis were not associated with time to development of stricturing disease, internal penetrating disease, perianal penetrating disease, or time until first surgery.

Finally, early postoperative use of azathioprine (AZA, at a dose of 2-2.5 mg/kg per day) appeared to delay postoperative recurrence in comparison to a historical series or placebo groups in randomized, controlled trials[19]. Furthermore, in a recent withdrawal study by the GETAID group[20], the authors provide evidence for the benefit of long-term AZA therapy beyond 5 years in patients with prolonged clinical remission. In contrast, initial requirement for steroid use [OR: 3.1 (95% CI: 2.2-4.4)], an age below 40 years (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.3-3.6), and the presence of perianal disease (OR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2-2.8) were associated with the development of disabling disease in the study by Beaugerie et al[21] The positive predictive value of disabling disease in patients with two and three predictive factors for disabling disease was 0.91 and 0.93, respectively.

In this study, the authors aimed to assess the combined effect of disease phenotype, smoking, and medical therapy (steroid, AZA, AZA/biological) on the probability of disease behavior change in a cohort of Hungarian CD patients.

Three hundred and forty well-characterized, unrelated, consecutive CD patients (age: 38.1 ± 13.2 years, M/F: 155/185, duration: 9.4 ± 7.5 years) with a complete clinical follow-up were included. A detailed clinical phenotypic description of these patients is presented in Table 1.

| CD (n = 340) | |

| Male/female | 155/185 |

| Age (yr) | 38.1 ± 13.2 |

| Age at presentation (yr) | 28.7 ± 12.4 |

| Duration (yr) | 9.4 ± 7.5 |

| Familial IBD | 39 (11.4) |

| Location | |

| L1 | 75 |

| L2 | 99 |

| L3 | 161 |

| All L4 | 22 |

| L4 only | 5 |

| Behavior at diagnosis | |

| B1 | 198 |

| B2 | 65 |

| B3 | 77 |

| Behavior change from B1 to B2/B3 | 61 (30.8) |

| Perianal disease | 117 (34.4) |

| Frequent relapse | 126 (37.1) |

| Arthritis | 127 (37.5) |

| PSC | 10 (2.9) |

| Ocular | 17 (5.0) |

| Cutaneous | 43 (12.6) |

| Steroid use | 264 (77.6) |

| Azathioprine use | 216 (63.5) |

| Azathioprine intolerance | 36 (14.3) |

| Biological use | 71 (20.9) |

| Surgery/reoperation | 158 (46.5)/52 (32.8) |

| Smoking habits | |

| No | 151 |

| Ex | 36 |

| Yes | 153 |

The diagnosis was based on the Lennard-Jones Criteria[22]; age, age at onset, presence of familial IBD, presence of extraintestinal manifestations; arthritis: peripheral and axial; ocular manifestations: conjunctivitis, uveitis, iridocyclitis; skin lesions: erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum; and hepatic manifestations: primary sclerosing cholangitis, frequency of flare-ups (frequent flare-up: > 1 per year). The disease phenotype (age at onset, duration, location, and behavior) was determined according to the Montreal Classification[4] (non-inflammatory behavior: either stricturing or penetrating disease). Perianal disease and behavior change during follow-up were also registered. Medical therapy was registered in detail [e.g. steroid and/or immunosuppressive/biological therapy use, AZA intolerance as defined by the ECCO (European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation) Consensus Report[23]], need for surgery/reoperation (resections) in CD, and time-point of surgery/reoperation and smoking habits, were investigated by reviewing the medical charts and completing a questionnaire. Only patients with a confirmed diagnosis for more than 1 year were enrolled.

Definitions of AZA/biological therapy use and smoking: patients were regarded as AZA users if they took a dose of ≥ 1.5 mg/kg body weight for at least 6 mo. Early use was considered if the use of immunomodulatory therapy preceded the behavior change by at least 6 mo. According to the Center’s policy, if AZA was started, its use was not halted even in patients with long-term clinical remission. The rate of AZA intolerance was 14.3% (including 36 additional patients), and these patients were classified as AZA-non-users. Common intolerance reactions were leukopenia, abdominal pain, and in three patients, pancreatitis. Biological therapy use was considered if the patient received at least a full, anti-tumor necrosis factor induction therapy at an appropriate dose. The definition of smoking consisted of smoking ≥ 7 cigarettes/wk for at least 6 mo[15–18] at the time of diagnosis and/or during follow-up, within 1 year of diagnosis or behavior change. Patients were interviewed on their smoking habits at the time of diagnosis and during the regular follow-up visits. Moreover, due to Hungarian health authority regulations, a follow-up visit is obligatory for IBD patients at a specialized gastroenterology centre every 6 mo. Otherwise, the conditions of the health insurance policy change and they forfeit their ongoing subsidized therapy. Consequently, the relationship between the IBD patients and their specialists is a close one. The referred patients were retrospectively interviewed about their smoking habits at the time of referral and thereafter. Smoking cessation was defined as complete abstinence of at least 1 year’s duration. Only 16 (4.7%) CD patients stopped smoking during the course of the disease, while 2 additional CD patients started smoking after the diagnosis. In patients with change in disease behavior, all CD patients stopped smoking following the change. Since macroscopic lesions on the ileal side of the anastomosis observed 1 year following surgery were not different between smokers and non-smokers and there was no significant difference reported between ex-smokers and non-smokers in reoperation rates in a recent meta-analysis [1524], ex-smokers at the time of diagnosis were included in the non-smoker group.

Detailed clinical phenotypes were determined by thoroughly reviewing the patients’ medical charts, which had been collected in a uniform format. The central coordination of sample and database management was completed at the 1st Department of Medicine, Semmelweis University (by PLL, TS). Data capture was prospective except for referred patients in whom disease course until referral was registered at the date of the referral and prospectively thereafter. Data analysis was done retrospectively. The study was approved by the Semmelweis University Regional and Institutional Committee of Science and Research Ethics.

Variables were tested for normality using Shapiro Wilk’s W test. The t-test with separate variance estimates, ANOVA with post hoc Scheffe test, χ2-test, and χ2-test with Yates correction were used to evaluate differences within subgroups of IBD patients. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted for analysis with the LogRank and Breslow tests. Additionally, forward stepwise Cox regression analysis was used to assess the association between categorical clinical variables and surgical requirements. P < 0.05 was considered as significant. For the statistical analysis, SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used with the assistance of a statistician (Dr. Peter Vargha).

In a univariate analysis, behavior change from B1 to B2/B3 during follow-up was associated with disease duration, location, presence of perianal disease, smoking at diagnosis, frequency of relapses, steroid use, early AZA use, AZA/biological therapy use and need for resective surgery (Table 2). Although ocular manifestations were also associated with behavior change (3.6% vs 11.5%, P = 0.033), this became non-significant after Bonferroni correction. Patients with a change in disease behavior had significantly longer disease duration (12.3 ± 7.6 years vs 7.4 ± 6.5 years, P < 0.001).

| Factor | Prevalence without behavior change | Prevalence with behavior change | P-value | OR | 95% CI |

| Disease location | |||||

| L1 | 19 (13.9) | 17 (27.9) | |||

| L2 | 55 (40.1) | 18 (29.5) | 0.04 | - | - |

| L3 | 63 (46) | 25 (41) | |||

| L4 | 0 | 1 (1.6) | |||

| Perianal disease | 30 (22.2) | 30 (49.2) | < 0.001 | 3.4 | 1.78-6.46 |

| Frequent relapses | 18 (13.1) | 19 (31.1) | 0.003 | 3.0 | 1.43-6.23 |

| Disease duration (> 10 yr) | 28 (20.4) | 35 (57.4) | < 0.001 | 5.3 | 2.7-10.1 |

| Smoking | 51 (37.2) | 32 (52.5) | 0.04 | 1.9 | 1.02-3.45 |

| Steroid use | 106 (77.4) | 59 (96.7) | 0.001 | 8.6 | 2.00-37.3 |

| Early azathioprine use | 79 (57.7) | 24 (39.3) | 0.017 | 0.48 | 0.26-0.88 |

| Early azathioprine/biological use | 83 (60.6) | 25 (41) | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.24-0.84 |

| Need for operation | 19 (13.9) | 37 (60.7) | < 0.001 | 9.6 | 4.72-19.4 |

In a logistic regression model, disease duration, presence of perianal disease, smoking, steroid use, and early AZA use prior to behavior change were independent predictors for change in disease behavior (Table 3). If early AZA use was changed to early AZA and/or biological therapy use (Coefficient: -1.221, P = 0.002, OR: 0.29, 95% CI: 1.34-0.64) in the same logistic regression model, the associations remained unchanged.

| Factor | Coefficient | P-value | OR | 95% CI |

| Disease location | -0.385 | 0.13 | - | - |

| Longer disease duration (≤ 10 yr vs > 10 yr) | 1.476 | < 0.001 | 4.37 | 2.04-9.38 |

| Perianal disease | 1.351 | 0.001 | 3.86 | 1.72-8.67 |

| Frequent relapses | 0.388 | 0.404 | - | - |

| Smoking | 1.015 | 0.009 | 2.76 | 1.29-5.89 |

| Steroid use | 2.089 | 0.01 | 8.07 | 1.64-39.7 |

| Early azathioprine use | -1.055 | 0.006 | 0.35 | 0.16-074 |

Disease location, perianal disease, early AZA or AZA/biological therapy, steroid use (LogRank P = 0.004 and Breslow P = 0.005) and smoking were significant determinants for time to behavior change surgery in a Kaplan-Meier analysis using LogRank and Breslow tests (Figure 1).

To further evaluate the effect of the above variables on the probability of behavior change, we performed a forward stepwise proportional Cox regression analysis. Each of the above variables was independently associated with the probability of disease behavior change (Table 4). The result was the same if early AZA/biological therapy use (P = 0.002, HR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.25-0.73) was incorporated in the same analysis.

| P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

| Disease location | 0.001 | ||

| L1 | 0.023 | 2.13 | 1.11-4.08 |

| L2 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.27-1.001 |

| L3 | Reference | ||

| Perianal disease | |||

| Yes | < 0.001 | 3.26 | 1.90-5.59 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Steroid use | |||

| Yes | 0.006 | 7.48 | 1.79-31.2 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Early azathioprine use | |||

| Yes | 0.005 | 0.46 | 0.27-0.79 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Smoking status | |||

| Yes | 0.032 | 1.79 | 1.05-3.05 |

| No | Reference |

In the present study, we assessed, for the first time, the combined effect of disease phenotype and medical therapy on the probability of disease behavior change in a well-characterized CD cohort with a strict clinical follow-up. This study has shown that perianal disease, disease location, prior steroid, early AZA or AZA/biological therapy were significant independent predictors of disease behavior change during follow-up in patients with CD, in a stepwise proportional Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier analysis.

In accordance with the findings by Tarrant et al[3], the presence of perianal disease was associated with a 3-4-fold increased risk of developing complicated disease behavior in patients with non-stricturing, non-penetrating disease at the time of diagnosis. Interestingly, in both studies, approximately 50%-55% of patients with perianal disease and only 15%-20% of patients without perianal disease developed a complicated disease behavior after 10 years of follow-up. In the present study, however, only 60% of the patients presented with B1 behavior, representing the more severe disease population in referral centers. In contrast, the Australian study reports the results of a population-based cohort follow-up. Therefore, our results are not only confirmatory, but enable us to extrapolate on the finding that perianal disease is a poor prognostic factor in referral center IBD populations.

In addition, similar to the Australian study, the present study found that progression to complicated disease was more rapid in those with small bowel than colonic disease location. The HR was significantly lower (0.54, P = 0.05) for colonic disease and significantly higher for ileal disease (2.13, P = 0.023) compared to an ileocolonic location in the Cox regression analysis. The same conclusions were reached when data were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method using the LogRank and Breslow tests for comparison. Of note, while the L1 and L3 curves ran parallel after 150 mo, the relatively small number of patients in the L1 group may have introduced a bias in the analysis. These results were only partially confirmed by Aldhous et al[18]. In 275 CD patients, colonic disease was negatively associated with the time required for development of stricturing complications (P < 0.001), while any upper gastrointestinal disease (and tendentially ileocolonic disease, P = 0.066) was the only factor significantly increasing the risk of development of fistulizing complications. Finally, small bowel involvement, stricturing disease, and a young age at diagnosis were associated with disease recurrence in another Dutch population-based study[7].

In the present study, we could not confirm frequency of relapses as an independent prognostic factor for disease behavior change. This is somewhat in contrast with the findings by Munkholm et al[25], where the relapse rate within a year of diagnosis and in the following 2 years, was positively correlated (P = 0.00001) with the relapse rate in the following 5 years in patients with CD.

The findings were slightly different if the authors assessed the clinical factors associated with the development of irreversible structural damage. After a multivariate analysis, only stricturing behaviour at diagnosis (HR: 2.11, P = 0.0004) and weight loss (> 5 kg) at diagnosis (HR: 1.67, P = 0.0089) were independently associated with time to the development of severe disease in the study by Loly et al[8]. The definition of severe, non-reversible damage was, however, much more rigorous. It was defined by the presence of at least one of the following criteria: the development of complex perianal disease, any colonic resection, two or more small-bowel resections (or a single small-bowel resection measuring more than 50 cm in length) or the construction of a definite stoma. Nonetheless, medical therapy was not included in either of the previous studies.

Similarly, although the effect of smoking was extensively investigated in IBD, most studies failed to investigate the complex associations between smoking, disease phenotype, and medical therapy. A recent review[10] and previous data have demonstrated that current smoking was more frequently associated with complicated disease, penetrating intestinal complications[910], and greater likelihood to progress to complicated disease, as defined by the development of strictures or fistulae[11]. In accordance, in the present study, smoking at the time of diagnosis was independently associated with time to behavior change from a non-stricturing, non-penetrating phenotype to complicated disease behavior in CD in a Cox regression model.

However, this was not a universal finding. In a recent paper by Aldhous et al[18], using the Montreal classification, the harmful effect of smoking was only partially confirmed. Although current smoking was associated with less colonic disease, the smoking habits at diagnosis were not associated with time to development of stricturing disease, internal penetrating disease, perianal penetrating disease, or time to first surgery. In contrast, disease location was associated with the need for surgery.

A more solid end-point was also deleteriously affected by smoking in the present study; the need for intestinal resection but not reoperation was also increased in smokers (HR: 3.19, P < 0.001) not treated with immunosuppressive therapy, especially in females, in accordance with data from Cosnes et al[26]. Much emphasis was also placed, by some authors, on investigating the association between the amount of smoking and the above variables in both CD and ulcerative colitis. In a recent publication, the authors[18] did not find a significant association between pack-years of smoking and disease behavior or need for surgery. In addition, in a recent French publication[27], light smokers had higher resection rates compared to non-smokers in CD, suggesting that complete smoking cessation should be advised for all smokers with CD.

The key to explaining these conflicting results lies partly in the study by Cosnes et al[17], where the authors have demonstrated that immunosuppressive therapy neutralizes the effect of smoking on the need for surgery. Therefore, we aimed to analyze the effect of smoking in a more complex setting. After obtaining the results of the univariate and Kaplan-Meier analyses, we performed both a logistic regression analysis adjusted to disease duration as an independent variable and a stepwise proportional Cox regression analysis to investigate the relative weight of the risk factors. In this analysis, perianal disease, smoking, steroid use, and AZA or AZA/biological therapy use before the behavior change were independently associated with time to disease behavior change. However, a partial recall bias, especially in the referral patients, where smoking habits were analyzed in a partially retrospective manner, cannot be excluded.

Finally, the initial requirement for steroid use (OR: 3.1, 95% CI: 2.2-4.4), an age below 40 years at diagnosis (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.3-3.6), and the presence of perianal disease (OR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2-2.8) were associated with the development of disabling disease in the study by Beaugerie et al[21] The positive predictive values of disabling disease in patients with two and three predictive factors for disabling disease were 0.91 and 0.93, respectively. Nonetheless, the prevalence of disabling disease was approximately 80.5% at 5 years in the entire patient group, which makes these criteria less valuable in clinical practice. Moreover, the authors classified the need for immunosuppressive therapy as one potential disabling factor, which in light of the present study, is rather controversial. In the present study, prior steroid use was an independent predictor of time to change in disease behavior. However, again, because of the high prevalence of overall steroid use, the confidence interval is wide and, consequently, the clinical usefulness of this marker is relatively low.

In adults, early postoperative use of AZA at a dose of 2-2.5 mg/kg per day seemed to delay postoperative recurrence in comparison to a historical series or placebo groups in randomized, controlled trials[19]. Furthermore, in a recent withdrawal study by the GETAID group[20], the authors provided evidence for the benefit behind long-term AZA therapy beyond 5 years in patients with prolonged clinical remission. The most convincing data to support the benefit from early use of AZA, however, comes from the pediatric literature[28], where in a randomized, controlled trial in 55 children, early 6-mercaptopurine use was associated with a significantly lower relapse rate (only 9%) compared with 47% of controls (P = 0.007). Moreover, the duration of steroid use was shorter (P < 0.001) and the cumulative steroid dose lower at 6, 12 and 18 mo (P < 0.01). More recently, also in a pediatric setting, this strategy was found to be associated with a lower hospitalization rate[29]. Similarly, in the present study, early AZA or AZA/biological therapy was an independent preventive factor associated with decreased probability of developing complicated disease behavior during the course of the disease (HR: 0.46 and 0.43).

In conclusion, in the present study, we have shown that the complex analysis of disease phenotype, medication history, and smoking habits is needed, in order to study the factors associated with change in disease behavior in patients with IBD. Our data suggest that perianal disease, current smoking, prior steroid use, early AZA or AZA/biological therapy are predictors of disease behavior change in patients with CD.

Using the Vienna classification system, it has been shown in clinic-based cohorts that there can be a significant change in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) disease behavior over time, whereas disease location remains relatively stable. Early age at diagnosis, disease location, perianal disease and, in some studies, smoking were associated with the presence of complicated disease and surgery in previous studies.

The combined effect of markers of disease phenotype (e.g. age, gender, location, perianal disease) and medical therapy (steroid use, early immunosuppression) on the probability of disease behavior change have not, however, been studied in detail thus far in the published literature.

In the present study, the authors have shown in a well-characterized Crohn’s disease (CD) cohort with strict clinical follow-up, that the complex analysis of disease phenotype, medication history, and smoking habits is needed in order to study the factors associated with change in disease behavior in patients with IBD. Their data suggest that perianal disease, current smoking, prior steroid use, early azathioprine (AZA) or AZA/biological therapy are predictors of disease behavior change in patients with CD.

New data with easily applicable clinical information may assist clinicians in everyday, practical decision-making, when choosing a treatment strategy for their CD patients.

Vienna-Montreal classification: classification systems of CD disease phenotypes. The Vienna classification assesses the age at presentation, disease location and disease behavior. In the Montreal classification, the broad categories for CD classification remain the same; however, changes were made within each category. First, a new category was introduced for those aged 16 years or younger at the time of diagnosis, to separate pediatric from adult-onset IBD. Second, upper gastrointestinal disease and perianal disease became disease modifiers, which may coexist with any disease behavior or location.

The present article provides valuable information regarding clinical prognostic factors of phenotype changes of CD over time. The study was performed in a large cohort of patients.

| 1. | Lakatos PL, Fischer S, Lakatos L, Gal I, Papp J. Current concept on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease-crosstalk between genetic and microbial factors: pathogenic bacteria and altered bacterial sensing or changes in mucosal integrity take "toll" ? World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1829-1841. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Lakatos PL. Recent trends in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: up or down? World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6102-6108. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Tarrant KM, Barclay ML, Frampton CM, Gearry RB. Perianal disease predicts changes in Crohn's disease phenotype-results of a population-based study of inflammatory bowel disease phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3082-3093. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5-36. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Louis E, Collard A, Oger AF, Degroote E, Aboul Nasr El Yafi FA, Belaiche J. Behaviour of Crohn's disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut. 2001;49:777-782. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Sachar DB, Bodian CA, Goldstein ES, Present DH, Bayless TM, Picco M, van Hogezand RA, Annese V, Schneider J, Korelitz BI. Is perianal Crohn's disease associated with intestinal fistulization? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1547-1549. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Romberg-Camps MJ, Dagnelie PC, Kester AD, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Cilissen M, Engels LG, Van Deursen C, Hameeteman WH, Wolters FL, Russel MG. Influence of phenotype at diagnosis and of other potential prognostic factors on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:371-383. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Loly C, Belaiche J, Louis E. Predictors of severe Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:948-954. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Lindberg E, Järnerot G, Huitfeldt B. Smoking in Crohn's disease: effect on localisation and clinical course. Gut. 1992;33:779-782. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Mahid SS, Minor KS, Stevens PL, Galandiuk S. The role of smoking in Crohn's disease as defined by clinical variables. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2897-2903. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Picco MF, Bayless TM. Tobacco consumption and disease duration are associated with fistulizing and stricturing behaviors in the first 8 years of Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:363-368. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Louis E, Michel V, Hugot JP, Reenaers C, Fontaine F, Delforge M, El Yafi F, Colombel JF, Belaiche J. Early development of stricturing or penetrating pattern in Crohn's disease is influenced by disease location, number of flares, and smoking but not by NOD2/CARD15 genotype. Gut. 2003;52:552-557. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Cosnes J, Carbonnel F, Carrat F, Beaugerie L, Cattan S, Gendre J. Effects of current and former cigarette smoking on the clinical course of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1403-1411. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Sutherland LR, Ramcharan S, Bryant H, Fick G. Effect of cigarette smoking on recurrence of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1123-1128. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Reese GE, Nanidis T, Borysiewicz C, Yamamoto T, Orchard T, Tekkis PP. The effect of smoking after surgery for Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1213-1221. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Cosnes J. Tobacco and IBD: relevance in the understanding of disease mechanisms and clinical practice. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:481-496. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Cosnes J, Carbonnel F, Beaugerie L, Le Quintrec Y, Gendre JP. Effects of cigarette smoking on the long-term course of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:424-431. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Aldhous MC, Drummond HE, Anderson N, Smith LA, Arnott ID, Satsangi J. Does cigarette smoking influence the phenotype of Crohn's disease? Analysis using the Montreal classification. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:577-588. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Domènech E, Mañosa M, Bernal I, Garcia-Planella E, Cabré E, Piñol M, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Boix J, Gassull MA. Impact of azathioprine on the prevention of postoperative Crohn's disease recurrence: results of a prospective, observational, long-term follow-up study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:508-513. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Treton X, Bouhnik Y, Mary JY, Colombel JF, Duclos B, Soule JC, Lerebours E, Cosnes J, Lemann M. Azathioprine withdrawal in patients with Crohn's disease maintained on prolonged remission: a high risk of relapse. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:80-85. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:650-656. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:2-6; discussion 16-19. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Beglinger C, Kupcinkas L, Geboes K, Barakauskiene A, Villanacci V, Von Herbay A, Warren BF. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: definitions and diagnosis. Gut. 2006;55 Suppl 1:i1-i15. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Cosnes J, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Gendre JP. Smoking cessation and the course of Crohn's disease: an intervention study. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1093-1099. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Disease activity courses in a regional cohort of Crohn's disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:699-706. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Afchain P, Beaugerie L, Gendre JP. Gender differences in the response of colitis to smoking. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:41-48. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Sokol H, Beaugerie L, Cosnes J. Effects of light smoking consumption on the clinical course of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:734-741. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Markowitz J, Grancher K, Kohn N, Lesser M, Daum F. A multicenter trial of 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone in children with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:895-902. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Punati J, Markowitz J, Lerer T, Hyams J, Kugathasan S, Griffiths A, Otley A, Rosh J, Pfefferkorn M, Mack D. Effect of early immunomodulator use in moderate to severe pediatric Crohn disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:949-954. [Cited in This Article: ] |