Abstract

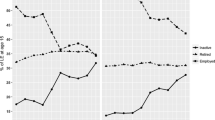

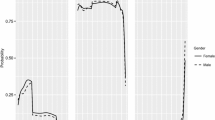

In this paper, we measure the number of years that men and women have been expected to spend in the labour market at age 16 and at age 50 during the period 1986–2016. The objective is twofold. First, we show the change in active years during these three decades, and calculate the gender gap in the time spent in different work statutes (active/inactive, employed/unemployed). Second, we examine the increased prevalence of precarious employment conditions over time. Precarious work is measured through a multidimensional indicator using the Spanish Labour Force Survey. We combined this dataset with registered population data to calculate life expectancy in the labour market, and found that the gender gap in employment has largely reduced due to women’s increased activity. Women have gained 13.6 years of employment during the period considered here, while men lost almost 5 years. In addition, precarious forms of working lives have been growing extensively, and have especially affected younger cohorts, drawing a clear trend towards a dual labour market. In addition, women have spent more time in precarious employment than men at all ages, indicating that most of the growth in females’ employment has been under precarious job conditions.

Source: LFS-INE 1986–2016

Source: SLFS, 2nd Quarters and INE 1986–2016

Source: SLFS, 2nd Quarters and INE 1986–2016

Source: SLFS, 2nd Quarters and INE 1986–2016

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Second quarter were selected because they tend to be less affected by seasoning employment. In addition, past studies have followed this strategy, and it allowed us the comparison of results. For example, Stanek and Requena (2018).

The loss of 9543 cases is mainly due to the exclusion of those who reported being in the military service during the week of the interview. Compulsory military service was abolished in 2001. These cases are distributed across the years in the following way: during the period 1986–1989, the percentage was 30.6 out of the 100% cases that were in military services throughout the whole period studied, then turned to 59.2 during the 90s, and finally in 2000 the percentage was 0.8. The reason to exclude these cases lie in the fact that respondents were not later asked about employment conditions.

We assigned 0.5 to these cases, rather than 0, because part-time jobs imply lower wages than full-time.

We also tested the reliability of the indicator using Cronbach’s alpha. We performed it for every year, and it was steady around 0.6.

The early 1990s recession affecting much of the Western world hit Spain in 1993. Unemployment went down from 16 to 24%. In 1995, signs of recovering were recorded and by 1997 the economy started to grow again.

References

Addabbo, T., Rodríguez-Modroño, P., & Gálvez, L. (2015). Young people living as couples. How women’s labour supply is adapting to the crisis. Spain as a case study. Economic System, 39(1), 27–42.

Alba-Ramírez, A. (1998). How temporary is temporary employment in Spain? Journal of Labour Research, 19(4), 695–710.

Alonso, M., Furió, E. (2007). El papel de la mujer en la sociedad española. Universidad de Valencia, Economía Aplicada—Economia, treball i territori, 19.

Arranz, J. M., García-Serrano, C., & Hernanz, V. (2018). Employment quality: Are there differences by types of contract? Social Indicators Research, 137(1), 203–230.

Banyuls, J., & Recio, A. (2012). The nightmare of the Mediterranean liberalism. In S. Lehndorff (Ed.), The triumph of failed ideas. European models of capitalism in the crisis (pp. 199–217). Brussels: ETUI.

Benach, J., Vives, A., Amable, M., Vanroelen, C., Tarafa, G., & Muntaner, C. (2014). Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 229–253.

Campillo-Poza, I. (2014). Desarrollo y crisis de las políticas de conciliación de la vida laboral y familiar en España (1997–2014): Un marco explicativo. Investigaciones Feministas, 5, 207–231.

Carballo-Cruz, F. (2011). Causes and consequences of the Spanish economic crisis: Why the recovery is taken so long? Panoeconomicus, 3, 309–328.

Carmona, M., Congregado, E., Golpe, A. A., & Iglesias, J. (2016). Self-employment and business cycles: searching for asymmetries in a panel of 23 OECD countries. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 17(6), 1155–1171.

Congregado, E., Golpe, A. A., & Carmona, M. (2010). Is it a good policy to promote self-employment for job creation? Evidence from Spain. Journal of Policy Modeling, 32(6), 828–842.

De Hénau, J., Meulders, S., & O’Dorchai, S. (2010). Maybe baby: Comparing partnered women’s employment and child policies in the EU-15. Feminist Economics, 16(1), 43–77.

De la Rica, S., & Girjón, L. (2016). The impact of family-friendly policies in Spain and their use throughout the business cycle. IZA Journal of European Labour Studies, 5(9), 1–26.

Dolado, J. J., García-Serrano, C., & Jimeno, J. F. (2002). Drawing lessons from the boom of temporary jobs in Spain. The Economic Journal, 112, 270–295.

Domènech, R., García, J. R., Ulloa, C. (2016). The effects of wage flexibility on activity and employment in the Spanish economy. In BBVA Research Working Paper 16/17.

Domínguez-Folgueras, M. (2015). Parenthood and domestic division of labour in Spain, 2002–2010. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 149, 45–64.

Dudel, C., López Gómez, M. A., Benavides, F. G., & Myrskylä, M. (2018). The length of working life in Spain: Levels, recent trends, and the impact of the financial crisis. European Journal of Population, 34(5), 769–791.

Dudel, C., Myrskylä, M. (2016). Recent trends in US working life expectancy by sex, education and race, and the impact of the Great Recession. In MPIDR Working Paper WP-2016-06.

Duell, N. (2004). Defining and assessing precarious employment in Europe: a review of main studies and surveys. In ECONOMIX working paper, Munich.

Flaquer, L., & Escobedo, A. (2014). Licencias parentales y política social de la paternidad en España. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, 32(1), 69–99.

Gallie, D., Felstead, A., Green, F., & Inanc, H. (2017). The hidden face of job insecurity. Work, Employment and Society, 31(1), 36–53.

Garcia-Roman, J., & Cortina, C. (2015). Family type of couples with children: shortening gender differences in parenting? Review of Economics of the Household, 14(4), 921–940.

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., & Sevilla, A. (2014). Total work time in Spain: Evidence from time diary data. Applied Economics, 46(16), 1894–1909.

González, M. J. (2006). Balancing employment and family responsibilities in Southern Europe. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales, 5, 189–217.

Gracia, P., Bellani, D. (2010). Las políticas de conciliación en España y sus efectos: un análisis de las desigualdades de género en el trabajo del hogar y el empleo. Estudios de progreso. In Fundación Alternativas, No. 50.

Guardiola, J., & Guillen-Royo, M. (2015). Income, unemployment, higher education and wellbeing in times of economic crisis: Evidence from Granada (Spain). Social Indicators Research, 120(2), 395–409.

Güell, M., & Petrolongo, B. (2007). How binding are legal limits? Transitions from temporary to permanent work in Spain. Labour Economics, 14(2), 153–183.

Hayward, M. D., & Lichter, D. T. (1998). Work time lost to sickness, unemployment and stoppages: Measurement and application. Journal of the Institute of Actuaries, 117, 533–595.

Hitty, H., Valaste, M. (2009). The average length of working life in the European Union. In The Social Insurance Institution, Working paper 1/2009. Finland.

Izquierdo, M., Lacuesta. M. (2007). Wage inequality in Spain—recent developments. In European Central Bank, Working Paper Series (Vol. 781, pp. 1–40, 41).

Jacobs, A. W., & Padavic, I. (2015). Hours, scheduling and flexibility for women in the US low-wage labour force. Gender, Work and Organization, 22(1), 67–86.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 1–22.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2011). Good jobs, bad jobs. The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Keune, M. (2013). Trade union responses to precarious work in seven European countries. International Journal of Labour Research, 5(1), 59–78.

Leinonen, T., Martikainen, P., & Myrskylä, M. (2015). Working life and retirement expectancies at age 50 by social class: Period and cohort trends and projections for Finland. Journal of Gerontology: Series B, 73(2), 302–313.

León, M., & Migliavacca, M. (2013). Italy and Spain: Still the case of familistic welfare models? Population Review. https://doi.org/10.1353/prv.2013.0001.

Loichinger, E., & Weber, D. (2016). Trends in working life expectancy in Europe. Journal of Aging and Health, 28(7), 1194–1213.

Madsen, P., Molina, O., Moller, J., & Lozano, M. (2013). Labour market transitions of Young workers in Nordic and Southern Europe: The role of flexicurity. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 19(3), 325–343.

Mathers, C. D., & Robine, J. M. (1997). How good is Sullivan’s method for monitoring changes in population health expectancies? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 51, 80–86.

Miguélez, F. (2010). La flexibilidad laboral. Trabajo, 13, 17–36.

Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 237–240.

Nurminen, M. (2008). Worklife expectancies of fixed-term Finnish employees in 1997–2006. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 34(2), 83–95.

Nurminen, M., Heathcote, C. R., David, B. A., & Puza, B. D. (2005). Working life expectancies: The case of Finland 1980–2006. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 168, 567–581.

OECD. (2016). Figures on job quality. Retrieved from http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=JOBQ. Accessed 20 Oct 2018.

Polavieja, J. (2003). Temporary contracts and labour market segmentation in Spain: An employment-rent approach. European Sociological Review, 19(5), 217–501.

Polavieja, J. (2005). Flexibility or polarization? Temporary employment and job tasks in Spain. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 233–258.

Rodgers, G., & Rodgers, J. (1989). Precarious jobs in labour market regulation. Geneva: Free University of Brussels, International Labour Office, International Institute of Labour Studies.

Rodríguez-Modroño, P., Matus, M., Gálvez-Muñoz, L. (2016). Female labour force participation, inequality and household well-being in the Second Globalization. The Spanish case. In Working papers in history and economic institutions, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Spain.

Sevilla-Sanz, A., Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., & Fernández, C. (2010). Gender roles and the división of unpaid work in Spanish households. Feminist Economics, 16(4), 137–184.

Siegel, J. S. (2012). The demography and epidemiology of human health and aging. Dordrecht: Springer.

Stanek, M., & Requena, M. (2018). Expected lifetime in different employment statuses: Evidence from the economic boom-and-bust cycle in Spain. Research on Aging. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027518790261.

Sullivan, D. F. (1971). A single index of mortality and morbidity. HSMHA Health Reports, 86, 347–628.

Swider, B. W., Boswell, W. R., & Zimmerman, R. D. (2011). Examining the job search–turnover relationship: The role of embeddedness, job satisfaction, and available alternatives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 432–441.

Vosko, L. F., Zukewich, N., Cranford, C. (2003). Precarious jobs: A new typology of employment. Perspectives, Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 75-001-XIE.

Wall, K., & Escobedo, A. (2013). Parental leave policies, gender equity and family well-being in Europe: A comparative perspective. In A. Moreno-Minguez (Ed.), Family well-being. European perspectives. Social indicators research series. Switzerland: Springer.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from Ramon Areces Foundations and the research project “La sostenibilidad de las pensiones desde una perspectiva demográfica: El aumento de la actividad laboural femenina y la mejora de la relación contribuyentes/pensionistas”; the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness “Juan de la Cierva” Research Grant Programs (JdlC-I-2014-21178 and JdlC-I-2016-30557); and support from the CSO2016-77449-R R+D project; and CERCA Programme Generalitat de Catalunya.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lozano, M., Rentería, E. Work in Transition: Labour Market Life Expectancy and Years Spent in Precarious Employment in Spain 1986–2016. Soc Indic Res 145, 185–200 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02091-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02091-2