Published online Nov 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16707

Revised: July 13, 2014

Accepted: August 13, 2014

Published online: November 28, 2014

AIM: To investigate how complete laparoscopic anterior resection with natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE), as a novel minimally invasive surgery, compares to conventional laparoscopic surgery.

METHODS: Twenty patients who underwent complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE and 50 patients who underwent laparoscopic assisted anterior resection by the conventional method between 2011 and 2012 were studied. Selection for complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE was decided on the basis of tumor size, localization of the tumor, and body mass index. Outcomes related to surgery, including operation time, postoperative wound pain, hospital stay after surgery, the number of totally dissected lymph nodes, postoperative complications (suture failure and wound infection), and anal function, were reviewed retrospectively. Anal function was assessed at 3 and 6 mo after surgery using the Wexner fecal incontinence scoring system.

RESULTS: Complete laparoscopic resection with NOSE was performed to completion in all 20 patients. There was no patient emergency that required conversion to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery. The comparison between complete laparoscopic resection with NOSE and conventional laparoscopic surgery showed no significant differences in the maximal diameter of the tumor, number of totally dissected lymph nodes, bleeding volume, mean operation time, time to start of oral ingestion, postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative complications. On the other hand, with regard to pain after epidural anesthesia, the total usage of analgesia in this novel surgical technique was 1.85 ± 1.8 times, whereas it was 5.89 ± 2.86 in conventional laparoscopic surgery (P < 0.001). The postoperative pain period was 1.9 ± 1.9 d in this novel surgical technique, whereas it was 3.43 ± 1.41 d in conventional laparoscopic surgery (P < 0.004). In complete laparoscopic surgery with NOSE, the mean postoperative follow-up period was 20 mo (range: 12-30 mo). Neither local recurrence nor remote metastasis was observed during the follow-up period.

CONCLUSION: Complete laparoscopic anterior resection using NOSE does not require any incision and has excellent cosmetic properties, with mitigated postoperative pain.

Core tip: Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) has been reported as a less invasive surgery to avoid the problems arising from small incisions. In this study, we present details of a surgical technique for NOSE and the outcomes of complete laparoscopic anterior resection using NOSE are compared with conventional laparoscopic anterior resection. Complete laparoscopic anterior resection using NOSE has more advantages in terms of cosmetic outcomes and mitigating postoperative pain compared with conventional laparoscopic anterior resection. Based on our study, we consider complete laparoscopic anterior resection using NOSE as an acceptable and novel minimally invasive surgery.

- Citation: Hisada M, Katsumata K, Ishizaki T, Enomoto M, Matsudo T, Kasuya K, Tsuchida A. Complete laparoscopic resection of the rectum using natural orifice specimen extraction. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(44): 16707-16713

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i44/16707.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16707

With the recent advances in minimally invasive surgery, laparoscopic anterior resection for rectal cancer has become a common practice. However, an incision of about 5-6 cm is still made in the abdomen for resection of the lesion or insertion of the anvil head of the automatic anastomosis device. This incision, though small, carries risks of postoperative wound pain, infections, adhesions after surgery, or abdominal incisional hernia. For this reason, an even less minimally invasive surgical technique is required. In such a situation, natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) has been introduced as a less invasive surgery to solve the problems arising from small incisions. However, these surgical techniques have not yet become widespread.

Therefore, we have performed complete laparoscopic anterior resection in 20 patients through transanal extraction of the lesion without making any incision in the abdomen, and herein describe the surgical techniques and outcomes of this treatment.

The ethics committee of Tokyo Medical University Hospital approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from patients who would receive complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE. Patients diagnosed with rectal cancer were selected for complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE using several criteria. The indications for complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE were as follows: (1) tumor located at the distal side of the sigmoid colon to the upper side of the rectum; (2) a tumor diameter less than 5 cm and no serosal exposure, as evaluated by computed tomography; (3) lymph node metastasis less than cN1; and (4) no bulky mesorectum, as evaluated by a body mass index less than 30 kg/m2. A massive tumor, surrounding lymph nodes depicted on CT, or obese patients were excluded. A team that was proficient in various laparoscopic colorectal procedures at our hospital since 2004 performed all the operations. NOSE surgery was performed since 2010. If drawing the resected bowel intracorporeally was impossible or critical damage to the residual rectum occurred during the drawing, the operative procedure was converted to conventional laparoscopic surgery using the double stapling technique or to open surgery. All patients underwent oral magnesium citrate bowel preparation twice, 2 d before the operation. Twenty patients who underwent complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE and 50 patients who underwent laparoscopic assisted anterior resection by the conventional method between 2011 and 2012 were studied. Parameters including the operation time, postoperative wound pain, hospital stay after surgery, the number of totally dissected lymph nodes, postoperative complications, and anal function were evaluated. The anal function was assessed at 3 and 6 mo after surgery using the Wexner fecal incontinence scoring system. Statistical differences were examined using the t-test and Fisher’s χ2 test. A P value < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. The statistical analysis software used was Dr. SPSS II for Windows.

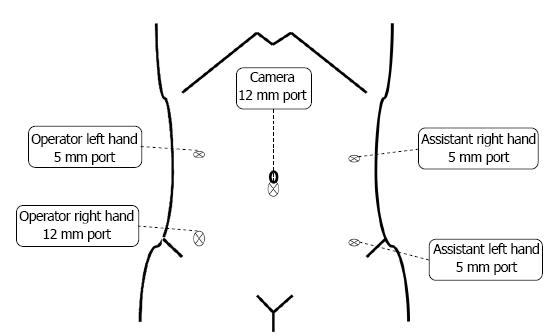

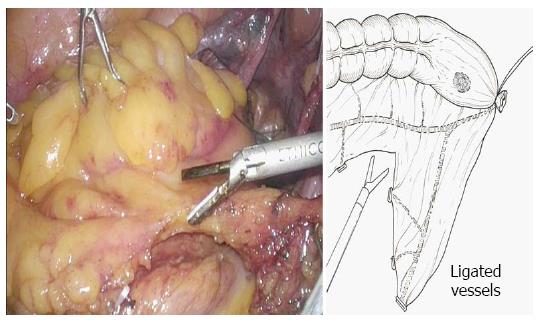

Five ports were created (Figure 1), and a pneumoperitoneum was created at 8-10 mmHg. One 12 mm camera port was inserted in the umbilical region or its adjacent area, another 12 mm port was used for the lower right abdomen, and 5 mm ports for the right and left upper abdomen and lower left abdomen were created. The mesosigmoid adjacent to the right common iliac artery was exfoliated from the inside. Exfoliation was continued cephalad, and the inferior mesenteric root was identified. To treat the inferior mesenteric artery, high ligation was performed; however, in some cases, the left colic artery was preserved by low ligation, depending on the stage of progression. The back side of the mesentery was exfoliated toward the outside as usual, and the lateral side of the sigmoid colon was exfoliated and communicated with the medial exfoliated layer. The descending colon should be manipulated as much as possible; otherwise the transanal extraction of the bowel becomes difficult or the tension after anastomosis may cause the risk of suture failure. At this time, the oral dissection line at 10 cm or more from the tumor is determined, as the guidelines indicate, to facilitate transanal extraction, and the marginal artery is totally dissected in a preserving manner, confirming the blood flow in the reconstruction bowel. The mesentery is dissected along the superior rectal artery and vein (Figure 2), and the oral dissection line is confirmed to sufficiently reach the pelvic floor.

Although it depends on the position of the tumor, the rectum is exfoliated sufficiently measuring 5 cm or longer from the tumor toward the anus. The dissection line of the bowel towards the anal side is determined and e trimming treatment of the mesorectum is performed.

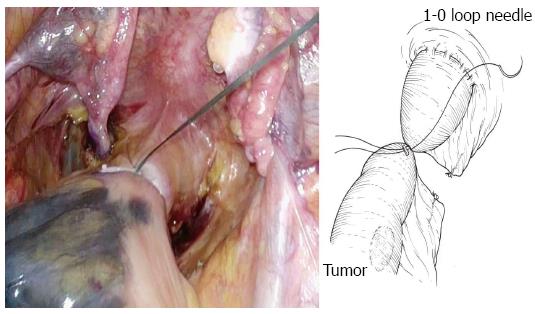

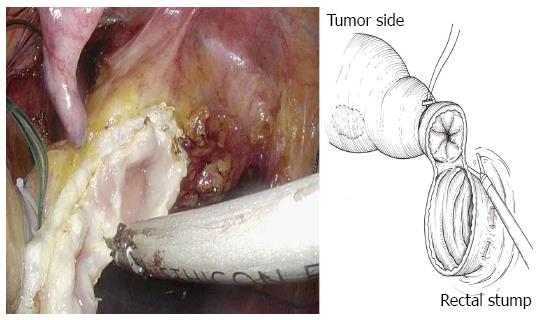

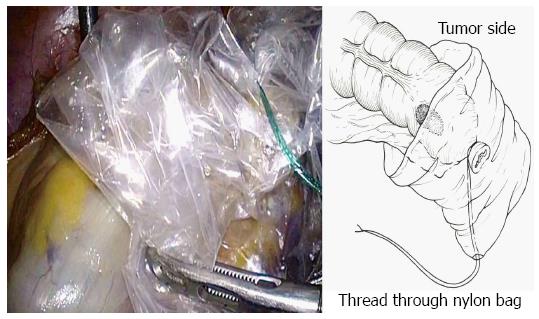

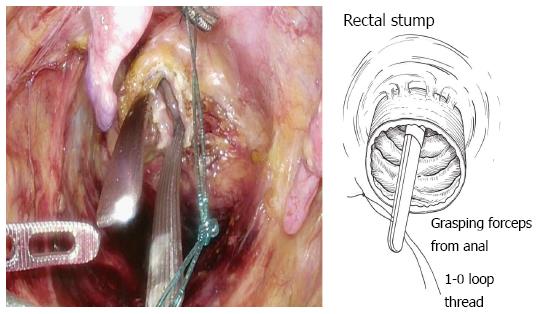

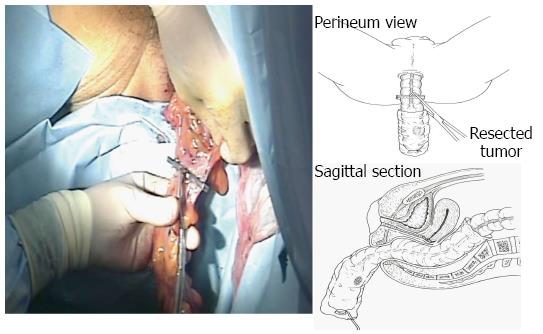

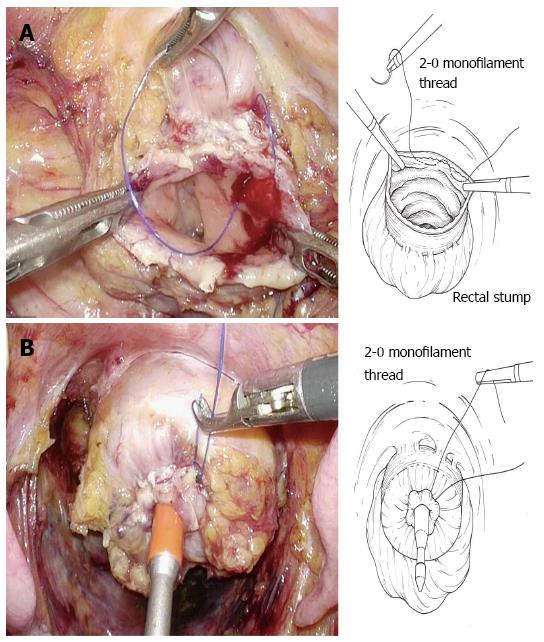

The bowel should be closed at the tumor towards the anal side with a 1-0 loop needle. First, the needle is inserted in the anterior wall of the bowel up to the seromuscular level, and turned to the posterior wall of the bowel. Seromuscular suturing is performed in the contralateral bowel, and the closing ligation is made through the loop. After tightening the loop, a Hem-o-lok clip is attached to the thread on the needle side and the bowel side is tightened for bondage (Figure 3). Rectal irrigation is performed from the anus with 500 mL of physiological saline containing povidone-iodine, and then the rectum is opened by laparosonic coagulating shears (LCS) (Figure 4). A nylon bag is then inserted to protect the tumor from the 12 mm port in terms of implantation or infections, and a 1-0 loop needle thread is pierced through it (Figure 5). To exteriorize the resected bowel, the straight grasping forceps are inserted transanally, followed by grasping a 1-0 loop thread, and drawing it into the residual rectum (Figure 6). In doing this, butyl scopolamine is administered intravenously, if necessary, to prevent the residual rectum from developing a spasm. The tumor is removed and the bowel is reconstructed from the body transanally. The tumor is dissected towards the oral side and the marginal artery is treated by inserting the anvil head of the automatic anastomosis device, repositioning the reconstructed bowel inside the body cavity (Figure 7). After sufficient irrigation of the rectal stump and pelvic cavity, purse-string suturing of the rectal stump with a 2-0 monofilament is performed laparoscopically, and then the anvil from the rectum is inserted and ligated for closure, keeping the central rod out (Figure 8A and B). When reefing of the rectal stump seems insufficient, occasionally additional reefing may be performed with an end loop. Finally, after sufficient irrigation of the pelvic cavity, anastomosis is performed with the single staple technique (SST), using an automatic anastomosis device.

Information concerning the 20 patients undergoing this surgical technique is shown in Table 1. Patients comprised 12 men and 8 women. No patient required conversion to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery. The maximal diameter of the tumor ranged from 10 mm to 50 mm, with a mean of 27 ± 9 mm. The comparison with conventional laparoscopic surgery is shown in Table 2. In laparoscopic surgery, the tumor diameter ranged from 10 mm to 90 mm, with a mean of 38.5 ± 18 mm. Although there was no significant difference between the new surgical technique and laparoscopic surgery, the tumor diameter was slightly smaller. The number of totally dissected lymph nodes was 17.7 ± 7.7 in the new surgical technique, whereas it was 17.5 ± 8.8 in conventional laparoscopic surgery, showing no significant difference.

| Case | Age | Gender | Tumor size (mm) | TNM stage | Operation time (min) | Suturing time (min) | Blood loss | Complication | Wexner incontinence score | |

| 3 mo 6 mo | ||||||||||

| 1 | 63 | F | 30 | T2N0 | 214 | 13 | 10 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 72 | F | 22 | T1N0 | 252 | 20 | 90 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 47 | F | 35 | T3N0 | 315 | 24 | 10 | Anal pain | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 70 | M | 38 | T3N0 | 343 | 20 | 150 | Ischemic colitis | 6 | 1 |

| 5 | 62 | M | 20 | T1N0 | 312 | 23 | 228 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 77 | M | 35 | T3N0 | 256 | 17 | 200 | - | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 65 | M | 38 | T3N1 | 260 | 13 | 35 | Leakage | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 72 | F | 15 | T1N0 | 345 | 15 | 203 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 65 | M | 26 | T2N0 | 262 | 13 | 27 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 66 | M | 23 | T2N0 | 280 | 18 | 120 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 70 | F | 20 | T1N0 | 247 | 13 | 118 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 46 | M | 18 | T1N0 | 277 | 18 | 92 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 56 | F | 22 | T1N0 | 250 | 14 | 30 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 68 | F | 18 | T1N0 | 291 | 11 | 145 | Anastomotic ulcer | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 57 | F | 33 | T2N0 | 267 | 8 | 95 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 40 | M | 15 | T1N0 | 281 | 10 | 30 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | 65 | M | 22 | T1N1 | 355 | 9 | 245 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | 77 | M | 50 | T3N0 | 277 | 15 | 150 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | 63 | M | 35 | T3N0 | 215 | 13 | 192 | - | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | 60 | M | 25 | T2N0 | 271 | 11 | 116 | - | 0 | 0 |

| Conventional LAP | Complete LAP | |

| Age | 66.3 ± 11 | 63.7 ± 9 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 38.5 ± 18 | 27 ± 9 |

| Dissected lymph node (count) | 17.5 ± 8.8 | 17.7 ± 7.7 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 120 ± 56 | 114 ± 72 |

| Operation time (min) | 240 ± 77 | 278 ± 39 |

| Count of usage of analgesic (times) | 5.89 ± 2.86 | 1.85 ± 1.8a |

| Term of pain (d) | 3.43 ± 1.41 | 1.9 ± 1.9a |

| Orally take (d) | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 4 ± 1.4 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 11.2 ± 3.2 | 11.0 ± 3 |

| Suture failure | 4 cases | 1 case |

| SSI | 8 cases | None |

The bleeding volume ranged from 10 mL to 245 mL with a mean of 114 ± 72 mL. The bleeding volume in conventional laparoscopic surgery was 120 ± 56 mL, denoting no significant difference between the new technique and conventional laparoscopic surgery. The mean operation time was 278 ± 39 min; the time required for purse-string suturing was 15 ± 4 min; the mean operation time in conventional laparoscopic surgery was 240 ± 77 min. There were no statistically significant differences between the techniques in procedure times.

The time to start oral ingestion after surgery was 4 ± 1.4 d for this surgical technique, which was not significantly different to the 4.3 ± 0.9 d for the conventional technique. Postoperative hospital stay was 11.8 ± 1.6 d for this surgical technique, which was not significantly different to the 11 ± 3.2 d for conventional laparoscopic surgery.

Regarding postoperative analgesia, in both groups, 0.75% ropivacaine was used for epidural anesthesia, and when pain occurred, 15 mg pentazocine mixed in 100 mL of physiological saline was administered intravenously after 1 h. With regard to pain after epidural anesthesia, the total postoperative usage of analgesia in this surgical technique was 1.85 ± 1.8 times, whereas it was 5.89 ± 2.86 in conventional laparoscopic surgery, showing a significant decrease (P = 0.001). The postoperative pain period was 1.9 ± 1.9 d for this surgical technique, whereas it was 3.43 ± 1.41 d in conventional laparoscopic surgery, showing a significant decrease (P = 0.004).

Postoperative complications in this surgical technique included suture failure in one patient, which was conservatively mitigated, and one patient each with ischemic enteritis in the anastomotic part and anal pain, which were observed early after the surgery and were conservatively mitigated, without occurrence of surgical site infection (SSI). In the conventional laparoscopic surgery cases, suture failure was found in four patients, and one of them underwent colostomy. SSI was observed in 8 patients. The postoperative follow-up period for this surgical technique ranged from 12 to 30 mo, with a mean of 20 mo. Patients at stage 3a and above underwent postoperative chemotherapy. Neither local recurrence nor remote metastasis was observed during the follow-up period. In conventional laparoscopic surgery, the postoperative follow-up period ranged from 13 to 32 mo, during which time anastomotic recurrence and remote metastasis were found in one patient each. This surgical technique draws the tumor from the anus; therefore, those with a low T factor were selected, and there may be no difference in terms of radical cure between these surgical techniques, although the background factors may vary with the patients.

Anal function was evaluated using the Wexner fecal incontinence scoring system. Evaluations at 3 mo after surgery were Score 6 in one patient, Score 1 in two patients, and Score 0 in the remaining seven patients. The patient with Score 6 developed postoperative ischemic change in the anastomotic part, and was improved to Score 1 about 6 mo after surgery. At 6 mo post surgery, only one patient had Score 1, and the other nine had Score 0.

All patients underwent intraoperative cytodiagnosis and culture: no floating cancer cells or bacteria were detected.

Laparoscopic surgery has become widely accepted as a minimally invasive surgery. With the occasional adoption of surgical methods such as single port surgery, natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery, or NOSE, the latter two of which do not involve making an incision in the abdomen, minimally invasive surgery is expected to be further developed in the future. For NOSE, the transvaginal technique has been described in terms of problems such as elasticity of the tissue or wound healing[1-5]. However, there are few reports on the transanal method. The reasons include a cumbersome procedure to transanally draw the lesion and to reconstruct it. Wolthuis et al[6] reported that they inserted the separation bag transanally and drew the lesion for left colon cancer. However, it is also reported that the resected specimen gets folded in the bag using this method, making the diameter of the specimen larger than that of the rectum, leading to damage to the residual rectum or the anus, which is the route by which the tumor is removed. To solve this problem, there is a report of a procedure to insert the wound retractor transanally and facilitate the extraction of the lesion[7]. The surgical technique that we have devised and reported uses a 1-0 loop thread for closure of the tumor towards the anal side, forming the supporting thread, and the tumor is drawn into the rectum, thereby allowing the tumor to be removed in the longitudinal direction against the rectal stump, leading to easy extraction. This method is contrary to the method of resecting the bowel after inversion, as reported by Hara et al[8] According to Katsuno et al[9], oral dissection is done after the tumor is extracted; thus it becomes possible to dissect directly after confirming the positional relation between the tumor and the vessels in the mesentery. After tumor resection, the anvil head is mounted in the reconstructed bowel extracorporeally, and is repositioned in the body cavity. Purse-string suturing of the dissected rectum is then performed laparoscopically, and reconstruction using SST is performed. SST was reported to have a reduced risk of suture failure compared with the double staple technique (DST) in some of the literature; however, other reports described no difference between them. Even though there is no established opinion[10,11] on this matter, it was considered advantageous for wound healing because no staple-on-staple anastomosis was involved. The distal margin was also considered advantageous because of homogeneity around the entire circumference.

This method necessitates bowel incision within the peritoneal cavity; therefore, intraoperative infections may occur. However, there is a report stating that bowel irrigation before opening the bowel can decrease the infection risk and intraoperative opening of the bowel does not lead to the risk of SSI[12,13].

To prevent local recurrence from opening the bowel, we performed rectal irrigation from the anus with 500 mL of physiological saline containing povidone-iodine and used intraoperative cytodiagnostic procedures to confirm that there were no cancer cells in the irrigation outflow from the residual rectum.

We also covered the resected bowel with a nylon bag to reduce the risk further. In fact, in patients that we have treated, pathogenic bacteria were not detected from the intraoperative irrigation fluid. With regard to intraoperative floating cancer cells, McKenzie et al[2] reported that transvaginal NOSE does not pose a risk for tumor implantation, and Ooi et al[14] stated that the protective barrier and specimen bag can reduce the risk of tumor implantation or local recurrence. We also performed extraction by covering the tumor with a nylon bag to completely prevent the risk of local recurrence, and the intraoperative cytodiagnostic procedures performed in all the patients indicated that no cancer cells were observed. Operation time, bleeding volume, postoperative wound pain, postoperative hospital stay, the number of totally dissected lymph nodes, and postoperative complications were compared between this method and conventional laparoscopic surgery. There were no significant differences in bleeding volume, postoperative hospital stay, the number of totally dissected lymph nodes, and suture failure between both groups, indicating similar results to conventional laparoscopic surgery. On the other hand, in conventional laparoscopic surgery, the mean operation time was 38 min shorter, although this was not a statistically significant difference. This may reflect the time required for purse-string suturing of the rectal stump and the time to adequately manipulate the descending colon. However, the mean operating time gradually decreased with the increase in the number of treated cases, suggesting the existence of a learning curve. The postoperative complications of this surgical technique included ischemic enteritis of the anastomosis part and postoperative anal pain in one patient each, which were conservatively mitigated. SSI was observed in eight patients in conventional laparoscopic surgery, whereas there were no occurrences in this surgical technique. Although no significant difference was observed in the incidence of SSI, it may become evident in the future with the accumulation of cases.

The indications for this method may require several conditions, as described below, to perform the extraction transanally.

Indications for transanal extraction include: the location of the primary lesion is at the distal side of the sigmoid colon to the upper side of the rectum; the tumor diameter is less than 5 cm; there is no serosal exposure, as evaluated by CT; there is little metastasis of the lymph nodes; and there is no bulky mesorectum, as evaluated by a body mass index less than 30 kg/m2. Those with a massive tumor or surrounding lymph nodes depicted on CT were excluded because of the difficulty of transanal extraction. Sufficient exfoliation and manipulation up to the splenic flexure are necessary to remove the tumor and to reconstruct the bowel transanally out of the body. If the sigmoid colon has sufficient length, the surgery becomes much easier. If these conditions are not fulfilled, insufficient resection of the proximal margin or damage to the mesentery of the reconstructed bowl from excessive traction of the resected bowel may occur. If the resection line towards the anal side is ≥ 2 cm lower than the peritoneal reflection, laparoscopic purse-string suturing may be technically difficult; in such cases, sufficient exfoliation of the rectum towards the anal side is necessary.

For these reasons, the difficulty level and the pros and cons of the surgery tend to be dependent on the location of the tumor and the degree of progression. The best indication is for a patient with a tumor of less volume, located in the vicinity of the rectosigmoid segment, and length of the sigmoid colon has sufficient margins.

Despite the existence of the above conditions, this method, compared with the conventional method, had a significantly lower frequency of postoperative analgesic usage and shorter postoperative pain period because it does not involve the creation of an incision. Even though no significant difference could be established because of the small number of patients and no complications of SSI were observed, it can be inferred that there may be a sufficient advantage in not making any incision. With regard to the number of totally dissected lymph nodes or postoperative recurrence, no significant differences were observed, and with regard to radical curation and safety, this method was equivalent to the conventional method in these 20 patients. Therefore, we concluded that this method can be accepted as a minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancer or sigmoid colon cancer.

In conclusion, we have performed complete laparoscopic anterior resection using the NOSE method in 20 patients with rectal cancer. This method does not require any incision in the abdomen, and has excellent cosmetic properties with mitigated postoperative pain. Therefore, we this technique should be accepted as a novel minimally invasive surgery. This surgical technique may require several conditions, and it will be necessary to establish this technique and indications based on further examination and accumulation of more cases.

Recently, laparoscopic anterior resection for rectal cancer has become a common practice. However, a small incision is still made in the abdomen to resect the tumor. This small incision causes postoperative wound pain, and has risks of infections, adhesions after surgery, or incisional herniation.

At present, natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) has been reported as a less invasive surgery to solve complications caused by creating incisions.

The present study showed that complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE is the same as conventional laparoscopic anterior resection in terms of safety and oncological outcome, does not require any incision in the abdomen, and has excellent cosmetic properties.

NOSE for colorectal cancer can avoid making any incision to extract the specimen. The method of extracting the specimen is the most important process in NOSE surgery. We describe an easy way to extract the specimen without causing residual rectal injury. This should allow NOSE surgery to be applied in treating various diseases.

NOSE for colorectal cancer can avoid making incisions to extract the specimen. Complete laparoscopic anterior resection with NOSE is the same as conventional laparoscopic anterior resection in terms of surgical outcomes, and had a significantly lower frequency of postoperative analgesic usage and shorter postoperative pain period, as it does not involve making any incision.

This study reported the detailed surgical procedures and benefits of laparoscopic rectal surgery with the NOSE technique. This method, as an advanced minimally invasive surgery, seems to be quite attractive and may hold a high position among previously reported NOSE techniques.

P- Reviewer: Fierbinteanu-Braticevici C, Ker CG, Matsuda A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Jategaonkar PA, Anand NV. An innovative technique for colorectal specimen retrieval: a new era of “natural orifice specimen extraction” (N.O.S.E). Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1120-1124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McKenzie S, Baek JH, Wakabayashi M, Garcia-Aguilar J, Pigazzi A. Totally laparoscopic right colectomy with transvaginal specimen extraction: the authors’ initial institutional experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2048-2052. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choi GS, Park IJ, Kang BM, Lim KH, Jun SH. A novel approach of robotic-assisted anterior resection with transanal or transvaginal retrieval of the specimen for colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2831-2835. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Han FH, Hua LX, Zhao Z, Wu JH, Zhan WH. Transanal natural orifice specimen extraction for laparoscopic anterior resection in rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7751-7757. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang Q, Wang C, Sun DH, Kharbuja P, Cao XY. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision with natural orifice specimen extraction. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:750-754. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wolthuis AM, Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D’Hooghe T, Fieuws S, Penninckx F, D’Hoore A. Laparoscopic sigmoid resection with transrectal specimen extraction: a novel technique for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1348-1355. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nishimura A, Kawahara M, Suda K, Makino S, Kawachi Y, Nikkuni K. Totally laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy with transanal specimen extraction. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3459-3463. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hara M, Takayama S, Sato M, Imafuji H, Takahashi H, Takeyama H. Laparoscopic anterior resection for colorectal cancer without minilaparotomy using transanal bowel reversing retrieval. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:e235-e238. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katsuno G, Fukunaga M, Nagakari K, Yoshikawa S, Ouchi M, Hirasaki Y, Azuma D. Natural orifice specimen extraction using prolapsing technique in single-incision laparoscopic colorectal resections for colorectal cancers. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2014;7:85-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim HJ, Choi GS, Park JS, Park SY. Comparison of intracorporeal single-stapled and double-stapled anastomosis in laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a case-control study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:149-156. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Marecik SJ, Chaudhry V, Pearl R, Park JJ, Prasad LM. Single-stapled double-pursestring anastomosis after anterior resection of the rectum. Am J Surg. 2007;193:395-399. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bucher P, Wutrich P, Pugin F, Gonzales M, Gervaz P, Morel P. Totally intracorporeal laparoscopic colorectal anastomosis using circular stapler. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1278-1282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maeda K, Maruta M, Hanai T, Sato H, Horibe Y. Irrigation volume determines the efficacy of “rectal washout”. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1706-1710. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ooi BS, Quah HM, Fu CW, Eu KW. Laparoscopic high anterior resection with natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) for early rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:61-64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |