Published online Dec 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8420

Revised: October 1, 2013

Accepted: October 17, 2013

Published online: December 7, 2013

AIM: To assess systematically the safety and efficacy of bile leakage test in liver resection.

METHODS: Randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials involving the bile leakage test were included in a systematic literature search. Two authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion and extracted the data. A meta-analysis was conducted to estimate postoperative bile leakage, intraoperative positive bile leakage, and complications. We used either the fixed-effects or random-effects model.

RESULTS: Eight studies involving a total of 1253 patients were included and they all involved the bile leakage test in liver resection. The bile leakage test group was associated with a significant reduction in bile leakage compared with the non-bile leakage test group (RR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.23-0.67; I2 = 3%). The white test had superiority for detection of intraoperative bile leakage compared with the saline solution test (RR = 2.38, 95%CI: 1.24-4.56, P = 0.009). No significant intergroup differences were observed in total number of complications, ileus, liver failure, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, pulmonary disorder, abdominal infection, and wound infection.

CONCLUSION: The bile leakage test reduced postoperative bile leakage and did not increase incidence of complications. Fat emulsion is the best choice of solution for the test.

Core tip: Bile leakage is a common complication after hepatic resection and seriously affects postoperative quality of life. The bile leakage test was introduced to prevent bile leakage after liver resection. Many studies have evaluated the feasibility, safety and efficacy of the bile leakage test, however, the clinical significance of this technique remains inconsistent. We conducted a systematic review and showed that the bile leakage test reduced the incidence of postoperative bile leakage and did not increase the incidence of complications. In addition, fat emulsion may be the best choice of solution for the bile leakage test.

- Citation: Wang HQ, Yang J, Yang JY, Yan LN. Bile leakage test in liver resection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(45): 8420-8426

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i45/8420.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8420

With the refinement of surgical techniques and perioperative care in liver surgery, the postoperative morbidity and mortality have markedly decreased. However, the incidence of bile leakage has not changed over the past few decades, ranging from 4.0% to 9.8% in recent studies[1-7]. Biliary complications remain a common cause of major morbidity after hepatic resection[1]. The presence of bile in the peritoneal cavity may impair the normal host defense mechanisms and predispose to the development of sepsis, liver failure and mortality[2,3]. Therefore, many methods have been introduced to prevent bile leakage after liver transection, including intraoperative cholangiography[8], spreading fibrin glue on the transected liver surface[9], assessing bile duct patency by injecting air under ultrasonographic monitoring[10], and the bile leakage test. The latter is a common approach to reduce postoperative bile leakage[11]. With this technique, after cholecystectomy and liver parenchymatous division, a catheter is inserted through the cystic duct into the common bile duct and the distal common bile duct is occluded. A solution, such as isotonic sodium, fat emulsion, indocyanine green or methylene blue, is slowly injected into the biliary tree and a clinical judgment is then made as to whether a bile leak is present on the transected surface of the liver. If so, the bile leakage site will be closed steadily beforehand[11]. Using this technique, some studies[2,11-14] have identified intraoperatively additional potential bile leakage points in 19.7%-80.8% of the patients. The bile leakage test proved to be useful for preventing postoperative bile leakage in several studies, however, other studies suggested no advantage in using the bile leakage test. Moreover, the additional operation associated with the test may also result in a risk of postoperative complications. Some studies have suggested excessive bile duct pressure from the bile leakage test could cause cholangiovenous reflux and cholangitis[15,16].

Many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials have evaluated the feasibility, safety and efficacy of the bile leakage test, however, the clinical significance of this technique remains inconsistent. To date, we have been unable to identify any meta-analysis that assessed the role of the bile leakage test. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the test in liver resection.

We conducted the meta-analysis and systematic review according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions[17] and preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis[18].

A systematic literature search was independently conducted by two authors. We systematically searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, Science Citation Index (Web of Knowledge), PubMed and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database up to June 7, 2013. The search strategies were as follows: (biliary leakage OR bile leakage OR bile fistula OR biliary fistula OR bile leakage test OR biliary complication) AND (hepatic resection OR hepatectomy (MeSH terms) OR liver resection). The literature search was performed with restriction in language to English or Chinese and RCTs or controlled clinical trials. After completing all searches, we merged the search results using Endnote X3 (reference management software) and removed duplicated records. Two independent authors scanned the title and abstract of every record identified by the searches for inclusion. If compliance with inclusion criteria was not clear from the abstract, we retrieved full texts for further assessment.

Types of studies: RCTs and controlled clinical trials were considered for this review.

Types of participants: Patients who were about to undergo selective liver resection for any disease were included in our study, irrespective of age, sex, tumor size and nodule numbers. Trials in which patients required living donor liver transplantation were excluded. Trials in which patients required the bile leakage test without liver resection were excluded.

Types of interventions: We included trials comparing patients with and without the bile leakage test undergoing hepatectomy, or trials comparing bile leakage with different methods.

Types of outcome measures: Primary outcomes: postoperative bile leakage, and intraoperative positive bile leakage; secondary outcomes: operation time, blood loss, postoperative complications, postoperative hospital stay, and duration of drainage.

Selection of studies: Any disagreement during study selection and data extraction was resolved by discussion and referral to a third author for adjudication.

Data extraction: Two authors extracted data on a standard form that included population characteristics, intraoperative parameters, and information about the outcome measures in each trial. In the case of missing data, we contacted the original investigators to request further information.

Quality assessment: Two authors assessed the methodological quality of the trials independently. The Jadad score[19,20] was used to assess the quality of RCTs, with a cumulative score of > 3 indicating high quality. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale[21,22] was used to assess the quality of non-randomized studies, with a score ≥ 5 indicating high quality.

We pooled the synchronized extraction results as estimates of overall treatment effects in a meta-analysis using Review Manager for Windows version 5.0. The estimated effect measures were RR for dichotomous data and weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous data; both reported with 95%CI. We checked all results for clinical and statistical heterogeneity. Clinical heterogeneity was evaluated by assessing study populations and interventions, definition of outcome measures, concomitant treatment, and perioperative management. Heterogeneity was explored by χ2 test with significance setting at P = 0.10, and I2 statistics were used for the evaluation of statistical heterogeneity (I2≥ 50% indicating presence of heterogeneity)[23]. We used a fixed-effects model to synthesize data when heterogeneity was absent, otherwise a random-effects model was used for synthesizing data. Data are presented as forest plots and the funnel plot was used to assess publication bias.

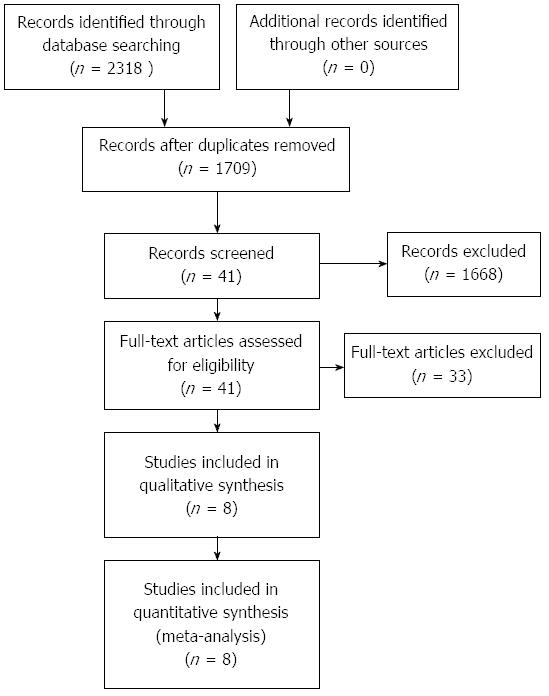

A total of 2318 articles were retrieved through the search strategy. Eight studies[2,11-13,24-27] including 1253 patients matched the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Details on the included studies are shown in Table 1. Five studies[2,11-13,24] compared patients with and without the bile leakage test, including 1032 patients (505 in the bile leakage test group and 527 in the control group). Two trials[25,27] compared a bile leakage test using indocyanine green solution with fluorescent imaging (ICGF Test) with a bile leakage test without fluorescent imaging (N-ICGF Test), including 161 patients (79 in the trial group and 82 in the control group). One study[26] compared a bile leakage test using fat emulsion (white test; injecting a fat emulsion solution through the cystic duct) with a test using saline solution, including 60 patients (30 in the white test group and 30 in the saline solution test group). These studies were published between 2000 and 2012. One trial[24] only enrolled liver donor patients and another[13] enrolled patients with tumor or hepatolithiasis; all remaining trials enrolled patients with a tumor. The quality assessment of RCTs and controlled clinical trials is displayed in Tables 2 and 3.

| Study | Design | Comparison | Material | Sample (trial:control) | Inclusion criteria | Liver disease | Country |

| Ijichi et al[11], (2000) | RCT | BL Test vs N-BL Test | Saline solution | 51:51 | Liver resection | Tumor | Japan |

| Liu et al[13], (2012) | RCT | BL Test vs N-BL Test | Fat emulsion | 53:54 | Liver resection | Tumor or hepatolithiasis | China |

| Li et al[12], (2009) | Controlled clinical trial | BL Test vs N-BL Test | Fat emulsion | 57:70 | Major liver resection | Tumor | Germany |

| Suehiro et al[24], (2005) | Controlled clinical trial | BL Test vs N-BL Test | ICG | 40:40 | Liver resection | Liver donor | Japan |

| Lam et al[2], (2001) | Controlled clinical trial | BL Test vs N-BL Test | Methylene | 304:312 | Liver resection | Tumor | Hong Kong |

| blue | |||||||

| Leelawat et al[26], (2012) | Controlled clinical trial | White Test vs Saline Solution Test | Fat emulsion | 30:30 | Liver resection | Tumor | Thailand |

| Sakaguchi et al[27], (2010) | Controlled clinical trial | ICGF Test vs N-ICGF Test | ICG | 27:32 | Liver resection | Tumor | Japan |

| Kaibori et al[25], (2011) | RCT | ICGF Test vs N-ICGF Test | ICG | 52:50 | Liver resection | Tumor | Japan |

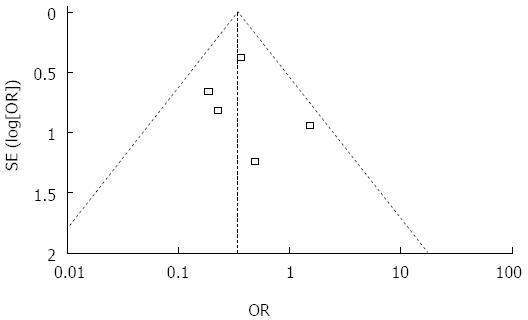

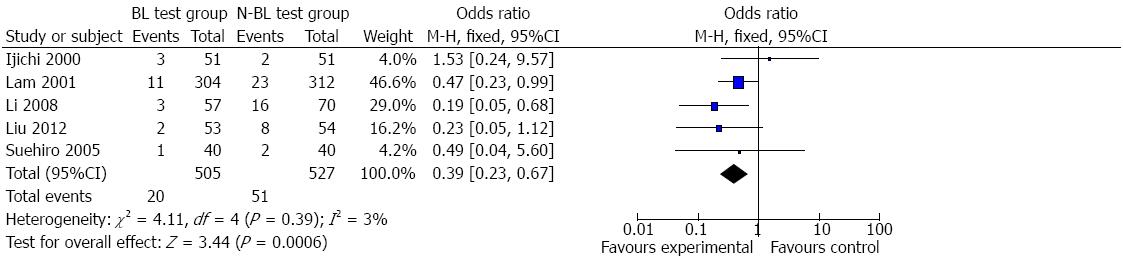

Bile leakage: Information on postoperative bile leakage was available for all five trials[2,11-13,24]. Funnel plot (Figure 2) did not demonstrate strong asymmetry. Meta-analysis indicated that the bile leakage test group had less postoperative bile leakage than the non-bile leakage test group (Figure 3) (RR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.23-0.67, P = 0.39, I2 = 3%). Clinical heterogeneity analysis found that one study[2] including a large sample of 616 patients was a retrospective study and the others were prospective. Meta-analysis of the other four trials also showed higher incidence of bile leakage in the non-bile leakage test group (RR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.15-0.70, P = 0.29, I2 = 20%).

Other complications: Four trials[11-13,24] reported the incidence of total complications, however, only data from three trials[11-13] could be used for analysis, and one trial[24] did not provide sufficient information on complications. There was no significant difference in the incidence of total complications (RR = 0.84, 95%CI: 0.63-1.13, P = 0.37, I2 = 0%). No significant heterogeneity was observed. Other complications such as wound infection, ileus, liver insufficiency, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, pulmonary disorder, and hepatic failure were reported and analyzed. Wound infection (RR = 1.83, 95%CI: 0.58-5.78, P = 0.94, I2 = 0%), pulmonary disorder (RR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.54-1.96, P = 0.87, I2 = 0%), and abdominal infection (RR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.61-3.55, P = 0.56, I2 = 0%) were reported in three studies[11-13] and no significant difference was observed between the bile leakage test group and non-bile leakage test group. Two studies[11,12] reported ileus (RR = 1.86, 95%CI: 0.24-14.24, P = 0.68, I2 = 0%) and liver insufficiency (RR = 1.18, 95%CI: 0.17-8.29, P = 0.21, I2 = 37%), and no significant difference was observed between the bile leakage test group and non-bile leakage test group. Intraperitoneal hemorrhage was reported in two studies[11,13] and there was no significant difference between the bile leakage test group and non-bile leakage test group (RR = 1.01, 95%CI: 0.18-5.71, P = 0.37, I2 = 0%). Two trials[12,13] reported liver failure, and meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the bile leakage test group and non-bile leakage test group (RR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.41-5.29, P = 0.76, I2 = 0%).

Bile leakage: Both of the studies[25,27] provided data on postoperative bile leakage. Meta-analysis of the two studies revealed that there was no significant difference between the ICGF test group and N-ICGF test group (RR = 0.13, 95%CI: 0.02-1.00, P = 0.64, I2 = 0%).

Other complications: There was no significant difference in total complications (RR = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.21-1.07; P = 0.21, I2 = 36%) between the ICGF test group and N-ICGF test group[25,27], nor in pleural effusion (RR = 1.78, 95%CI: 0.49-6.44, P = 0.73, I2 = 0%) or wound infection (RR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.09-2.09, P = 0.71, I2 = 0%).

Only one self-controlled study[26] compared the white test with the saline solution test. Only data on intraoperative bile leakage were provided and meta-analysis revealed that the white test had a higher rate of bile leakage points (RR = 2.38, 95%CI: 1.24-4.56, P = 0.009).

Other outcomes: These studies did not provide enough data on operation time, blood loss, postoperative hospital stay, or duration of drainage for analysis. The bile leakage test showed intraoperative bile leakage points on the hepatic resection plane in an average of 39.3% patients (range, 19.7%-80.8%). The postoperative bile leakage rate was 0%-5.9% after suturing. Among the bile leakage patients, 25 (41.0%) were treated conservatively; 12 (19.8%) underwent puncture drainage; 11 (18.0%) underwent endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; and 13 (21.2%) required reoperation (Table 4).

| Study | Intraoperative bile leakage | Postoperative bile leakage | Conservative treatment (n) | Puncture drainage (n) | ENBD (n) | Reoperation(n) |

| Ijichi et al[11], 2000 | 41.2% (21/51) | 5.9% (3/51) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liu et al[13], 2012 | 62.3% (33/53) | 3.8% (2/53) | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Li et al[12], 2009 | 71.4% (45/63) | 5.3% (3/57) | No description | No description | 1 | 2 |

| Suehiro et al[24], 2005 | No description | 2.5% (1/40) | No description | No description | No description | No description |

| Lam et al[2], 2001 | 19.7% (60/304) | 3.6% (11/304) | 7 | 11 | 6 | 10 |

| Leelawat et al[26], 2012 | 63.3% (19/30) | No description | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sakaguchi et al[27], 2010 | 29.6% (8/27) | 0% (0/27) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kaibori et al[25], 2011 | 80.8% (42/52) | 0% (0/52) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 39.3% (228/580) | 3.42% (20/584) | 25 (41.0%) | 12 (19.8%) | 11 (18.0%) | 13 (21.2%) |

Bile leakage is a common complication after hepatic resection and seriously affects postoperative quality of life, and also causes intra-abdominal infection and liver failure[13]. During the operation, it is difficult for surgeons to identify bile leakage by traditional methods such as the gauze test. Technical diligence in liver resection is required intraoperatively to minimize bile leakage. The bile leakage test is considered to be an effective method to prevent intraoperative bile leakage. The aim of the bile leakage test is to detect insufficiently closed stumps of bile ducts on the transected liver surface by elevating biliary pressure[24] and then the leakage site is sutured.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis and eight trials including three aspects of the bile leakage test were included. In the bile leakage test group vs non-bile leakage test group, studies involving the bile leakage test drew different conclusions. Three studies[2,12,13] showed that the bile leakage test decreased postoperative bile leakage, whereas two studies[11,24] showed no significant difference. Our meta-analysis showed that the bile leakage test group had a lower incidence of bile leakage than the non-bile leakage test group. Moreover, there was no significant difference in complications between the two groups. This suggests an effective and safe method for prevention of postoperative bile leakage. In the ICGF test group, ICG was injected into the biliary duct and then bound with proteins in bile[28]. The ICG-bile mixture can evoke fluorescent images that are obtained using an infrared camera system. Bile leakage can be easily detected by the extra-biliary fluorescent signal[25,27]. Meta-analysis found no difference in bile leakage rate and postoperative complications. Only one self-controlled study[26] compared the white test with the saline solution test and only positive rate of the intraoperative bile leakage test could be used for analysis. Meta-analysis found that the white test was superior for the detection of bile leakage compared with the saline solution test. However, the limitations of the number of trials (only one) may have affected our results and interpretation. Therefore, our results showed that the bile leakage test reduced postoperative biliary leakage, and considering the solution used in the test, fat emulsion may be more effective than saline solution.

To perform the bile leakage test, incidental cholecystectomy and cystic duct exploration are always necessary. One meta-analysis[29] reported increased morbidity in patients undergoing incidental cholecystectomy. However, in our meta-analysis, total complications, wound infection, ileus, liver insufficiency, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, pulmonary disorder, and hepatic failure showed no significant difference. The detection of bile leakage depends on elevated pressure by injecting solution into the biliary tract, however, excessive bile duct pressure could lead to regurgitation of bacteria and induce cholangitis and abdominal infection[15,16]. Although abdominal infection did occur in some trials, our meta-analysis showed that the bile leakage test did not increase the risk of abdominal infection. Therefore, the bile leakage test is a safe technique and does not cause additional complications.

In all the included studies, the bile leakage test detected leakage in an average of 39.3% patients (range, 19.7%-80.8%). After prophylactic closure of the leaking bile duct stump, bile leakage occurred in only an average of 3.42% of patients, which was significantly lower than before. This suggests that the bile leakage test can reduce bile leakage in liver resection, but it does not completely eliminate it. Several reasons could explain this. First, we need to consider the lack of refinement of surgical techniques. For example, the pressure on the bile duct was not high enough so that bile leakage was not observed during the operation. Inadequate suturing of the defect[2] also could lead to bile leakage. Second, minor bile ducts in the wound surface of the liver were obstructed by microliths, and the bile leakage was formed when the microliths dropped off after the operation[13]. Third, there were defects in the technique of the bile leakage test. Parts of the leaky bile ducts were not in communication with the biliary tree, therefore, the leakage sites could not be identified through the use of an intraoperative bile leakage test[13]. Moreover, solutions such as ICG and methylene blue have the drawback of staining surrounding tissues, and saline solution has poor sensitivity. These drawbacks make precise localization or identification of multiple sites of leakage difficult[12]. However, the white fat emulsion can be easily washed out from the bile ducts[26] and it does not contaminate the surface of the wound, and it can be used repeatedly in tests. This may be the reason why the white test can decrease bile leakage more than the saline solution test can.

However, some patients without the bile leakage test did not develop bile leakage, for the following reasons. First, partial minor leakage points can be closed spontaneously. Second, bile leakage from small biliary stumps with some communication to the main biliary tree would usually close spontaneously, with the restoration of peristalsis and papillary function[11]. Thus, the bile leakage test could not completely eliminate bile leakage, but just decrease it.

This review had some limitations. The first concerns the small number of RCTs included, and we also included non-randomized trials. Second, incomplete reporting of important methodological issues, such as randomization process and blinding assessment of trial quality, raises doubts about the adequate power of these studies. Third, the heterogeneity of the patients in the included trials may have influenced the conclusions because some trials included liver tumor patients and only one study included living donors. To overcome these limitations, more RCTs should be conducted with large numbers of patients to achieve a sufficient level of statistical power for accurate evaluation of the bile leakage test.

In conclusion, this review provides the best available evidence for the safety and efficacy of the bile leakage test. On the basis of this evidence, the bile leakage test appears to reduce the incidence of postoperative bile leakage and does not increase the incidence of other complications. In addition, fat emulsion may be the best choice of solution for use in the bile leakage test. Further trials are required to assess the role of the bile leakage test in liver resection patients.

Liver resection is an important treatment method for liver diseases, especially for liver cancer. Bile leakage is a common complication after hepatic resection and seriously affects patients’ postoperative quality of life. Therefore, it is important to prevent bile leakage in liver resection. Many methods have been introduced to prevent bile leakage after liver transection and the bile leakage test is a common approach.

Several trials have evaluated the safety and efficacy of the bile leakage test; however, the results of this technique remain inconsistent. The authors conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the bile leakage test in liver resection.

The authors have provided the best available evidence for the safety and efficacy of the bile leakage test. This meta-analysis found that the bile leakage test lowered the incidence of postoperative bile leakage and could not increase the incidence of other complications. In addition, fat emulsion may be the best choice of solution for use in the bile leakage test.

The study results suggest that the bile leakage test is an effective and safe method that could be used in preventing bile leakage after liver resection.

The bile leakage test is a common approach to reduce postoperative bile leakage. With this technique, after cholecystectomy and liver resection, a catheter is inserted through the cystic duct into the common bile duct and the distal common bile duct is occluded. Solution is slowly injected into the biliary tree and a clinical judgment is then made as to whether a bile leak is present on the transected surface of the liver. If so, the bile leak site will be closed steadily beforehand to avoid bile leakage.

The authors present a meta-analysis of the literature describing feasibility, safety and efficacy of a method to avoid complications after hepatic surgery, the so-called bile leakage test. The topic of the article is important for researchers and the literature analysis reported is interesting.

P- Reviewers: Giraldi G, Plaszewski M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Capussotti L, Ferrero A, Viganò L, Sgotto E, Muratore A, Polastri R. Bile leakage and liver resection: Where is the risk? Arch Surg. 2006;141:690-694; discussion 695. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 156] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lam CM, Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST. Biliary complications during liver resection. World J Surg. 2001;25:1273-1276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guillaud A, Pery C, Campillo B, Lourdais A, Sulpice L, Boudjema K. Incidence and predictive factors of clinically relevant bile leakage in the modern era of liver resections. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15:224-229. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Lai EC, Wong J. Biliary complications after hepatic resection: risk factors, management, and outcome. Arch Surg. 1998;133:156-161. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Nagano Y, Togo S, Tanaka K, Masui H, Endo I, Sekido H, Nagahori K, Shimada H. Risk factors and management of bile leakage after hepatic resection. World J Surg. 2003;27:695-698. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 141] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tanaka S, Hirohashi K, Tanaka H, Shuto T, Lee SH, Kubo S, Takemura S, Yamamoto T, Uenishi T, Kinoshita H. Incidence and management of bile leakage after hepatic resection for malignant hepatic tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:484-489. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 135] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamashita Y, Hamatsu T, Rikimaru T, Tanaka S, Shirabe K, Shimada M, Sugimachi K. Bile leakage after hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 2001;233:45-50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 265] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kubo S, Sakai K, Kinoshita H, Hirohashi K. Intraoperative cholangiography using a balloon catheter in liver surgery. World J Surg. 1986;10:844-850. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Figueras J, Llado L, Miro M, Ramos E, Torras J, Fabregat J, Serrano T. Application of fibrin glue sealant after hepatectomy does not seem justified: results of a randomized study in 300 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:536-542. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Noun R, Singlant JD, Belghiti J. A practical method for quick assessment of bile duct patency during hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:77-78. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Ijichi M, Takayama T, Toyoda H, Sano K, Kubota K, Makuuchi M. Randomized trial of the usefulness of a bile leakage test during hepatic resection. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1395-1400. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li J, Malagó M, Sotiropoulos GC, Lang H, Schaffer R, Paul A, Broelsch CE, Nadalin S. Intraoperative application of “white test” to reduce postoperative bile leak after major liver resection: results of a prospective cohort study in 137 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:1019-1024. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Liu Z, Jin H, Li Y, Gu Y, Zhai C. Randomized controlled trial of the intraoperative bile leakage test in preventing bile leakage after hepatic resection. Dig Surg. 2012;29:510-515. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ochiai T, Ikoma H, Inoue K, Murayama Y, Komatsu S, Shiozaki A, Kuriu Y, Nakanishi M, Ichikawa D, Fujiwara H. Intraoperative real-time cholangiography and C-tube drainage in donor hepatectomy reduce biliary tract complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2159-2164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Huang T, Bass JA, Williams RD. The significance of biliary pressure in cholangitis. Arch Surg. 1969;98:629-632. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yoshimoto H, Ikeda S, Tanaka M, Matsumoto S. Relationship of biliary pressure to cholangiovenous reflux during endoscopic retrograde balloon catheter cholangiography. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:16-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Higgins JPT GSe. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011; Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16777] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16230] [Article Influence: 1082.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Jadad AR, Enkin MW. Randomised Controlled Trials. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: BMJ Books 2007; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Induction of clinical response and remission of inflammatory bowel disease by use of herbal medicines: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5738-5749. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Wells GA SB, O’Connell D, Robertson J, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical epidemiology/oxford.htm. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Zhao XD, Cai BB, Cao RS, Shi RH. Palliative treatment for incurable malignant colorectal obstructions: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5565-5574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Deeks JJ HJ, Altman DG, editors . Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration 2011; Available from: http://www.cochranehandbood.org. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Suehiro T, Shimada M, Kishikawa K, Shimura T, Soejima Y, Yoshizumi T, Hashimoto K, Mochida Y, Maehara Y, Kuwano H. In situ dye injection bile leakage test of the graft in living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;80:1398-1401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kaibori M, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, Kwon AH. Intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescent imaging for prevention of bile leakage after hepatic resection. Surgery. 2011;150:91-98. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Leelawat K, Chaiyabutr K, Subwongcharoen S, Treepongkaruna SA. Evaluation of the white test for the intraoperative detection of bile leakage. HPB Surg. 2012;2012:425435. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sakaguchi T, Suzuki A, Unno N, Morita Y, Oishi K, Fukumoto K, Inaba K, Suzuki M, Tanaka H, Sagara D. Bile leak test by indocyanine green fluorescence images after hepatectomy. Am J Surg. 2010;200:e19-e23. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ishizawa T, Tamura S, Masuda K, Aoki T, Hasegawa K, Imamura H, Beck Y, Kokudo N. Intraoperative fluorescent cholangiography using indocyanine green: a biliary road map for safe surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:e1-e4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 163] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Warschkow R, Tarantino I, Ukegjini K, Beutner U, Güller U, Schmied BM, Müller SA, Schultes B, Thurnheer M. Concomitant cholecystectomy during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese patients is not justified: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2013;23:397-407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |