Published online Aug 10, 2012. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v3.i8.116

Revised: June 14, 2012

Accepted: August 2, 2012

Published online: August 10, 2012

AIM: To describe clinical characteristics of head and neck cancer (HNC) patients with pain and those wishing to discuss pain concerns during consultation.

METHODS: Cross-sectional, questionnaire study using University of Washington Quality of Life, version 4 (UW-QOL) and the Patients Concerns Inventory (PCI) in disease-free, post-treatment HNC cohort. Significant pain on UW-QOL and indicating “Pain in head and neck” and “Pain elsewhere” on PCI.

RESULTS: One hundred and seventy-seven patients completed UW-QOL and PCI. The prevalence of self-reported pain issues was 38% (67/177) comprising 25% (44/177) with significant problems despite medications and 13% (23/177) with lesser or no problems but wishing to discuss pain. Patients aged under 65 years and patients having treatment involving radiotherapy were more likely to have pain issues. Just over half, 55% (24/44) of patients with significant pain did not express a need to discuss this. Those with significant pain or others wanting to discuss pain in clinic had greater problems in physical and social-emotional functioning, reported suboptimal QOL, and also had more additional PCI items to discuss in clinic compared to those without significant pain and not wishing to discuss pain.

CONCLUSION: Significant HNC-related pain is prevalent in the disease-free, posttreatment cohort. Onward referral to a specialist pain team may be beneficial. The UW-QOL and PCI package is a valuable tool that may routinely screen for significant pain in outpatient clinics.

- Citation: Rogers SN, Cleator AJ, Lowe D, Ghazali N. Identifying pain-related concerns in routine follow-up clinics following oral and oropharyngeal cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2012; 3(8): 116-125

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v3/i8/116.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v3.i8.116

Pain can be experienced at various time points in the cancer journey of an individual with head and neck cancer (HNC)[1]. Cancer-related pain is due to the direct effect of the tumor and/or the consequence of HNC treatment. Non-cancer related pain can co-exist and may contribute to the overall pain experience[2,3]. Pain experienced by HNC patients may have a detrimental impact on their general well-being[4], cause dysfunction[5,6] and distress[7,8], is associated with poor sleep quality[9] and poor health-related quality of life[10], can mark the onset of malignant transformation[11] and recurrence[12], and reduces survival rate[13]. Although the impact of pain in HNC patients is significant, its management is difficult[14] and often inadequate[2]. There are several obstacles to optimal pain management in this group of patients. There is an incomplete understanding of the HNC-related pain experience, particularly in the post-diagnosis period[3]. Current approach to cancer-related pain management emphasizes heavily on the pharmacological approach based on the World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder[1,15] with less consideration on the psycho-cognitive aspects underlying pain and how this influences coping[16]. Involvement of the pain specialist in HNC cases may be limited in many HNC set-ups[2,5]. There may be an inadequate appreciation by non-pain specialist practitioners of the neuropathic mechanisms involved in HNC-related pain[17] with consequential bearing on symptom management[2]. Health professionals’ reluctance towards opioid use[3] and patients reservations due to fear of addiction[16] may hinder adequate pain control, especially for breakthrough pain, which is common among HNC patients[2,18]. Finally, HNC patients may have difficulty self-reporting pain to their medical care providers[19] and routine screening may assist them in conveying this issue to the clinician.

Opportunistic evaluation of pain in HNC patients is achievable by using Health Related Quality Of Life tools. Pain is frequently assessed as part of HNC patient-reported outcomes using various health-related quality of life tools[3], including the University of Washington Quality of Life version 4 questionnaire (UW-QOL)[20]. When the UW-QOL is used in routine oncology clinical practice, this tool may offer a platform to identify those with significant problems in any of the 12 domains assessed (including pain) and also provides a trigger mechanism for supportive intervention[21]. The UW-QOL trigger for supportive intervention is based on defined cut-off points in the response scores of each domain, beyond which patients would be expected to encounter significant dysfunction/problems. This method correlated well with validated head and neck specific questionnaires e.g., Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS-24) and the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory, in identifying those with significant issues with appearance and swallowing respectively[21]. However, in regard to the pain domain, the cut-off point for supportive intervention was not correlated with any pain-specific questionnaire due to the lack of a suitable HNC pain-specific questionnaire that considers the complexity of HNC-related pain. The complexity of HNC-related pain is due to in part, the influence of multiple sources of somatic tissue and neural damage resulting from cancer and/or its treatment, and also from the personal and subjective nature of the pain experienced, which may be influenced by cultural learning, the meaning of the situation, attention, and other psychologic variables[22].

The Patients Concerns Inventory (PCI) is a 55-item checklist tool introduced to assist HNC patients in highlighting the items of concern that they may wish to discuss with clinicians during routine oncology consultations[23]. In the PCI item checklist, pain is covered in 2 items: “Pain in the head and neck” and “Pain elsewhere”. The original PCI study found that the “Pain in the head and neck” and “Pain elsewhere” were indicated as items of concern in 20% (4th most common item) and 10% (15th most common item) respectively[23]. As there is no limit to the number of PCI items that patients could choose from, patients may also indicate other items they perceive to be of concern and wish to be addressed during consultation. This includes other items that may be associated with or influence pain, such as fear of recurrence, anxiety, swallowing, saliva and shoulder[10,12,16,24]. We have found that the PCI is a valuable tool in understanding a wider scope of issues that HNC patients may experience in the post-treatment period based on previous work[25-29] and facilitates patient-clinical discussion regarding these issues and the need for supportive care.

There is a paucity of work relating specifically to the pain experience of HNC patients who have undergone treatment[3]. The rationale for this work is to understand how post-treatment HNC patients with pain self-report their experience using the PCI in a routine clinic outpatient setting, which forms part of the on going work of this unit with the PCI. The aims of this paper are: First, to report the clinical characteristics of HNC patients with pain attending routine outpatients and those wishing to discuss the issue of pain in their consultation and second, to identify if the issue of pain was mentioned in the clinic letter and if onward referral was made.

Prospective data collection from HNC patients attending routine follow-up clinics occurred from October 2008 to January 2011. Patients on the Liverpool oncology database were included if they were disease-free and under routine follow-up at least 6 wk after completing treatment. Patients were excluded if they were pretreatment, palliative, attending the clinic for other post-operative wound management or were part of another outcomes study in clinic.

Touch-screen technology (TST) was used by patients before their consultation to complete PCI, a holistic, self-reported screening tool for unmet needs/concerns and UW-QOL, version 4[30]. Following registration to clinic, patients were invited by a hospital volunteer to complete the TST questionnaire package. TST data was collected using Microsoft Access and placed directly on to a secure hospital server and was accessible to the clinician immediately before the consultation. The PCI measure asked patients to indicate which of 55 issues they would like to discuss during their consultation, and two of these issues involved pain – pain in the head and neck and pain elsewhere. Patients were also asked to select members of staff, from a list of 14 types of health professional, who they would “like to see or be referred to”.

The UW-QOL questionnaire is well established[31]. For this study the UW-QOL was analysed in terms of its two subscale composite scores, “physical function” and “social-emotional function”[32] as well as its domains and a single six-point Likert scale “overall” QOL measure. Physical function is the simple average of the swallowing, chewing, speech, saliva, taste and appearance domain scores whilst social-emotional function is the simple average of the activity, recreation, pain, mood, anxiety and shoulder domain scores. The pain domain is scored on a five point Likert scale as: (100) I have no pain, (75) There is mild pain not needing medication, (50) I have moderate pain – requires medication (e.g., paracetamol), (25) I have severe pain controlled only by prescription medicine (e.g., morphine), (0) I have severe pain, not controlled by medication. In earlier work[21] we defined a “significant problem” with pain as being a UW-QOL domain score of (0) or (25) or also as (50) if pain had been one of the three most important domains to the patient over the previous week. We also refer to earlier work[33] to provide normative reference scores for pain. In regard to the single item overall QOL scale, patients were asked to consider not only physical and mental health, but also other factors, such as family, friends, spirituality or personal leisure activities important to their enjoyment of life.

Details of onward referrals regarding pain arising subsequently from consultations were obtained from clinic letters. Clinical-demographic data came from the Liverpool HNC database.

Results were analysed mainly within three patient subgroups defined by reference to whether there was any evidence of significant pain from the UW-QOL and to whether pain issues were raised for discussion on the PCI. The χ2 test compared the patient subgroups with regard to categorical patient characteristics including the presence or absence of significant problems on each of the other domains of the UW-QOL. The Kruskal-Wallis test compared the subgroups in regard to age, months from primary treatment, UW-QOL overall QOL Likert scale, UW-QOL subscale scores for physical and social-emotional function, number of PCI concerns raised and number of staff members selected. As the UW-QOL and PCI TST package is integrated into routine clinical practice in this setting, this study was approved by the University Hospital Aintree Clinical Audit department in the context of service evaluation.

There were 396 TST sets of data that included both PCI and UW-QOL, from 177 patients during the course of 79 clinic sessions. Nearly two-thirds of patients (63%, 112/177) attended clinic more than once during the study, with 53 attending two, 29 attending three, 19 attending four and 11 attending five to seven times. Males comprised 63% (112) and the mean (SD) age at first clinic was 62 (12) years (range 24-86 years). Most patients (89%, 158) had a primary diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, with others including: low grade polymorphous adenocarcinoma (4), adenoid cystic carcinoma (2), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (2), and verrucous carcinoma (2). Most (71%, 126) had oral tumors, with 23% (41) pharyngeal and 6% (10) others. Overall, 19% (34) had advanced T3-T4 tumors and 20% (36) were clinically neck node positive. Just over half (58%, 103) had been treated by surgery alone, 32% (56) by surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy, and 10% (18) without surgery (by radiotherapy/chemotherapy). Overall 43% (76) had free-flap primary surgery with selective neck dissection. At first clinic 41% (73) were within 12 mo of diagnosis, 13% (23) within 12-23 mo, 21% (37) within 24-47 mo and 25% (44) after 48 mo.

Before the first study clinic consultation, 25% (44/177) of patients reported significant problems with pain (i.e., scores of 0 or 25 or 50 and important on the UW-QOL). This contrasts with significant problem levels of 13% (44/349) in data reanalysed for non-cancer patients routinely attending ten general dental practices and 100% (23/23) for non-cancer patients attending these practices in an emergency[33].

“Pain in the head and neck” was raised by patients on the PCI in 18% (32/177) of cases, and “Pain elsewhere” by 10% (17/177), with one or the other raised by 24% (43/177). A total of 38% (67/177) reported significant pain problems on the UW-QOL or highlighted issues of pain on the PCI for discussion (Table 1), with 25% (44/177) meeting the UW-QOL criteria while an extra 13% (23/177) met only the PCI criteria (more minor concerns they wanted to discuss). One-half (55%, 24/44) of those with a significant pain problem did not wish to discuss it. Subsequent analyses focus on three groups for comparison: the 62% (110) of patients without significant pain and with no wish to discuss pain (Group A), the 25% (44) with significant pain (Group B), and the 13% (23) without significant pain who wanted to discuss pain (Group C, 18 to discuss head and neck pain, 5 to discuss pain elsewhere).

| UW-QOL Pain | Stated on PCI that patient wished to discuss the issue of “Pain in head and neck” | |||

| No (Stated on PCI that patient wished to discuss the issue of “Pain elsewhere”) | Yes (Stated on PCI that patient wished to discuss the issue of “Pain elsewhere”) | |||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| (0) I have severe pain, not controlled by medication | 32 | -2 | -2 | 22 |

| (25) I have severe pain controlled only by prescription medicine (e.g., morphine) | 112 | 32 | 22 | 12 |

| (50) I have moderate pain - requires medication (e.g., paracetamol)/and pain IMPORTANT1 | 102 | 32 | 62 | 32 |

| (50) I have moderate pain - requires medication (e.g., paracetamol)/and pain NOT IMPORTANT1 | 13 | 22 | 32 | -2 |

| (75) There is mild pain not needing medication | 22 | 32 | 82 | -2 |

| (100) I have no pain | 75 | -2 | 72 | -2 |

Patients aged 65 years and older reported less significant pain and fewer wished to discuss pain than younger patients (Table 2). Patients having primary treatment without surgery reported higher levels of significant pain. Significant problems in physical functioning were reported more often by patients with significant pain (Table 3). Both Group B and C reported more problems relating to social and emotional function and to overall QOL than Group A. In particular, half of Group B and C patients had significant problems with mood and/or anxiety in contrast to 14% of Group A. Similarly, overall QOL was less than good for half of Group B and C patients compared to 18% for Group A.

| Patients | No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain (n = 110) | Significant pain (n = 44) | No significant pain but wish to discuss pain (n = 23) | P value1 | |

| Male | 112 | 71 (63) | 29 (26) | 12 (11) | 0.49 |

| Female | 65 | 39 (60) | 15 (23) | 11 (17) | |

| Age (< 55 yr) | 45 | 23 (51) | 15 (33) | 7 (16) | 0.03 |

| Age (55-64 yr) | 64 | 35 (55) | 19 (30) | 10 (16) | |

| Age (65+ yr) | 68 | 52 (76) | 10 (15) | 6 (9) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 158 | 101 (64) | 39 (25) | 18 (11) | 0.16 |

| Other diagnosis | 19 | 9 (47) | 5 (25) | 5 (26) | |

| Oral cavity tumor | 126 | 83 (66) | 28 (22) | 15 (12) | 0.71 (oral vs pharyngeal) |

| Pharygeal | 41 | 20 (49) | 15 (37) | 6 (15) | |

| Other site | 10 | 7 (70) | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | |

| Clinical T1/T2 | 140 | 93 (66) | 31 (22) | 16 (11) | 0.11 |

| Clinical T3/T4 | 34 | 16 (47) | 12 (35) | 6 (12) | |

| Clinical N0 | 139 | 89 (64) | 34 (24) | 16 (12) | 0.43 |

| Clinical N+ | 36 | 20 (56) | 9 (25) | 7 (19) | |

| Primary surgery only | 103 | 68 (66) | 26 (25) | 9 (9) | 0.006 |

| Primary surgery and RT | 56 | 32 (57) | 10 (18) | 14 (25) | |

| No surgery, primary RT | 18 | 10 (56) | 8 (44) | - (-) | |

| Within 12 months of diagnosis | 73 | 45 (62) | 20 (27) | 8 (11) | 0.18 |

| Within 12-23 mo of diagnosis | 23 | 15 (65) | 6 (26) | 2 (9) | |

| Within 24-47 mo since diagnosis | 37 | 23 (62) | 10 (27) | 4 (11) | |

| 48 or more months from diagnosis | 44 | 27 (61) | 8 (18) | 9 (20) |

| No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain (n = 110) | Significant pain(n = 44) | No significant pain but wish to discuss pain (n = 23) | P value2 | |

| Significant problems3 | ||||

| Appearance | 5 (5) | 14 (32) | 2 (9) | < 0.001 |

| Swallowing | 17 (15) | 14 (32) | 3 (13) | 0.05 |

| Chewing | 15 (14) | 9 (20) | 1 (4) | 0.19 |

| Speech | 5 (5) | 7 (16) | - (-) | 0.02 |

| Taste | 15 (14) | 7 (16) | - (-) | 0.14 |

| Saliva | 17 (15) | 12 (27) | 7 (30) | 0.04 |

| Physical function subscale, median (IQR) | 80 (62-95) | 58 (45-72) | 68 (54-72) | < 0.001 |

| Significant problems3 | ||||

| Activity | 7 (6) | 8 (18) | 4 (17) | 0.06 |

| Recreation | 7 (6) | 4 (9) | 3 (13) | 0.53 |

| Shoulder | 6 (5) | 7 (16) | 7 (30) | 0.001 |

| Mood | 10 (9) | 21 (48) | 6 (26) | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 11 (10) | 18 (41) | 7 (30) | < 0.001 |

| Mood and/or anxiety | 15 (14) | 23 (52) | 11 (48) | < 0.001 |

| Social-emotional subscale1, median (IQR) | 85 (73-94) | 60 (45-73) | 63 (54-79) | < 0.001 |

| Overall QOL | ||||

| Very poor | - (-) | - (-) | - (-) | < 0.001 |

| Poor | 4 (4) | 6 (14) | 2 (9) | |

| Fair | 16 (15) | 17 (40) | 9 (41) | |

| Good | 32 (29) | 13 (30) | 6 (27) | |

| Very good | 44 (40) | 6 (14) | 5 (23) | |

| Outstanding | 14 (13) | 1 (2) | - (-) | |

| % less than good | 20 (18) | 23 (53) | 11 (50) | < 0.001 |

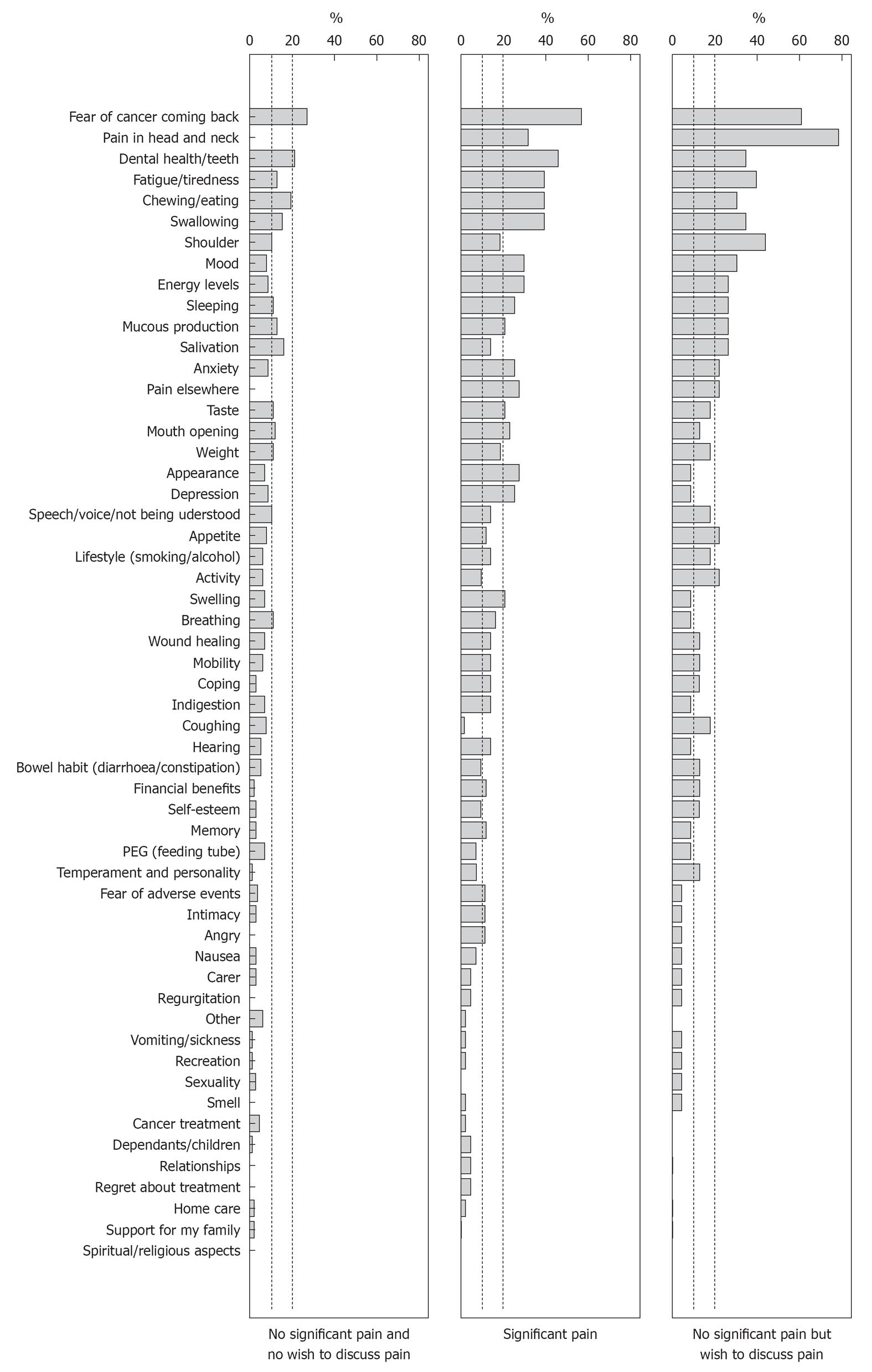

In regard to PCI concerns, Figure 1 indicates that Group B and C raised considerably more issues to discuss than Group A. The median [interquartile range (IQR)] total number of concerns per patient were 7 (4-12), 7 (5-10) and 2 (1-5) respectively, P < 0.001. In total there were 940 issues raised by the 177 patients (Table 4): the 23% of all patients that form Group B raised 39% (369) of all issues, whilst the 13% in Group C raised 21% (195) of issues and the 62% in Group A raised 40% (376) of issues.

| No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain (n = 110) | Significant pain (n = 44) | No significant pain but wish to discuss pain (n = 23) | |||

| Issue | % | Issue | % | Issue | % |

| Fear of the cancer coming back | 26 | Fear of the cancer coming back | 57 | Pain in head and neck | 78 |

| Dental health/teeth | 21 | Dental health / teeth | 46 | Fear of the cancer coming back | 61 |

| Chewing /Eating | 21 | Chewing / Eating | 39 | Shoulder | 44 |

| Salivation | 16 | Fatigue / tiredness | 39 | Fatigue / tiredness | 39 |

| Swallowing | 15 | Swallowing | 39 | Dental health / teeth | 35 |

| Mucous production | 13 | Pain in head and neck | 32 | Swallowing | 35 |

| Fatigue/tiredness | 13 | Mood | 30 | Chewing / Eating | 30 |

| Mouth opening | 12 | Energy levels | 30 | Mood | 30 |

| Breathing | 11 | Pain elsewhere | 27 | Mucous production | 26 |

| Sleeping | 11 | Appearance | 27 | Sleeping | 26 |

| Weight | 11 | Depression | 25 | Salivation | 26 |

| Taste | 11 | Sleeping | 25 | Energy levels | 26 |

| Anxiety | 25 | ||||

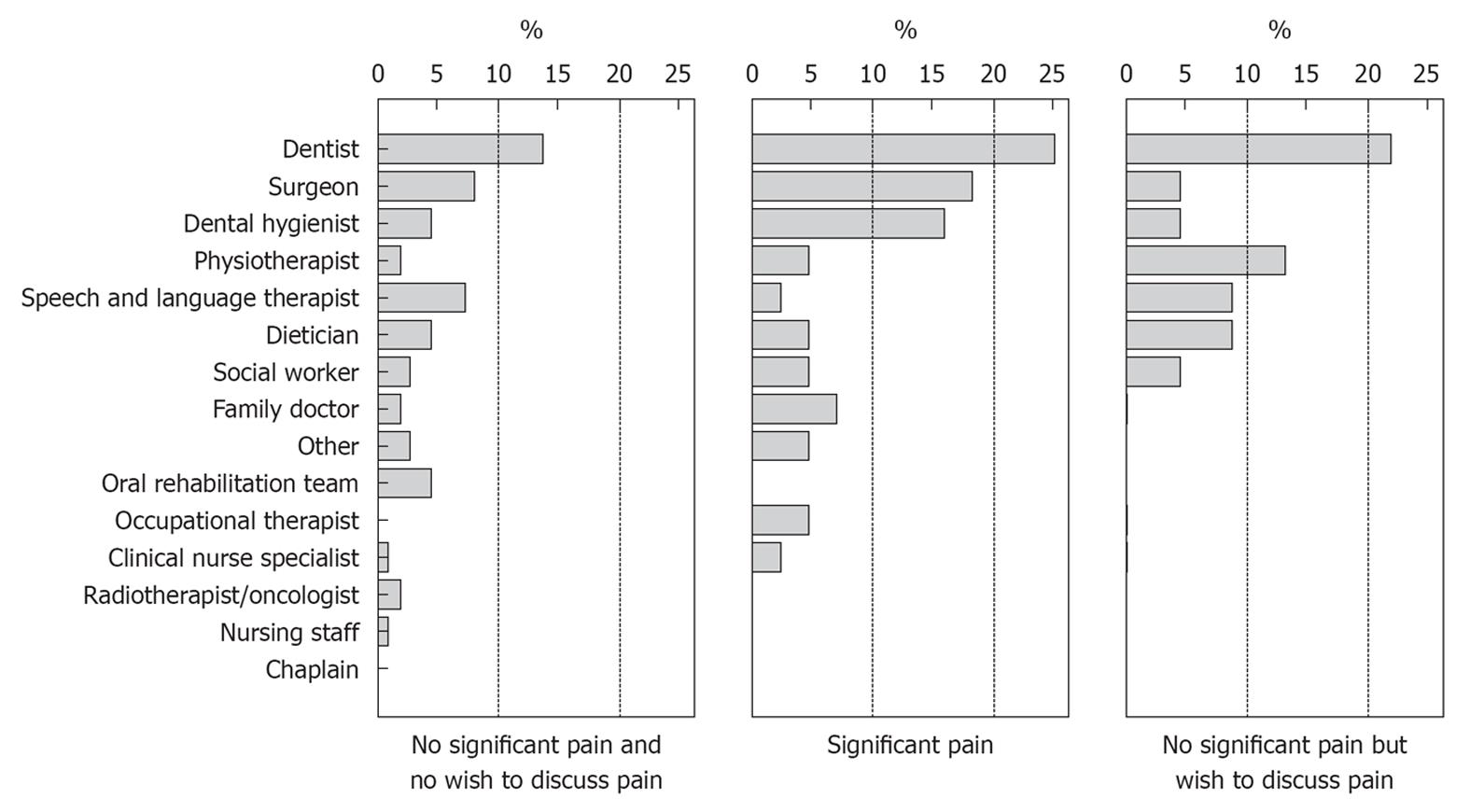

There were no notable differences between groups in terms of selected members of staff (Figure 2) apart from Group B who more often wanted to see or be referred on to dental services. The median (IQR) total number selected per patient were 0 (0-1), 1 (0-1) and 0 (0-1) respectively, P = 0.07. For patients attending clinic more than once in the study, the median (IQR) time between first and second clinics was 4 (2-9) mo, 11 (5-15) mo between first and third and 13 (8-20) mo between first and fourth. The longitudinal perspective in following through the three clinical groups from first study clinic is shown in Table 5. Of those with significant pain at first clinic (Group B), 76% (16/21) reported significant pain at second clinic, 65% (9/14) at third clinic and 50% (2/4) at fourth clinic. Those no longer having significant pain did not wish to discuss it at subsequent clinics. Also, of the 12 patients reporting significant pain in their third study clinic 67% (8) had also reported significant pain at their first and second clinics. Of those with no significant pain and not wishing to discuss it at the first study clinic (Group A) about three-quarters (78%, 79% and 83% respectively in successive clinics) remained in the same group. There was greater variability noted in later clinics for those without significant pain but wanting to discuss pain at the first clinic (Group C).

| First study clinic | |||

| No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain | Significant pain | No significant pain but wish to discuss pain | |

| Second study clinic (112 patients) | |||

| No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain | 55 | 5 | 9 |

| Significant pain | 8 | 16 | 4 |

| No significant pain but wish to discuss pain | 7 | - | 8 |

| Third study clinic (59 patients) | |||

| No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain | 31 | 5 | 3 |

| Significant pain | 3 | 9 | - |

| No significant pain but wish to discuss pain | 5 | - | 3 |

| Fourth study clinic (30 patients) | |||

| No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain | 20 | 2 | - |

| Significant pain | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| No significant pain but wish to discuss pain | 1 | - | 1 |

Those in Group B and C had pain mentioned in about half of the clinic letters subsequent to the clinic (Table 6), in contrast to just 12% of clinic letters from patients in Group A. The rates of onward referral for pain were 11%, 8% and 0.8% of clinics respectively for groups B, C and A. Details from the clinic letters as to whom the patient was referred, the medications that were mentioned and the nature and location of the pain are given in Table 6.

| No significant pain and no wish to discuss pain | Significant pain | No significant pain but wish to discuss pain | |

| Number of clinics (number of patients) | 256 (110) | 85 (44) | 55 (23) |

| Number of clinics with clinic letters found | 240 | 79 | 51 |

| Pain mentioned in clinic letter | 12% (29/240) from 27 patients (26 patients once, 1 patient 3 times) | 56% (44/79) from 29 patients (19 patients once, 7 patients twice, 1 patient three times, 2 patients four times) | 47% (24/51) from 19 patients (14 patients once, 5 patients twice) |

| Onward referral for pain | 0.8% (2/240) | 11% (9/79) (1 patient once, 2 patients twice, 1 patient 4 times) | 8% (4/51) |

| Who was patient referred to | Consultant gastroenterologist (1) | Patient 1: first to consultant orthopaedic surgeon then three times to chronic pain team | Senior physiotherapist (2) |

| Consultant restorative dentist (1) | Patient 2: first to senior physiotherapist then to chronic pain management programme | Consultant in oral medicine (1) | |

| Patient 3: first to consultant orthopaedic surgeon then to palliative care | Consultant in pain relief (1) | ||

| Patient 4: to consultant in oral medicine | |||

| Pain medications mentioned in letter (often in combination) | Gabapentin (1), Oromorph (1), MST (1) | Aciclovir (1), Aspirin (1), Brufen (2), Codeine phosphate (1), Dicofenac (1), Fentanyl patch 25 (1), Gabapentin (7), Morphine patches (2), MST (1), Oromorph (6), Oxynorm (3), Oxycontin (2), Paracetamol (4),Solpadeine (1), Solpadol (1) | None mentioned |

| Pain as mentioned in letter (number of occasion) | Oral and teeth pain (7) | Single site: Jaw (7); Neck (5); Teeth (1); Face (2); Oral/throat (5); Chest (1); Shoulder (2); Hip (1) | Oral/throat pain (4) |

| Jaw pain (4) | Multiple sites: 10 | Generalised pain in treated area (2) | |

| Facial pain (3) | Related to function: 1 | Back pain (2) | |

| Shoulder pain (4) | Related to fear of cancer recurrence: 3 | Shoulder pain (2) | |

| Neck pain (2) | Related to fear of addition to analgesia: 1 | Neck (4) | |

| Ear pain (2) | Shoulder and neck pain (2) | ||

| Stomach pain (2) | Shoulder pain | ||

| Back pain (1) | Jaw pain (1) | ||

| Chest wall pain (1) |

This work surveyed self-reported pain in a HNC cohort using the UW-QOL and PCI TST in a routine clinic setting. The main strength of this study lies in the description of self-reported pain in a disease-free, post-treatment group through exclusion of active, residual or recurrent disease because this subgroup may present with a slightly different management approach. The estimated prevalence of self-reported pain issues in this group was 38%, of which 25% had significant pain. Patient who self-report significant pain or others wanting to discuss pain were more likely to have problems in both physical and social-emotional functioning, report suboptimal overall QOL and raise more items other than pain for discussion on the PCI. Those having treatment with radiotherapy/chemotherapy were more likely to report significant pain or wish to discuss pain. However, just over one-half of those reporting significant problems with pain did not wish to discuss this during their consultation.

There are several issues that may limit this study. Firstly, the sample size (n = 177) is relatively small and mainly of patients with oral cancer. A larger cohort could better elicit any other potential trends from the data. The database also lacks sufficient longitudinal data to comment confidently on the stability of pain and the successful management of those patients in significant pain. Following the cohort through future outpatient clinics would achieve this, but the problem of a small study sample would persist. Secondly, this study did not use any specialised self-reported pain questionnaire or clinical examination to qualify the pain experienced by the cohort. This may be relevant from a clinical management perspective. Finally, this study did not have a pre-diagnosis baseline of the pain experience, which has been shown to influence the post-treatment experience of pain[4].

There is a wide range of published prevalence rates (6%-100%) for self-reported pain in HNC patients due to variation in the methodology employed[2], namely, the time point of the HNC journey selected (e.g., prediagnosis or postdiagnosis; remission or recurrence/active disease), clinical setting surveyed (e.g., oncology outpatients or specialist pain clinics) and treatment received (e.g., unimodality or multimodality). The prevalence of self-reported pain in our cohort was 38% (54% of patients studied were within 24 mo from the completion of treatment). This is higher than that found by Chaplin and Morton[4], who reported prevalence of 25% and 26% at 12 and 24 mo respectively. The reason for our higher prevalence is unclear although oral and oropharyngeal cancer accounted for only 29% of their sample, which also showed treatment preponderance for radiotherapy.

We found that the clinical factors associated with pain issues were age and primary treatment modality, not seen in the New Zealand cohort[4]. Those aged 65 years and older reported less significant pain and fewer wished to discuss their pain compared to younger people. This may be due to the possibility that older adults experience lower levels of pain severity and interference from cancer-related pain compared with the younger age group[34]. However, the contrary was found in the Taiwanese group, where the older group reported more pain and this was attributed to lower pain endurance ability[6]. In our cohort, patients who received radiotherapy as their primary treatment reported greater levels of significant pain or wanted to discuss pain. Persistent pain after the completion of radiotherapy is commonly reported[8]. Normal radiotoxicity can result in mucositis, xerostomia, brachial plexopathy and osteoradionecrosis of varying degree, which may cause orofacial pain. Pain secondary to oral mucositis is frequently reported during treatment and the radiation-mediated tissue changes are progressive, suggesting the role of neuropathic mechanisms[8].

Our cohort was split into three groups to facilitate statistical analysis: A, B and C based on the presence of a significant pain problem and the expression of need to discuss the issue of perceived pain. Group A (n = 110) did not have significant pain and did not wish to discuss pain on the PCI. This group includes those with manageable levels of pain as well as those who are pain-free, all of whom perceive pain to be of no concern. Group B (n = 44) had significant pain and includes some (just over half) who did not wish to discuss this during consultation. This group may provide a challenge for clinicians because of the unresolved problem of symptom control, the association of pain with physical dysfunction, the increased likelihood of having problems in the social-emotional areas and that so many of this subgroup do not wish to discuss this in clinic. Group C (n = 23) had no significant pain but still wanted to discuss pain in the consultation, indicating that this group may benefit from non-pharmacological interventions for their pain, especially as they were also associated with problems in social-emotional functioning.

Our study found that Groups B and C raised significantly more issues on the PCI than those in Group A (Table 4), where the median number of complaints of patients in Groups B, C and A was 7, 7 and 2, respectively. Interestingly (Tables 3 and 4), Group B and C also seem to struggle with mood, anxiety and depression, far more so than those in Group A. Other studies also report that depression and anxiety contributed to the pain quality ratings in post-treatment HNC patients[6,16]. Fear of recurrence was a prevalent concern across all groups (Table 4) and this could represent the perception that pain precedes the return of cancer[12]. Groups B and C had pain mentioned in almost half of their cohort’s clinic letters compared to just 12% of clinic letters from Group A (Table 6). Despite this, only 11% of patients from Group B and 8% from Group C were referred onwards for further management of their pain. In Groups B and C, referrals made were to pain specialist professionals (5/12 referrals) and non-pain specialist professionals (7/12 referrals).

Based on the clinic letters, most pain locations were in the head, neck and shoulder region, which compares with another report[8]. A much smaller proportion was reported at distant sites, including donor site morbidity. Both descriptors of nociceptive and neuropathic pain were used in the clinics letters. However, conclusions regarding the possible mechanisms of pain in this cohort cannot be derived from this list because we are unable to verify if these were the actual terms used by patients in clinic. Nevertheless, the list of medications described in clinic letters used for analgesia in Group B indicates that the range of medication on the WHO pain ladder[15] have been used, including adjunctive drugs for significant pain.

This may support for a more prominent role for the specialist pain team in the multidisciplinary team management of these patients.

In conclusion, pain remains a significant problem for those with HNC and can arise for many different reasons. Increased levels of pain tend to follow treatment that involves radiotherapy. Those with significant pain and others wanting to discuss pain tend to have multiple other areas of concern, including worries over depression and anxiety. Effective pain management is crucial to ensure a good quality of life and the role of the pain team in HNC is to be evaluated. The PCI approach to help patients highlight issues of concern during routine clinic review is potentially a useful way to help screen oncology patients for pain-related symptoms. Further modular development of the PCI concept in breast cancer and other cancer sites will allow this type of adjunct to be incorporated more widely in oncology.

Pain is prevalent among head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors. This may be the result of cancer-related pain and also other non-cancer related causes. Its management is complex and challenging due to the multidimensional nature of pain, particularly among the post-treatment, disease-free survivors. Under-reporting of pain by these patients can have damaging impact on their overall quality of life, as it is a source of suffering, distress and anxiety. It can be difficult to identify those who “suffer pain in silence” as some patients may not feel able to vocalize this issue and/or others for many reasons. There is currently no holistic screening tool that can be used in routine clinical practice to help identify HNC patients with concerns, particularly pain.

The Patients Concerns Inventory (PCI) is a holistic, patient-reported tool that enables patients to highlight items of concerns that they would like addressing during their outpatient visit. In addition, the PCI also allows patients to indicate professionals whom they would like access to. The PCI consists of a 57-item checklist that is administered along with the University of Washington Quality of Life (UW-QOL) using touch-screen computers prior to their consultation. The PCI promotes patient-centred consultations. By highlighting the PCI item “pain”, a focused discussion on their pain experience ensues during consultation. The UW-QOL data provides additional data in understanding the severity of their pain. The PCI-UW-QOL tool can potentially empower patients to take a bigger role in their care through self-care, participation in decision-making and by seeking access to specialist expertise for their pain problem.

Previous work on pain in HNC are heterogeneous in design and population characteristics. This study focused on post-treatment, disease-free patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Significant cancer-related pain is prevalent in this group, particularly those who were aged more than 65 years and had received radiotherapy. Patients who opted to discuss pain also indicated other issues of concern. This finding supports the notion of the multidimensional nature of pain. While onward referral to a specialist pain team may be beneficial, the other dimensions of the pain experience must be addressed. The PCI-UW-QOL package is a valuable tool that may routinely screen for significant pain in outpatient clinics.

The PCI is a holistic, multifunctional patient-reported tool. It can screen for patient concerns by providing a platform for expressing their needs. In addition, the PCI may be regarded as a communication tool to enhance patient-healthcare worker consultations/discussions. Although originally developed in HNC, the PCI concept may be applied to other cancers and also various non-cancer fields. Current developmental work is being carried out to apply the PCI in breast cancer, neuro-oncology, rheumatology and gastroenterology. In addition, expansion of the PCI into a web-based platform for health advice and direct access to healthcare services are being explored.

This is a well-written paper dealing with an important issue in the care of HNC patients. The study design is sound and the analysis is straightforward and clear.

Peer reviewers: Ho-Sheng Lin, MD, FACS, Associate Professor, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI 48201, United States; Alessandro Franchi, MD, Associate Professor, Division of Anatomic Pathology, Department of Critical Care Medicine and Surgery, Viale G. B. Morgagni 85, 50134, Florence, Italy

S- Editor Jiang L L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Dios PD, Lestón JS. Oral cancer pain. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:448-451. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Williams JE, Yen JT, Parker G, Chapman S, Kandikattu S, Barbachano Y. Prevalence of pain in head and neck cancer out-patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:767-773. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Epstein JB, Hong C, Logan RM, Barasch A, Gordon SM, Oberle-Edwards L, McGuire D, Napenas JJ, Elting LS, Spijkervet FK. A systematic review of orofacial pain in patients receiving cancer therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1023-1031. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Chaplin JM, Morton RP. A prospective, longitudinal study of pain in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 1999;21:531-537. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Chua KS, Reddy SK, Lee MC, Patt RB. Pain and loss of function in head and neck cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:193-202. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen SC, Liao CT, Chang JT. Orofacial pain and predictors in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients receiving treatment. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:131-135. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients 7-11 years after curative treatment. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:592-597. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 151] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Epstein JB, Wilkie DJ, Fischer DJ, Kim YO, Villines D. Neuropathic and nociceptive pain in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shuman AG, Duffy SA, Ronis DL, Garetz SL, McLean SA, Fowler KE, Terrell JE. Predictors of poor sleep quality among head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1166-1172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cheng KK, Leung SF, Liang RH, Tai JW, Yeung RM, Thompson DR. Severe oral mucositis associated with cancer therapy: impact on oral functional status and quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1477-1485. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lam DK, Schmidt BL. Orofacial pain onset predicts transition to head and neck cancer. Pain. 2011;152:1206-1209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Scharpf J, Karnell LH, Christensen AJ, Funk GF. The role of pain in head and neck cancer recurrence and survivorship. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:789-794. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sato J, Yamazaki Y, Satoh A, Onodera-Kyan M, Abe T, Satoh T, Notani K, Kitagawa Y. Pain may predict poor prognosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:587-592. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sist T, Wong C. Difficult problems and their solutions in patients with cancer pain of the head and neck areas. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:206-214. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief: with a guide to opioid availability. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization 1996; Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241544821.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Fischer DJ, Villines D, Kim YO, Epstein JB, Wilkie DJ. Anxiety, depression, and pain: differences by primary cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:801-810. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Potter J, Higginson IJ, Scadding JW, Quigley C. Identifying neuropathic pain in patients with head and neck cancer: use of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs Scale. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:379-383. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bhatnagar S, Upadhyay S, Mishra S. Prevalence and characteristics of breakthrough pain in patients with head and neck cancer: a cross-sectional study. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:291-295. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Moore RJ, Chamberlain RM, Khuri FR. A qualitative study of head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:338-346. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rogers SN, Gwanne S, Lowe D, Humphris G, Yueh B, Weymuller EA. The addition of mood and anxiety domains to the University of Washington quality of life scale. Head Neck. 2002;24:521-529. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 298] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rogers SN, Lowe D. Screening for dysfunction to promote multidisciplinary intervention by using the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:369-375. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Katz J, Melzack R. Measurement of pain. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:231-252. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 474] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rogers SN, El-Sheikha J, Lowe D. The development of a Patients Concerns Inventory (PCI) to help reveal patients concerns in the head and neck clinic. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:555-561. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 130] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McGarvey AC, Chiarelli PE, Osmotherly PG, Hoffman GR. Physiotherapy for accessory nerve shoulder dysfunction following neck dissection surgery: a literature review. Head Neck. 2011;33:274-280. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rogers SN, Scott B, Lowe D, Ozakinci G, Humphris GM. Fear of recurrence following head and neck cancer in the outpatient clinic. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:1943-1949. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ghazali N, Cadwallader E, Lowe D, Humphris G, Ozakinci G, Rogers SN. Fear of recurrence among head and neck cancer survivors: longitudinal trends. Psychooncology. 2012;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Flexen J, Ghazali N, Lowe D, Rogers SN. Identifying appearance-related concerns in routine follow-up clinics following treatment for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50:314-320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ghazali N, Kanatas A, Scott B, Lowe D, Zuydam A, Rogers SN. Use of the Patient Concerns Inventory to identify speech and swallowing concerns following treatment for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:800-808. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kanatas A, Ghazali N, Lowe D, Rogers SN. The identification of mood and anxiety concerns using the patients concerns inventory following head and neck cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:429-436. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Millsopp L, Frackleton S, Lowe D, Rogers SN. A feasibility study of computer-assisted health-related quality of life data collection in patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:761-764. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Laraway DC, Rogers SN. A structured review of journal articles reporting outcomes using the University of Washington Quality of Life Scale. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50:122-131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Rogers SN, Lowe D, Yueh B, Weymuller EA. The physical function and social-emotional function subscales of the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:352-357. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rogers SN, O'donnell JP, Williams-Hewitt S, Christensen JC, Lowe D. Health-related quality of life measured by the UW-QoL--reference values from a general dental practice. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:281-287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Soltow D, Given BA, Given CW. Relationship between age and symptoms of pain and fatigue in adults undergoing treatment for cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:296-303. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |