Published online Jun 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i21.3311

Revised: May 28, 2004

Accepted: June 17, 2004

Published online: June 7, 2005

AIM: To describe the use of hand-assisted laparoscopic surg-ery (HALS) as an alternative to open conversion for complex gall-stone diseases, including Mirizzi syndrome (MS) and mimic MS.

METHODS: Five patients with MS and mimic MS of 232 consecutive patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecyst-ectomies were analyzed. HALS without a hand-port device was performed as an alternative to open conversion if the anatomy was still unclear after the neck of the gallbladder was reached.

RESULTS: HALS was performed on three patients with MS type I and 2 with mimic MS owing to an unclear or abnormal anatomy, or an unusual circumstance in which an impacted stone was squeezed out from the infundibulum or the aberrant cystic duct impossible with laparoscopic approach. The median operative time was 165 min (range, 115-190 min). The median hand-assisted time was 75 min (range, 65-100 min). The median postoperative stay was 4 d (range, 3-5 d). The postoperative course was uneventful, except for 1 patient complicated with a minor incision infection.

CONCLUSION: HALS for MS type I and mimic MS is safe and feasible. It simplifies laparoscopic procedure, and can be used as an alternative to open conversion for complex gallstone diseases.

- Citation: Wei Q, Shen LG, Zheng HM. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery for complex gallstone disease: A report of five cases. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(21): 3311-3314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i21/3311.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i21.3311

Mirizzi syndrome (MS) is an uncommon complication of chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis. The diagnosis of MS is established after the demonstration of a compression or obstruction of the bile duct by stone located in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct. Laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of MS has been reported at a few centers[1-4]; however, laparoscopic intervention for the MS has its limitations and may result in more complications and a significant conversion rate[5,6]. The aim of this paper is to describe the use of hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) as an alternative to open conversion for the MS and mimic MS. Mimic MS is defined as an impacted stone(s) in the neck of gallbladder with short cystic duct, causing obscured Calot’ triangle without obstructive jaundice.

From June 2003 to December 2003, 232 consecutive patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) by a single surgeon and his team. Five of the patients with MS and mimic MS were analyzed here. Three patients were of MS type I, according to McSherry Classification, and two patients had mimic MS. Data and video-recordings were collected with regard to the patients’ age, sex, presentation, investigations, operative findings, method and time, and causes of HALS.

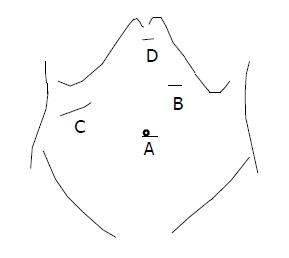

The procedure was carried out using the conventional laparoscopic method of insertion of Trocars. The camera port was placed via an umbilical incision. Once the decision was made to perform HALS, a right subcostal oblique incision was done. The incision approximated the surgeon’s hand size (6.0-6.5 cm). Following the introduction of the surgeon’s left hand, the incision was tightened by a towel clip. The size of the split-muscles should be smaller. The pneumoperitoneum was re-established. A gauze roll was placed around the surgeon’s wrist if gas was escaped. These can provide a seal to avoid gas escape. The introduction site of the hand should not be too close to the operating field, otherwise the hand itself may interfere with the laparoscopic view and instrumentation. The working port was inserted into the left subcostal region to allow enough room for manipulation (Figure 1). The surgeon and the assistant/camera operator stood on the left side of the patient.

We tried an initial fundus-first dissection (FFD) when the presence of MS was suspected or when Calot’s triangle was completely obscured. HALS was performed as an alternative to open conversion if the anatomy is still unclear after the neck of the gallbladder is reached. The operative principles are similar to those recommended for open procedures. A partial or subtotal cholecystectomy was performed with suturing closure or with endoloops closure; the intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) was performed by a direct injection into the bile duct or via the cystic duct. The IOC clarified the anatomy and excluded bile duct stones. A suction drain was placed in the subhepatic space at the end of the procedure in all patients.

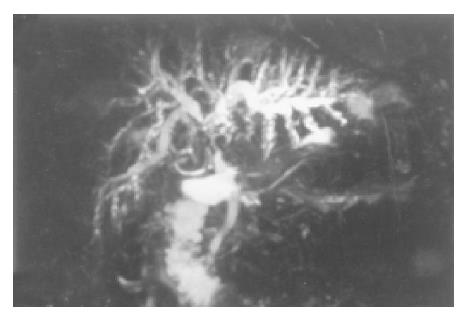

Table 1 presents the demographic data of the five patients. There were four men and one woman. The average age was 52 years (range, 33-68 years). All patients presented with histories of recurrent right upper quadrant pain, three MS patients were jaundiced with abnormal liver function at presentation, and one patient had pancreatitis with jaundice history. Of two mimic MS patients presented with subacute cholecystitis. Preoperative investigations of the five patients were as follows: In three MS patients, ultrasonography showed an atrophic gallbladder with stones, and intrahepatic bile duct or common hepatic duct (CHD) dilatation. Magnetic resonance cholang-iopancreaticography (MRCP) (Figure 2) and computed tomography (CT) scan were used, and MS was established provisionally. Ultrasonography showed gallbladder distension with specific mention of the neck stones in two mimic MS patients.

| Patient No. | Age | Sex (yr) | Bilirubin (mg/dL) | ALP (IU/L) | AST (IU/L) |

| 1 | 33 | M | 8.5 | 337 | 68 |

| 2 | 63 | M | 1.0 | 71 | 59 |

| 3 | 43 | M | 0.9 | 83 | 30 |

| 4 | 51 | M | 6.2 | 211 | 70 |

| 5 | 68 | F | 5.0 | 277 | 350 |

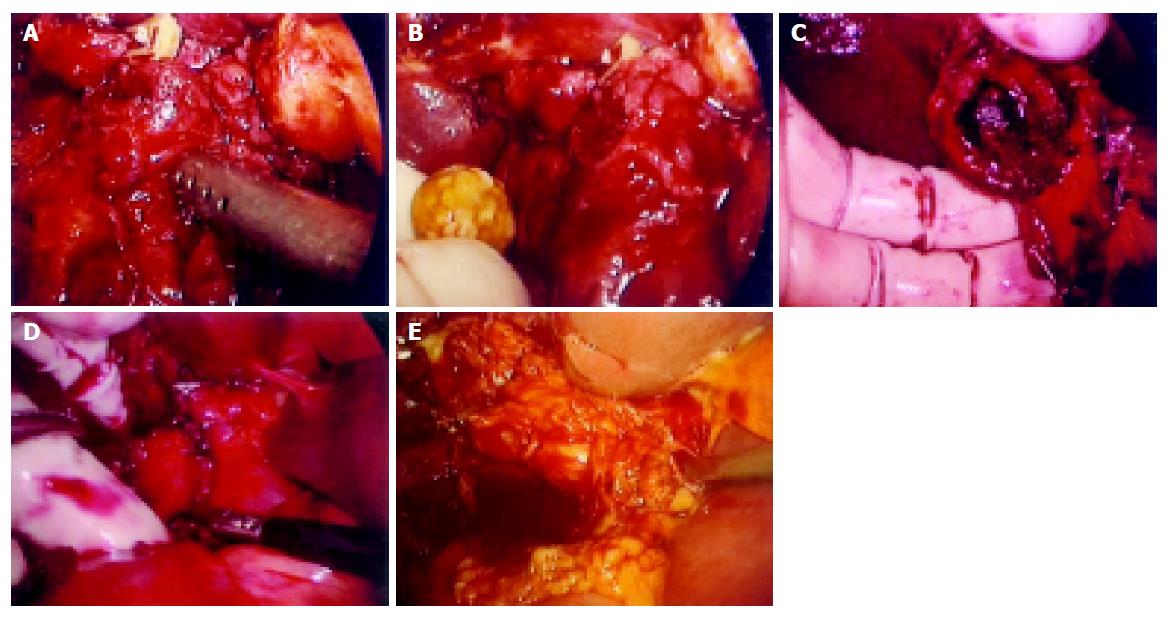

Table 2 presents the causes of HALS and operative method for the five patients. Case 1 underwent subtotal cholec-ystectomy for an atrophic gallbladder with multiple stones, but one 1.0-cm stone impacted in the infundibulum, which was fused with the CHD, impossible to remove with laparoscopic instruments (Figure 3A and 3B). The operative findings of case 4 proved a contracted atrophic gallbladder, one 2.5-cm large stone with extrinsic compression of the CHD, and obliteration of Calot’s triangle (Figure 3C and 3D). Case 5 had dense adhesions of Calot’s triangle, and one 0.8-cm stone impacted in the cystic duct incapable of milked back. IOC was performed in case 4 and case 5 with the aid of the hand. Case 2 had one 2.5-cm neck stone, and case 3 had two neck stones of 0.5- and 0.8-cm; both had severely inflamed large gallbladders. Causes of HALS were unclear anatomy in the Calot’s triangle shown in Figure 3E, and the bleeding of FFD and gallbladder empyema, respectively (Table 2). Both short cystic ducts were ligated with a 12-mm Lapro-Clip. The histopathological results showed both acute suppurative cholecystitis. The intra-abdominal hand-aid operation was easier and quicker for retraction of the liver and gallbladder, finger dissection, identification of bile duct, and manual hemostasis.

| Patient No. | Causes of HALS | Operative method |

| 1 | Impacted stone in infundibulum | Subtotal Cholecystectomy |

| 2 | Obscured Calot triangle, bleeding of FFD | Total cholecystectomy |

| 3 | Obscured Calot triangle, GB emphysema | Partial cholecystectomy |

| 4 | Contracted atrophic GB, obliterated Calot triangle | Partial cholecystectomy |

| 5 | Dense adhesions of Calot triangle, impacted stone in cystic duct | Subtotal Cholecystectomy |

The median operative time was 165 min (range, 115-190 min). The median hand-assisted time was 75 min (range, 65-100 min). The median postoperative stay was 4 d (range, 3-5 d) (Table 3). The estimated median operative blood loss was 80 mL (range, 50-100 mL). Only two patients needed an additional single dose of 75 mg pathidine. The patients were encouraged to have oral intake at the 1st day after surgery, and early ambulation as well. The postoperative course was uneventful, except for one patient who had a minor incision infection. Seven to twenty-one days after surgery, liver function was back to normal range in three MS patients. All patients remain asymptomatic within a follow-up period of 15-36 wk (median, 25 wk).

| Patient No. | Operative time (min) | Hand-assisted time (min) | Postoperative stays (d) | Clinical diagnosis |

| 1 | 165 | 75 | 4 | MS type I |

| 2 | 165 | 70 | 3 | Mimic MS |

| 3 | 115 | 65 | 4 | Mimic MS |

| 4 | 180 | 100 | 5 | MS type I |

| 5 | 190 | 90 | 4 | MS type I |

MS has a reported incidence of 0.7-1.4% of all patients undergoing biliary surgery[2] and is 1.3% (3/232) in our cases. However, our three patients were of MS type I. This difference is possibly a consequence of early operation in the era of LC. Csendes suggested that the MS type I and cholecystobiliary fistulas have different stages of the same disease process[7]. The presence of a short or absent cystic duct may increase the likelihood of MS occurrence. This indicates that patients with mimic MS or MS type I are more often encountered at LC[8].

Ultrasound is a screening investigation in patients of biliary symptoms. A single large stone in the neck of the gallbladder commonly raises suspicion of MS. In our cases, an atrophic gallbladder with stones was more frequently a feature. If such findings are recognized at ultrasonography, further evaluation of the biliary tree is required. In our studies, MRCP and CT were used in three suspected MS patients and preliminary diagnosis of MS was made. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the investigation currently recommended, however, surgery is needed in most patients[1,2]. The roles of MRCP and ERCP remain to be further evaluated[9].

Successful laparoscopic surgery for MS has been reported in Refs.[1-4], however, it can be extremely challenging and time-consuming, and may be associated with increased intraoperative and postoperative complications, and the cumulative conversion rate being 68% among these cases[5,6].

In MS and mimic MS patients, abnormal anatomy such as the presence of contracted atrophic or distended gallbladder with an impacted stone(s) in the neck, often led to problems in grasping or retracting the gallbladder and liver, and contributed to the difficulty of laparoscopic procedure[10]. In laparoscopic FFD fashion, however, retraction of the liver and control of unexpected bleeding may still be the limiting factors, especially in an acutely intensive inflamed gallbladder[11].

In our cases, the main causes for HALS were unclear or abnormal anatomy, and a severe adhesion if the neck of the gallbladder has been reached, even after partial or subtotal cholecystectomy was performed (Table 2). Since continued dissection laparoscopically at the obscure Calot’s triangle carries the potential risk of ductal injury and difficulty of unexpected bleeding control, in those situations, HALS can be considered a technical aid in cases in which conversion is required due to unclear anatomy[12-14]. With improved tactile sense and manipulative ability of traction and counter-traction with the hand rather than the instruments, blunt and sharp dissections are achieved expeditiously without fear of injury to the organs. Similarly, finger dissection and finger depression of bleeding are easy and quick. Critical structures such as bile duct and blood vessels are easily identified by tactile feedback, thus having a lower chance of being inadvertently injured[6,13-15].

Another important reason for HALS was unusual maneuvers such as removing an impacted stone in the infundibulum or the aberrant cystic duct, which might be impossible with laparoscopic approach, but readily performed by the intra-abdominal hand in our case 1 and case 5 (Table 2). As far as the identification of gallbladder or bile duct carcinoma is concerned, the ability to palpate and define tissue characteristics manually is helpful[12].

The benefit of HALS is demonstrated by the reduction in operative time owing to improved identification of anatomy, dissection, retraction, and better control of hemorrhagic accidents[6,13-15]. In our initial experience, the median operative time was 165 min and the median hand-assisted time was 75 min. Decision made promptly in HALS could reduce the operative time.

Concerning gas leakage by the procedures without hand-port device, the movement of the hand was limited to some extent, however, it was not difficult to keep the seal of the small incision tight and to avoid loss of gas. The seal with the help of “a towel clip” to maintain pneumoperitoneum was feasible. Gas leakage was encountered in two of five patients, however, the pneumoperitoneum generally was maintained at 10-12 mmHg during surgery. A hand-port device requires much space around a relatively small incision; and in the subcostal oblique incision where the device is placed close to the rib margin and lateral abdominal wall, there can be gas leakage[14]. Moreover, the hand-port device is relatively expensive, leading to an increased cost.

Hand fatigue is one drawback of HALS in long or complicated procedures. Hand fatigue occurred in 2 of 5 procedures due to longer hand-assisted operative time (Table 3). In such cases, the surgeon can remove or have his or hers hand rest for a few minutes. Following the principles of instrument triangulation, with the hand considered as an instrument, this could reduce intraoperative hand fatigue[13,14].

Between June 2001 and June 2003, eight cases of MS were identified in 5310 LC (0.15 %) at our surgical department; six patients had MS type I and two had MS type II. There were three men and five women. The average age was 50 years (range, 38-72 years). All patients were converted to an open procedure with a 15-20 cm subcostal incision. Two cases with injuries of the bile duct (a complete transection and an excision of a duct segment) underwent an end-to-end anastomosis of the injured bile duct over a T-tube and a Roux-en-Y hepatico-jejunostomy with a transanastomotic stent, respectively. The median operative time was 165 min (range, 140-250 min). The median postoperative stay was 5.5 d (range, 4-13 d). The median estimated operative blood loss was 100 mL (range, 80-400 mL). At the end of surgery, a mixture of tramadol plus fentanyl was used maintaining 48-96 h in the analgesia pump for all patients. The patients began to have oral intake from the 2nd to 5th d (median, 3 d) after surgery.

As described above, HALS can improve the success rate and decrease the complication rate of laparoscopic procedures, especially bile duct injuries. It is a mini-access surgery characterized with less pain, earlier oral intake, and decreased hospital stay in comparison with the open operations[12-15].

Experienced surgeons can be successful in performing laparoscopic surgery for MS. However, it is challenging and time-consuming. Our results suggest that HALS without a hand-port device for MS type I and mimic MS is safe and feasible. HALS appears to facilitate difficult laparoscopic procedures, by decreasing operative time and had minimal increase of complications. It can be used as an alternative to open conversion for complex gallstone diseases.

We thank Dr. Robert Jr. Finley for his editorial assistance.

| 1. | Targarona EM, Andrade E, Balagué C, Ardid J, Trías M. Mirizzi's syndrome. Diagnostic and therapeutic controversies in the laparoscopic era. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:842-845. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kok KY, Goh PY, Ngoi SS. Management of Mirizzi's syndrome in the laparoscopic era. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1242-1244. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bagia JS, North L, Hunt DR. Mirizzi syndrome: an extra hazard for laparoscopic surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:394-397. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yeh CN, Jan YY, Chen MF. Laparoscopic treatment for Mirizzi syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1573-1578. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Contini S, Dalla Valle R, Zinicola R, Botta GC. Undiagnosed Mirizzi's syndrome: a word of caution for laparoscopic surgeons--a report of three cases and review of the literature. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999;9:197-203. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Memon MA, Fitzgibbons RJ. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS): a useful technique for complex laparoscopic abdominal procedures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1998;8:143-150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Nava O. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1139-1143. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 230] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dorrance HR, Lingam MK, Hair A, Oien K, O'Dwyer PJ. Acquired abnormalities of the biliary tract from chronic gallstone disease. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:269-273. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Choi BW, Kim MJ, Chung JJ, Chung JB, Yoo HS, Lee JT. Radiologic findings of Mirizzi syndrome with emphasis on MRI. Yonsei Med J. 2000;41:144-146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Strasberg SM, Eagon CJ, Drebin JA. The "hidden cystic duct" syndrome and the infundibular technique of laparoscopic cholecystectomy--the danger of the false infundibulum. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:661-667. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mahmud S, Masaud M, Canna K, Nassar AH. Fundus-first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:581-584. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wolf JS, Moon TD, Nakada SY. Hand assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy: comparison to standard laparoscopic nephrectomy. J Urol. 1998;160:22-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 152] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Targarona EM, Gracia E, Rodriguez M, Cerdán G, Balagué C, Garriga J, Trias M. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Arch Surg. 2003;138:133-141; discussion 141. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Litwin DE, Darzi A, Jakimowicz J, Kelly JJ, Arvidsson D, Hansen P, Callery MP, Denis R, Fowler DL, Medich DS. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) with the HandPort system: initial experience with 68 patients. Ann Surg. 2000;231:715-723. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 148] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Seifman BD, Wolf JS. Technical advances in laparoscopy: hand assistance, retractors, and the pneumodissector. J Endourol. 2000;14:921-928. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |