Published online Nov 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16349

Revised: May 13, 2014

Accepted: July 15, 2014

Published online: November 21, 2014

Intestinal occlusion by internal hernia is not a rare complication (0.2%-5%) after Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y-GBP (LGBP) with higher morbidity and mortality related to mesenteric vessels involvement. In our Center, from October 2009 to April 2013 we have had 17 pts treated for internal hernia on 412 LGBP (4.12%). Clinical case: 28-year-old woman, operated of LGBP (BMI = 49; co-morbidity: diabetes mellitus and arthropathy) about 10 mo before, was affected by recurrent abdominal pain with alvus alteration lasting for a week. After vomiting, she went to first aid Unit of a peripheric hospital where she made blood tests, RX and US of abdomen that resulted normal so she was discharged with flu like syndrome diagnosis. After 3 d the patient contacted our Center since her symptoms got worse and was hospitalized. Blood tests showed an alteration of hepatic enzymes and amylases. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed the presence of fluid in peri-splenic, peri-hepatic areas and in pelvis and a “target like imagine” of “clustered ileal loops” with a superior mesenteric vein (SMV) thrombosis involving the Portal Vein. During the operation, we found a necrosis of 80 cm of ileus (about 50 cm downstream the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis) due to an internal hernia through Petersen’s space causing a SMV thrombosis. The necrotic bowel was removed, the internal hernia was reduced and Petersen’ space was sutured by not-absorbable running suture. An anticoagulant therapy was begun in the post-operative time and the patient was discharged after 28 d. Conclusions: The internal hernia diagnosis is rarely confirmed by preoperative exams and it is obtained in most cases by laparoscopy but the improvement of technologies and the discover of “new” CT signs interpretation can address to an early laparoscopic treatment for high suspicion cases.

Core tip: We report a rare case of patients with a small bowel infarction due to Portomesenteric Vein thrombosis following an Internal Hernia through the Petersen’s space as a complication of Roux-en-Y laparoscopic gastric bypass and the different computed tomography physiological and pathological “uncommon signs” that must be searched and recognized. With the progressive diffusion of Bariatric Surgery, it is very important that all digestive surgeons and emergency physicians have knowledge of these rare but serious complication caused by internal hernia because these patients could be also hospitalized in urgency in whatever Surgery Unit that doesn’t commonly deal with obesity surgery.

- Citation: Fabozzi M, Brachet Contul R, Millo P, Allieta R. Intestinal infarction by internal hernia in Petersen’s space after laparoscopic gastric bypass. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(43): 16349-16354

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i43/16349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16349

Internal hernia after Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y-GBP (LGBP) is not a rare complication (1%-5% of patients)[1]. It can also occur after gastric or colonic surgery. After gastric bypass the conditioning factors may be: (1) more difficult exposure of small bowel and related mesentery in laparoscopy; (2) more complicated laparoscopic suture of mesentery; (3) less post-operative adhesions in Laparoscopy; (4) weight loss reduces intraperitoneal fat, with enlargement of mesenteric or mesocolic defects; and (5) an additional possible site of herniation in retrocolic compared to antecolic gastric bypass (GBP).

The potential sites of Internal Hernia depend from the alimentary ROUX-limb positioning. The retrocolic alimentary limb shows three sites: through the transverse mesocolon, trough the Petersen’s space and the jejunojejunostomy mesentery. The antecolic antegastric alimentary limb instead, shows only 2 sites and for this reason it is the most practiced: through the jejunojejunostomy mesentery and through the Petersen’s space.

According to the data of Literature, this complication usually occurs about a year after Gastric Bypass[2-4] and may lead to intestinal perforation by intestinal ischemia in 9.1% and death in 1.6%[5]. In fact, pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic surgery may be a factor favouring thrombosis in the mesenteric venous system especially in obese patients.

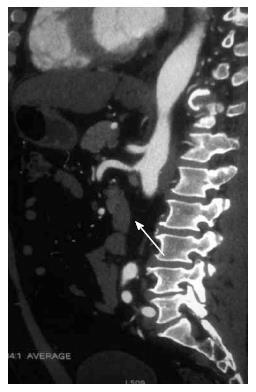

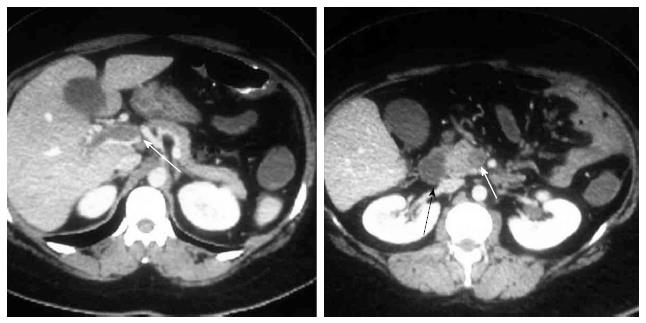

The preoperative diagnosis is very difficult since the symptoms are not specific or blurred. Generally, the patients accuse vague abdominal pain with nausea and sometimes vomiting. The laboratory exams are not specific too. Sometimes it could be a modest alteration of transaminases and amylase[6]. The only significant instrumental exam to discover internal hernia after GBP is the Abdominal CT that can show specific physiological (Table 1) and pathological (Table 2)[7] signs that must be searched and recognized (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

| 1 | The jejuno-jejunal anastomosis (and the biliary limb) on the left side of abdomen |

| 2 | Absence of loops behind the SMA |

| 3 | Absence of loops in mesocolic and mesenteric space |

| 4 | Mesenteric fan and jejuno-jejunal anastomosis deployed on the left side of abdomen |

| SIGNS | Sensitivity% | Specificity% |

| Swirled mesentery | 61-83 | 67-94 |

| Mushroom | 33-72 | 89-100 |

| Hurricane eye | 6-17 | 100 |

| Small-bowel obstruction | 11-39 | 83-94 |

| Clustered loops | 6-17 | 72-83 |

| Small-bowel behind superior mesentery artery | 0-44 | 89-100 |

| Overall impression | 56-78 | 78-89 |

| Right-sided anastomosis (or mesenteric fan deployed on the right side of abdomen) | 6-11 | 100 |

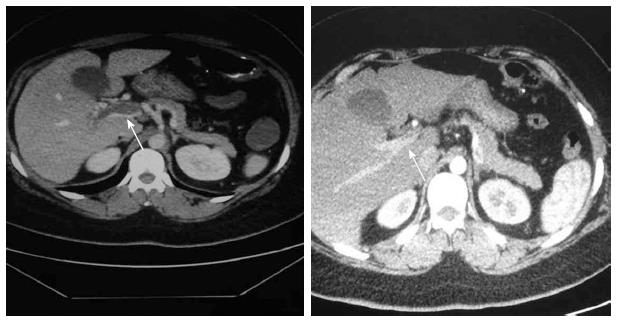

A 28-year-old woman operated of GBP for morbid obesity 10 mo before (BMI = 49; comorbidity: diabetes mellitus and arthropathy), presented recurrent abdominal pain lasting for a week, with alvus alteration and two episodes of vomiting in the last two days. She went in the first Aid Unit of a peripheric hospital where she made Blood Tests, Radiography and Ultrasonography of abdomen that resulted normal. She was discharged with flu like syndrome diagnosis and with painkillers and antiemetic therapy. Unfortunately, the symptoms worsened so she was hospitalized in our Center 3 d after. The blood test showed an alteration of hepatic enzymes and amylases so she was submitted to Abdominal CT scan that showed some fluid in peri-splenic, peri-hepatic areas and in pelvis, a “target like imagine” of “clustered ileal loops (Figure 6), a superior mesenteric vein (SMV) thrombosis involving the Portal Vein (Figure 7). The patient underwent to urgent laparotomy. A necrosis of 80 cm of ileum (Figure 8) (about 50 cm downstream the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis) due to an internal hernia through Petersen” s space and a Superior Mesenteric Vein thrombosis were found. The necrotic bowel was removed and primary ileo-ileal anastomosis was performed. The internal hernia was reduced and the Petersen’ space was sutured by not-absorbable running suture. Before and after the operation the patient was submitted to I.V. anticoagulant therapy that was continued until the last days before discharge and replaced by an oral anticoagulant at home. The patient was discharged after 28 d with oral anticoagulant therapy.

The post-operative follow-up was normal and no coagulation disorders of the patient was found. The abdominal CT in the second month showed a recanalization of SMV and an almost complete recanalization of Portal Vein (Figure 9). The one year follow-up after thrombosis was regular.

Deep venous thrombosis of intestinal vessels is a severe even if infrequent complication after abdominal operations and was first reported in 1895 by Elliot[8]. It is the cause of acute mesenteric ischemia in 5%-15% of patients[9]. From 1935 the mortality rate (about 34%)[10] is drastically decreased thanks to the improvement in diagnostic and therapeutic field (use of anticoagulants, thrombolytic agents and endovascular techniques).

Laparoscopic surgery may predispose to early deep venous thrombosis (in the first p.o. mounth) due to many factors such as: pneumoperitoneum that increases the abdominal pressure and slows the venous return to the heart, hypercapnia that induces mesenteric vasoconstriction and coagulation alterations.

The elevated CO2 blood levels in particular, cause sympathetic vasoconstriction responsible for increase in peripheral resistors, in mean arterial blood pressure, in pulmonary artery and capillary wedge pressure.

Another factor determining increased peripheral resistors is the elevated vasopressin rate caused by hypercapnia[11,12].

The tissue factor secretion induced by surgical trauma may cause SMV thrombosis in predisposed patients with undiagnosed coagulative disorders. This hypothesis is confirmed by high rate of SMV thrombosis during laparoscopy for colonic inflammatory diseases such as diverticulitis. In literature, it has also been described the influence of laparoscopy on coagulations favouring a prothrombotic state[13].

In our case moreover the Portomesenteric thrombosis has a cause different from that one previously reported: the developing of an internal hernia about 10 mo after Gastric Bypass for morbid obesity. The presence of coagulation abnormalities was excluded by post-operative blood tests.

Intestinal infarction presents aspecific symptoms that make the clinical diagnosis very difficult therefore the only suspicion must be essential to address diagnostic exams and early treatments. Blood tests may show leukocytosis, elevated creatinine kinase, amylase, and lactate[6].

The gold standard for diagnosis is CT scanning which has a sensitivity of 90% (7). CT signs suggesting SMV thrombosis are SMV dilation surrounded by hyper-dence tissue, edematous bowel or mesenteric fat stranding.

It’s important to know which signs must be searched and all types of CT reconstruction (vascular MIP) must be required to discover these signs. The surgeon or radiologist must know the normal CT signs of patients after Gastric Bypass (Table 1) and research the nine pathological CT signs of internal hernia of which the “hurricane eye” and “the right-sided anastomosis” (with its mesentery) present the best specificity (Table 2). However, the combination of more signs can improve the suspicion index.

Other diagnostic exams includes angiography, trans-abdominal doppler ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging but these techniques don’t show any real advantages vs CT scan[11,14].

In our patient, the diagnosis of intestinal infarction by internal hernia was suspected by CT and confirmed by operation. Diagnostic laparoscopy is not recommended by many Authors for a suspected SMV thrombosis, so we decided to perform in our patient a laparotomy to avoid the increase in abdominal pressure caused by pneumoperitoneum that could further slow the venous return and worsen the intestinal ischemia[15,16].

However, in some cases diagnostic laparoscopy is preferred to exclude bowel ischemia and avoid a non-therapeutic laparotomy[9]. CT scan in fact is useful for the diagnosis of SMV thrombosis, but it is not able to determine the extent of bowel ischemia[17].

In our patient, after the laparotomy, we found an internal hernia through the Petersen's space that caused the venous outflow reduction in Superior Mesenteric Vein resulting in Portomesenteric thrombosis and jejunal loop necrosis[18].

In conclusion, the internal Hernia is an important complication that is difficult to identify and usually occurs about a year after surgery. Patient’s medical (and surgical) history is the key for its diagnosis and treatment. Recurrent pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea are nonspecific symptoms and diagnosis is rarely confirmed by preoperative exams. High index of suspicion of internal hernia especially after laparoscopy in particular in GBP operations, is needed for early diagnosis and treatment. The improvement of technologies can show high suspicion CT “signs” for internal hernia but the diagnosis was obtained in most cases by laparoscopy. For this reason, early laparoscopic exploration in patient operated of GBP presenting symptoms of bowel obstruction, is mandatory. If the diagnosis of intestinal infarction is clear by CT scan, it is recommended to make open surgical procedure to avoid the worsening of thrombosis also in other vascular districts in post-operative time.

With the progressive diffusion of Bariatric Surgery in the world, it is very important that all digestive surgeons and emergency physicians have knowledge of these rare but serious complications caused by internal hernias because these patients with nonspecific symptoms, could be also hospitalized in emergency in whatever Surgery Unit also without experience in obesity surgery.

Recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea are typical but nonspecific (in early state are blurred) symptoms of internal hernia.

Patient’s medical history (gastric bypass operation about 1 year before) can address the physician to internal hernia suspicion and lead to diagnosis and early treatment.

In the early stages the symptoms may be blurred and confused with viral gastrointestinal syndrome.

The laboratory exams are not specific too, showing sometimes a modest alteration of transaminases, amylase and lactate.

The gold standard diagnostic exam is the Abdominal computed tomography (CT) (90% sensitivity) with all types of digital reconstructions (vascular MIP) which may show specific physiological and pathological uncommon CT signs (if searched and recognized) such as: “hurricane eye” and “the right-sided anastomosis”, “target like imagine”, “clustered ileal loops”, etc.

The combination of more CT signs may improve or in some cases may confirm the suspicion index.

The patient was treated by intestinal resection and closure of Petersen’ space by not-absorbable running suture and by anticoagulant therapy for Portomesenteric Thrombosis before and after the operation.

In all obese patient operated of Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y-GBP, it is important to consider each abdominal symptom (especially if recurrent) that must be investigated by CT scan with all digital reconstructions to exclude internal hernia.

This is an isolated case but the progressive diffusion of Bariatric Surgery suggests the importance for all digestive surgeons and emergency physicians to have a knowledge of this rare complication and of these CT signs to diagnose it because obese patients could be hospitalized in whatever First Aid Unit also without experience in bariatric surgery.

The case is quite interesting and deserves to be reported.

P- Reviewer: De Palma R, Pellicano R S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Steele KE, Prokopowicz GP, Magnuson T, Lidor A, Schweitzer M. Laparoscopic antecolic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with closure of internal defects leads to fewer internal hernias than the retrocolic approach. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2056-2061. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Garza E, Kuhn J, Arnold D, Nicholson W, Reddy S, McCarty T. Internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Surg. 2004;188:796-800. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ahmed AR, Rickards G, Husain S, Johnson J, Boss T, O’Malley W. Trends in internal hernia incidence after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1563-1566. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Husain S, Ahmed AR, Johnson J, Boss T, O’Malley W. Small-bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Arch Surg. 2007;142:988-993. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Higa KD, Ho T, Boone KB. Internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: incidence, treatment and prevention. Obes Surg. 2003;13:350-354. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 301] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cho M, Carrodeguas L, Pinto D, Lascano C, Soto F, Whipple O, Gordon R, Simpfendorfer C, Gonzalvo JP, Szomstein S. Diagnosis and management of partial small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic antecolic antegastric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:262-268. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lockhart ME, Tessler FN, Canon CL, Smith JK, Larrison MC, Fineberg NS, Roy BP, Clements RH. “Internal Hernia After Gastric Bypass: Sensitivity and Specificity of Seven CT Signs with Surgical Correlation and Controls. A. m J Roentgenol. 2007;188:745-750. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 134] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elliot JW. II. The Operative Relief of Gangrene of Intestine Due to Occlusion of the Mesenteric Vessels. Ann Surg. 1895;21:9-23. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | James AW, Rabl C, Westphalen AC, Fogarty PF, Posselt AM, Campos GM. Portomesenteric venous thrombosis after laparoscopic surgery: a systematic literature review. Arch Surg. 2009;144:520-526. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 110] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Warren S, Eberhard TP. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1935;61:102-121. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Sucandy I, Gabrielsen JD, Petrick AT. Postoperative mesenteric venous thrombosis: Potential complication related to minimal access surgery in a patient with undiagnosed hypercoagulability. N Am J Med Sci. 2010;2:329-332. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Poultsides GA, Lewis WC, Feld R, Walters DL, Cherry DA, Ruby ST. Portal vein thrombosis after laparoscopic colectomy: thrombolytic therapy via the superior mesenteric vein. Am Surg. 2005;71:856-860. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Johnson CM, de la Torre RA, Scott JS, Johansen T. Mesenteric venous thrombosis after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1:580-582; discussion 582-583. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Swartz DE, Felix EL. Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. JSLS. 2004;8:165-169. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Cho YP, Jung SM, Han MS, Jang HJ, Kim JS, Kim YH, Lee SG. Role of diagnostic laparoscopy in managing acute mesenteric venous thrombosis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:215-217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chong AK, So JB, Ti TK. Use of laparoscopy in the management of mesenteric venous thrombosis. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1042. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Merali HS, Miller CA, Erbay N, Ghosh A. Importance of CT in Evaluating Internal Hernias after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. J Radiol Case Rep. 2009;3:34-37. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Kimball R, Kurian A, Antanavicus G, Bonnani F. Superior mesenteric venous thrombosis related to Peterson’s hernia. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:e56-e57. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |