Published online Mar 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2352

Revised: January 3, 2014

Accepted: January 14, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2014

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most devastating solid tumors, and it remains one of the most difficult to treat. The treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) is systemic, based on chemotherapy or best supportive care, depending on the performance status of the patient. Two chemotherapeutical regimens have produced substantial benefits in the treatment of MPC: gemcitabine in 1997; and FOLFIRIONOX in 2011. FOLFIRINOX improved the natural history of MPC, with overall survival (OS) of 11.1 mo. Nab-paclitaxel associated with gemcitabine is a newly approved regimen for MPC, with a median OS of 8.6 mo. Despite multiple trials, this targeted therapy was not efficient in the treatment of MPC. Many new molecules targeting the proliferation and survival pathways, immune response, oncofetal signaling and the epigenetic changes are currently undergoing phase I and II trials for the treatment of MPC, with many promising results.

Core tip: This paper will be the newest study with the most recent updates in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. After a brief review of the different treatments for metastatic pancreatic cancer, the current treatment options are discussed, as well as novel therapies and approaches in the future.

- Citation: Ghosn M, Kourie HR, Karak FE, Hanna C, Antoun J, Nasr D. Optimum chemotherapy in the management of metastatic pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(9): 2352-2357

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i9/2352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2352

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the most aggressive and devastating solid tumors with the worst mortality. The median overall survival (OS) is less than 6 mo, and less than five percent of patients will survive more than 5 years (2% in cases of metastatic pancreatic cancer). The large majority of pancreatic cancers are locally advanced (50%) or metastatic (40%) because of their late diagnoses[1].

PC remains one of the most difficult cancers to treat due to its intrinsic resistance to conventional treatments. Many regimens have been implicated in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancers (MPC), but only two have had significant impact: GEMCITABINE, introduced in 1997[2]; and FOLFIRINOX, introduced in 2011[3]. In the era of targeted therapy, the treatment of pancreatic cancer remains based mainly on chemotherapeutical regimens.

The primary goals of treatment in MPC are better quality of life, palliation and improved survival. The vast majority of chemotherapeutic drugs have been tried in the treatment of MPC, but few have been selected as standards of care.

Before the approval of GEMCITABINE, 5-FU was the most evaluated agent for MPC, without any survival amelioration. In 1997, Gemcitabine was approved by the FDA, based on the results of a randomized trial, in which Gemcitabine was compared to 5-FU in previously untreated patients. A total of 23.8% of Gemcitabine-treated patients experienced a clinical response, compared with 4.8% of 5-FU-treated patients (P = 0.0022), while the median survival was only extended by 1.24 mo (5.65 vs 4.41) in favor of patients receiving Gemcitabine (P = 0.025). The one-year survival rate was 18% for Gemcitabine patients and 2% for 5-FU patients[2].

Since the Gemcitabine era, many gemcitabine-based combination therapies have been widely evaluated over the past decade. Most trials have used a second cytotoxic agent, such as 5-FU[4], capecitabine[5], oxaliplatin[6], cisplatin[7], irinotecan[8] and pemetrexed[9], or a targeted therapy, such as cetuximab[10], bevacizumab[11], erlotinib[12] and aflibercept[13], administered in combination with gemcitabine (Table 1). However, despite a modest improvement in progression-free survival in some trials, a significant benefit in overall survival could not be demonstrated for the majority of these combination therapies.

Of all of these treatments, eroltinib, which positively impacted overall survival, was approved for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer[10]; the addition of bevacizumab to gemcitabine-erlotinib did not lead to a statistically significant improvement in OS[14]. A trend toward better survival was also observed with a gemcitabine-capecitabine regimen. Finally, two meta-analyses, the first by Heinemann et al[15] and the second by Sultana et al[16], concluded that there was a significant survival benefit when gemcitabine was associated with another agent (platinum and 5-FU derivatives) in patients with good performance status. A recent retrospective study by Khalil et al[17] in 2013 reported that adding erlotinib to gemcitabine-cisplatin did not appear to improve OS in MPC.

In 2007, we reported on a phase II clinical trial assessing a gemcitabine-free regimen based on FOLFOX 6, with promising results. A partial response was observed in 27.5% of the patients and stable disease in 34.5%[18]. Our study and the study by Louvet et al[6], which associated gemcitabine and oxaliplatine (RR of 26.8%, the highest with any gemcitabine-based regimen), highlighted the potential role of oxaliplatine in the treatment of MPC.

A second revolution marked the history of MPC in 2011, when Conroy et al[3] reported for the first time in NEJM a significant improvement in OS using a gemcitabine–free regimen-the FOLFIRIONOX regimen, based on three chemotherapeutic drugs: 5-FU, irinotecan and oxaliplatine. In this study, the median OS of the patients receiving FOLFIRINOX was 11.1 mo compared to 6.8 mo in the group of patients receiving gemcitabine alone, with an objective response rate of 31.6% compared to 9.4% in favor of the FOLFIRINOX arm. However, more adverse events, such as febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, sensory neuropathy and diarrhea, were noted in the group of patients receiving FOLFIRINOX. This regimen was considered an option for the treatment of patients with MPC and good performance status[3]. A recent study demonstrated that FOLFIRINOX significantly reduced quality of life impairment compared with gemcitabine in patients with MPC[19].

Since the results with the FOLFIRINOX gemcitabine-free regimen, a new attempt with gemcitabine-based combination therapy revealed promising results. Another agent added to gemcitabine was the nab-paclitaxel, an albumin-bound nanoparticle form of paclitaxel that increases the tumor accumulation of paclitaxel through binding of albumin to SPARC. A randomized phase III study that compared a combination of nab-paclitaxel and Gemcitabine weekly to gemcitabine alone showed a significant improvement in overall survival of 8.5 mo vs 6.7 mo (P < 0.05) and a response rate of 23% vs 7%[20]. An important prognostic biomarker in patients with MPC receiving nab-paclitaxel is SPARC; a positive SPARC status in these patients was associated with a significant increase in OS[21].

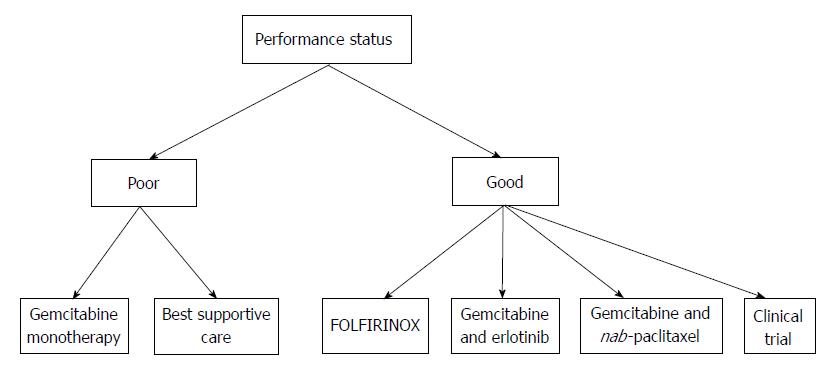

Treatment is systemic, based on chemotherapy or best supportive care, depending on the performance status of the patient.

In patients with limited performance status, Gemcitabine as monotherapy is the uniquely approved treatment; another alternative is best supportive care. In patients with good performance status, many chemotherapeutical regimens are available (Table 2). Gemcitabine is still considered a possible option[1]. FOLFIRINOX offers the best overall survival and response rate in MPC, but it causes many side effects. Gemcitabine associated with nab-paclitaxel offers the second best overall survival, with fewer side effects compared to FOLFIRINOX[16,18]. A comparison between the side effects of these three regimens is resumed in the Table 3. Erlotinib remains the unique targeted therapy approved for the treatment of MPC in combination with gemcitabine. Gemcitabine combined with cisplatin or capecitabine can be a reasonable choice in some cases. Patients with MPC and good performance status can also be included in different phase I or II clinical trials. All of the approved treatments for MPC in patients having poor and good performance status are reviewed in Figure 1.

| Adverse events | Gemcitabine | FOLFIRINOX | Gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel |

| Neutropenia | 21% | 45.7% | 38% |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1.2% | 5.4% | 3% |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3.6% | 9.1% | 13% |

| Fatigue | 17.8% | 23.6% | 17% |

| Diarrhea | 1.8% | 12.7% | 6% |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 0% | 9.0% | 17% |

The second-line treatment for MPC has been evaluated in only a few trials. The general guidelines for treatment are to use fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy if the patient was previously treated with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy and gemcitabine-based chemotherapy if previously treated with fluoropyrimidine-based therapy[22]. A phase II trial investigated whether the association of capecitabine with oxaliplatin was active in gemcitabine-pretreated patients with MPC, especially patients with a good performance status and those who responded to first-line chemotherapy[23]. A phase III trial comparing the OFF regimen (oxaliplatin; 5-FU; folinic acid) to best supportive care provided first-time evidence for the benefit of second-line chemotherapy in MPC, manifested by prolonged survival time[24]. Palliative radiotherapy has been proposed as salvage therapy for patients with severe pain refractory to narcotics[22].

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been considered, for the last decade, the two main targets that should be studied in MPC. Many trials have combined gemcitabine with an anti-angiogenic drug or a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (Table 1); all of these trials have had negative results, except for the combination of gemcitabine and erlotinib, as mentioned above.

After multiple failures with targeted therapy for MPC based on anti-EGFR and anti-VEGF, many new concepts for treating MPC are being elaborated, including the targeting of tyrosine kinase signaling, cascade elements, the stromal reaction, the immune response, oncofetal signaling and epigenetic changes[25].

IFG1R, MEK, PI3K, AKT, and mTOR are actually the most frequent signaling pathway targets evaluated in the treatment of MPC. A phase II trial reported that ganitumab (AMG 479), an mAb antagonist of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, combined with gemcitabine showed a trend toward improved 6-mo survival and overall survival rates[26]. Many other trials had negative results: selumetinib (AZD6244), a selective MEK inhibitor compared to capecitabine as a second-line treatment after gemcitabine, did not demonstrate any statistically significant difference in overall survival[27]; an oral m-TOR inhibitor (RAD001) had minimal clinical activity in gemcitabine-resistant MPC[28].

Immunotherapy is one of the promising new concepts introduced in the treatment of MPC. A phase I study of an agonist of CD40 monoclonal antibody (CP-870, 893), in combination with gemcitabine, was well tolerated in patients with MPC and was associated with anti-tumor activity[29]. Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), another immunotherapeutic option approved for metastatic melanoma[30], was considered ineffective in the treatment of MPC after the results of a phase II trial; association of these agents with other agents could probably have more promising results[31].

Another approach in the treatment of MPC is the targeting of oncofetal signaling, which is responsible for tumor progression and resistance to chemotherapy in PC. One of the most altered pathways incriminated in the development of PC is the Notch pathway[32]; the activation of γ-secretase is the primum movens of activation of Notch signaling. Preclinical data suggested that a selective γ-secretase inhibitor (PF-03084014) had greater anti-tumor activity in combination with gemcitabine in PC, providing a rationale for further investigation of this combination in PC[33]. Many other trials are evaluating agents targeting the stromal reaction and epigenetic changes[34,35].

Another targeted therapy, AGS-1C4D4, a fully human monoclonal antibody against prostate stem cell antigen, was evaluated with gemcitabine in a randomized phase II study of untreated MPC, with achievement of its primary end point in demonstrating improved 6-mo SR[36]. All of the recent phase II trials studying the new agents in the treatment of MPC are summarized in Table 4.

| Reference | New agents | Agents target | Phase of the study and targeted population | Arms of the study | Conclusion of the study |

| Kindler et al[26] | Ganitumab (AMG479) | mAb antagonist of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | Phase II; untreated MPC patients | Gem/ganitumab vs gem | Improved 6-mo survival rate and OS |

| Bodoky et al[27] | Selumetinib (AZD6244) | Selective MEK inhibitor | Phase II; second line treatment after gemcitabine | Selutimumab vs capecitabine | No significant difference in OS |

| Wolpin et al[28] | Everolimus (RAD001) | m-TOR inhibitor | Phase II; second line treatment after gemcitabine | Everolimus (single arm study) | Minimal clinical activity |

| Royal et al[31] | Ipilimumab (MDX010) | Anti-CTLA4 | Phase II; untreated MPC patients | Ipilimumab (single arm study) | Ineffective in the treatment of MPC |

| Wolpin et al[36] | AGS-1C4D4 | mAb to prostate stem cell Antigen | Phase II; untreated MPC patients | Gemcitabine/AGS-1C4D4 vs gemcitabine | Improved 6-mo survival rate |

Many new targets and genes that play roles in the pathogenesis and progression of PC are being evaluated in animals or in cancer cells for their potential diagnostic and therapeutic implications: mucin (myc) was studied by Rachagani et al[37], transketolase by Wang et al[38] and aberrant CD20 expression by Chang et al[39].

The combination of these novel therapies and approaches could positively affect the history of MPC.

Despite multiple trials and their major efforts, PC remains resistant to chemotherapy and targeted therapy. It seems that the results obtained with chemotherapy, targeted therapy and their combination in MPC have reached a plateau, with significant, but modest, amelioration of OS of less than one year. Stratified or personalized therapy is totally absent in the treatment of MPC, due to the absence of prognostic or therapeutic markers and the lack of molecular profiling modalities. Many trials are currently being conducted to explore new targets in the tumorigenesis and proliferation of PC. Finally, the combination of these novel therapies with personalized medicine might offer promising results in patients with MPC.

P- Reviewers: Liu DL, Marin JJG S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25182] [Article Influence: 1937.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403-2413. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817-1825. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4838] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5100] [Article Influence: 392.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Berlin JD, Catalano P, Thomas JP, Kugler JW, Haller DG, Benson AB. Phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3270-3275. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W, Gerber D, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schüller J, Saletti P. Clinical benefit and quality of life in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer receiving gemcitabine plus capecitabine versus gemcitabine alone: a randomized multicenter phase III clinical trial--SAKK 44/00-CECOG/PAN.1.3.001. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3695-3701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, Lledo G, Zampino MG, André T, Zaniboni A, Ducreux M, Aitini E, Taïeb J. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3509-3516. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Colucci G, Labianca R, Di Costanzo F, Gebbia V, Cartenì G, Massidda B, Dapretto E, Manzione L, Piazza E, Sannicolò M. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with single-agent gemcitabine as first-line treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: the GIP-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1645-1651. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 224] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rocha Lima CM, Green MR, Rotche R, Miller WH, Jeffrey GM, Cisar LA, Morganti A, Orlando N, Gruia G, Miller LL. Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3776-3783. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Oettle H, Richards D, Ramanathan RK, van Laethem JL, Peeters M, Fuchs M, Zimmermann A, John W, Von Hoff D, Arning M. A phase III trial of pemetrexed plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine in patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1639-1645. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Philip PA, Benedetti J, Corless CL, Wong R, O’Reilly EM, Flynn PJ, Rowland KM, Atkins JN, Mirtsching BC, Rivkin SE. Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus cetuximab versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial S0205. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3605-3610. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 478] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Sutherland S, Schrag D, Hurwitz H, Innocenti F, Mulcahy MF, O’Reilly E, Wozniak TF. Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 80303). J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3617-3622. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 645] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Murawa P, Walde D, Wolff RA. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960-1966. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Rougier P, Riess H, Manges R, Karasek P, Humblet Y, Barone C, Santoro A, Assadourian S, Hatteville L, Philip PA. Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group phase III study evaluating aflibercept in patients receiving first-line treatment with gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2633-2642. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 142] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Van Cutsem E, Vervenne WL, Bennouna J, Humblet Y, Gill S, Van Laethem JL, Verslype C, Scheithauer W, Shang A, Cosaert J. Phase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2231-2237. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 478] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Heinemann V, Labianca R, Hinke A, Louvet C. Increased survival using platinum analog combined with gemcitabine as compared to single-agent gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: pooled analysis of two randomized trials, the GERCOR/GISCAD intergroup study and a German multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1652-1659. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Sultana A, Smith CT, Cunningham D, Starling N, Neoptolemos JP, Ghaneh P. Meta-analyses of chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2607-2615. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Khalil MA, Qiao W, Carlson P, George B, Javle M, Overman M, Varadhachary G, Wolff RA, Abbruzzese JL, Fogelman DR. The addition of erlotinib to gemcitabine and cisplatin does not appear to improve median survival in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2013;31:1375-1383. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ghosn M, Farhat F, Kattan J, Younes F, Moukadem W, Nasr F, Chahine G. FOLFOX-6 combination as the first-line treatment of locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:15-20. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Gourgou-Bourgade S, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Boige V. Impact of FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:23-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 328] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Daniel D. Randomized phase III study of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (MPACT). USA: ASCO 2013; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, Laheru DA, Smith LS, Wood TE, Korn RL, Desai N, Trieu V, Iglesias JL. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548-4554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 755] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 835] [Article Influence: 64.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma 2013. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Xiong HQ, Varadhachary GR, Blais JC, Hess KR, Abbruzzese JL, Wolff RA. Phase 2 trial of oxaliplatin plus capecitabine (XELOX) as second-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2046-2052. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pelzer U, Schwaner I, Stieler J, Adler M, Seraphin J, Dörken B, Riess H, Oettle H. Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (OFF) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1676-1681. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 237] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Michl P, Gress TM. Current concepts and novel targets in advanced pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:317-326. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kindler HL, Richards DA, Garbo LE, Garon EB, Stephenson JJ, Rocha-Lima CM, Safran H, Chan D, Kocs DM, Galimi F. A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 study of ganitumab (AMG 479) or conatumumab (AMG 655) in combination with gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2834-2842. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 142] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bodoky G, Timcheva C, Spigel DR, La Stella PJ, Ciuleanu TE, Pover G, Tebbutt NC. A phase II open-label randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of selumetinib (AZD6244 [ARRY-142886]) versus capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who have failed first-line gemcitabine therapy. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1216-1223. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wolpin BM, Hezel AF, Abrams T, Blaszkowsky LS, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA, Enzinger PC, Allen B, Clark JW, Ryan DP. Oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:193-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 241] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Beatty GL, Torigian DA, Chiorean EG, Saboury B, Brothers A, Alavi A, Troxel AB, Sun W, Teitelbaum UR, Vonderheide RH. A phase I study of an agonist CD40 monoclonal antibody (CP-870,893) in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6286-6295. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 334] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711-723. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10799] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11106] [Article Influence: 793.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, Mathur A, Hughes M, Kammula US, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Yang JC, Lowy I, Rosenberg SA. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33:828-833. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 701] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 859] [Article Influence: 66.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Heiser PW, Hebrok M. Development and cancer: lessons learned in the pancreas. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:270-272. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Yabuuchi S, Pai SG, Campbell NR, de Wilde RF, De Oliveira E, Korangath P, Streppel MM, Rasheed ZA, Hidalgo M, Maitra A. Notch signaling pathway targeted therapy suppresses tumor progression and metastatic spread in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;335:41-51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chan E, Arlinghaus LR, Cardin DB, Goff LW, Yankeelov TE, Berlin J, McClanahan P, Holloway M, Parikh AA, Abramson RG. Phase I trial of chemoradiation with capecitabine and vorinostat in pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:225. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Oettle H, Seufferlein T. Phase I/II study with trabedersen (AP 12009) monotherapy for the treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, malignant melanoma, and colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:abstract 2513. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Wolpin BM, O’Reilly EM, Ko YJ, Blaszkowsky LS, Rarick M, Rocha-Lima CM, Ritch P, Chan E, Spratlin J, Macarulla T. Global, multicenter, randomized, phase II trial of gemcitabine and gemcitabine plus AGS-1C4D4 in patients with previously untreated, metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1792-1801. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Rachagani S, Torres MP, Kumar S, Haridas D, Baine M, Macha MA, Kaur S, Ponnusamy MP, Dey P, Seshacharyulu P. Mucin (Muc) expression during pancreatic cancer progression in spontaneous mouse model: potential implications for diagnosis and therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:68. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Wang J, Zhang X, Ma D, Lee WN, Xiao J, Zhao Y, Go V, Wang Q, Yen Y, Recker R. Inhibition of transketolase by oxythiamine altered dynamics of protein signals in pancreatic cancer cells. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2:18. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Chang DZ, Ma Y, Ji B, Liu Y, Hwu P, Abbruzzese JL, Logsdon C, Wang H. Increased CDC20 expression is associated with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma differentiation and progression. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |