Published online Sep 27, 2013. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i9.462

Revised: August 7, 2013

Accepted: August 16, 2013

Published online: September 27, 2013

Nonparasitic hepatic cysts consist of a heterogeneous group of disorders, which differ in etiology, prevalence, and manifestations. With improving diagnostic techniques, hepatic cysts are becoming more common. Recent advancements in minimally invasive technology created a new Era in the management of hepatic cystic disease. Herein, the most current recommendations for management of noninfectious hepatic cysts are described, thereby discussing differential diagnosis, new therapeutic modalities and outcomes.

Core tip: Nonparasitic hepatic cysts consist of a broad spectrum of entities ranging from benign developmental cysts to malignant neoplasms. With recent advancements in diagnostic studies, hepatic cysts are becoming more frequent and better understanding of risk factors, management and long-term outcomes, and further development of current therapeutic modalities are needed.

- Citation: Macedo FI. Current management of noninfectious hepatic cystic lesions: A review of the literature. World J Hepatol 2013; 5(9): 462-469

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v5/i9/462.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v5.i9.462

Nonparasitic hepatic cysts consist of a heterogeneous group of disorders, which differ in etiology, prevalence, and manifestations, from simple cysts to neoplastic lesions. Differential diagnoses of hepatic cysts include: infectious (hydatid cyst, amebic and pyogenic abscesses), and noninfectious [simple cyst, polycystic liver disease (PCLD), cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma and hepatocarcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma, intrahepatic pseudocysts secondary to pancreatitis, liver hematomas, biliomas, ciliated hepatic foregut cyst] (Table 1). Sometimes, these lesions are not easily differentiated at initial presentation or by imaging studies, and management can become challenging. With improving diagnostic techniques and minimally invasive technology, the management of hepatic cystic disease continues to evolve. We, herein, describe the most current management of noninfectious hepatic cysts, thereby discussing differential diagnosis, treatment options and outcomes.

| Infectious | |

| Parasitic | Nonparasitic |

| Hydatic cyst | Pyogenic liver abscesses |

| Amebic abscess | |

| Non-infectious | |

| Simple cyst | Partially cystic component |

| PCLD | HCC |

| Cystadenoma | Cholangiocarcinoma |

| Cystadenocarcinoma | Intrahepatic pseudocysts (pancreatitis) |

| Caroli's disease | Bilomas |

| Peribiliary cyst | Post-traumatic hematoma |

| Cystic metastases | Giant hemangioma |

| Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst | |

| Congenital (embryonal sarcoma) |

Simple hepatic cyst is a biliary malformation, which does not have communication with the intrahepatic biliary tree. Most cysts measure less than 3 cm and are asymptomatic. Microscopically, they are lined by a single layer of cuboid or columnar epithelial cells, resembling biliary epithelial cells. Its origin is derived from aberrant bile ducts that have lost communication with the biliary tree, and continue to secrete intraluminal fluid[1]. The incidence is larger in adults older than 50 years, with female to male ratio 1.5:1, and prevalence is around 18% in adult population[2]. In the majority of patients, liver function tests are within the normal range. Asymptomatic single liver cysts, even when large, do not require treatment or surveillance. Ultrasound (US) is the best imaging modality for recognizing simple cysts, which appear as a circular or oval, anechoic lesion with smooth borders and acoustic posterior enhancement and without septations[3]. Further imaging studies, including computed tomography (CT), are not routinely required and show non-septated, round and water-dense lesions. In symptomatic patients requiring intervention, either sclerotherapy or surgical fenestration, hydatid cyst should be ruled out in all cases before the operation by serology, and by the patient history of recent travel to endemic areas. In lesions suspicious for cystadenoma, the recommended therapy is surgical resection, as this lesion has malignant potential[4-8].

Sclerotherapy consists of the destruction of the epithelial lining of the inner surface of the wall to disrupt the intracystic fluid secretion[9-11]. Under general anesthesia, drainage catheter is introduced by Seldinger technique and under ultrasound guidance, followed by injection of water-soluble contrast to rule out communication with adjacent bile duct or peritoneal cavity. Sclerosing agents include ethanol, minocycline hydrochloride and ethanolamine oleate[12]. The amount of alcohol injection is limited (100-200 mL) due to the risk of alcohol intoxication, and retention lasts usually between 120-240 min[13]. The solution is then aspirated before the catheter is removed. The size of the cyst does not play a role in the amount of sclerosing agent given because after cyst collapses, sclerosant will come into contact with the cyst inner wall. Contraindications of sclerotherapy include intracystic bleeding and fistula between the cyst and biliary tree or peritoneum. The optimal efficacy may be seen up to a year after sclerotherapy, and symptomatic recurrence rate is around 20% after 4 mo[14]. Due to high recurrence rates, management by aspiration followed by sclerotherapy should be reserved for those patients who are not eligible for surgery and general anesthesia[15].

Surgical fenestration, also known as unroofing, consists of an excision of the roof of the cyst to provide communication between the cyst and the peritoneal cavity. Limitations include cysts involving segments VII or VIII, which have higher recurrence rates due to anatomical position. Hemorrhage and biliary injury are, although rare, possible complications[16]. There is no associated mortality and morbidity ranges from 0%-15%, with reoperation rates at 9%[17]. There is no randomized prospective study to date comparing fenestration and sclerotherapy. In most centers, sclerotherapy is attempted first as a noninvasive option, and laparoscopic fenestration is usually indicated in refractory cases. Laparoscopy has become the procedure of choice for deroofing because is associated with significant reduction in hospital stay, postoperative pain and morbidity, and decreased blood loss[15,18]. To avoid recurrence, it is necessary to resect as much of the wall as possible to prevent closure of the remnant wall and reaccumulation of cyst fluid. However, complete resection of the cyst is not necessary and is associated with higher complication rates. Transposition of omental patch to the cyst bed has been advocated as a means of diminishing recurrence, especially in segments VII and VIII, where early adhesion of the cyst wall to either the diaphragm or abdominal wall may lead to refilling, however this still need to be confirmed by controlled studies[19].

PCLD is a genetic disease responsible for the development of multiple hepatic cysts. It presents in two forms, with or without autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)[20]. Both have an autosomal dominant transmission and similar clinical presentation. PCLD associated with ADPKD is linked with mutations in the PKD1 (short arm of chromosome 16, encoding polycystin-1) or PKD2 gene (chromosome 4, encoding polycystin-2), whereas isolated PCLD is associated with heterozygous mutation in PRKC-SH or SEC63 genes[21-26]. Overall prevalence is the same in gender, but female population is associated with more severe liver disease[27]. Pregnancy, multiparity, and use of steroids further increase the risk for severe hepatic cystic disease[28].

In most patients, cysts are small and asymptomatic; when present, symptoms are related mainly to the volume of enlarged liver rather than the volume of a specific cyst, and include abdominal distension, dyspnea, pain and early satiety[29]. US shows multiple, fluid-filled, round or oval cysts with sharp margins. Cysts do not show contrast enhancement, and it may be extremely difficult to identify vascular and biliary structures adjacent to the cysts. CT scan shows fluid attenuation with no contrast enhancement, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates hyperintense on T2-weighted and hypointense on T1-weighted images. Gigot’s classification[30] is used for staging based on CT findings: type I, less than 10 large cysts; type II, diffuse involvement of liver parenchyma, but with remaining large areas of noncystic liver parenchyma; and type III, massive, diffuse involvement of liver parenchyma with only a few areas of normal tissue between cysts. Complications are uncommon and include bleeding, rupture and infection of cysts[31]. The most severe complication is bacterial infection, especially those under dialysis for ADPKD or in immunosuppressed patients after renal transplantation[32-37]. This is usually managed with aspiration and drainage, and antibiotics. Cholestasis secondary to compression of adjacent biliary duct also may ensue, as well as portal hypertension, resulting from portal or hepatic vein compression[38]. The incidence of concurrent cerebral aneurysms is 8%, whereas mitral valve prolapse occurs in 25% in those with PCLD associated with ADPKD[39].

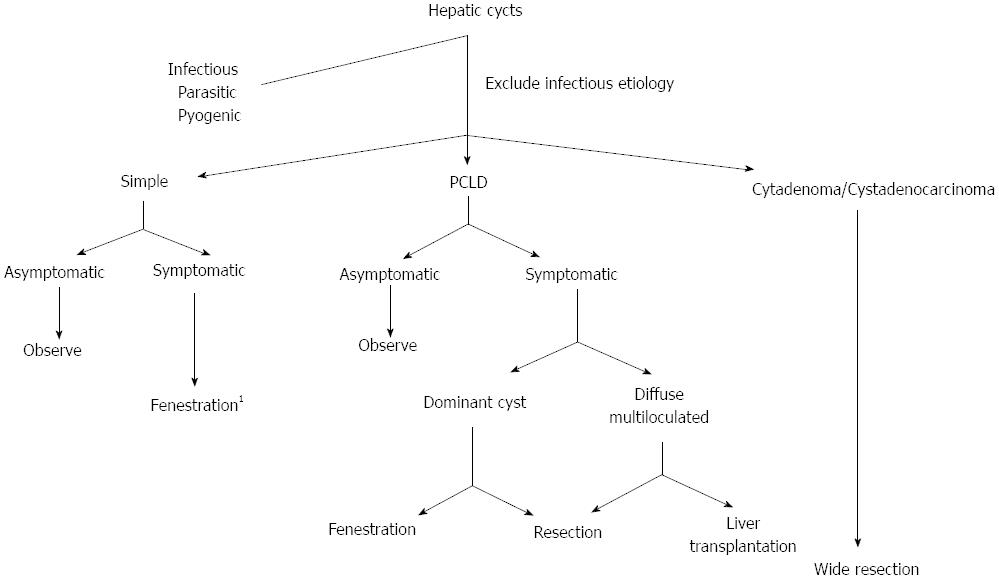

Most current therapies are invasive and consist of surgical removal or emptying of cysts aiming at decompression and reduction of the liver size. Medical management has been proposed in advanced PCLD with diffuse disease[40,41]. The efficacy of conservative management is still under investigation. Two recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that lanreotide, a long-acting somatostatin analogue, was associated with a limited reduction of liver volume in both types of PCLD, measured by CT or MRI as a primary endpoint[42-46]. Liver volume decreased by 2.9% in the lanreotide group, but increased by 1.6% in the placebo group[41]. Sclerotherapy and laparoscopic fenestration showed ineffective in the management of PCLD[47]. Current surgical options include: open fenestration, liver resection, or liver transplantation (Figure 1). Transcatheter embolization has been recently proposed, targeting at decreasing arterial supply to the cyst. Although improvement of symptoms and significant reduction of liver size were observed in most patients, the limited experience in such technically demanding procedure still pose limitation to widespread use[48].

Partial liver resection associated with fenestration of the remnant liver has been historically proposed and, although highly successful is some patients, it is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, and its indications are becoming more selective. Liver transplantation is the only curative modality, and is the only option in patients with anticipated limited efficacy by liver resection[49-51] (Figure 1).

The appropriate surgical option may be defined based on Gigot’s classification; in type I, which corresponds only 10% of cases, laparoscopic fenestration is recommended as first option; in type II, open fenestration is usually implemented; and type III is a contraindication to fenestration and requires resection or liver transplantation in symptomatic cases. If liver transplantation is anticipated, prior fenestration or resection should be avoided to decrease the risk of transplantation[52-56].

Caroli’s disease is a rare congenital disorder characterized by multiple segmental intrahepatic cystic dilatations, firstly described in 1958 by Caroli et al[57]. It has an autosomal recessive inheritance linked to mutation in PKHD1 gene, leading to persistent embryonic bile ducts at different levels of the intrahepatic biliary tree. It is also classified as type V choledochal cyst by Todani classification[58]. As opposed to PCLD, cystic lesions are irregular in shape, fusiform or saccular, and communicate with biliary tree. Patients usually present with recurrent episodes of cholangitis of unknown source, intrahepatic lithiasis and cholelithiasis[59-62]. In the presence of congenital hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension, it is often termed Caroli’s syndrome[63,64]. US shows intrahepatic cystic anechoic areas in which fibrovascular bundles, stones and linear bridging or septum may be present[65]. The gold standard for diagnosis is direct visualization of the biliary tree, either endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiography (PTC)[66]. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an emerging modality for diagnosis of Caroli’s disease[67-69]. It has several advantages: noninvasive, readily available, and ability to visualize the entire biliary tract[70]. The characteristic appearance on MRCP is the “string of beads” pattern of the ectatic intrahepatic bile ducts. Most common complications of Caroli’s disease include cholangitis, sepsis, choledocholithiasis and hepatic abscess. At advanced stages, it may cause hepatic fibrosis with increased risks for cholangiocarcinoma and liver failure[71].

Management consists of treatment of acute cholangitis and control of sepsis with broad-spectrum antibiotics, ursodeoxycolic acid for hepatolithiasis, and palliative biliary drainage, either via PTC or ERCP with or without sphincterotomy. Patients with frequent cholangitis should undergo endoscopic surveillance every 6 to 12 mo[72]. Surgical options include partial liver resection for segmental or unilobar involvement[73], or liver transplantation, which is the only curative treatment[74]. Kassahun et al[75] described one of the largest experience with patients undergoing liver resection with or without biliodigestive anastomosis for unilobar disease with 84% of patients remained asymptomatic over 4 years follow-up period. Liver transplantation should be offered early in cases of recurrent cholangitis and suspicious for early malignant transformation of the biliary tract. The European transplant registry reported patient survival around 76% at 5 years after transplantation[76]. In diffuse disease and deemed to liver transplantation, bypass procedures, either choledochojejunostomy or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy may help palliate symptoms and increase survival.

Hepatic cystadenoma is a rare benign tumor of unknown etiology, and accounts for 5% of hepatic cystic lesions. Most lesions arise within the intrahepatic bile ducts and occur more commonly in females older than 40 years of age. It may present incidentally or if large, patients may present with jaundice and cholangitis for adjacent biliary compression[77]. Cystadenoma should be considered in any patient presenting with recurrent liver cysts after fenestration. Diagnostic imaging studies include a multiloculated lesion with internal septations, thickened and irregular wall, mural nodules and papillary projections, calcifications and wall enhancements[78]. Preoperative planning with direct visualization of biliary anatomy is necessary in most cases with ERCP or PTC, which confirm biliary tree communication[79-81]. The role of MRCP for preoperative imaging still needs to be defined[81]. It is challenging to distinguish the lesions from hepatic cystadenocarcinomas based on current diagnostic studies[82]. Irregular wall enhancement and the presence of papillary projections should increase suspicion for biliary cystadenocarcinoma[83]. Abnormal serum markers, such as CA 19-9 levels and carcinoembryonic antigen, may favor malignant transformation, although this is a variable finding. The current treatment modality is open or laparoscopic liver resection due to the risk of malignancy in all suspected cystadenomas[84-86] (Figure 1). Frozen sections are not reliable at evaluating these lesions and definitely excluding cystadenocarcinoma. Clear margins are advised due to the risk for synchronous carcinoma or foci of carcinoma in situ.

Biliary cystadenocarcinoma is a rare cystic neoplasm of unknown etiology, usually arising intrahepatic or, less frequently, in the extrahepatic bile ducts, and account for 0.41% of hepatic neoplasias[87]. The majority of these tumors are slow growing, and at the time of presentation, tumor is large with mean diameter at 12 cm, causing abdominal pain, intermittent jaundice, weight loss and ascites[88]. Current imaging studies are unable to confirm cystadenocarcinomas, however suggestive morphological findings may include: multilocular cyst mass with mural nodules at the periphery, and coarse calcifications. MRI further characterizes the content of the different locules not as serous fluid, but as a complex collection with proteinaceous material and hemorrhagic debris[89-91]. Preoperative fine-needle aspiration or needle biopsy is contraindicated due to the risk of fluid spilling into abdominal cavity and development of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Overall prognosis is better than HCC or cholangiocarcinoma with 5 years survival rate at 57% after resection, compared with 40% in HCC, and 22% in cholangiocarcinoma[92]. The only treatment option is formal hepatic resection which has acceptable recurrence rates (10%)[91,93] (Figure 1). In metastatic disease (20%), chemo- and/or radio-therapy have been advocated with doxorubicin and 5-FU, however results are yet limited[94].

Although uncommon, HCC and cholangiocarcinoma may occasionally be cystic, especially in rapidly growing tumors. Giant hemangiomas may rarely present as partly cystic, which corresponds to noncirculating areas, and kinetic of contrast enhancement is typical. Intrahepatic pseudocyst secondary from acute pancreatitis is extremely rare with less than 20 cases reported[95]. It may be seen in the left lobe along the lesser omentum, or in the right lobe along the portal vein. Pancreatic MRI may be useful to identify rupture of the pancreatic duct[1]. Liver hematomas may present as cystic lesions in CT scan or US after liver surgery or trauma, especially after clots liquefy at a later phase. They are spontaneously echogenic on US, hyperdense on CT scan, hyperintense on T1-weighted and hypointense on T2-weighted MRI sequences. Bilomas are cystic lesions surrounded by a fibrous capsule that can occur adjacent to the liver parenchyma secondary from traumatic, iatrogenic or spontaneous lesions.

Cystic hepatic metastases are rare, arising mostly from neuroendocrine, tumors, sarcoma, melanomas or pancreatic cystadenocarcinomas. The presence of increased peripheral vascularization and multiple lesions should rise suspicious for this rare lesion.

Peribiliary cysts arise from cystic enlargement of peribiliary glands, mostly occurring in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension or after liver transplantation. The cysts are located along common bile duct or within portal tracts, and are usually small and asymptomatic[96].

Ciliated hepatic foregut cysts are benign lesions that have been described in most gastrointestinal organs, including the liver[97,98]. They form where the foregut extends during the embryonic period, and are extremely rare. It consists of four-layer border; pseudostratified, ciliated columnar epithelium covering a subepithelial connective tissue, smooth muscle bundles, and an outer fibrous capsule, and usually located in the anterior surface of the liver. Most cases are asymptomatic and incidentally found during abdominal imaging studies, however patients may present with epigastric or right upper quadrant pain[99]. Imaging characteristics include: predominance in segment IV, small size, subcapsular location. Two thirds are hypoechoic on US, hypodense on CT, and highly hyperintense on T2-weighted images on MRI[97,100].

Biliary hamartomas (also known as von Meyenburg complexes) are asymptomatic lesions, usually discovered incidentally during liver surgery[101]. They may be associated with Caroli’s disease, PCLD and congenital hepatic fibrosis, and identification is clinically important because may be misdiagnosed as liver metastasis[102].

Most hepatic cysts are benign, small, and asymptomatic lesions that are diagnosed incidentally and require no intervention, whereas large, symptomatic or neoplastic cysts need further treatment. Symptomatic simple cyst should be managed with laparoscopic unroofing; PCLD can be managed, in most cases, with partial resection; or liver transplantation for advanced multiloculated disease. Biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas require complete resection with clear margins. With recent advancements in diagnostic studies, hepatic cysts are becoming more common and better understanding of risk factors; long-term outcomes and further development of current therapeutic modalities are needed.

P- Reviewers Banales JM, Inamori M S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Wu HL

| 1. | Farges O, Aussilhou B. Simple cysts and polycystic liver disease: surgical and non-surgical management. Blumgart’s Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Saunders 2012; 1066-1079. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Carrim ZI, Murchison JT. The prevalence of simple renal and hepatic cysts detected by spiral computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:626-629. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liang P, Cao B, Wang Y, Yu X, Yu D, Dong B. Differential diagnosis of hepatic cystic lesions with gray-scale and color Doppler sonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:100-105. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seo JK, Kim SH, Lee SH, Park JK, Woo SM, Jeong JB, Hwang JH, Ryu JK, Kim JW, Jeong SH. Appropriate diagnosis of biliary cystic tumors: comparison with atypical hepatic simple cysts. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:989-996. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Vachha B, Sun MR, Siewert B, Eisenberg RL. Cystic lesions of the liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W355-W366. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Choi HK, Lee JK, Lee KH, Lee KT, Rhee JC, Kim KH, Jang KT, Kim SH, Park Y. Differential diagnosis for intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and hepatic simple cyst: significance of cystic fluid analysis and radiologic findings. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:289-293. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ludwig K. Solder secure bond. Dent Labor (Munch). 1990;38:1239-1400, 1242, 1245. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kitajima Y, Okayama Y, Hirai M, Hayashi K, Imai H, Okamoto T, Aoki S, Akita S, Gotoh K, Ohara H. Intracystic hemorrhage of a simple liver cyst mimicking a biliary cystadenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:190-193. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moorthy K, Mihssin N, Houghton PW. The management of simple hepatic cysts: sclerotherapy or laparoscopic fenestration. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:409-414. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Fiamingo P, Tedeschi U, Veroux M, Cillo U, Brolese A, Da Rold A, Madia C, Zanus G, D’Amico DF. Laparoscopic treatment of simple hepatic cysts and polycystic liver disease. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:623-626. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hansman MF, Ryan JA, Holmes JH, Hogan S, Lee FT, Kramer D, Biehl T. Management and long-term follow-up of hepatic cysts. Am J Surg. 2001;181:404-410. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nakaoka R, Das K, Kudo M, Chung H, Innoue T. Percutaneous aspiration and ethanolamine oleate sclerotherapy for sustained resolution of symptomatic polycystic liver disease: an initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1540-1545. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang CF, Liang HL, Pan HB, Lin YH, Mok KT, Lo GH, Lai KH. Single-session prolonged alcohol-retention sclerotherapy for large hepatic cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:940-943. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Erdogan D, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, Busch OR, Lameris JS, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Results of percutaneous sclerotherapy and surgical treatment in patients with symptomatic simple liver cysts and polycystic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3095-3100. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Treckmann JW, Paul A, Sgourakis G, Heuer M, Wandelt M, Sotiropoulos GC. Surgical treatment of nonparasitic cysts of the liver: open versus laparoscopic treatment. Am J Surg. 2010;199:776-781. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gigot JF, Legrand M, Hubens G, de Canniere L, Wibin E, Deweer F, Druart ML, Bertrand C, Devriendt H, Droissart R. Laparoscopic treatment of nonparasitic liver cysts: adequate selection of patients and surgical technique. World J Surg. 1996;20:556-561. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Loehe F, Globke B, Marnoto R, Bruns CJ, Graeb C, Winter H, Jauch KW, Angele MK. Long-term results after surgical treatment of nonparasitic hepatic cysts. Am J Surg. 2010;200:23-31. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gamblin TC, Holloway SE, Heckman JT, Geller DA. Laparoscopic resection of benign hepatic cysts: a new standard. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:731-736. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Emmermann A, Zornig C, Lloyd DM, Peiper M, Bloechle C, Broelsch CE. Laparoscopic treatment of nonparasitic cysts of the liver with omental transposition flap. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:734-736. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Tahvanainen P, Tahvanainen E, Reijonen H, Halme L, Kaariainen H, Hockrstedt K. Polycystic liver disease is genetically heterogenous: clinical and linkage studies in eight finnish families. J Hepatol. 2003;38:39-43. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Drenth JP, Martina JA, Te Morsche RH, Jansen JB, Bonifacino JS. Molecular characterization of hepatocystin, the protein that is defective in autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterol. 2004;126:1819-1827. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Drenth JP, te Morsche RH, Smink R, Bonifacino JS, Jansen JB. Germline mutations in PRKCSH are associated with autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33:345-347. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 156] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li A, Davila S, Furu L, Qian Q, Tian X, Kamath PS, King BF, Torres VE, Somlo S. Mutations in PRKCSH cause isolated autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:691-703. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 132] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Waanders E, Venselaar H, te Morsche RH, de Koning DB, Kamath PS, Torres VE, Somlo S, Drenth JP. Secondary and tertiary structure modeling reveals effects of novel mutations in polycystic liver disease genes PRKCSH and SEC63. Clin Genet. 2010;78:47-56. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rossetti S, Consugar MB, Chapman AB, Torres VE, Guay-Woodford LM, Grantham JJ, Bennett WM, Meyers CM, Walker DL, Bae K. Comprehensive molecular diagnostics in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2143-2160. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Janssen MJ, Waanders E, Woudenberg J, Lefeber DJ, Drenth JP. Congenital disorders of glycosylation in hepatology: the example of polycystic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2010;52:432–440. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1287-1301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 957] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 910] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sherstha R, McKinley C, Russ P, Scherzinger A, Bronner T, Showalter R, Everson GT. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy selectivelt stimulates hepatic enlargement in women with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:1282-1286. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Van Keimpema L, De Koning DB, Van Hoek B, Van Den Berg AP, Van Oijen MG, De Man RA, Nevens F, Drenth JP. Patients with isolated polycystic liver disease referred to liver centres: clinical characterization of 137 cases. Liver Int. 2011;31:92-98. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Gigot JF, Jadoul P, Que F, Van Beers BE, Etienne J, Horsmans Y, Collard A, Geubel A, Pringot J, Kestens PJ. Adult polycystic liver disease: is fenestration the most adequate operation for long-term management. Ann Surg. 1997;225:286-294. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Drenth JP, Chrispijn M, Bergmann C. Congenital fibrocystic liver diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:573-584. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Qian Q. Isolated polycystic liver disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:181-189. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Torres VE, Harris PC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney Int. 2009;76:149-168. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Perrone RD. Extrarenal manifestations of ADPKD. Kidney Int. 1997;51:2022-2036. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Harris PC, Bae KT, Rossetti S, Torres VE, Grantham JJ, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, King BF, Wetzel LH, Baumgarten DA. Cyst number but not the rate of cystic growth is associated with the mutated gene in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3013-3019. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Qian Q, Li A, King BF, Kamath PS, Lager DJ, Huston J, Shub C, Davila S, Somlo S, Torres VE. Clinical profile of autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:164-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pirson Y. Extrarenal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:173-180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sato Y, Yokoyama N, Suzuki S, Tani T, Nomoto M, Hatakeyama K. Double selective shunting for esophagogastric and rectal varices in portal hypertension due to congenital hepatic polycystic disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1528-1530. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Pirson Y, Chauveau D, Torres V. Management of cerebral aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:269-276. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | van Keimpema L, Höckerstedt K. Treatment of polycystic liver disease. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1379-1380. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gevers TJ, Drenth JP. Somatostatin analogues for treatment of polycystic liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:294-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Van Keimpema L, Nevens F, Vanslembrouck R, van Oijen MG, Hoffman AL, Dekker HM, de Man RA, Drenth JP. Lanreotide reduced the volume of polycystic liver: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1661-1668. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 174] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, Kubly VJ, Bergstralh EJ, Li X, Kim B, King BF, Glockner J, Holmes DR. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1052-1061. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 222] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Caroli A, Antiga L, Cafaro M, Fasolini G, Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. Reducing polycystic liver volume in ADPKD: effects of somatostatin analogue octreotide. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:783-789. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page L, Holmes DR, Li X, Bergstralh EJ, Irazabal MV, Kim B, King BF, Glockner JF. Somatostatin analog therapy for severe polycystic liver disease: results after 2 years. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3532-3539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | van Keimpema L, de Man RA, Drenth JP. Somatostatin analogues reduce liver volume in polycystic liver disease. Gut. 2008;57:1338-1339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Robinson TN, Stiegmann GV, Everson . Laparoscopic palliation of polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;19:130-132. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Takei R, Ubara Y, Hoshino J, Higa Y, Suwabe T, Sogawa Y, Nomura K, Nakanishi S, Sawa N, Katori H. Percutaneous transcatheter hepatic artery embolization for liver cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:744-752. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Russell RT, Pinson CW. Surgical management of polycystic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5052-5059. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Drenth JP, Chrispijn M, Nagorney DM, Kamath PS, Torres VE. Medical and surgical treatment options for polycystic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:2223-2230. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 146] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Temmerman F, Missiaen L, Bammens B, Laleman W, Cassiman D, Verslype C, van Pelt J, Nevens F. Systematic review: the pathophysiology and management of polycystic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:702-713. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Farges O, Bismuth H. Fenestration in the management of polycystic liver disease. World J Surg. 1995;19:25-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Que F, Nagorney DM, Gross JB, Torres VE. Liver resection and cyst fenestration in the treatment of severe polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:487-494. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Lang H, von Woellwarth J, Oldhafer KJ, Behrend M, Schlitt HJ, Nashan B, Pichlmayr R. Liver transplantation in patients with polycystic liver disease. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2832-2833. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ueno T, Barri YM, Netto GJ, Martin A, Onaca N, Sanchez EQ, Chinnakotla S, Randall HB, Dawson S, Levy MF. Liver and kidney transplantation for polycystic liver and kidney-renal function and outcome. Transplantation. 2006;82:501-507. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Pirenne J, Aerts R, Yoong K, Gunson B, Koshiba T, Fourneau I, Mayer D, Buckels J, Mirza D, Roskams T. Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:238-245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Caroli J, Soupault R, Kossakowski J, Plocker L, Paradowska . Congenital polycystic dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, attempt at classification. Sem Hop. 1958;34:488-495. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 58. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;143:263-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 934] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 768] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Yonem O, Bayraktar Y. Clinical characteristics of Caroli’s syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1934-1937. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Ciambotti GF, Ravi J, Abrol RP, Arya V. Right-sided monolobar Caroli’s disease with intrahepatic stones: nonsurgical management with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:761-764. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 61. | Schiano TD, Fiel MI, Miller CM, Bodenheimer HC, Min AD. Adult presentation of Caroli’s syndrome treated with orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1938-1940. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 62. | Tsuchida Y, Sato T, Sanjo K, Etoh T, Hata K, Terawaki K, Suzuki I, Kawarasaki H, Idezuki Y, Nakagome Y. Evaluation of long-term results of Caroli’s disease: 21 years’ observation of a family with autosomal “dominant” inheritance, and review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:175-181. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 63. | Kerkar N, Norton K, Suchy FJ. The hepatic fibrocystic diseases. Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10:55-71, v-vi. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Yönem O, Ozkayar N, Balkanci F, Harmanci O, Sökmensüer C, Ersoy O, Bayraktar Y. Is congenital hepatic fibrosis a pure liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1253-1259. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Saeian K. Caroli’s disease: identification and treatment strategy. Cur Gastroenterol Opin. 2007;9:151-155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Levy AD, Rohrmann CA, Murakata LA, Lonergan GJ. Caroli’s disease: radiologic spectrum with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1053-1057. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Pavone P, Laghi A, Catalano C, Materia A, Basso N, Passariello R. Caroli’s disease: evaluation with MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Abdom Imaging. 1996;21:117-119. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Krausé D, Cercueil JP, Dranssart M, Cognet F, Piard F, Hillon P. MRI for evaluating congenital bile duct abnormalities. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:541-552. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Park DH, Kim MH, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim KP, Han JM, Kim SY, Song MH, Seo DW, Kim AY. Accuracy of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for locating hepatolithiasis and detecting accompanying biliary strictures. Endoscopy. 2004;36:987-992. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 70. | Park DH, Kim MH, Lee SK, Lee SS, Choi JS, Lee YS, Seo DW, Won HJ, Kim MY. Can MRCP replace the diagnostic role of ERCP for patients with choledochal cysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:360-366. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Wu KL, Changchien CS, Kuo CM, Chuah SK, Chiu YC, Kuo CH. Caroli’s disease - a report of two siblings. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1397-1399. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Caroli-Bosc FX, Demarquay JF, Conio M, Peten EP, Buckley MJ, Paolini O, Armengol-Miro JR, Delmont JP, Dumas R. The role of therapeutic endoscopy associated with extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy and bile acid treatment in the management of Caroli’s disease. Endoscopy. 1998;30:559-563. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Yilmaz S, Kirimlioglu H, Kirimlioglu V, Isik B, Coban S, Yildirim B, Ara C, Sogutlu G, Yilmaz M. Partial hepatectomy is curative for the localized type of Caroli’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Surgeon. 2006;4:101-105. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Guy F, Cognet F, Dranssart M, Cercueil JP, Conciatori L, Krausé D. Caroli’s disease: magnetic resonance imaging features. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2730-2736. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 75. | Kassahun WT, Kahn T, Wittekind C, Mössner J, Caca K, Hauss J, Lamesch P. Caroli’s disease: liver resection and liver transplantation. Experience in 33 patients. Surgery. 2005;138:888-898. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | De Kerckhove L, De Meyer M, Verbaandert C, Mourad M, Sokal E, Goffette P, Geubel A, Karam V, Adam R, Lerut J. The place of liver transplantation in Caroli’s disease and syndrome. Transpl Int. 2006;19:381-388. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Kim K, Choi J, Park Y, Lee W, Kim B. Biliary cystadenoma of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:348-352. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 78. | Díaz de Liaño A, Olivera E, Artieda C, Yárnoz C, Ortiz H. Intrahepatic mucinous biliary cystadenoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:678-680. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Mitchell P, McKinnon G, Nayak V. Cystadenomas of the liver: a spectrum of disease. Can J Surg. 2001;44:371-376. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 80. | Delis SG, Touloumis Z, Bakoyiannis A, Tassopoulos N, Paraskeva K, Athanassiou K, Safioleas M, Dervenis C. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: a need for radical resection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:10-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Lewin M, Mourra N, Honigman I, Fléjou JF, Parc R, Arrivé L, Tubiana JM. Assessment of MRI and MRCP in diagnosis of biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:407-413. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Thomas JA, Scriven MW, Puntis MC, Jasani B, Williams GT. Elevated serum CA 19-9 levels in hepatobiliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma. Two case reports with immunohistochemical confirmation. Cancer. 1992;70:1841-1846. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 83. | Thomas KT, Welch D, Trueblood A, Sulur P, Wise P, Gorden DL, Chari RS, Wright JK, Washington K, Pinson CW. Effective treatment of biliary cystadenoma. Ann Surg. 2005;241:769-73; discussion 773-775. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Vogt DP, Henderson JM, Chmielewski E. Cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the liver: a single center experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:727-733. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Koffron A, Rao S, Ferrario M, Abecassis M. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: role of cyst fluid analysis and surgical management in the laparoscopic era. Surgery. 2004;136:926-936. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 86. | Gadzijev E, Ferlan-Marolt V, Grkman J. Hepatobiliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinoma. Report of five cases. HPB Surg. 1996;9:83-92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. A light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:1078-1091. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 325] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Läuffer JM, Baer HU, Maurer CA, Stoupis C, Zimmerman A, Büchler MW. Biliary cystadenocarcinoma of the liver: the need for complete resection. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1845-1851. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Teoh AY, Ng SS, Lee KF, Lai PB. Biliary cystadenoma and other complicated cystic lesions of the liver: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World J Surg. 2006;30:1560-1566. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Taouli B, Koh DM. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the liver. Radiology. 2010;254:47-66. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 623] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 594] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 91. | Yamada I, Aung W, Himeno Y, Nakagawa T, Shibuya H. Diffusion coefficients in abdominal organs and hepatic lesions: evaluation with intravoxel incoherent motion echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;210:617-623. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 92. | Hadjis NS, Blenkharn JI, Alexander N, Benjamin IS, Blumgart LH. Outcome of radical surgery in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 1990;107:597-604. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 93. | Regev A, Reddy KR, Berho M, Sleeman D, Levi JU, Livingstone AS, Levi D, Ali U, Molina EG, Schiff ER. Large cystic lesions of the liver in adults: a 15-year experience in a tertiary center. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:36-45. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 94. | Castelletto RH, Cobas C, Mainetti LM, Aramburu C. Pseudosarcomatous cystadenocarcinoma versus biliary carcinosarcoma of the liver. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:1363-1364. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Balzan S, Kianmanesh R, Farges O, Sauvanet A, O’toole D, Levy P, Ruszniewski P, Ogata S, Belghiti J. Right intrahepatic pseudocyst following acute pancreatitis: an unusual location after acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:135-137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Motoo Y, Yamaguchi Y, Watanabe H, Okai T, Sawabu N. Hepatic peribiliary cysts diagnosed by magnetic resonance cholangiography. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:271-275. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 97. | Horii T, Ohta M, Mori T, Sakai M, Hori N, Yamaguchi K, Fujino H, Oishi T, Inada Y, Nakamura K. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst. A report of one case and a review of the literature. Hepatol Res. 2003;26:243-248. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 98. | Sharma S, Dean AG, Corn A, Kohli V, Wright HI, Sebastian A, Jabbour N. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst: an increasingly diagnosed condition. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:581-589. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 99. | Guérin F, Hadhri R, Fabre M, Pariente D, Fouquet V, Martelli H, Gauthier F, Branchereau S. Prenatal and postnatal Ciliated Hepatic Foregut Cysts in infants. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:E9-E14. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 100. | Wu ML, Abecassis MM, Rao MS. Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst mimicking neoplasm. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2212-2214. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 101. | Zheng RQ, Zhang B, Kudo M, Onda H, Inoue T. Imaging findings of biliary hamartomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6354-6359. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 102. | Lin S, Weng Z, Xu J, Wang MF, Zhu YY, Jiang JJ. A study of multiple biliary hamartomas based on 1697 liver biopsies. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:948-952. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |