Published online Oct 28, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i40.4539

Revised: March 23, 2011

Accepted: March 30, 2011

Published online: October 28, 2011

Retroperitoneal duodenal perforation as a result of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy is a rare complication, but it is associated with a relatively high mortality risk, if left untreated. Recently, several endoscopic techniques have been described to close a variety of perforations. In this case report, we describe the closure of a persistent sphincterotomy-related duodenal perforation by using a covered self-expandable metallic biliary (CEMB) stent. A 61-year-old Greek woman underwent an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and sphincterotomy for suspected choledocholithiasis, and a retroperitoneal duodenal perforation (sphincterotomy-related) occurred. Despite initial conservative management, the patient underwent a laparotomy and drainage of the retroperitoneal space. After that, a high volume duodenal fistula developed. Six weeks after the initial ERCP, the patient underwent a repeat endoscopy and placement of a CEMB stent with an indwelling nasobiliary drain. The fistula healed completely and the stent was removed two weeks later. We suggest the transient use of CEMB stents for the closure of sphincterotomy-related duodenal perforations. They can be placed either during the initial ERCP or even later if there is radiographic or clinical evidence that the leakage persists.

- Citation: Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Nastos C, Yiallourou A, Polydorou A, Voros D. Closure of a persistent sphincterotomy-related duodenal perforation by placement of a covered self-expandable metallic biliary stent. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(40): 4539-4541

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i40/4539.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i40.4539

Retroperitoneal duodenal perforation as a result of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy (ES) is a well-recognized complication. Although it is reported to have an incidence of 0.3% to 1.3%, it is associated with a relatively high mortality rate of 7% to 14%[1-4]. The overriding question is whether or not immediate surgical exploration is required or if a trial of non-operative management is safe. Recently, several endoscopic techniques have been described to close a variety of perforations[5,6]. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first report of a delayed closure of a sphincterotomy-related duodenal perforation by placement of a covered self-expandable metallic biliary (CEMB) stent.

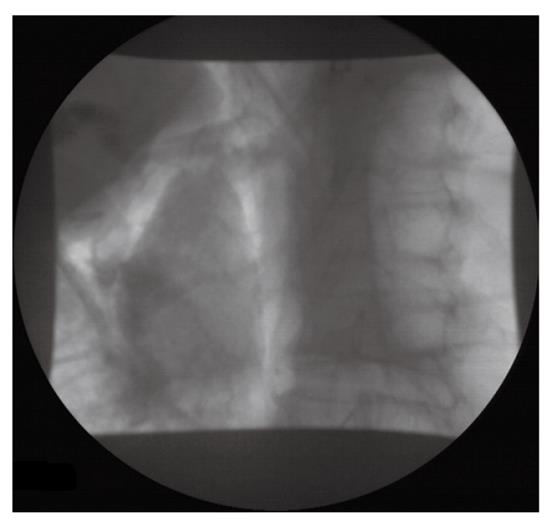

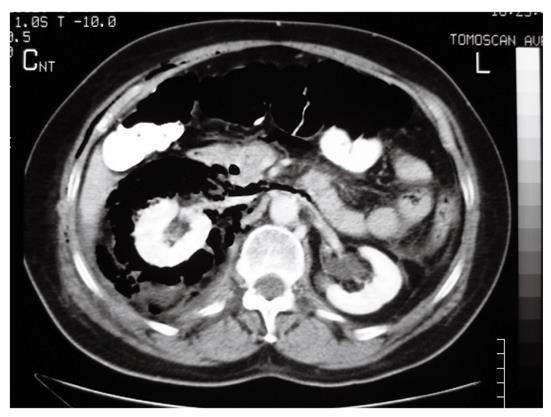

A 61-year-old lady with a history of previous laparoscopic cholecystectomy underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for biliary colic, abnormal liver function tests and a grossly dilated common bile duct (20 mm). The suspected diagnosis was either choledocholithiasis or sphincter of Oddi dysfunction type I. ES was performed over a guidewire using an ERBE VIO 200 S diathermy (ERBE Elektromedizin, Germany) at Endocut mode. Due to an unusual direction of the papilla, the ES was carried out laterally towards the 9 o’clock position. After insertion and removal of the balloon catheter, a visible laceration was recognized just posteriorly to the ES. The presence of free air in the retroperitoneum was immediately apparent (Figure 1). The patient was treated initially with broad spectrum antibiotics and nasogastric drainage. The following day an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed (Figure 2). A large amount of retroperitoneal air was identified, but no leak of contrast was found. Over the following days the patient deteriorated, became pyrexial and unstable, and a laparotomy was carried out on the 15th post-ERCP day. The retroperitoneal space was explored with debridement of necrotic tissue and placement of drains.

The patient’s condition was improved postoperatively, but a high volume duodenal fistula (500-1500 mL/24 h) developed, which was refractory to conservative treatment.

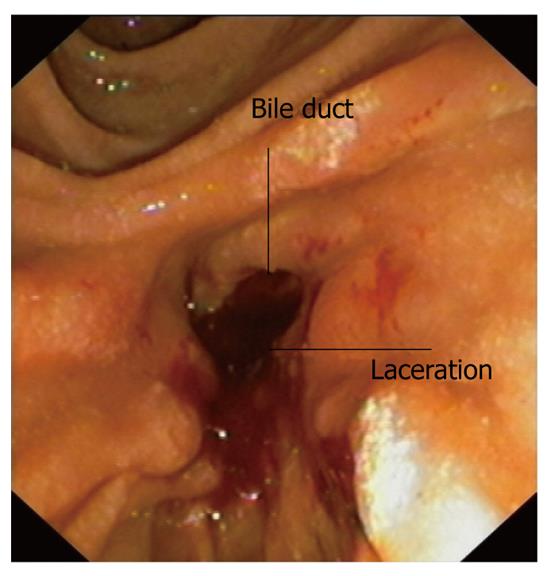

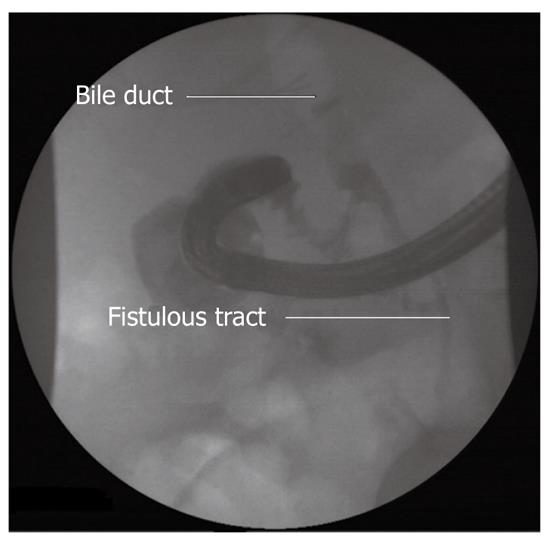

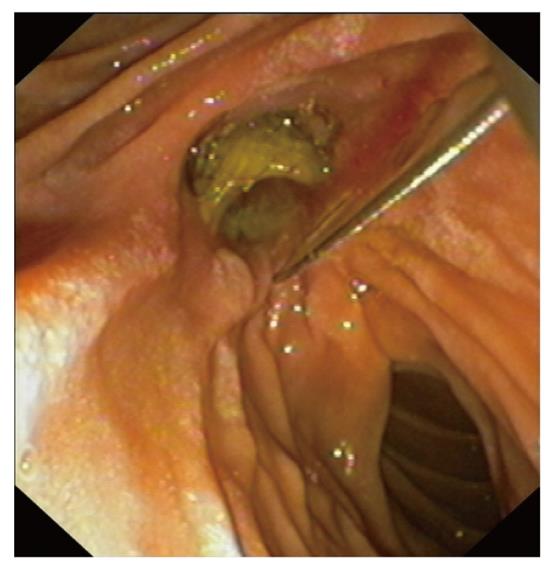

Four weeks later an endoscopy was performed. The procedure was technically difficult because of an edematous duodenum, but the laceration was found at the sphincterotomy site (Figures 3 and 4). A CEMB stent (Wallstent, Boston Scientific) and subsequently a nasobiliary drainage catheter were placed (Figures 5 and 6). The proximal 5 mm uncovered portion of the Wallstent had been cut prior to insertion. The fistula had healed completely a week later and the stent was removed at 2 wk. The nasobiliary drain was left in place for five days, although the output was minimal. A cholangiography and contrast study before removal of the nasobiliary drain showed no existence of leak.

The patient was discharged home 2 mo post-ERCP and remains well 8 mo later.

Perforation during ES is usually retroperitoneal in location. It results from an extension of the incision beyond the intramural portion of the bile duct. It is widely believed that perforation is more likely to occur if the incision strays beyond the usual recommended sector (11 to 1 o’clock)[7]. Due to the low incidence of perforation, the risk factors are not well defined. The risk appears to be increased in patients with Billroth II anastomosis and when needle-knife sphincterotomy is performed[3]. The incision in these situations is not well controlled and therefore the chances of perforation are higher.

No consensus exists on management guidelines, because ES-related retroperitoneal perforations are rare and the clinical consequences vary enormously. In general, non-operative management of these perforations is possible despite the presence of extensive retroperitoneal air, provided the patient remains well clinically. If the patient develops abdominal pain, fever and appears toxic clinically, surgical exploration should be considered[8]. Delayed diagnosis can lead to severe morbidity[9]. Patients with biliary stenting appear to have a lower rate of operative intervention. This is likely related to the higher rate of guidewire-induced injuries in these patients, who are much less likely to require operative intervention[8]. It is possible that biliary stenting has a protective effect by diverting bile into the duodenum instead of into the retroperitoneum. Endoscopic closure of ERCP-related duodenal perforations by using endoclipping devices[10], approximation sutures[5] or duodenal stents[6] have also been described.

The above described endoscopic techniques are applied after the recognition of the perforation during the initial ERCP. In our case, a repeat ERCP was performed 6 wk after the initial procedure, in order to repair the perforation and drain the bile duct. A repeat endoscopy after a duodenal perforation is technically demanding, carries the risk of extending the laceration, and excessive skill is required.

CEMB stents have the advantage of covering the laceration and permit free flow of bile into the duodenum instead of into the retroperitoneal space. Additionally, they protect against the leakage of pancreatic and gastric fluid. The additional use of a nasobiliary drainage catheter may reduce bile flow to the duodenum and allows checking of the healing process by performing contrast studies. Fully covered metallic self-expandable biliary stents should be preferred because they can easily be removed after a short period. In our case, a fully covered stent was not available and we modified a partially covered as mentioned previously.

In conclusion, we suggest the transient use of CEMB stents for the closure of sphincterotomy-related duodenal perforations. They can be placed either during the initial ERCP or even later, if there is radiographic or clinical evidence that the leakage persists.

Peer reviewer: Ji Kon Ryu, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 28 Yeongeon-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul 110-744, South Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-731. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, De Bernardin M, Ederle A, Fina P, Fratton A. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1-10. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Fatima J, Baron TH, Topazian MD, Houghton SG, Iqbal CW, Ott BJ, Farley DR, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Pancreaticobiliary and duodenal perforations after periampullary endoscopic procedures: diagnosis and management. Arch Surg. 2007;142:448-54; discussion 454-5. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Lee TH, Bang BW, Jeong JI, Kim HG, Jeong S, Park SM, Lee DH, Park SH, Kim SJ. Primary endoscopic approximation suture under cap-assisted endoscopy of an ERCP-induced duodenal perforation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2305-2310. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Small AJ, Petersen BT, Baron TH. Closure of a duodenal stent-induced perforation by endoscopic stent removal and covered self-expandable metal stent placement (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1063-1065. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Knudson K, Raeburn CD, McIntyre RC, Shah RJ, Chen YK, Brown WR, Stiegmann G. Management of duodenal and pancreaticobiliary perforations associated with periampullary endoscopic procedures. Am J Surg. 2008;196:975-81; discussion 981-2. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Avgerinos DV, Llaguna OH, Lo AY, Voli J, Leitman IM. Management of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: related duodenal perforations. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:833-838. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Herman L. Hemoclip repair of a sphincterotomy-induced duodenal perforation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:566-568. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |