Abstract

Perceptions of HIV acquisition risk and prevalence shape sexual behavior in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). We used data from the Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa baseline survey. Data were collected through home-based interviews of 5059 people ≥ 40 years old. We elicited information on perceived risk of HIV acquisition and HIV prevalence among adults ≥ 15 and ≥ 50 years old. We first describe these perceptions in key subgroups and then compared them to actual estimates for this cohort. We then evaluated the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and accurate perceptions of prevalence in regression models. Finally, we explored differences in behavioral characteristics among those who overestimated risk compared to those who underestimated or accurately estimated risk. Compared to the actual HIV acquisition risk of < 1%, respondents vastly overestimated this risk: 35% (95% CI: 32–37) and 34% (95% CI: 32–36) for men and women, respectively. Respondents overestimated HIV prevalence at 53% (95% CI: 52–53) for those ≥ 15 years old and 48% (95% CI: 48–49) for those ≥ 50 years old. True values were less than half of these estimates. There were few significant associations between demographic characteristics and accuracy. Finally, high overestimators of HIV prevalence tested themselves less for HIV compared to mild overestimators and accurate reporters. More than 30 years into the HIV epidemic, older people in a community with hyperendemic HIV in SSA vastly overestimate both HIV acquisition risk and prevalence. These misperceptions may lead to fatalism and reduced motivation for prevention efforts, possibly explaining the continued high HIV incidence in this community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tremendous resources have been invested to educate populations in regions of high HIV prevalence, such as South Africa, about HIV risk and prevention. However, little data exist to assess perceptions of HIV acquisition risk and prevalence at the population level, especially among older adults. In order to prevent HIV in high-risk populations, it is critically important to understand current perceptions of HIV and potential knowledge deficits among people living in areas of high prevalence and design interventions to fill these gaps (Rosenberg et al., 2017; van Heerden et al., 2017; GHO, 2018).

Risk perception plays a crucial role in risk behavior (Brewer et al., 2004; Gerrard et al., 1993, 1996; Kalichman & Cain, 2005). Accurate risk perception may promote protective behavior, and underestimation of risk may lead to more risky behavior (Brewer et al., 2004; Kalichman & Cain, 2005). Moreover, accurate perceptions of HIV risk are necessary in shaping rational action, whereas inaccurate perceptions deprive individuals of agency (Akwara et al., 2003; Noroozinejad et al., 2013). Overestimation of HIV acquisition risk and HIV prevalence may engender fatalism, leading to greater risk-taking and less care-seeking (Hess & Mbavu, 2010; Sileo et al., 2019). In contrast, if HIV acquisition risk and HIV prevalence are underestimated, people may not sufficiently protect themselves against potential infection with HIV. Therefore, it is important that individuals have accurate perceptions about HIV acquisition risk and prevalence. However, perceptions of risk of acquisition and prevalence of HIV among heterosexual partners are unknown in many regions of high HIV prevalence, including South Africa.

Several studies in the U.S. have shown a wide variation in the understanding of HIV prevalence by the general population (Kalichman & Cain, 2005; Rosenberg et al., 2016; White & Stephenson, 2016). For instance, one study showed that people were able to estimate their local HIV prevalence and that perceptions of HIV prevalence can impact sexual risk behavior. In prior studies, underestimation of HIV prevalence has been associated with having multiple sexual partners, less HIV testing, more high-risk sexual behavior and higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases (Kalichman & Cain, 2005). Recent findings from the Health and Aging in Africa: Longitudinal Studies of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa (HAALSI) study report HIV prevalence of 23% among adults aged 40 years and above in 2014–2015 in Agincourt, South Africa, and a prevalence of 20% in adults aged 50 years and older (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2013; M. S. Rosenberg et al., 2017). As such, it is important to understand perceptions of prevalence among adults in South Africa in a setting where the burden of HIV is especially high, as they may be a potential area for programmatic intervention to reduce future transmission incidence (Rosenberg et al., 2017; van Heerden et al., 2017). Using data from the HAALSI baseline survey, we measured HIV acquisition risk and HIV prevalence perceptions among older adults living in a rural South African community with a very high prevalence of HIV. We compared these perceptions to the estimates of their true value and establish the extent to which the accuracy of these perceptions was a function of sociodemographic factors.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study used data from the HAALSI baseline survey. HAALSI is a study of older adults that seeks to characterize cardiovascular disease, cognitive health, dementia and HIV (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2018). The study included men and women in rural South Africa that are 40 years and older. A total of 5059 people participated (2345 men (46.4%) and 2714 women (53.6%)) with an overall response rate of 85.9% (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2018). The HAALSI cohort is situated in the Agincourt health and socio-demographic surveillance system (HDSS), which annually updates social, demographic and health changes of 116,000 participants (Kahn et al., 2012). Data collection took place from November 2014 until November 2015. Inclusion criteria were being 40 years of age or older on July 1, 2014, and a resident in the Agincourt study area for at least one year before the HDSS update round in 2013 (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2018). Fieldworkers were residents in the study area who were locally trained to collect data at the household level. Responses were recorded via an individual computer-assisted personal interviews system and were checked internally to ensure data quality and completeness (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2018).

Measures

Four questions about perceptions of HIV risk and prevalence were extracted from the survey. Questions regarding HIV risk perception included:

What do you think the probability is that a man would become infected with HIV from only one act of unprotected vaginal intercourse with an already infected woman? Probability a man would become infected = 1 in ...

What do you think the probability is that a woman would become infected with HIV from only one act of unprotected vaginal intercourse with an already infected man? Probability a woman would become infected = 1 in ...

In addition, there were two distinct questions asked about the perception of HIV prevalence, as follows:

Out of every 100 adults 15 years or older, how many do you think have been infected with HIV? Range 0–100.

Out of every 100 adults 50 years or older, how many do you think have been infected with HIV? Range 0–100.

We abbreviate these questions as follows: (1) perceived acquisition risk for a man, (2) perceived acquisition risk for a woman, (3) prevalence ≥ 15 years, and (4) prevalence ≥ 50 years.

To determine accuracy of the perceptions, we defined a range of responses that may be considered plausible based on the current literature. Perceived prevalence was defined as accurate when reported in the range of 9.9–29.9% for the question “prevalence ≥ 15 years” (the actual percentage is 19.9) and 10–30% for “prevalence ≥ 50 years” (the actual percentage is 20.0) (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2013; Rosenberg et al., 2017; World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). The chosen range of accuracy for HIV acquisition risk perception was equal to the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) presented in a study by Boily et al. (2009), ranging from 0.09% to 2.70% (Patel et al., 2014), which corresponds to a participant response between 1 in 1111 and 1 in 37 for the questions acquisition risk for men and for women. The correlates of “accurate” perceptions were also explored in logistic regression analyses. This analysis had as an outcome a range of plausible or “accurate” answers as defined above.

Statistical Analysis

We performed three analytical steps for each of the four questions of interest. First, we describe the sociodemographic and health characteristics of the overall cohort. We then display the distribution of estimates provided for all four metrics of interest and the percentage of people who reported “accurate” perceptions of acquisition risk and prevalence in the cohort overall, based on our given definitions. Next, we used multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess the relationship between accurate reporting of HIV prevalence and several key sociodemographic characteristics including age, sex, educational attainment, HIV status, household wealth and marital status. In a supplementary regression analysis, we assessed whether these same key sociodemographic factors were associated with accurate estimates of HIV acquisition risk. Finally, we explored the fatalism hypothesis by describing differences in the core demographic variables and health behaviors across groups defined by the participants’ accuracy in assessing HIV acquisition risk and prevalence. This analysis was performed in two ways. First, we compared these characteristics in those who underestimate HIV prevalence or HIV acquisition risk as compared to those who overestimate this risk. Second, we compared these characteristics across groups defined by the severity of overestimation (high overestimators, mild overestimators, accurate reporters). The health behaviors of interest for this analysis were two measures of self-reported sexual risk behavior, namely having sex without a condom with someone you know is HIV positive and having sex in exchange for money, goods or services, and one question about whether the participant had ever been tested for HIV.

Age was categorized into the following groups: “40–49 years,” “50–59 years,” “60–69 years,” “70–79 years” and “ ≥ 80 years.” Education categories were defined as follows: “no formal education,” “some primary (1–7 years),” “some secondary (8–11 years),” and “secondary or more (12 + years).” Household wealth was quantified according to quintiles of a household asset index, based on the methodology of Filmer and Pritchett (2001), with one representing the poorest and five the richest households. Household wealth was measured by questioning about residence and ownership of certain indicators, such as car or television (Geldsetzer et al., 2018). Dried bloodspots (DBS) were obtained through finger pricks of consenting participants. DBS were tested for HIV antibodies and viral load as explained in a prior study by Gómez-Olivé et al. (2018). In these analyses, HIV status was divided into two categories: “HIV negative” and “HIV positive.” Marital status was categorized as “never married,” “currently married or living with partner,” “separated,” “divorced,” and “widowed.” Finally, we also explored three self-reported behavioral variables: (1) ever being tested for HIV, (2) condom use with someone you know is HIV positive, and (3) having had sex in exchange for money, drugs, goods or services. Each of these questions was answered with a binary “yes” or “no.” Analyses were performed using the statistical program SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 25).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The population of interest in this study was the subset of HAALSI participants who had responded to at least one of the four questions of interest. Of the 5059 HAALSI participants, 4276 (84.5%) responded to at least one of these four questions. Response rates for the four questions were 80.2% for the questions about acquisition risk for a man, acquisition risk for a woman and prevalence ≥ 15 years and 80.1% for prevalence ≥ 50 years (Table 1). We provide a summary of differences in demographic characteristics between responders and non-responders to each of these questions (Appendix Tables 6 and 7). Among all respondents, 45.7% were men, the mean age was 60.8 (± 12.6) years, and nearly half (42.7%) of the respondents had no formal education (Table 1). Of the 3836 (89.7%) participants who consented to DBS HIV testing, 2948 (76.9%) tested negative, while 888 (23.1%) tested positive for HIV (Table 1).

Perceptions of HIV Acquisition Risk

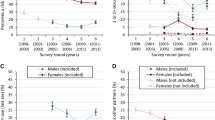

The mean perceived risk for a man becoming infected after one sex act with a woman living with HIV was 1 in 2.8 (± 5.6), which corresponds to 35.2%. For a woman, this number was slightly lower, with a mean perceived risk of 1 in 2.9 (± 5.0), corresponding to 34.2% (Table 2). Histograms (Fig. 1a, b) display distributions of these values and demonstrate that people from this South African cohort most frequently estimate the risk of acquiring HIV from one sex act to be between 1 in 1 and 1 in 10, for both a man (99.3%) and a woman (98.8%), with the most frequently stated risk being 1 in 1 (57.7% for a man, 56.6% for a woman). Those who did not accurately estimate HIV acquisition risk all overestimated the risk of acquiring HIV.

Histograms depicting the variation in perceptions of a per sex act acquisition risk for a man having vaginal intercourse with a woman living with HIV, b per sex act acquisition risk for a woman having vaginal intercourse with a man living with HIV, c prevalence of HIV in a population of 15 years or older and d prevalence of HIV in a population of 50 years or older

Perceptions of HIV Prevalence

HAALSI participants reported that they perceived HIV prevalence among people aged 15 or older to be 52.7 in 100 (± 26.7). Among people aged 50 or older, the perceived prevalence reported by HAALSI participants was 48.1 in 100 (± 27.4) (Table 2). Histograms (Fig. 1c, d) of the responses for both ≥ 15 and ≥ 50 years old show high variability, clearly demonstrating this population’s limited understanding of the true HIV prevalence.

Evaluating the Association Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Perceptional Accuracy

No significant differences were found in perceptions of HIV acquisition risk and prevalence by sex, age, education and HIV status. Moreover, univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses likewise uncovered no significant differences in the unadjusted or adjusted association between perceptional accuracy and sex, education, HIV status and household wealth (Table 3, Appendix Table 8). However, older people appeared to be significantly better at accurately estimating the HIV prevalence among people aged 50 or older (p = 0.04). The odds ratios (ORs) that described accurate reporting of HIV prevalence in this group were 1.26 (p = 0.05) for “50–59 years,” 1.41 (p < 0.01) for “60–69 years,” and 1.33 (p = 0.05) for “70–79 years,” compared to people aged 40–49 years (Table 3). This indicates that the HAALSI cohort members have a slightly more accurate perception of HIV prevalence in their own demographic group than for the population overall. Moreover, the regression analysis showed that divorced people were less likely to accurately estimate the HIV prevalence among people over 15 years (OR 0.36, p = 0.01) and 50 (OR 0.56, p = 0.03) years old, with the reference group being people who were never married. People who had never been tested for HIV were less likely to accurately estimate the HIV prevalence both among those 15 years or older (OR 0.48, p < 0.01) and among those 50 years or older (OR 0.75, p < 0.01), compared to those who had ever been tested for HIV. Finally, we found no relationship between our self-reported measures of sexual risk behavior and the outcomes of interest (Table 3, Appendix Table 8).

Exploring the Fatalism Hypothesis

There were few people who underestimated HIV prevalence over 15 years (n = 126) and 50 years (n = 183) old. Therefore, the vast majority of inaccurate reports were overestimates. We performed a subanalysis to examine differences in sociodemographic and health behavior characteristics among people who overestimated HIV prevalence compared to those who estimated accurately (Table 4). We found accurate reporters were slightly wealthier compared to those who overestimated HIV prevalence in both age groups (Table 4). Furthermore, we found more women who overestimated HIV prevalence than accurately estimated (54.6% versus 50.1%, p = 0.03) (Table 4). Though very few people underestimated HIV prevalence, we performed a second subanalysis to compare characteristics of those who under- and overestimate risk and prevalence (Appendix Table 9). In this supplemental analysis, we found that overestimators had greater educational attainment and were wealthier than people who underestimated HIV prevalence over 15 years old (Appendix Table 9).

In exploring the fatalism theory, we found no significant differences in sexual risk behavior for those who overestimate HIV acquisition risk compared to those who accurately do so. However, we found a significant difference in HIV testing behavior between those who overestimate HIV prevalence in people over 15 and 50 years old and those who accurately do so (Table 5). These results show that a lower proportion of people who provide high overestimates of HIV prevalence have ever been tested for HIV. However, we found no significant differences in responses to the sexual behavior questions between these two groups.

We also evaluated the relationship between overestimation of both HIV prevalence and acquisition risk and participant characteristics (Appendix Tables 10 and 11). In this analysis, we found that high overestimators of HIV prevalence in adults over 50 years of age were less wealthy than mild overestimators and accurate reporters (Appendix Table 10). Finally, we found no meaningful differences in participant characteristics and the degree of overestimating HIV acquisition risk (Appendix Table 11).

Discussion

This study explored perceptions of HIV acquisition risk and prevalence among older adults in rural South Africa. Participants provided a very wide range of estimates for both risk and prevalence, and overall low rates of accuracy about these core principles related to the HIV epidemic. When considering an “actual” risk of acquiring HIV from one heterosexual sex act with a man or woman living with HIV being 1 in 1111 to 1 in 37, we found that most older adults overestimated this risk, providing frequencies from 1 in 1 to 1 in 10. In contrast, there was no obvious pattern in the perceived prevalence and few participants gave accurate estimates of this key parameter.

Accurately estimating HIV acquisition risk and prevalence was not associated with sex, education level, HIV status, household wealth or two measures of sexual risk behavior—condom use and sex in exchange for money, drugs, foods or services. However, older adults were more likely to estimate the prevalence in their own age group with greater accuracy. There were very few people who estimated HIV acquisition risk accurately, limiting our ability to draw definitive conclusions from these questions. The implications of these findings suggest that there are few sociodemographic factors that predict whether a person can accurately estimate HIV prevalence. In particular, it appears that many people believe the risk and prevalence are extremely high. We found that high overestimators of HIV prevalence were also less likely to have ever been tested for HIV, suggesting that fatalism might be present in this population.

Explanations for this wide distribution in the perception of HIV risk and prevalence might be that, despite awareness and educational efforts that have been part of prevention strategies, a knowledge gap still exists about HIV in this high-prevalence community. This could be due to a relatively minimal emphasis on older adults in preventive educational interventions, as these programs tend to focus more on younger people (Mills et al., 2011, 2012; Negin et al., 2012; Rammohan & Awofeso, 2010). The older population seems to be a neglected group in terms of education and awareness, which is supported by the finding that they know little about HIV acquisition risk and prevalence. However, previous research has also shown that only 34% of younger adults (under the age of 25 years) have an accurate understanding of HIV acquisition and prevention despite educational efforts (UNFPA, 2015), though in our older cohort the overall accuracy was even lower at only 11.6%. It is likely that our aging cohort received much less education about HIV and thus has a more limited understanding of the disease. Another possible explanation is that, given the stigma associated with HIV infection, people do not share their HIV status in social circles, leading to further misconceptions about the prevalence and risk of acquiring HIV in this context (Parker & Aggleton, 2003; Sandelowski et al., 2004; Treves-Kagan et al., 2017). An interesting finding is that accurately estimating acquisition risk and prevalence seem to have no significant sociodemographic predictors, except for the relationship between older age and the increased accuracy of prevalence estimation in older adults, as mentioned earlier. In particular, we hypothesized that education might be of importance in estimating risk and prevalence correctly. However, the “accurate” group had a small sample size and little variability in educational attainment generally, with 78.3% of participants having an education level below secondary school.

Several prior studies have investigated perceptions of HIV risk. However, many of these studies have focused on perceptions of lifetime risk of acquiring HIV instead of the risk of contracting HIV from one sex act (Chard et al., 2017; Clifton et al., 2016; Price et al., 2018). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the understanding of acquisition risk in an older, rural South African population. One study that did investigate the perception of per sex act HIV acquisition risk was undertaken in the U.S. among men who have sex with men (MSM). This study demonstrated substantial misperceptions of risk, with most participants overestimating the risk of acquiring HIV in a single sex act with an infected partner (Belcher et al., 2005). Our study substantiates this existing misperception of HIV risk, now confirmed in an older population in South Africa.

A study in the U.S. investigated perceptions of prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), with the main focus being HIV, in men and women (Kalichman & Cain, 2005). Results showed that people were capable of accurately estimating the HIV prevalence in their hometown. However, people who did not estimate prevalence correctly were likely to overestimate the number of people living with HIV (Kalichman & Cain, 2005). This overestimation of prevalence is similar to our findings. However, the finding that people were able to accurately estimate the HIV prevalence differs from the findings in this study. A possible reason for this discrepancy is the context and specifically the greater availability of health education in the U.S. Moreover, the participants in this study were older South Africans, who grew up under the apartheid system where the educational quality in schools was lower for the black South African population (McKeever, 2017).

This study has important implications for understanding and potentially intervening to alter sexual risk behavior at the population level. Specifically, without accurate perceptions of risk, individuals lack agency to make the best choices regarding sexual risk-taking and HIV care-seeking (Akwara et al., 2003; Noroozinejad et al., 2013). Given the dramatic overestimations of both HIV acquisition risk and prevalence in this population, there is a reason to be concerned that fatalism may be deeply rooted among many in this community (Hess & Mbavu, 2010; Sileo et al., 2019). We find preliminary evidence this may be the case in our context because our results show people who were high overestimators of the HIV prevalence were less likely to test themselves for HIV. Individuals may not feel the need to protect themselves, because they perceive that they will acquire HIV regardless (Hess & Mbavu, 2010; Sileo et al., 2019; Sterck, 2013). Prior research has shown that awareness of high HIV prevalence and difficulties in consistent condom use might contribute to a sense of fatalism regarding HIV protection (Meyer-Weitz, 2005). Some might think that overestimation of HIV risk at the population is good because people will then take less risk. However, individuals may lack information about preventing HIV transmission and thus their fatalism is more plausible (Hess & Mbavu, 2010; Sileo et al., 2019; Sterck, 2013). Moreover, if there were strongly deterrent effects of these misperceptions, one would not expect such an extremely high HIV prevalence in this community. However, more research is needed to understand how perceptions of risk shape individual behavior. Regardless of the impact of these beliefs on behavior, it would be perverse to allow individuals to remain misinformed in order to manipulate their health behaviors.

In addition to overestimation of acquisition risk, we also find a high degree of uncertainty about prevalence at the community level. This is an important, distinct concern. This community-level uncertainty could be psychologically distressing, and it could also have a range of complex behavioral effects when people meet (e.g., in sexual encounters) who hold very different beliefs about transmission risk and the probability that a community member from the opposite sex is HIV positive (Halkitis et al., 2004; Kalichman et al., 2006). In order to equalize these perceptions about HIV acquisition risk and prevalence among this population, changes are needed to existing HIV prevention strategies. Potential ideas to improve education and intervention campaigns in the future include (1) more direct engagement with the aging community, (2) stronger social marketing campaigns with targeted, accurate messages, and (3) ensuring that health workers and traditional leaders are informed about these realities. As such, it is important to increase hope that the HIV epidemic can be controlled in this population. This can be achieved by informing this population of an 80% chance of testing negative for HIV and educating them about the transmission rate, which in the age of “undetectable equals untransmittable” is considered to be zero when a person is virally suppressed on ART (Barroso et al., 2000; Cohen et al., 2016; Rodger et al., 2016).

This study had several limitations. First, the perceptions of risk and prevalence were coded into binary outcomes (accurate and not accurate) and a range was chosen to determine accuracy. This range was chosen based on the actual biological risk and estimated prevalence and what seemed to be a plausible range around the known estimate. Hence, these ranges were partially subjective. Furthermore, the state of infection can influence acquisition risk, as is known that acquisition risk during acute infection increases infectious potential by 26-fold (Hollingsworth et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2010), whereas acquisition risk when having sex with a virally suppressed person living with HIV is close to zero (Barroso et al., 2000; Cohen et al., 2016; Rodger et al., 2016). The survey did not specifically discuss acquisition risk in specific stages of disease, and thus, there may have been ambiguity on the part of the respondents. Another limitation of this study is that the estimates of HIV acquisition risk were framed only in terms of unprotected sex. This overestimation of the risk of unprotected sex may or may not be extrapolated to people’s perceptions of the risk of HIV acquisition during sex with a condom. Moreover, the questions about acquisition risk were asked in the form of a probability; although introductory textFootnote 1 was provided, this still had the potential to confuse respondents, especially those with low levels of education. Finally, we were not able to measure all potentially relevant factors, such as loss of a spouse to HIV or the influence of younger adults in the household on risk perceptions. As such, this study may be subject to residual confounding due to unobserved factors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, 30 years into the HIV epidemic there still are substantial misperceptions and uncertainty about HIV acquisition risk and prevalence among this older South African cohort. This might in fact be one of the deeper, underlying drivers of the continued spread of this disease in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in this age group. HIV education and information in this population remain insufficient. Without better understanding, individuals may be deprived of agency in making decisions about sexual risk-taking and HIV care-seeking and, if overestimating risk, may also espouse a fatalistic attitude toward prevention of this disease. Expanded and improved education and information campaigns are urgently needed to ensure that older adults have correct perceptions about key aspects of their HIV risk.

Appendix

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11.

Data Availability

Data are (partially) publicly available on the HAALSI Web site: https://haalsi.org/data. Codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Introductory text: “HIV can be transmitted when an HIV-infected person has sex with an HIV-uninfected person. However, not every sex act between an HIV-infected and an HIV-uninfected person leads to an HIV infection. In the following questions, you will be asked to estimate the probability that a sex act leads to an HIV transmission. As an example of how we will ask you to answer this question, please consider the following example: “The probability of winning the lottery is 1 in ____” (the true probability of winning the lottery is somewhere around 1 in 10 million).”

References

Akwara, P. A., Madise, N. J., & Hinde, A. (2003). Perception of risk of HIV/AIDS and sexual behaviour in Kenya. Journal of Biosocial Science, 35(3), 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932003003857.

Barroso, P. F., Schechter, M., Gupta, P., Melo, M. F., Vieira, M., Murta, F. C., Souza, Y., & Harrison, L. H. (2000). Effect of antiretroviral therapy on HIV shedding in semen. Annals of Internal Medicine, 133(4), 280–284. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-133-4-200008150-00039.

Belcher, L., Strenberg, M. R., Wolitski, R. J., Halikitis, P., & Hoff, C. (2005). Condom use and perceived risk of HIV transmission among sexually active HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.17.1.79.58690.

Boily, M., Baggaley, R. F., Wang, L., Masse, B., White, R. G., Hayes, R. J., & Alary, M. (2009). Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 9(2), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0.

Brewer, N. T., Weinstein, N. D., Cuite, C. L., & Herrington, J. E. (2004). Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 27(2), 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7.

Chard, A. N., Metheny, N., & Stephenson, R. (2017). Perceptions of HIV seriousness, risk, and threat among online samples of HIV-negative men who have sex with men in seven countries. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 3(2), e37. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.7546.

Clifton, S., Nardone, A., Field, N., Mercer, C. H., Tanton, C., Macdowall, W., Johnson, A. M., & Sonnenberg, P. (2016). HIV testing, risk perception, and behaviour in the British population. AIDS, 30(6), 943–952. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001006.

Cohen, M. S., Chen, Y. Q., McCauley, M., Gamble, T., Hosseinipour, M. C., Kumarasamy, N., Hakim, J. G., Kumwenda, J., Grinsztejn, B., Pilotto, J. H. S., Godbole, S. V., Chariyalertsak, S., Santos, B. R., Mayer, K. H., Hoffman, I. F., Eshleman, S. H., Piwowar-Manning, E., Cottle, L., Zhang, X. C., … Fleming, T. R. (2016). Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(9), 830–839. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1600693.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. H. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data–or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography, 38(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2001.0003.

Geldsetzer, P., Vaikath, M., Wagner, R., Rohr, J. K., Montana, L., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Rosenberg, M. S., Manne-Goehler, J., Mateen, F. J., Payne, C. F., Kahn, K., Tollman, S. M., Salomon, J. A., Gaziano, T. A., Bärnighausen, T., & Berkman, L. F. (2018). Depressive symptoms and their relation to age and chronic diseases among middle-aged and older adults in rural South Africa. Journals of Gerontology Series A, 74, 957–963. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly145.

Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F. X., & Bushman, B. J. (1996). Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 119(3), 390–409. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390.

Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F. X., Warner, T. D., & Smith, G. E. (1993). Perceived vulnerability to HIV infection and AIDS preventive behavior: A critical review of the evidence. In J. B. Pryor & G. D. Reeder (Eds.), The social psychology of HIV infection (pp. 59–84). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-98031-003

GHO|Number of new HIV infections - Data by WHO region. (2018). In World Health Organization (WHO). http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.HIVINCIDENCEREGIONv?lang=en

Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Angotti, N., Houle, B., Klipstein-Grobusch, K., Kabudula, C., Menken, J., Williams, J., Tollman, S., & Clark, S. J. (2013). Prevalence of HIV among those 15 and older in rural South Africa. AIDS Care, 25(9), 1122–1128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.750710.

Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Montana, L., Wagner, R. G., Kabudula, C. W., Rohr, J. K., Kahn, K., Bärnighausen, T., Collinson, M., Canning, D., Gaziano, T., Salomon, J. A., Payne, C. F., Wade, A., Tollman, S. M., & Berkman, L. (2018). Cohort profile: Health and ageing in Africa: A longitudinal study of an INDEPTH community in South Africa (HAALSI). International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(3), 689–690. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx247.

Halkitis, P. N., Zade, D. D., Shrem, M., & Marmor, M. (2004). Beliefs about HIV non-infection and risky sexual behavior among MSM. AIDS Education and Prevention, 16(5), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.16.5.448.48739.

Hess, R. F., & Mbavu, M. (2010). HIV/AIDS fatalism, beliefs and prevention indicators in Gabon: Comparisons between Gabonese and Malians. African Journal of AIDS Research, 9(2), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2010.517479.

Hollingsworth, T. D., Anderson, R. M., & Fraser, C. (2008). HIV-1 Transmission, by stage of infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 198(5), 687–693. https://doi.org/10.1086/590501.

Kahn, K., Collinson, M. A., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Mokoena, O., Twine, R., Mee, P., Afolabi, S. A., Clark, B. D., Kabudula, C. W., Khosa, A., Khoza, S., Shabangu, M. G., Silaule, B., Tibane, J. B., Wagner, R. G., Garenne, M. L., Clark, S. J., & Tollman, S. M. (2012). Profile: Agincourt health and socio-demographic surveillance system. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(4), 988–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys115.

Kalichman, S. C., & Cain, D. (2005). Perceptions of local HIV/AIDS prevalence and risks for HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections: Preliminary study of intuitive epidemiology. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 29(2), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2902_4.

Kalichman, S. C., Eaton, L., Cain, D., Cherry, C., Pope, H., & Kalichman, M. (2006). HIV treatment beliefs and sexual transmission risk behaviors among HIV positive men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(5), 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-006-9066-3.

McKeever, M. (2017). Educational inequality in apartheid South Africa. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(1), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216682988.

Meyer-Weitz, A. (2005). Understanding fatalism in HIV/AIDS protection: The individual in dialogue with contextual factors. African Journal of AIDS Research, 4(2), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085900509490345.

Miller, W. C., Rosenberg, N. E., Rutstein, S. E., & Powers, K. A. (2010). Role of acute and early HIV infection in the sexual transmission of HIV. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 5(4), 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a0d3a.

Mills, E. J., Bärnighausen, T., & Negin, J. (2012). HIV and aging—preparing for the challenges ahead. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(14), 1270–1273. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1113643.

Mills, E. J., Rammohan, A., & Awofeso, N. (2011). Ageing faster with AIDS in Africa. Lancet, 377(9772), 1131–1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62180-0.

Negin, J., Bärnighausen, T., Lundgren, J. D., & Mills, E. J. (2012). Aging with HIV in Africa: The challenges of living longer. AIDS, 26, S1–S5. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283560f54.

Noroozinejad, G., Yarmohmmadi Vasel, M., Bazrafkan, F., Sehat, M., Rezazadeh, M., & Ahmadi, K. (2013). Perceived risk modifies the effect of HIV knowledge on sexual risk behaviors. Frontiers in Public Health, 1, 33. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2013.00033.

Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine, 57(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00304-0.

Patel, P., Borkowf, C. B., Brooks, J. T., Lasry, A., Lansky, A., & Mermin, J. (2014). Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: A systematic review. AIDS, 28(10), 1509–1519. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000298.

Price, J. T., Rosenberg, N. E., Vansia, D., Phanga, T., Bhushan, N. L., Maseko, B., Brar, S. K., Hosseinipour, M. C., Tang, J. H., Bekker, L.-G., & Pettifor, A. (2018). Predictors of HIV, HIV risk perception, and HIV worry among adolescent girls and young women in Lilongwe, Malawi. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 77(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001567.

Rammohan, A., & Awofeso, N. (2010). Addressing HIV prevention and disease burden among Africans aged over 50 years. Tropical Doctor, 40(3), 171–172. https://doi.org/10.1258/td.2010.090492.

Rodger, A. J., Cambiano, V., Bruun, T., Vernazza, P., Collins, S., van Lunzen, J., Corbelli, G. M., Estrada, V., Geretti, A. M., Beloukas, A., Asboe, D., Viciana, P., Gutiérrez, F., Clotet, B., Pradier, C., Gerstoft, J., Weber, R., Westling, K., Wandeler, G., Lundgren, J. (2016). Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(2), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.5148.

Rosenberg, E. S., Grey, J. A., Sanchez, T. H., & Sullivan, P. S. (2016). Rates of prevalent HIV infection, prevalent diagnoses, and new diagnoses among men who have sex with men in US states, metropolitan statistical areas, and counties, 2012–2013. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 2(1), e22. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.5684.

Rosenberg, M. S., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., Rohr, J. K., Houle, B. C., Kabudula, C. W., Wagner, R. G., Salomon, J. A., Kahn, K., Berkman, L. F., Tollman, S. M., & Bärnighausen, T. (2017). Sexual behaviors and HIV status: A population-based study among older adults in rural South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 74(1), e9–e17. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001173.

Sandelowski, M., Lambe, C., & Barroso, J. (2004). Stigma in HIV-positive women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x.

Sileo, K. M., Bogart, L. M., Wagner, G. J., Musoke, W., Naigino, R., Mukasa, B., & Wanyenze, R. K. (2019). HIV fatalism and engagement in transactional sex among Ugandan fisherfolk living with HIV. SAHARA J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17290376.2019.1572533.

Sterck, O. (2013). HIV/AIDS and fatalism: should prevention campaigns disclose the transmission rate of HIV? Journal of African Economies, 23(1), 53–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejt018.

Treves-Kagan, S., El Ayadi, A. M., Pettifor, A., MacPhail, C., Twine, R., Maman, S., Peacock, D., Kahn, K., & Lippman, S. A. (2017). Gender, HIV testing and stigma: The association of HIV testing behaviors and community-level and individual-level stigma in rural South Africa differ for men and women. AIDS and Behavior, 21(9), 2579–2588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1671-8.

UNFPA. (2015). Emerging evidence, lessons and practice comprehensive sexuality education: A global review. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/CSE_Global_Review_2015.pdf

van Heerden, A., Barnabas, R. V., Norris, S. A., Micklesfield, L. K., van Rooyen, H., & Celum, C. (2017). High prevalence of HIV and non-communicable disease (NCD) risk factors in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(2), e25012. https://doi.org/10.1002/JIA2.25012.

White, D., & Stephenson, R. (2016). Correlates of perceived HIV prevalence and associations with HIV testing behavior among men who have sex with men in the United States. American Journal of Men’s Health, 10(2), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988314556672.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). South Africa - HIV Country Profile 2019. https://cfs.hivci.org/country-factsheet.html

Acknowledgements

We would like to show our gratitude to all fieldworkers involved, the community of Agincourt sub-district and the participants for their hard work and dedication and making this study possible.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Aging at the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers 1P01AG041710-01A1, HAALSI—Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa). The HAALSI cohort is situated in the Agincourt Health and Socio-demographic Surveillance System (HDSS), hosted by the MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit, which is funded by the University of the Witwatersrand and Medical Research Council, South Africa, and the Wellcome Trust, UK (058893/Z/99/A; 069683/Z/02/Z; 085477/Z/08/Z; 085477/B/08/Z). Jennifer Manne-Goehler was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32AI007433 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. The content of this study is the responsibility of the authors and does not imply official perspectives of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LM, XG and TB participated in the data collection. The study design was formed by JMG, TB, KK, ST, and LB. EVE performed the data analyses. EVE and JMG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RDV, LM, TB, XG, KK, ST, and LB have contributed to revision of the manuscript. All authors read the final manuscript and gave their approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval of the HAALSI study was received from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Office of Human Research Administration and the Mpumalanga Provincial Research and Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Empel, E., de Vlieg, R.A., Montana, L. et al. Older Adults Vastly Overestimate Both HIV Acquisition Risk and HIV Prevalence in Rural South Africa. Arch Sex Behav 50, 3257–3276 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-01982-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-01982-1