Published online Jun 28, 2012. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i6.283

Revised: April 8, 2012

Accepted: April 15, 2012

Published online: June 28, 2012

The craniofacial region is a rare site for chondrosarcomas. These tumors may have osseous or extraosseous origin. Extraosseous chondrosarcomas have the same histological features as osseous chondrosarcomas. Chondrosarcomas usually present in the fifth to seventh decades of life, although several cases with younger age at presentation have been reported. They usually present as a painless mass that gradually progresses to various complaints, such visual impairment, nasal obstruction, and dental abnormalities. In this article, we present two cases of chondrosarcoma occurring at rather unusual locations. It is important to keep this rare malignancy in the list of differential diagnoses for a mass in the head and neck region, as these tumors may not always show the features typical of this malignancy.

- Citation: Gupta P, Bhalla AS, Karthikeyan V, Bhutia O. Two rare cases of craniofacial chondrosarcoma. World J Radiol 2012; 4(6): 283-285

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v4/i6/283.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v4.i6.283

Craniofacial chondrosarcomas are rare and may be osseous or extraosseous. They have the same age at onset as the typical chondrosarcoma, although young patient presentation is not unusual. They are usually symptomatic and the symptoms refer to the mass effect of the tumor and hence are varied. The most common sites of involvement are petroclival, spheno-occipital, and frontonasal synchondroses. Radiological diagnosis can be straightforward for lesions showing typical calcifications, however, tumors with atypical imaging appearances are not at all uncommon. It is important to keep this entity in the list of differential diagnoses for head and neck masses. Complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice.

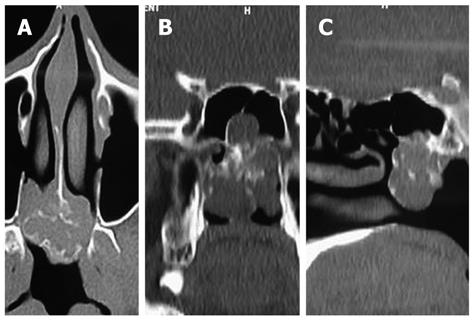

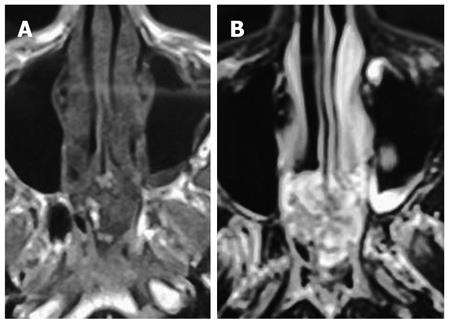

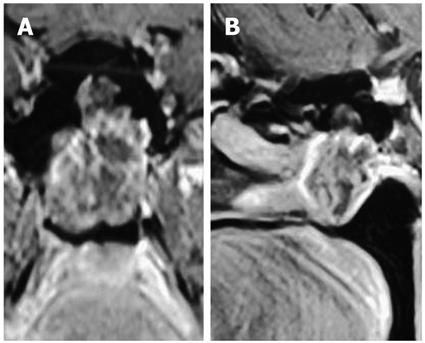

A 38-year-old male presented to the outpatient department with complaints of progressive nasal obstruction and sub-occipital headache for the past 2 years. Anterior rhinoscopy was unrevealing. A non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) scan of the paranasal sinuses (PNS) was advised with a clinical suspicion of chronic sinusitis. Axial images (Figure 1A) with coronal and sagittal reformations (Figure 1B and C) of NCCT PNS revealed a lesion arising from the floor of the sphenoid sinus with a soft tissue component and causing bone destruction. There was pleomorphic calcification within the mass not typical of the chondroid matrix. The lesion showed extension to the posterior choanae. Based on the CT appearance, differential diagnoses of plasmacytoma, giant cell tumor, metastasis and chondrosarcoma were made. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed with the intention of narrowing the differential diagnoses. Axial T1 and T2-weighted images (Figure 2A and B) revealed a lobulated soft tissue mass measuring 5 cm × 4 cm arising from the floor of the sphenoid sinus and extending to the posterior choanae. The lesion was T1 isointense and T2 hyperintense with hypointense areas within. Coronal and sagittal images after administration of gadolinium (Figure 3A and B) showed peripheral enhancement. Nasal endoscopy was carried out and a biopsy specimen obtained. Chondrosarcoma was reported on histopathology.

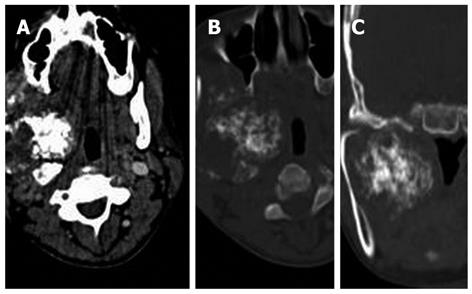

A 25-year-old female presented with fullness in the right cheek with difficulty in chewing. On examination a bulge was noted in the right masseteric region which felt bony hard on palpation. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of the neck was advised to identify the origin, extent and nature of the mass. CECT of the neck in axial soft tissue and bone window settings (Figure 4A and B) and coronal reformatting in the bone window setting (Figure 4C) showed a large soft tissue mass in the right parapharyngeal and masseteric space with scalloping of the inner cortex of the condyle and body of the mandible. The most distinctive feature of the mass was a chondroid pattern of calcification which involved almost the entire mass. Percutaneous biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathology revealed a low-grade chondrosarcoma. The mass was excised.

Craniofacial chondrosarcomas are rare tumors accounting for less than 10% of malignancies in the head and neck region[1]. Chondrosarcomas more commonly involve the long bones, pelvis, and ribs. Craniofacial chondrosarcomas may arise from bone, cartilage, or soft-tissue structures, but have a predilection for the skull base which is related to their origin from the cartilaginous remnants of the petroclival, spheno-occipital, and frontonasal synchondroses[2,3]. However, they may arise from tissues that do not normally harbor cartilage. This represents the pluripotent differentiation of primitive mesenchymal cells[4]. They most commonly involve the mandible, maxilla, or cervical vertebrae[5]. Sinonasal chondrosarcomas account for a good number of cases of head and neck chondrosarcomas. Chondrosarcomas are slow-growing invasive tumors, and are usually high-grade[6].

Patients with sinonasal chondrosarcoma may present with chronic nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, epistaxis, headaches or proptosis. The diagnosis of head and neck chondrosarcomas is based on imaging and histopathology. Diagnosis on CT is based on the typical chondroid pattern of calcification. Chondrosarcomas are typically hypo- to isointense on T1-weighted MR images and markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted MR images. The T2 hyperintensity is related to the high water content of hyaline cartilage. They show a characteristic curvilinear septal enhancement on MR images which corresponds to fibrovascular bundles surrounding the cartilaginous nodules[7]. This septal enhancement pattern is helpful in the identification of low-grade chondrosarcoma. With high-grade lesions, this characteristic MR appearance is not seen. In addition, there is a relationship between the density of calcification in chondrosarcoma and the grade of malignancy. High-grade malignancies contain large areas of non-calcified tumor[8]. Another tumor of osseous origin found in the head and neck is osteosarcoma. The radiological differentiation between the two tumors can be challenging. In general, chondrosarcomas are less aggressive with erosion as the predominant behavior rather than frank destruction. Matrix mineralization is helpful when it is definitely osteoid, however, tumors may not be calcified or the matrix can show chondroid differentiation. Complete surgical excision is the only curative treatment for craniofacial chondrosarcoma. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are not effective in these tumors.

In conclusion, chondrosarcomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of head and neck masses with or without the typical calcification pattern.

Peer reviewer: Yasunori Minami, MD, PhD, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, 377-2 Ohno-higashi Osaka-sayama, Osaka 589-8511, Japan

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Gadwal SR, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gannon FH, Thompson LD. Primary chondrosarcoma of the head and neck in pediatric patients: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases with a review of the literature. Cancer. 2000;88:2181-2188. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Rosenberg AE, Nielsen GP, Keel SB, Renard LG, Fitzek MM, Munzenrider JE, Liebsch NJ. Chondrosarcoma of the base of the skull: a clinicopathologic study of 200 cases with emphasis on its distinction from chordoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1370-1378. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Rapidis AD, Archondakis G, Anteriotis D, Skouteris CA. Chondrosarcomas of the skull base: review of the literature and report of two cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1997;25:322-327. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kumar AJ, Lee YY, Zinreich J, Leeds NE. Imaging features of skull base tumors. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 1993;3:715-734. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Rassekh CH, Nuss DW, Kapadia SB, Curtin HD, Weissman JL, Janecka IP. Chondrosarcoma of the nasal septum: skull base imaging and clinicopathologic correlation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;115:29-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamamoto S, Motoori K, Takano H, Nagata H, Ueda T, Osaka I. Chondrosarcoma of the nasal septum. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31:543-546. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Murphey MD, Walker EA, Wilson AJ, Kransdorf MJ, Temple HT, Gannon FH. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of primary chondrosarcoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:1245-1278. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |