Published online Mar 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i12.3432

Peer-review started: August 10, 2015

First decision: September 9, 2015

Revised: October 14, 2015

Accepted: November 24, 2015

Article in press: November 24, 2015

Published online: March 28, 2016

AIM: To assess the efficacy and safety of intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy in patients undergoing laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) for gastric cancer.

METHODS: A retrospective review of 81 consecutive patients who underwent LTG with the same surgical team between November 2007 and July 2014 was performed. Four types of intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy using staplers or hand-sewn suturing were performed after LTG. Data on clinicopatholgoical characteristics, occurrence of complications, postoperative recovery, anastomotic time, and operation time among the surgical groups were obtained through medical records.

RESULTS: The average operation time was 288.7 min, the average anastomotic time was 54.3 min, and the average estimated blood loss was 82.7 mL. There were no cases of conversion to open surgery. The first flatus was observed around 3.7 d, while the liquid diet was started, on average, from 4.9 d. The average postoperative hospital stay was 10.1 d. Postoperative complications occurred in 14 patients, nearly 17.3%. However, there were no cases of postoperative death.

CONCLUSION: LTG performed with intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy using laparoscopic staplers or hand-sewn suturing is feasible and safe. The surgical results were acceptable from the perspective of minimal invasiveness.

Core tip: Totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy using intracorporeal anastomosis has gradually increased with advances in laparoscopic surgical instrumentation. However, intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy is still uncommon after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy due to technical difficulties. Herein, we evaluate various types of intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy using laparoscopic staplers and a hand-sewn technique.

- Citation: Chen K, Pan Y, Cai JQ, Xu XW, Wu D, Yan JF, Chen RG, He Y, Mou YP. Intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy: A single-center 7-year experience. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(12): 3432-3440

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i12/3432.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i12.3432

Since the first reported laparoscopy assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) was performed for gastric disease in 1994[1], for tumors relatively low in the stomach, interest for this surgical approach has continued to grow. For middle or upper gastric adenocarcinoma, laparoscopy assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) has become more popular than laparoscopy assisted proximal gastrectomy (LAPG) due to the relatively lower rate of reflux esophagitis. In addition, LATG is the treatment of choice for middle or upper gastric adenocarcinoma with deeper invasion[2,3].

Because of the narrow operating window, however, technical problems during extracorporeal esophagojejunostomy may necessitate performing an exit via a mini-laparotomy. This relatively small incision has a number of disadvantages, including removal of the possibly challenging specimen, contamination through the incision, and extra pulling over the residual stomach[4].

Based on our extensive laparoscopic experience obtained from performing laparoscopic pancreatic, gastric, and other operations[5-11], we developed totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) for middle or upper gastric cancer. Here, we describe our 7-year experience using this technique and the short-term clinical results obtained using different kinds of intracorporeal esphagojejunostomy using laparoscopic staplers or a hand-sewn suture technique.

From November 2007 to July 2014, a total of 81 consecutive patients with gastric cancer underwent TLTG that was performed by a single surgical team at Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital. Preoperative clinical evaluation, which included clinical grading, was assessed with computed tomography, abdominal ultrasonography, endoscopic ultrasonography, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and gastrointestinal radiography.

Clinical statistics were collected from medical records of the patients: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), method of anastomosis, time required for anastomosis, total operation time, estimated blood loss, the day of first flatus and liquid diet, postoperative complications, and length of the postoperative hospital stay. Pathological and clinical staging was determined based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (the 7th edition) and the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification scheme. This research was approved by the Zhejiang University’s Ethics Committee. Written consent was obtained from every patient prior to enrollment in the study.

A former depicted approach was used to position the patient and the trocar location[6]. Five major trocars were inserted in the V-shape arrangement. The guidelines of gastric cancer in Japan served as the principle, including the No. 8a, 9, 10, 11p, 11d, and 12a apart from the dissection of D1. The operation was started by retracting the greater omentum and then bluntly dissembling along with the transverse colon, which is the border that accesses the lesser sac. In addition, the gastroepiploic vessels were confirmed, clipped, and then excised. Mobilization was begun at the comparative superior edge of the pancreas, thereby unveiling the celiac trunk. The common hepatic artery, the right gastric artery, and the left gastric artery together with the splenic artery and the neighboring lymph nodes were excised and identified. Meanwhile, those veins were excised and clipped. The hepatogastric and hepatoduodenal ligaments were dissected. The duodenum was later transected with 3 cm from the pylorus using the endoscopic linear stapler. The jejunum was then stapled using an endoscopic linear stapler, which was 20 cm from Treitz’s ligament. The detailed lymphadenectomy was described in our previously published study[7]. In general, there were two approaches for intracorporeal gastrointestinal reconstruction, mechanical circular or linear staplers and the hand-sewn suture technique. However, in our experience, we found some limitations using these mechanical approaches. Therefore, we have used intracorporeal hand-sewn gastrointestinal anastomosis since September 2012.

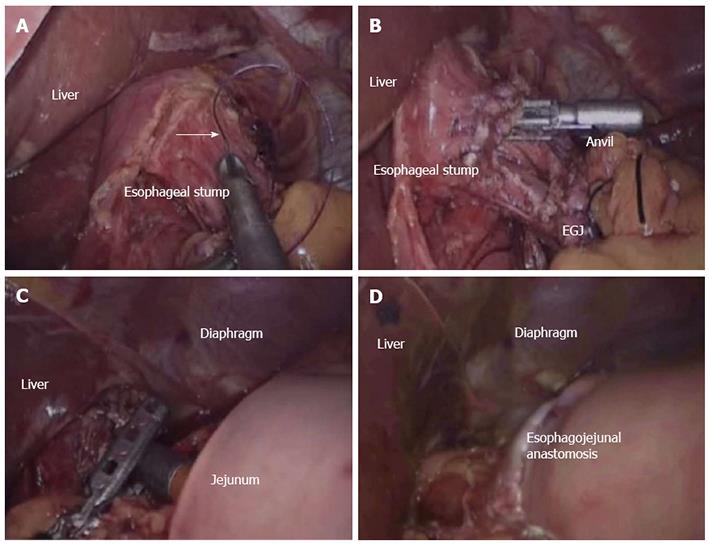

Conventional circular stapler-anvil method (Type A): This technique is an anvil method. The stomach was lifted up and then a purse-string construction was placed 1 cm above the line that was predetermined transected (Figure 1A). A hole was made with the esophagogastric junction using a harmonic scalpel. The anvil was introduced to the esophageal stump via the hole of purse-string construction, and the hole was tied (Figure 1B). The esophagogastric junction was later divided, and the stomach was also extracted. The circular stapler was utilized in the jejunum via the jejuna stump and was later attached with the anvil (Figure 1C). The esophagojejunostomy was finished by firing the circular stapler (Figure 1D). The jejunum stump was closed using the endoscopic linear stapler.

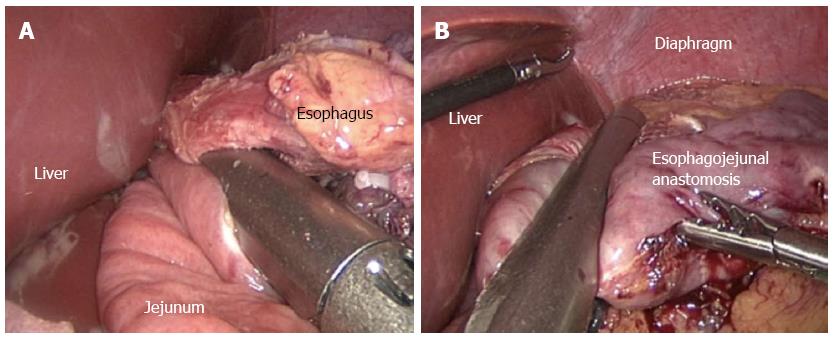

Linear stapler side-to-side method (Type B): A relative small opening was made into the 10 cm ranking from the stump over the distal jejunum, and the latter was then pulled up to the esophagus, in which a small side opening was also made. A antiperistalic side-to-side esophagojejunostomy was later presented with a linear stapler (Figure 2A). The esophagus and the residual hole were closed using the stapler (Figure 2B).

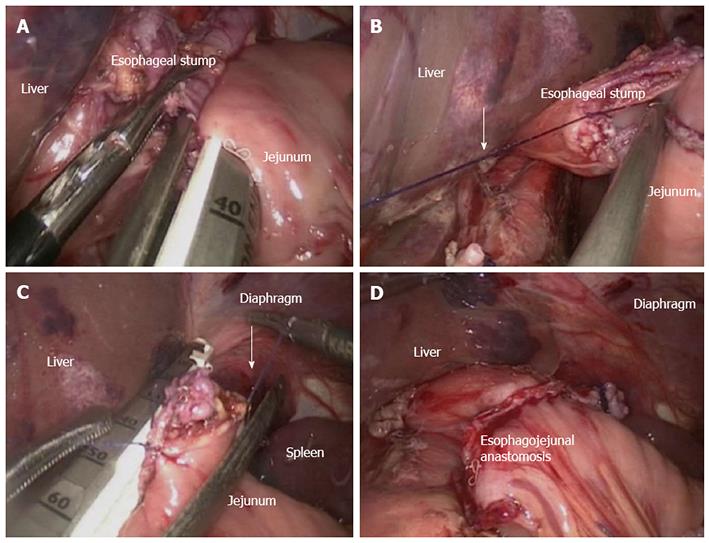

Linear stapler delta-shaped method (Type C): The escophageogastric junction was transected through the endoscopic linear stapler. Small holes were then created alongside the edge of the jejunum and the esophageal stump. The posterior walls of both the esophageal stump and the jejunum were approximated and joined by the endoscopic linear stapler (Figure 3A). The staple line was inspected later for hemostasis and defects. Stay sutures were placed to lift the common opening (Figure 3B); which was then closed with two applications of the linear stapler (Figure 3C), leading to the reconstruction over the intracorporeal tract (Figure 3D).

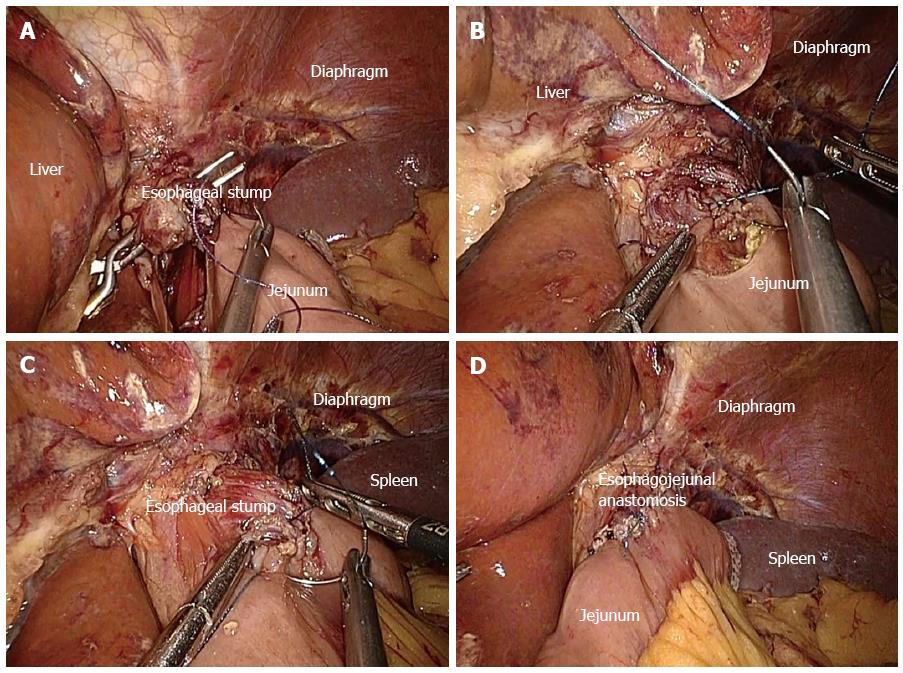

Hand-sewn end-to-side method (Type D): The jejunal loop was brought up to reach the esophageal stump. The jejunum was anchored to the esophageal stump through several serosal muscularis interrupted sutures that were placed in the posterior layer of the esophageal stump (Figure 4A). Two small holes were created: one on the esophageal stump and the other over the anti-mesenteric aspect of the jejunum. The posterior wall was latterly closed through a number of full-thickness sutures (Figure 4B). In addition, the closure over the anterior wall was carried out via the full-thickness sustainable suture (Figure 4C). Lastly, the seromuscular layer was finally strengthened through interrupted sutures to decrease the tension (Figure 4D).

After the strengthening over the seromuscular layer, which was facilitated with interrupted sutures to decrease tension, the esophageal wall was sutured to those of the diaphragm to minimize tension. The specimen was placed over the retrieval bag and latterly removed via an enlarged umbilical incision. The pneumoperitoneum was latterly established again. The routine of the Roux-en-Y anatomosis was presented laparoscopically among the distal jejunum (40 cm from the esophagojejunostomy) and then the proximal jejunum. Any specific defect over the mesentery was closed.

After surgery, all patients were cared for in the general ward. The nasogastric tube was removed at the end of surgery in the operating room. Patients were supported through the TPN before they finally took a liquid diet. If the patients could tolerate the liquid diet, they were offered a semiliquid diet. The anastomosis was checked on postoperative days 3-7 via conducting an upper gastrointestinal radiography facilitated with Gastrografin as the opposite medium. Patients were discharged from the hospital if they resumed a semi-liquid diet and their average blood temperature and work panel was without obvious abnormalities. The anastomoses were assessed again within 3 mo by gastroscopy.

Patients were followed up every 3 mo during the next 2 years after surgery and every 6 mo during the 3 years after that. Routine follow-up covered the physical test, laboratory examination, endoscopy, computed tomography or ultrasonography, and chest radiography. Every patient was observed until death or the last follow-up date of May 2015.

Table 1 illustrates the clinical features and pathological characteristics held by the patients. The average age of the patients was 59.0 years, and the ratio of females to male was 2:1. The average BMI was 22.2 kg/m2. Well over one-third of the patients suffered from comorbidities, with the most common being hypertension. The average neoplasm size was 4.0 cm. Approximately half of the patients had lesions that were staged as T1 (39.5%), N0 (49.4%), and stage I (43.2%) neoplasms. Sixty percent of patients suffered from advanced gastric cancer, which was defined as tumor invasion into the layer of the proper muscular.

| Variable | Value (%) |

| Gender (male/female) | 54 (66.6)/27 (33.3) |

| Age (yr) | 59.0 ± 10.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.2 ± 3.1 |

| ASA classification (I/II/III) | 43 (53.1)/36 (44.4)/2 (2.5) |

| Comorbidities1 | 31 (38.3) |

| Hypertension | 20 (24.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (7.4) |

| Cardiovascular | 7 (8.6) |

| Pulmonary | 6 (7.4) |

| Liver | 2 (2.5) |

| Others | 2 (2.5) |

| Tumor size (cm) | 4.0 ± 2.4 |

| Histology (differentiated/undifferentiated) | 42 (51.9)/39 (48.1) |

| T stage (T1/T2/T3/T4) | 32 (39.5)/10 (12.3)/11 (13.6)/28 (34.6) |

| N stage (N0/N1/N2/N3) | 40 (49.4)/11 (13.6)/13 (16.0)/17 (21.0) |

| TNM stage (I/II/III/IV) | 35 (43.2)/17 (21.0)/29 (35.8)/0 (0.0) |

The operative results together with the following postoperative clinical process statistics are presented in Table 2. The anastomotic approaches adopted served as type A among 18 patients, type B among 22 patients, type C among 10 patients, and type D among 31 patients. The operation was completed successfully in every case without conversion to open surgery or laparoscopy assisted surgery. The average operation time was 288.7 min. The average time to intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy was 54.3 min, with an average blood loss of 82.7 mL. The average number of retrieved lymph nodes per patient was 34.3. The distal and proximal margins were checked in frozen sectors, with R0 resection realized in each case. The average time until the first flatus was 3.7 d. The average time to start soft and liquid diets were 4.9 d and 6.6 d, respectively. The average postoperative hospital stay was 10.1 d.

| Type A (n = 18) | Type B (n = 22) | Type C (n = 10) | Type D (n = 31) | Total (n = 81) | |

| Operation time (min) | 305.6 ± 45.9 (250-380) | 266.8 ± 38.7 (230-360) | 278.0 ± 16.2 (250-300) | 297.9 ± 33.2 (240-420) | 288.7 ± 39.1 (230-420) |

| Anastomotic time (min) | 57.5 ± 18.5 (35-90) | 40.0 ± 11.2 (25-60) | 39.0 ± 3.9 (35-45) | 67.2 ± 18.8 (45-105) | 54.3 ± 19.9 (25-105) |

| Blood loss (mL) | 80.6 ± 29.4 (50-160) | 86.4 ± 39.7 (50-200) | 87.0 ± 24.5 (50-120) | 80.0 ± 32.5 (50-180) | 82.7 ± 32.7 (50-200) |

| Retrieved lymph nodes | 30.9 ± 5.8 (25-45) | 34.6 ± 4.1 (25-42) | 34.8 ± 6.1 (28-47) | 35.8 ± 11.4 (24-69) | 34.3 ± 8.2 (24-69) |

| First flatus after operation (d) | 4.2 ± 0.8 (3-5) | 3.6 ± 1.3 (2-7) | 3.4 ± 0.8 (2-5) | 3.6 ± 0.8 (2-5) | 3.7 ± 1.0 (2-7) |

| Liquid diet (d) | 5.2 ± 0.8 (4-6) | 4.9 ± 1.1 (3-7) | 4.6 ± 0.7 (4-6) | 4.7 ± 1.0 (3-7) | 4.9 ± 0.9 (3-7) |

| Soft diet (d) | 6.7 ± 1.3 (5-11) | 6.3 ± 1.1 (5-8) | 6.6 ± 0.8 (5-8) | 6.7 ± 2.1 (5-15) | 6.6 ± 1.6 (5-15) |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 10.9 ± 2.9 (9-20) | 10.2 ± 2.4 (8-17) | 10.1 ± 2.9 (8-18) | 9.6 ± 1.9 (7-17) | 10.1 ± 2.4 (7-20) |

Postoperative complications are listed in Table 3. The rate of postoperative morbidity was 17.3%, and there were no cases of postoperative death. Morbidity included anastomotic leakage (n = 1), anastomosis stricture (n = 3), intraluminal bleeding (n = 3), intestinal stasis (n = 2), abdominal abscess (n = 1), ileus (n = 1), lymphorrhea (n = 1), pulmonary infection (n = 1), and pulmonary embolism (n = 1). All complications were controlled by conservative treatment.

| Type A (n = 18) | Type B (n = 22) | Type C (n = 10) | Type D (n = 31) | Total (n = 81) | |

| Postoperative complications | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 14 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 1 | 1 | |||

| Anastomosis stricture | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Intraluminal bleeding | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Intestinal stasis | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Abdominal abscess | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ileus | 1 | 1 | |||

| Lymphorrhea | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pulmonary infection | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | 1 |

The use of laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) for gastric cancer has been gradually accepted because of its short-term benefit and the comparable oncological results as open gastrectomy. Most available studies on LG have focused on LDG for tumors located in the lower third of the stomach, which is the most common type in East Asia[12,13]. The incidence of tumors located in the upper and middle stomach has been evaluated recently and has resulted in an increased demand for LTG.

The major indications and technical aspects for LTG are similar to those for LDG. Several technical points relevant to the safety and feasibility of this technique should be addressed. The additional requirement set for the lymph nodes over the splenic hilum or any other short gastric artery represents a difficulty that has been encountered in fundamental gastrectomy. This requirement exists because the splenic vessels flow circuitously, with the branches substantially varying from one to another in deep locations. It is well known that hemorrhage or ischemia could occur because of splenic vascular injury during dissembling of lymph nodes neighboring splenic artery branches. Laparoscopy, compared with the laparotomy, permits the operator to finish dissembling the lymph nodes, which are quite clear, and assists in developing surgical safety. Therefore, the most obvious obstacle to LTG is still the difficulty involved in esophagojejunostomy, which can be performed extracorporeally or intracorporeally. Indeed, it is quite difficult in many cases to conduct the anastomosis via a mini-laparotomy, because space is quite restricted and narrow, specifically in obese victims with relatively thick abdominal walls or the specific tumors that exist in an upper location. It is for this reason that we started to conduct extracorporeal anatomosis, hoping to deal with the barricades of cumbersome reconstruction. We first introduced the use of intracorporeal anastomosis after LTG in 2007.

Two approaches for mechanical esophagojejunostomy have been used in LTG, linear stapling and circular stapling. Circular stapling enjoys similar merits as open total gastrectomy (OTG). The esophagojejunostomy can be performed successfully by adopting a circular stapler via a structure technique, which was hand-sewn in the first 18 patients of our series to mend the anvil that was applied in the esophageal stump. Based on our experience, the esophagus was not cut off initially, and the cardia was tightly tied with a band and then stretched down to expose the esophagus. Purse-string sutures were undertaken, and the anterior wall of the esophagus was then cut with a harmonic scalpel to form a half-circle. After placement of the anvil, the suture line was tightened and the esophagus was finally cut off with the harmonic scalpel. However, the circular stapler was inappropriate for placement during laparoscopic surgery due to its larger size and the absence of a matching tube. The pneumoperitoneum was vulnerable to its placement, and vision was unclear. Therefore, it was not an ideal method and may have resulted in a higher rate of postoperative complications[14,15], especially in our early experience. Thus, a novel transorally inserted anvil (OrVil; Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States) was introduced to address the challenge of anvil placement[16]. OrVil is not only good in terms of operation safety and treatment effects but also in the reduction in operation time. However, due to its high cost, possibility of bacterial contamination in the abdominal cavity, and injury to the esophageal mucosa, this method is adopted only in some specialized medical centers.

A linear stapler was used for side-to-side esophagojejunostomy. This method was first reported by Uyama et al[17] and was modified by Wang et al[18]. Circular stapling was performed to isolate separately the esophagus and jejunum prior to anastomosis. The linear stapler was inserted at the two ends to complete the anastomosis and then closed the collective opening. Benefits of the linear stapling method involved no initial dissection of the jejunum and esophagus to pull down the esophagus. Thus the esophagus did not need to be completely retracted to the chest; and instead, the specimen was removed, and the common opening was closed together after completion of the anastomosis, economizing the staplers. This method was simple to perform, and the anastomotic stoma was bigger, which may have helped avoid postoperative complications, such as anastomotic stenosis. With regard to specific surgical methods, some surgeons advise that the position taken by the esophageal and jejunum stump should be fixed, adopting at least one stitch prior to the endoscopic linear staple that has been applied[19]. However, in our practice, it has been found that the suture angulates and suspends the jejunum, posing great challenges to the endoscopic linear stapler, sacrificing the mobility of the jejunum. According to our experience, it is more favorable to place one arm of the endoscopic linear stapler, which has been applied into the opening of the jejunum, and to clamp the two arms with no stapling. Later, with the assistance of the stapler, attracting the jejunum close to the esophageal stump’s rear and then unveiling the two arms to replace the second one finishes the anastomosis following the apposition, which has been proven to be quite satisfactory. However, even using this approach, possible issues remain, including taking the distortion over the mesenterium and Roux limb as well as the slipping over the esophagojejunal anastonomic site applied in the comparative lower mediastinum. The surgical margin is limited as a longer esophageal stump should be reserved.

The delta-shaped esophagojejunostomy provides a considerable lumen, regardless of the size of the esophageal stump. More importantly, as a long esophageal stump and anastomosed intestine are not required, this technique achieves less flexion in order to provide enough blood supply for the anastomotic site, thus decreasing the risk of anastomotic leakage. However, surgeons of the technique should have proficient laparoscopic suturing skills, or the outcome of the anastomosis will be impacted because of the unfavorable apposition of the average opening. The assistant should maneuver the stay suture efficiently to ensure that the stapler is applied adequately on all layers of the esophagus[20]. Hand-sewn end-to-side esophagojejunostomy overcomes the limitations caused by the mechanical method. The suturing process can be clearly observed under high definition laparoscopy, and the anastomosis is reliable. The operating space is large, and there is no tension in the whole anastomosis procedure, thus avoiding injury. More importantly, this method completes the anastomosis after removal of the specimen, as the anastomosis can be performed after negative margins are confirmed using intraoperative frozen sections. This method does not require a long esophageal stump. In patients with a positive resection margin, the removal length can be expanded appropriately to confirm a negative resection margin. Therefore, the R0 resection can be improved, and the conversion rate to laparotomy is reduced. However, the hand-sewn method requires operators with extensive experience in laparoscopic suturing, which may increase surgery time. In our experience, progressive practice (from practice on the simulator to practice on animal models and simple suture under laparoscopy, and finally to laparoscopic gastrointestinal anastomosis) can effectively shorten the learning curve. At the same time, the application of new laparoscopic instruments can simplify intracorporeal hand-sewn suturing. Knotless barbed sutures (V-LocTM; Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States) can reduce the time of anastomosis and can ensure the safety of anastomosis, with no need for permanent traction during the whole anastomosis procedure.

We recommend that the reconstruction method using a stapler should be selected on the basis of tumor location. In our experience, side-to-side or delta-shaped esophagojejunostomy using a linear stapler can be adopted for patients with lesions in the body and fundus of the stomach as well as the lower cardia. For patients with lesions in the upper and middle cardia, end-to-side esophagojejunostomy using a circular stapler is chosen to ensure a negative surgical margin. In addition, if the surgeon is well experienced with the laparoscopic hand-sewn technique, it can be used after total gastrectomy, regardless of tumor location.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that LTG facilitated with intracorporeal anastomosis is feasible and safe, leading to quite favorable contemporary results. However, the clinical efficacy should be demonstrated further in a perfectly designed randomized controlled clinical trial. The choice of approach for intracorporeal anastomosis depends mainly on the surgeon’s preference and experience.

Laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer has gained wide popularity in the past few decades. However, laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) is rarely performed due to some technical difficulties.

It is important to study the feasibility and safety of LTG with intracorporeal anastomosis. New approaches are needed in order to improve the surgical experience for patients and provide easier and simpler surgical procedures. Based on our study, LTG with intracorporeal anastomosis is likely to be the best option.

This study demonstrated that LTG with intracorporeal anastomosis can be a safe and favorable alternative to open gastrectomy and laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy. Furthermore, several esophagojejunostomy methods are available, depending on patients’ condition and surgeon preference.

LTG with intracorporeal anastomosis can be safely performed with the proper esophagojejunostomy method.

LTG with intracorporeal anastomosis can be safely performed with quite favorable results. However, the clinical efficacy should be demonstrated with more well designed studies.

The authors concluded that LTG with intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy using laparoscopic staplers was safe and feasible for patients with gastric cancer. This paper is well studied and well written.

P- Reviewer: Murata A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146-148. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Eom BW, Kim YW, Lee SE, Ryu KW, Lee JH, Yoon HM, Cho SJ, Kook MC, Kim SJ. Survival and surgical outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: case-control study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3273-3281. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li F, Zhang R, Liang H, Liu H, Quan J. The pattern and risk factors of recurrence of proximal gastric cancer after curative resection. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:130-135. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oki E, Sakaguchi Y, Ohgaki K, Saeki H, Chinen Y, Minami K, Sakamoto Y, Toh Y, Kusumoto T, Okamura T. The impact of obesity on the use of a totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:108-112. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang W, Chen K, Xu XW, Pan Y, Mou YP. Case-matched comparison of laparoscopy-assisted and open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3672-3677. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xu X, Chen K, Zhou W, Zhang R, Wang J, Wu D, Mou Y. Laparoscopic transgastric resection of gastric submucosal tumors located near the esophagogastric junction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1570-1575. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen K, Xu X, Mou Y, Pan Y, Zhang R, Zhou Y, Wu D, Huang C. Totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy and Billroth II gastrojejunostomy for gastric cancer: short- and medium-term results of 139 consecutive cases from a single institution. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:1462-1470. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen K, Mou YP, Xu XW, Cai JQ, Wu D, Pan Y, Zhang RC. Short-term surgical and long-term survival outcomes after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang RC, Yan JF, Xu XW, Chen K, Ajoodhea H, Mou YP. Laparoscopic vs open distal pancreatectomy for solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6272-6277. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yan JF, Xu XW, Jin WW, Huang CJ, Chen K, Zhang RC, Harsha A, Mou YP. Laparoscopic spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic neoplasms: a retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13966-13972. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang MZ, Xu XW, Mou YP, Yan JF, Zhu YP, Zhang RC, Zhou YC, Chen K, Jin WW, Matro E. Resection of a cholangiocarcinoma via laparoscopic hepatopancreato- duodenectomy: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17260-17264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jeong O, Park YK. Clinicopathological features and surgical treatment of gastric cancer in South Korea: the results of 2009 nationwide survey on surgically treated gastric cancer patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:69-77. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 185] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kitano S, Shiraishi N. Current status of laparoscopic gastrectomy for cancer in Japan. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:182-185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jeong GA, Cho GS, Kim HH, Lee HJ, Ryu SW, Song KY. Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Surgery. 2009;146:469-474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wada N, Kurokawa Y, Takiguchi S, Takahashi T, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Nakajima K, Mori M, Doki Y. Feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy in patients with clinical stage I gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:137-140. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jeong O, Park YK. Intracorporeal circular stapling esophagojejunostomy using the transorally inserted anvil (OrVil) after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2624-2630. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 135] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Uyama I, Sugioka A, Fujita J, Komori Y, Matsui H, Hasumi A. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with distal pancreatosplenectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2:230-234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ziqiang W, ZhiMin C, Jun C, Xiao L, Huaxing L, PeiWu Y. A modified method of laparoscopic side-to-side esophagojejunal anastomosis: report of 14 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2091-2094. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bouras G, Lee SW, Nomura E, Tokuhara T, Nitta T, Yoshinaka R, Tsunemi S, Tanigawa N. Surgical outcomes from laparoscopic distal gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction: evolution in a totally intracorporeal technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:37-41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okushiba S, Kawarada Y, Shichinohe T, Manase H, Kitashiro S, Katoh H. Esophageal delta-shaped anastomosis: a new method of stapled anastomosis for the cervical esophagus and digestive tract. Surg Today. 2005;35:341-344. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |