Published online Mar 22, 2015. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.147

Peer-review started: December 4, 2014

First decision: January 20, 2015

Revised: January 28, 2015

Accepted: February 10, 2015

Article in press: February 12, 2015

Published online: March 22, 2015

AIM: To compare outcomes in anorexia nervosa (AN) in different treatment settings: inpatient, partial hospitalization and outpatient.

METHODS: Completed and published in the English language, randomized controlled trials comparing treatment in two or more settings or comparing different lengths of inpatient stay, were identified by database searches using terms “anorexia nervosa” and “treatment” dated to July 2014. Trials were assessed for risk of bias and quality according to the Cochrane handbook by two authors (Madden S and Hay P) Data were extracted on trial quality, participant features and setting, main outcomes and attrition.

RESULTS: Five studies were identified, two comparing inpatient treatment to outpatient treatment, one study comparing different lengths of inpatient treatment, one comparing inpatient treatment to day patient treatment and one comparing day patient treatment with outpatient treatment. There was no difference in treatment outcomes between the different treatment settings and different lengths of inpatient treatment. Both outpatient treatment and day patient treatment were significantly cheaper than inpatient treatment. Brief inpatient treatment followed by evidence based outpatient care was also cheaper than prolonged inpatient care for weight normalization also followed by evidence based outpatient care.

CONCLUSION: There is preliminary support for AN treatment in less restrictive settings but more research is needed to identify the optimum treatment setting for anorexia nervosa.

Core tip: Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious disorder incurring high costs due to hospitalization. This study compared outcomes in AN treatment studies comparing different treatment settings: inpatient, day-patient and outpatient. Five studies were identified. There was no difference in outcomes between the different settings and lengths of inpatient treatment. Both outpatient and day-patient treatment were significantly cheaper than inpatient treatment. Brief inpatient treatment followed by evidence based outpatient care was cheaper than prolonged inpatient care for weight normalization. There is support for AN treatment in less restrictive settings but more research is needed to identify the optimum treatment setting.

- Citation: Madden S, Hay P, Touyz S. Systematic review of evidence for different treatment settings in anorexia nervosa. World J Psychiatr 2015; 5(1): 147-153

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v5/i1/147.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.147

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is characterized by the restriction of energy intake relative to requirements leading to a significantly low weight for gender, age, developmental trajectory and height. Individuals with AN maintain an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming overweight even though they are underweight. They have a disturbance in the way in which they perceive their body weight and shape, there is undue influence of weight and shape on self evaluation and/or they deny the seriousness of their illness[1].

Lifetime prevalence rates for AN range from 0.9%-2.3% with its onset primarily in adolescence[2-5]. AN is the third most common chronic disorder affecting adolescent females, with and average mortality rate of 5%, up to 18 times greater than in non-affected women aged 15-24 years[6]. The course of the illness is often protracted with less than 50% of individuals with AN achieving full recovery in a period of seven years after the onset of their illness[7]. Physical complications include growth retardation, osteoporosis, infertility and changes in brain structure[8], while psychological complications include depression, anxiety disorders including obsessive compulsive disorder and cognitive impairment[9-11].

While the complications of AN have been well documented, there is limited evidence to guide as to what is the most appropriate treatment setting. Current expert consensus and guidelines[12,13] support outpatient care as the first line treatment in AN and there is a growing body of evidence to guide such care, particularly the role of family treatment in adolescents[14]. There are, however, few studies comparing different treatment settings in AN and few studies into the role of inpatient treatment in AN. Hospitalization of patients with AN for the management of acute medical instability (e.g., hypothermia, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities and cardiac arrhythmias) is thought to be essential in preventing mortality associated with AN[8,15], however, the benefits of inpatient weight restoration and the assumption that hospital is the best venue for refeeding once medical stability has been achieved remain unsupported by current evidence[16]. This problem is highlighted by a recent meta-analysis of 57 clinical trials in AN that found no difference in treatment effects based on the style of therapy or treatment setting[17].

Treatment settings for AN include inpatient, partial hospitalization (also known as day hospital care) and outpatient. Inpatient treatment programs are usually multidisciplinary and treatment focuses on weight restoration, normalizing eating behavior and facilitating psychological change through nutritional education, supervised meals and individual and group psychotherapy[18,19]. In published trials admissions have been prolonged with a length of stay ranging from several months to 15.2 wk[22-24]. Partial hospitalization or day programs are similar to inpatient treatment in terms of a multidisciplinary approach, treatments offered and intensity and duration of treatment but with no overnight stays[22]. They are potentially more flexible and thus amenable to matching the individual level of motivation for change with goals of treatment[24]. Outpatient treatment generally involves once or twice a week sessions with a therapist of a single discipline and may be either individual or family based[12,13,25]. Outpatient treatments provide care in the least restrictive setting and thus are favored by current psychiatric practice[12,13].

The present article aims to assess the effects of different treatment settings including inpatient, partial hospitalization and outpatient on treatment outcomes in AN and to assess the effects of continuing hospitalization for weight normalization compared with brief hospitalization for medical stabilization in AN. Primary outcome measures included measures of clinical improvement including weight as measured by body mass index (BMI) in adults or percentage expected body weight in children and adolescents (%EBW) and changes in eating disorder psychopathology.

For the purposes of the present review the authors (Madden S and Hay P) sourced trials identified in previous broad searches conducted for treatment guidelines for anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders[13,25]. The authors (Madden S and Hay P) then conducted a new database search dated Jan 2014 to July 21 2014 using (1) PubMed and (2) the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCRCT) Issue 6 of 12, June 2014 using search terms “anorexia nervosa” and “treatment”.

Trials were included if they were completed, published in English, reported a randomized comparison of different treatment settings or different lengths of inpatient treatment, were of participants meeting diagnostic criteria for AN and where the primary outcomes were an increase in weight and reduction in eating disorder psychopathology.

Trials were assessed for risk of bias and quality according to the Cochrane handbook[26] by two authors (Madden S and Hay P) Risk of bias was assessed on adequacy of randomization procedure and allocation concealment (i.e., masking of group assignment), use of blinding in outcome assessments and data analysis applying an intention to treat analysis. Data were extracted on trial quality, participant features and setting, main outcomes and attrition.

The article is not a basic research or clinical research article and did not use biostatistics.

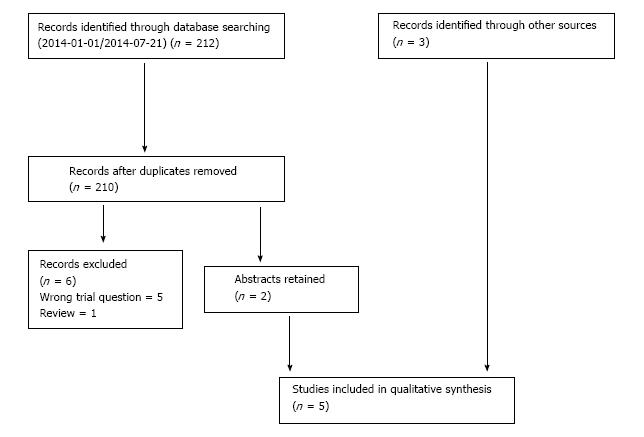

Three trials[20,21,27] were sourced from the previous reviews[13,25]. The Pubmed search resulted in 192 titles for inspection and 7 abstracts for inspection of which 5 were not trials of treatment setting[28-32] and one was a review[33] and one new trial[34] was identified. The CCRCT Issue 6 of 12, June 2014 (n = 797723) search resulted in 20 titles for inspection of which two were duplicates and one new trial[29] was identified (Figure 1).

Of the five included studies, two compared inpatient treatment to outpatient treatment[20,21], one compared different lengths of inpatient treatment[29], one compared inpatient treatment to partial hospitalization[22] and one compared partial hospitalization with outpatient treatment[27]. These trials are presented in detail in Table 1.

| Ref. | Quality | Participants | Intervention | Outcome at end of treatment | Outcome at End of follow-up |

| Crisp et al[20], | Intention to treatment analysis, clear description of treatment and clear description of methodological problems High attrition rate, randomisation not described, lack of blinding, no power analysis and small numbers per group | 90 adult female patients with DSM-IIIR AN with an illness duration of less than 10 yr. Specialist eating disorder service United Kingdom | Specialist, intensive inpatient treatment followed by 12 outpatient sessions 12 Outpatient individual and family psychotherapy including 4 sessions of dietary counselling 10 monthly outpatient group psychotherapy sessions (patient and parents) 4 sessions of dietary counselling Single assessment | Outcome took place 12 mo after the initial assessment regardless of when treatment finished All four groups increased weight significantly with weight gain in option 1 (9.6 kg), option 2 (9.0 kg), option 3 (10.1 kg) all being significantly higher than in option 4 (3.2 kg). All groups showed significant improvement in the Morgan-Russell scale. Groups 1 and 2 to P < 0.01 and groups 3 and 4 to P < 0.05 2 All groups showed significant improvement in the Morgan-Russell scale. Groups 1 and 2 to P < 0.01 and groups 3 and 4 to P < 0.05 | 2 yr follow up Only available for Individual outpatient and single assessment groups. Participants who received individual outpatient treatment had significantly higher weight, BMI, and mean matched population weight changes than the assessment only group. The treatment group experienced significantly greater improvement in the socioeconomic adjustment subscale or the Morgan Russell scale but there was not significant difference in other subscales or the global score of the Morgan-Russell scale |

| Kong[27] | Apriori power analysis and low attrition rate. Unclear blinding and concealment of randomisation. Small numbers per group and no intention to treat analysis | 50 adult female participants with DSM-IV eating disorder. AN (32%), BN (42%) and EDNOS (19%). Specialist eating disorder service South Korea | Day treatment program. Multidisciplinary 4 d a week program for 8 to 14 wk Outpatient treatment (IPT, CBT) for 4 to 24 mo | Eating behaviours (binging and purging) EDI-2; weight and BMI; psychological symptoms EDI-2: depression (BDI) and self esteem (RSES). DTP patients compared to controls showed significantly less psychological symptoms of eating disorders (EDI-2), significantly less binge eating and purging, significantly higher mood and self esteem and significantly greater weight gain in AN patients | No follow up reported |

| Gowers et al[21] | Adequate allocation concealment with blinded assessors, apriori power analysis and adequately powered as a superiority trial with intention to treat analysis. High attrition rate | 167 male and female adolescents (12 to 18 yr) with DSM-IV AN. England | Multi-disciplinary inpatient care in child and adolescent psychiatric units. ED pecialized outpatient care including motivational interviewing, CBT and family counselling Generic outpatient psychiatry treatment | Morgan Russell average outcome scale, HONOSCA (health of the nation outcome scale for Children and Adolescents)- clinician reported, EDI-2, HONOSCA self report, Family assessment device (FAD), Mood and Feeling questionnaire, BMI and Weigh for height | 1 and 2 yr follow-up No significant differences in outcomes between the three interventions. Outpatient treatment more cost effective with higher treatment adherence. Increased parental satisfaction with specialist eating disorder treatment |

| Herpertz-Dahlmann et al[22] | Adequate allocation concealment with blinded assessors, apriori power analysis and adequately powered as a non-inferiority trial with intention to treat analysis. Low attrition rate | 172, female patients aged 11 to 18 years with DSM-IV AN with a BMI below the 10th centile and their first admission to hospital for AN. The setting was 5 university hospitals and one general hospital for general child and adolescent psychiatry in Germany | 3 wk inpatient admission followed by day patient treatment based on weight restoration, nutritional counselling, CBT and family therapy until patients maintained their target weight for 2 wk 3 wk inpatient admission followed by inpatient treatment based on weight restoration, nutritional counselling, CBT and family therapy until patients maintained their target weight for 2 wk | Primary outcome was the difference in BMI between admission and follow-up. Secondary outcome measures included: Morgan-Russell Outcome Scores, EDI-2, Brief Symptom inventory total scores, eating disorder readmission and the difference in cost between the two programs No significant difference in primary outcome. Insurance costs 20% less in day treatment | 12 mo follow-up. No significant differences in primary and secondary outcome measures. Insurance costs 20% less in day treatment |

| Madden et al[34] | Adequate allocation concealment with blinded assessors, apriori power analysis and adequately powered as a superiority Low attrition rate | 82 participants aged 12 to 18 yr, medically unstable with DSM-IV AN of less than 3 yr duration | Brief inpatient tabilizationn for medical tabilization (MS) (av. 22 d) followed by 20 sessions of outpatient family based treatment (FBT) Inpatient hospitalisation for weight restoration (WR) to 90% expected body weight (EBW) (38 d) followed by 20 sessions of outpatient manualised FBT | Outcomes at the end of treatment included the percentage of patients at full and partial remission, the percentage EBW and EDE global scores There were no significant differences between groups | 12 mo follow up. Primary outcome was the number of days of hospitalisation following the initial admission Secondary outcome was the total hospital days used to and the percentage of patients at full and partial remission. Other outcomes included the percentage change in EDE global scores from baseline, readmission rates and the percentage of patients requiring treatment post protocol The only significant difference between groups was the total number of hospital days used which was significantly higher in the WR group |

Of the two trials to compare inpatient treatment to outpatient treatment one included adult females[20] and one included male and female adolescents[21]. In both of these trials, participants in all of the active treatment arms showed significant improvements in weight and significant reductions in eating disorder psychopathology with the Crisp et al[20] trial demonstrating significantly better outcomes in both weight and eating disorder pathology, as measured by the Morgan-Russell scale, in the active treatment arms when compared with a single assessment. Additionally Gowers et al[35] reported improved treatment adherence and cost effectiveness with outpatient treatment, when compared to inpatient treatment, and higher parent satisfaction with specialist outpatient treatment. Patient satisfaction was reported to be highest with specialist treatment either in the inpatient or outpatient setting.

One trial compared different lengths of inpatient treatment, comparing brief hospitalization for medical stabilization with prolonged hospitalization for weight normalization[34]. In this trial there was no significant differences in outcome as measured by changes in weight and eating disorder pathology measured by Eating Disorder Examination[36]. Trial participants in the medical stabilization arm used significantly fewer total hospital days to 12 mo follow up than participants in the weight restoration arm resulting in significant costs savings.

Partial hospitalization was compared to both inpatient treatment[22] and outpatient treatment[27]. When partial hospitalization was compared to inpatient treatment there was no difference in patient outcomes at either the end of treatment or at 12 mo follow up though treatment costs were reported to be 20% less in the partial hospitalization arm[22]. Partial hospitalization was, however reported to lead to significantly better outcomes compared to outpatient treatment with significantly less psychological symptoms, significantly less binge eating and purging, significantly higher weight gain and significantly higher mood and self-esteem[27].

Of the five trials only one demonstrated differences in treatment outcomes for AN in different treatment settings, notably better weight and psychological outcomes for those treated with partial hospitalization compared to outpatient treatment[27]. This trial, however, had a moderate risk of bias. While the trial had a low attrition rate, subject numbers were low (n = 50) and less than one third of the patients had AN (n = 14) with the remainder meeting diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified. There was no intention to treat analysis and it was unclear if the outcome assessor carrying out the statistical analysis was blind to patient allocation.

None of the other four trials showed differences in treatment outcomes for AN in adults or adolescents based on treatment settings. The treatment studies did demonstrate reduced costs for shorter inpatient hospital admissions compared with longer inpatient hospitalization[34] and reduced costs for partial hospitalization[22] and outpatient treatment[35] compared to inpatient care. On the basis of treatment outcome it is not possible to recommend one treatment setting over another, however, based on the consistent finding of increased costs it is difficult to support the use of inpatient treatment in AN in the absence of medical instability or other risk issues and even in these circumstances difficult to support inpatient treatment beyond medical stabilization[15,17,34].

These four trials were of moderate to high quality with the risk of bias minimized through the use of intention to treat analysis in all of these trials and in the three most recent trials, adequate allocation concealment, blinded assessors and apriori power analysis[21,22,34]. The number of trials is, however, small and compares different aged populations including adults[20] and adolescents[21,22,34], different treatment setting comparisons with only the one trial comparing partial hospitalization with inpatient treatment being adequately powered as a non-inferiority trial[22].

Strengths of this present review included the use of two authors in the literature search and evaluation of articles and data extraction. The main limitations were the inclusion of English language and use of published papers only.

It is clear is that whilst all of these trials are supportive of treatment in less intensive and restrictive settings more research is needed comparing both different treatment settings and different lengths of inpatient stays before conclusive recommendations can be made regarding the optimum treatment setting in AN. This is particularly the case in adults with AN where studies have been of lower quality. It is also important that when new studies are planned that they are adequately powered as non-inferiority trials.

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious disorder incurring high treatment costs, particularly due to hospitalization. While the complications of AN have been well documented, there is limited evidence to guide as to what is the most appropriate treatment setting. Current expert consensus and guidelines support outpatient care as the first line treatment in AN.

Treatment settings for AN include inpatient, partial hospitalization and outpatient. Inpatient treatment programs are usually multidisciplinary and treatment focuses on weight restoration, normalizing eating behavior and facilitating psychological change. Partial hospitalization or day programs are similar to inpatient treatment but are potentially more flexible and thus amenable to matching the individual level of motivation for change. Outpatient treatments provide care in the least restrictive setting and thus are favored by current psychiatric practice. Current evidence including a recent meta-analysis of 57 clinical trials in AN that found no difference in treatment effects based on the style of therapy or treatment setting.

The present article aims to assess the effects of different treatment settings including inpatient, partial hospitalization and outpatient on treatment outcomes in AN and to assess the effects of continuing hospitalization for weight normalization compared with brief hospitalization for medical stabilization in AN using a systematic review. Five studies were identified, two comparing inpatient treatment to outpatient treatment, one study comparing different lengths of inpatient treatment, one comparing inpatient treatment to day patient treatment and one comparing day patient treatment with outpatient treatment.

The findings of this systematic review are supportive of the treatment of AN in less intensive and restrictive settings, though more research is needed comparing both different treatment settings and different lengths of inpatient stays before conclusive recommendations can be made regarding the optimum treatment setting in AN.

Anorexia nervosa is characterized by the restriction of energy intake relative to requirements leading to a significantly low weight for gender, age, developmental trajectory and height. Individuals with AN maintain an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming overweight even though they are underweight. They have a disturbance in the way in which they perceive their body weight and shape, there is undue influence of weight and shape on self evaluation and/or they deny the seriousness of their illness.

This study compared the outcomes in anorexia nervosa in different treatment settings, and found a preliminary support for the treatment in less restrictive settings.

P- Reviewer: Akgül S, Wang WH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing 2013; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW, Susser ES, Linna MS, Sihvola E, Raevuori A, Bulik CM, Kaprio J, Rissanen A. Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1259-1265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 284] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR. Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1284-1292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 276] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Preti A, Girolamo Gd, Vilagut G, Alonso J, Graaf Rd, Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Pinto-Meza A, Haro JM, Morosini P. The epidemiology of eating disorders in six European countries: results of the ESEMeD-WMH project. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:1125-1132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 319] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wade TD, Bergin JL, Tiggemann M, Bulik CM, Fairburn CG. Prevalence and long-term course of lifetime eating disorders in an adult Australian twin cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:121-128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 180] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Steinhausen HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1284-1293. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 947] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10-15 years in a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:339-360. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Katzman DK. Medical complications in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37 Suppl:S52-S59; discussion S87-S89. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Hatch A, Madden S, Kohn M, Clarke S, Touyz S, Williams LM. Anorexia nervosa: towards an integrative neuroscience model. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18:165-179. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Swinbourne J, Hunt C, Abbott M, Russell J, St Clare T, Touyz S. The comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: prevalence in an eating disorder sample and anxiety disorder sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46:118-131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Talbot A, Hay P, Buckett G, Touyz S. Cognitive deficits as an endophenotype for anorexia nervosa: An accepted fact or a need for re-examination? Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:15-25. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Talbot A; NICE. Eating Disorders: Core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. USA: National Clinical Practice Guideline CG9 2004; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, Madden S, Newton R, Sugenor L, Touyz S, Ward W. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:977-1008. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 316] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lock J. Evaluation of family treatment models for eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:274-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Golden NH, Katzman DK, Kreipe RE, Stevens SL, Sawyer SM, Rees J, Nicholls D, Rome ES. Eating disorders in adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:496-503. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | La Puma M, Touyz S. Dean H, Williams H, Thornton C. Day hospital treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa: evidence and practice. Interventions for body image and eating disorders: evidence and practice. Melbourne: IP Communications 2009; 95-118. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Hartmann A, Weber S, Herpertz S, Zeeck A. Psychological treatment for anorexia nervosa: a meta-analysis of standardized mean change. Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80:216-226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Willinge AC, Touyz SW, Thornton C. An evaluation of the effectiveness and short-term stability of an innovative Australian day patient programme for eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18:220-233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Thornton C, Touyz S, Willinge AC, La Puma M. Day hospital treatment of paitents with Anorexia Nervosa. Interventions for body image and eating disorders: evidence and practice. Melbourne: IP Communications 2009; 140-156. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Crisp AH, Norton K, Gowers S, Halek C, Bowyer C, Yeldham D, Levett G, Bhat A. A controlled study of the effect of therapies aimed at adolescent and family psychopathology in anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:325-333. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 196] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Köppel C, Wagemann A. Plasma level monitoring of D,L-verapamil and three of its metabolites by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1991;570:229-234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 181] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Schwarte R, Krei M, Egberts K, Warnke A, Wewetzer C, Pfeiffer E, Fleischhaker C, Scherag A, Holtkamp K. Day-patient treatment after short inpatient care versus continued inpatient treatment in adolescents with anorexia nervosa (ANDI): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1222-1229. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 154] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Thornton C, Beumont P, Touyz S. The Australian experience of day programs for patients with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:1-10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Touyz S, Thornton C, Rieger E, George L, Beumont P. The incorporation of the stage of change model in the day hospital treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;12 Suppl 1:I65-I71. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hay P. A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005-2012. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:462-469. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 196] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Higgins JPT, Green S, editors . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Kong S. Day treatment programme for patients with eating disorders: randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51:5-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | White HJ, Haycraft E, Madden S, Rhodes P, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Wallis A, Kohn M, Meyer C. How do parents of adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa interact with their child at mealtimes? A study of parental strategies used in the family meal session of family-based treatment. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:72-80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Le Grange D, Accurso EC, Lock J, Agras S, Bryson SW. Early weight gain predicts outcome in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:124-129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hergenroeder AC, Wiemann CM, Henges C, Dave A. Outcome of adolescents with eating disorders from an adolescent medicine service at a large children‘s hospital. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2014;27:49-56. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ngo M, Isserlin L. Body weight as a prognostic factor for day hospital success in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Eat Disord. 2014;22:62-71. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sly R, Mountford VA, Morgan JF, Lacey JH. Premature termination of treatment for anorexia nervosa: differences between patient-initiated and staff-initiated discharge. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:40-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, Schmidt U, van Elburg AA. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:845-852. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Madden S, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Wallis A, Kohn M, Lock J, Le Grange D, Jo B, Clarke S, Rhodes P, Hay P. A randomized controlled trial of in-patient treatment for anorexia nervosa in medically unstable adolescents. Psychol Med. 2014;Jul 14; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 427] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Gowers SG, Clark AF, Roberts C, Byford S, Barrett B, Griffiths A, Edwards V, Bryan C, Smethurst N, Rowlands L. A randomised controlled multicentre trial of treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa including assessment of cost-effectiveness and patient acceptability - the TOuCAN trial. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1-98. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cooper Z, Cooper PJ, Fairburn CG. The validity of the eating disorder examination and its subscales. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:807-812. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |