Abstract

Currently there are 850,000 people with Alzheimer’s disease in the UK, with an estimated rise to 1.1 million by 2025. Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau in the brain causing a progressive decline in cognitive impairment. Small non-coding microRNA (miRNA) sequences have been found to be deregulated in the peripheral blood of Alzheimer patients. A systematic review was conducted to extract all miRNA found to be significantly deregulated in the peripheral blood. These deregulated miRNAs were cross-referenced against the miRNAs deregulated in the brain at Braak Stage III. This resulted in a panel of 10 miRNAs (hsa-mir-107, hsa-mir-26b, hsa-mir-30e, hsa-mir-34a, hsa-mir-485, hsa-mir200c, hsa-mir-210, hsa-mir-146a, hsa-mir-34c, and hsa-mir-125b) hypothesised to be deregulated early in Alzheimer’s disease, nearly 20 years before the onset of clinical symptoms. After network analysis of the 10 miRNAs, they were found to be associated with the immune system, cell cycle, gene expression, cellular response to stress, neuron growth factor signalling, wnt signalling, cellular senescence, and Rho GTPases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Dementia

Dementia is a common syndrome in people over 65 years of age and is characterised by a progressive decline in memory and other abilities [1]. In 2014, there were 850,000 people living with Alzheimer’s disease in the UK, costing the economy £26.3 billion a year. Due to the ageing population, this is set to rise to over 1.1 million people with Alzheimer’s disease in 2025 [2].

The Prime Ministers Challenge on Dementia 2020, established by the UK Government, found in 2010/11 that only 42% of estimated dementia sufferers in England had a formal diagnosis [3]. In 2016, the diagnosis rate increased to 67% [4]. This has been attributed to an increased public awareness of dementia, a reduction in the stigma associated with dementia, and an increase in dementia research. Due to the nature of dementia, the accuracy of the diagnosis correlates with the severity of the symptoms and varies from 9 to 41% [4]. Onset of dementia can occur 20–30 years before the first symptoms appear [5]; therefore, the earlier a diagnosis can be made, the less developed the degeneration will be, increasing the probability of a successful treatment.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia accounting for 62% of the dementia patients [2] and is characterised by the presence of amyloid plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau in the brain. In 1991, Braak and Braak mapped the movement of both amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylated tau in the brain during the progression of the disease [6]. The movement of amyloid was split into three Stages (A–C) and that of tau into six (I–VI), as shown in Fig. 1.

Amyloid deposits are mainly found in the isocortex of the cerebral cortex. The plaques are not uniform in shape or size and early stage accumulation suffers from inter-individual variation. The amyloid deposition develops before the onset of tau. However, the presence of amyloid does not mean that tau pathology will develop [6]. During Stage A, amyloid is found in the base layer of the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes. In Stage B, amyloid progresses to almost all isocortex areas and during Stage C, amyloid becomes densely packed [6].

Tau Braak Stages correlate with the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. It is estimated that it can take 48 years to develop from Braak Stage I to Braak Stage V in which Alzheimer’s disease symptoms are apparent. A large proportion of that time is when the disease is non-symptomatic as it can take 30 years to progress from Braak Stage I to Stage III [5].

Braak Stages I and II are centred around the transentorhinal region with Stage II being more densely packed with tau pathology than Stage I. At Stage III, the pathology moves into the entorhinal region with low levels of tau seen in CA1 of the hippocampus and no or mild changes present in the isocortex [6]. The hippocampus is responsible for episodic memory, which is memory of autobiographical events [7]. This corresponds with early symptoms seen in Alzheimer’s disease and is defined as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Patients that fit this definition are 3–5 times more likely to develop dementia within 3–5 years [8].

At Stage IV, there is increased pathology in the entorhinal region and CA1 hippocampus. At this stage, there is no detectable brain atrophy, and the pathology does not meet the criteria for neuropathologic diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. At Stage V, tau is found in almost all areas of the hippocampus and isocortex, with the areas becoming severely affected by Stage VI. Involvement of the isocortex corresponds to late Alzheimer’s disease and clinical diagnosis [6].

Alzheimer disease symptoms have been classified by criteria published in 1984 by both the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Group (ADRDG). It concludes that a definitive diagnosis can only be given when histological analysis by biopsy or autopsy has been conducted [1]. If a biopsy cannot be conducted, then a possible or probable diagnosis is given. A probable diagnosis has a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 70%, a possible diagnosis has a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 48% [9]. Sensitivity is the ability to distinguish between normal and Alzheimer’s disease, while specificity is the capability to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from other types of dementia.

Diagnostic Techniques for Alzheimer’s Disease

An ideal diagnostic technique for Alzheimer’s disease would be that which can identify the disease with adequate reliability considerable time before the onset of symptoms for treatments to be effective, and which is minimally invasive, low-cost, and easy to be applied for mass screening. Current diagnostic techniques for Alzheimer’s disease primarily include cognitive testing [10], neuroimaging [11], and biomarker detection [12]. Other more recently reported diagnostic tests include retinal imaging of amyloid beta, structural changes in the retina [13, 14], and alterations in an Alzheimer patient’s sense of smell [15]. Cognitive testing, for example questionnaires like the mini mental state examination (MMSE), is the most commonly used tool to asses a patient’s symptoms for Alzheimer’s disease [16]. Therefore, cognitive testing is unable to diagnose the disease in the pre-symptomatic stage [17]. Neuroimaging diagnosis, for example magnetic resonance imaging, looks for hippocampal atrophy [18]. However, this is an expensive and specialised technique, which is logistically challenging to be used for mass screening.

Detection of biomarkers in patients is heavily reported for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and peripheral blood [references]. Other biological samples, such as urine [19], breath [20], and saliva [21, 22], have the potential for biomarker detection although they are less prominent in the literature.

CSF requires an invasive lumbar puncture procedure under general anaesthetic with common side effects including mild to moderate headache in up to 46% of cases [23,24,25]. The most commonly reported CSF assay looks for a decrease in amyloid-beta 42 and increased levels of total tau and phosphorylated tau. The test’s sensitivity ranges between 68 and 95% and specificity between 83 and 97% [26,27,28,29,30]. To quantify concentrations of amyloid beta and tau, studies use enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Multi-centre studies conducted using ELISAs have demonstrated a large variability in results [31]. Currently, this variation remains too high to establish international cut-off values, which differentiate Alzheimer patients from normal controls [32].

Another approach is to screen for biomarkers in peripheral blood. Blood collection is significantly less invasive than lumbar puncture and routinely conducted. Therefore, detecting biomarkers in peripheral blood is potentially more applicable to mass screening and regular monitoring of disease progression. Several studies have found differences in specific protein and microRNA (miRNA) concentrations between normal and Alzheimer’s disease blood, highlighting its potential as a diagnostic procedure [12, 33,34,35,36]. This review will focus on miRNAs only.

miRNAs

miRNA are small non-coding RNA, normally 22–23 nucleotides, that control gene expression by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) region in messenger RNA (mRNA). Through this, they suppress translation or induce degradation of the target mRNA [37]. miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II/III in the nucleus to large RNA precursors called pri-miRNA. The pri-miRNA is processed by the RNase III enzyme Drosha to be approximately 70 nucleotides in a hairpin structure. The pri-miRNA is then exported to the cytoplasm by exportin 5. After subsequent processing by the RNase III enzyme Dicer, it releases a small RNA duplex which is then loaded into an Argonaute (Ago) protein. The mature miRNA then directs the Ago-miRNA complex to the target mRNA (Fig. 2) [37,38,39]. The Ago-miRNA complex is very stable in body fluids, and miRNA can be attributed to specific organs and pathologies, making miRNA an ideal biomarker target [40].

miRNA Implicated in Alzheimer’s Disease

The literature includes a number of recent studies reporting miRNAs in blood, CSF, or brain as candidate biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease [references]. Besides variations in the quantification methods and protocols used, the comparability of these studies is particularly challenged due to discrepancies in the stage of Alzheimer’s disease for patients included in the studies. In view of this challenge, the objective of this review was to identify the miRNAs that are deregulated in peripheral blood in late Alzheimer’s and compare them with those found altered in the brain during an early stage of the disease (Braak Stage III). Correlation of deregulated blood-based miRNAs in peripheral blood with those altered in Braak Stage III will allow nearly a 20-year window for screening of patients at risk of Alzheimer’s before the onset of pathological symptoms (Fig. 1).

To establish the number of miRNA found to be significantly deregulated in Alzheimer’s patients, keywords were placed in search databases including Web of Science, Google Scholar, and PubMed. Keywords chosen were “miRNA,” “Alzheimer,” “diagnosis,” and “biomarker” with either “blood,” “serum,” “plasma,” “cerebrospinal fluid,” or “brain.” Both the article title and abstract were assessed for applicability into the review. Last searches were conducted in October 2017. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for the systematic review. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

1.

All samples tested were human

-

2.

Aged matched controls were used

-

3.

Articles were in English

-

4.

A sample group of three or more.

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Review articles, conference abstracts, and studies without a complete set of data.

-

2.

Articles that do not mention Alzheimer’s or dementia in the title or abstract.

The following information was then extracted from the selected articles: Fist named author, year of publication, participant country, blood sample type used, number of control participants, number of Alzheimer patients, any other participant group used, Alzheimer’s disease diagnostic technique, and the significantly deregulated miRNA.

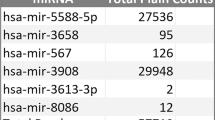

miRNA Deregulation in Blood

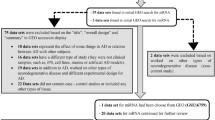

From the systematic review, 20 articles were found to look at miRNA blood deregulation in Alzheimer patients. Nineteen articles were published between 2012 and 2016 and one in 2007 are summarised in Table 1.

From the 20 articles, 102 miRNAs were found to be deregulated in Alzheimer patient’s blood compared to aged matched controls [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Ten articles looked at serum blood samples [44,45,46,47, 50, 55, 57,58,59,60], 4 at plasma [48, 50, 51, 61], 3 at blood mononuclear cells (BMC) [43, 52, 62], 2 in exosomes [42, 49], and 1 in whole blood [41]. This corresponded to 56 miRNAs found to be deregulated in serum, 10 in plasma, 11 in whole blood, 10 in BMC, and 15 in exosomes as shown in Table 2. The highest fold changes were seen in the plasma.

Twelve articles in the systematic review used the MMSE to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, 10 gave an MMSE score with the standard deviation. The numbers were extracted and compiled into the plot in Fig. 3, which shows a decreasing progression of MMSE scores from MCI at 21 to severe cognitive impairment at 10.

Forest plot showing the distribution of MMSE scores from 10 articles. Study ID: (1) Kiko (2014) [51], (2) Cheng (2014) [42], (3) Leidinger (2013) [41], (4) Zhu (2014) [59], (5) Kumar (2013) [48], (6) Geekiyanage (2012) [56], (7) Wang (2015) [61], (8) Tan (2014) [47], (9) Dong (2015) [57], and (10) Tan (2014) [44]

Eight miRNAs have been found to be significantly deregulated when comparing both control and MCI, and control and Alzheimer’s disease candidates. Two miRNAs are significantly different between MCI and Alzheimer’s disease (193b and 200b) [49, 55]. However, the presence of MCI does not guarantee an Alzheimer disease diagnosis; therefore, the miRNA specific to MCI that develops into Alzheimer’s disease must be extracted.

Four miRNAs were found to be significantly deregulated in two different articles (Table 3). However, only two were consistent between articles (125b and181c) and two were inconsistent (9 and 135a-5p). Both mir-9 and mir-181c have MMSE scores assigned to the two articles, the first article has an MMSE score of 10.5 and the second 15.

Sensitivity and specificity values were extracted from nine articles and are shown in Table 4.

A further literature study was conducted to establish the role of each blood deregulated miRNA. This is to determine whether the miRNA in the blood are predominately associated with inflammation, amyloid-beta, or tau signalling pathways. Results in Fig. 4 show that 44 miRNAs have unknown targets, 14 from amyloid, 10 from inflammation, 7 from apoptosis, 3 from tau, and 13 from other signalling pathways.

MiRNA Deregulated in the CSF

Twelve articles were found to contain data for deregulation of miRNA in the CSF; this resulted in 153 deregulated miRNAs. Nineteen miRNAs were found to be deregulated between more than one article; all but 6 had consistent results.

A recent multi-centre study looking at the deregulation of 4 miRNAs in the CSF of Alzheimer patients and found significant differences between results from the three centres [63]. All centres used PCR for analysis and the same RNA isolation procedure. After analysis, the multi-centre study found a significant difference between centrifuged and non-centrifuged samples before freezing and correlations between the PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values and storage time. This highlights the need for detailed standardised procedures.

miRNA Deregulation in the Brain

Twenty-seven articles were found looking at deregulated miRNA in the brain, corresponding to 250 miRNAs. The search included 13 articles from the temporal cortex [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], 6 from the hippocampus [65, 77,78,79,80,81], 8 from the frontal cortex [77, 78, 82,83,84,85,86,87], 1 from the entorhinal region [81], and 1 the parietal lobe [88].

Articles that define the Braak Stage were extracted and split into three groups, Braak Stage I-II, Braak Stage III-IV, and Braak Stage V-VI. Braak Stages I and II are generally used as control cases, 27 miRNAs were deregulated at Braak III–IV and 99 at Braak V–VI, as shown in Fig. 5. Five hundred millilitres of CSF can be absorbed into the blood daily, and damage to the blood brain barrier during Alzheimer’s disease enables exchange of miRNA between the brain and peripheral blood [89]. Therefore, miRNAs deregulated in the blood were cross-referenced against those deregulated at Braak Stage III.

miRNA Deregulated in the Brain and Blood

All deregulated miRNAs in the peripheral blood were cross-referenced against the miRNA deregulated in the brain. Forty-seven miRNAs are deregulated in both the brain and peripheral blood, 30 of these could be assigned a Braak Stage. From the 30 miRNAs, 10 were found to be deregulated at Braak Stage III; these miRNA are shown in Table 5.

Among these, 10 miRNAs that were deregulated both in the brain Braak Stage III and in peripheral blood; 4 miRNAs, namely mir-26b, mir-34a, mir-146a, and mir-125b, were found to be differently deregulated in the two tissues, i.e. upregulated in the brain but downregulated in blood. However, mir-34a was reported to be upregulated in blood mononuclear cells in a study (current reference [52] i.e. Schipper et al).

Network Analysis of Deregulated miRNA at Braak Stage III in the Brain and Peripheral Blood

The 10 miRNAs found to be deregulated at Braak Stage III and in the blood (Table 5) were imputed into the mirnet online software [91]. Seven of the 10 miRNAs, namely mir-107, mir-26b, mir-30e, mir-34a, mir-210, mir-146a, and mir-125b, resulted in Alzheimer’s disease as at least one of their target diseases from the software analysis. Interestingly, out of these 7 miRNAs that targeted Alzheimer’s disease, 3 miRNAs, namely mir-107, mir-30e, and mir-210, were found to be similarly deregulated in the brain and peripheral blood according to Table 5.

The mirnet online software was also employed to analyse the target genes for the 10 miRNAs listed in Table 5. The resulting network diagram, shown in Fig. 6, resulted in 5173 targets associated with the 10 miRNAs. A reactome analysis was conducted using the mirnet software to determine the roles of the target genes. Only statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) groups were then extracted from mirnet. The statistically significant groups with more than 85 target genes are shown in Fig. 7.

Network diagram extracted from mirnet [91] miRNA’s ( ) targets (

) targets ( )

)

Roles of targets found in network analysis (Fig. 6)

Eight different groups are outlined in Fig. 7: immune system (716 targets), cell cycle (469 targets), Rho GTPases (212 targets), gene expression (295 genes), cellular response to stress (130 targets), nerve growth factors (NGF) signalling (100 targets), Wnt signalling (90 targets), and cellular senescence (87 genes).

Chronic inflammation is well reported in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease leading to oxidative stress. Because of this, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant agents are being investigated as a disease-modifying therapy [92,93,94]. Both mir-125b and mir-146a have been connected to neuroinflammation, and they are significantly upregulated by NF-kB, a pro-inflammatory transcription factor [95].

Abnormal expression of cell-cycle proteins have been found in neurons; generally, neurons are post-mitotic [96]. mir-26b has been implicated in cell-cycle regulation through Rb1/E2F and p27/kip1 [69], mir-107 regulates CDK6 [97], and mir-125b can downregulate the cell-cycle inhibitor CDKN2A [98]. mir-34a has also been found to be important in the regulation of the neuronal cell cycle and apoptosis [99].

Rho and its effectors have been linked to amyloid-beta production, as inhibition of Rho-associated kinase was found to reduce cortical amyloid-beta 42 by 33% in mice [100]. Amyloid beta has been found to target Rho GTPases, which may result in changes in the actin cytoskeleton [101]. mir-34a can repress expression of RhoA [102], which is reduced in the post-mortem Alzheimer disease brain [103].

Altered gene expression in the brain between aged control and Alzheimer patients has been documented [104,105,106].

The increased oxidative stress in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease induces a stress response in the cells, for example the release of IL-6, which is altered in the brain of Alzheimer patients [107]. Cell culture models using neurones have found an upregulation in mir-210 and mir-146a in response to increased ROS [108, 109].

There is a moderate increase in NGF in all brain regions except for the nucleus basalis in Alzheimer’s disease [110]. NGF is a protein, which promotes the growth and survival of cholinergic neurons, which degenerate in the nucleus basalis during Alzheimer’s disease [111]. However, this is not an early pathological event in Alzheimer’s disease as cholinergic neurons in early Alzheimer’s disease (mild cognitive impairment) show no significant difference to patients with no cognitive impairment [112]. Decreased expression of mir-210 has also been found in response to NGF treatment [113].

Various Wnt signalling components are altered in Alzheimer’s disease, for example Dkk1 is increased in the Alzheimer disease brain and is implicated in tau phosphorylation. Some studies have also shown Wnt signalling to be neuroprotective [114, 115]. Mir-107 has been shown to regulate Dkk1; however, this was in osteosarcoma [116].

The presence of cellular stress can induce senescence. Cell culture models have shown that amyloid beta can accelerate cellular senescence [117] and there is an increased number of senescent astrocytes in the brain [118]. mir-125b is a negative regulator of p53 in humans [119]. p53 is implicated in cell-cycle control, apoptosis, DNA, and cellular stress and contributes to cellular senescence [120].

Conclusion

The review outlines an alternative approach to finding early miRNA biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. It utilises miRNA deregulated in the blood during late Alzheimer’s disease and compares to miRNA found to be altered in the brain during early Alzheimer’s disease. However, the literature is riddled with inconsistency. This could stem from technical variations or from limitations in comparability due to differences in a patient’s stage of Alzheimer’s disease (Fig. 3). To improve comparability, Alzheimer patients could be grouped into Braak Stages, and direct comparisons could be made between their pathology and miRNA profile in peripheral blood. Multi-centre comparisons would also benefit from having a standardised analytical protocol, storage time, and quantification method. The review also highlights the possibility of using miRNA deregulated in post-mortem brain samples to identify potential biomarker targets, which is possible due to the higher stability of the miRNAs compared to that of mRNA.

References

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34(7):939–944

Anna Dowrick AS (2014) Dementia 2014 opportunity for change report. A.s. Society, Editor

Team, O.P.a.D., Prime minister’s challenge on dementia, D.o. Health, Editor. 2012.

Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H (2009) Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23(4):306–314

Ohm TG, Müller H, Braak H, Bohl J (1995) Close-meshed prevalence rates of different stages as a tool to uncover the rate of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neuroscience 64(1):209–217

Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82(4):239–259

Tulving E, Markowitsch HJ (1998) Episodic and declarative memory: role of the hippocampus. Hippocampus 8(3):198–204

Borroni B, Di Luca M, Padovani A (2006) Predicting Alzheimer dementia in mild cognitive impairment patients. Are biomarkers useful? Eur J Pharmacol 545(1):73–80

Knopman DS et al (2001) Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 56(9):1143–1153

Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ (1992) The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 40(9):922–935

Delacourte A, David JP, Sergeant N, Buee L, Wattez A, Vermersch P, Ghozali F, Fallet-Bianco C et al (1999) The biochemical pathway of neurofibrillary degeneration in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 52(6):1158–1165

Wang T, Xiao S, Liu Y, Lin Z, Su N, Li X, Li G, Zhang M et al (2014) The efficacy of plasma biomarkers in early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 29(7):713–719

Cheung CY, Ong YT, Ikram MK, Ong SY, Li X, Hilal S, Catindig JAS, Venketasubramanian N et al (2014) Microvascular network alterations in the retina of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10(2):135–142

Koronyo Y, Salumbides BC, Black KL, Koronyo-Hamaoui M (2012) Alzheimer’s disease in the retina: imaging retinal abeta plaques for early diagnosis and therapy assessment. Neurodegener Dis 10(1–4):285–293

Velayudhan L, Gasper A, Pritchard M, Baillon S, Messer C, Proitsi P (2015) Pattern of smell identification impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 46(2):381–387

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198

McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hébert R (1997) Community screening for dementia: the mini mental state exam (MMSE) and modified mini-mental state exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol 50(4):377–383

Burton EJ, Barber R, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Robson J, Perry RH, Jaros E, Kalaria RN, O’Brien JT (2009) Medial temporal lobe atrophy on MRI differentiates Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies and vascular cognitive impairment: a prospective study with pathological verification of diagnosis. Brain 132(Pt 1):195–203

Cheng L, Sun X, Scicluna BJ, Coleman BM, Hill AF (2014) Characterization and deep sequencing analysis of exosomal and non-exosomal miRNA in human urine. Kidney Int 86(2):433–444

Pinkerton M, Chinchilli V, Banta E, Craig T, August A, Bascom R, Cantorna M, Harvill E et al (2013) Differential expression of microRNAs in exhaled breath condensates of patients with asthma, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and healthy adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132(1):217–219

Gallo A, Tandon M, Alevizos I, Illei GG (2012) The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS One 7(3):e30679

Majem B, Rigau M, Reventós J, Wong D (2015) Non-coding RNAs in saliva: emerging biomarkers for molecular diagnostics. Int J Mol Sci 16(4):8676–8698

Monserrate AE, Ryman DC, Ma S, Xiong C, Noble JM, Ringman JM, Morris JC, Danek A et al (2015) Factors associated with the onset and persistence of post-lumbar puncture headache. JAMA Neurol 72(3):325–332

Vilming ST, Kloster R, Sandvik L (2001) The importance of sex, age, needle size, height and body mass index in post-lumbar puncture headache. Cephalalgia 21(7):738–743

Peskind E, Nordberg A, Darreh-Shori T, Soininen H (2009) Safety of lumbar puncture procedures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 6(3):290–292

Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L (2006) Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Lancet Neurol 5(3):228–234

Zetterberg H, Wahlund LO, Blennow K (2003) Cerebrospinal fluid markers for prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett 352(1):67–69

Buchhave P et al (2012) Cerebrospinal fluid levels of beta-amyloid 1-42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(1):98–106

Snider BJ, Fagan AM, Roe C, Shah AR, Grant EA, Xiong C, Morris JC, Holtzman DM (2009) Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and rate of cognitive decline in very mild dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Arch Neurol 66(5):638–645

Mulder C, Verwey NA, van der Flier WM, Bouwman FH, Kok A, van Elk EJ, Scheltens P, Blankenstein MA (2010) Amyloid-beta(1-42), total tau, and phosphorylated tau as cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Clin Chem 56(2):248–253

Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Persson S, Arai H, Batish SD, Bernardini S, Bocchio-Chiavetto L, Blankenstein MA et al (2011) The Alzheimer’s Association external quality control program for cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement 7(4):386–395 e6

Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Persson S, Carrillo MC, Collins S, Chalbot S, Cutler N, Dufour-Rainfray D et al (2013) CSF biomarker variability in the Alzheimer’s Association quality control program. Alzheimers Dement 9(3):251–261

Hye A, Riddoch-Contreras J, Baird AL, Ashton NJ, Bazenet C, Leung R, Westman E, Simmons A et al (2014) Plasma proteins predict conversion to dementia from prodromal disease. Alzheimers Dement 10(6):799–807 e2

Decourt B et al (2013) Can platelet BACE1 levels be used as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease? Proof-of-concept study. Platelets 24(3):235–238

Doecke JD et al (2012) Blood-based protein biomarkers for diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 69(10):1318–1325

Ewers, M., et al., CSF biomarkers for the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. A large-scale international multicenter study. Alzheimers Dement, 2015.

Ha M, Kim VN (2014) Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15(8):509–524

Kobayashi H, Tomari Y (2015) RISC assembly: coordination between small RNAs and Argonaute proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta

Hammond SM (2015) An overview of microRNAs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 87:3–14

Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B (2011) Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 39(16):7223–7233

Leidinger P et al (2013) A blood based 12-miRNA signature of Alzheimer disease patients. Genome Biol 14(7)

Cheng L et al (2014) Prognostic serum miRNA biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease shows concordance with neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessment. Mol Psychiatry

Bhatnagar S et al (2014) Increased microRNA-34c abundance in Alzheimer’s disease circulating blood plasma. Front Mol Neurosci 7:2

Tan L, Yu JT, Liu QY, Tan MS, Zhang W, Hu N, Wang YL, Sun L et al (2014) Circulating miR-125b as a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci 336(1–2):52–56

Galimberti D, Villa C, Fenoglio C, Serpente M, Ghezzi L, Cioffi SMG, Arighi A, Fumagalli G et al (2014) Circulating miRNAs as potential biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 42(4):1261–1267

Burgos K, Malenica I, Metpally R, Courtright A, Rakela B, Beach T, Shill H, Adler C et al (2014) Profiles of extracellular miRNA in cerebrospinal fluid and serum from patients with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases correlate with disease status and features of pathology. PLoS One 9(5):e94839

Tan L, Yu JT, Tan MS, Liu QY, Wang HF, Zhang W, Jiang T, Tan L (2014) Genome-wide serum microRNA expression profiling identifies serum biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 40(4):1017–1027

Kumar P, Dezso Z, MacKenzie C, Oestreicher J, Agoulnik S, Byrne M, Bernier F, Yanagimachi M et al (2013) Circulating miRNA biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 8(7):e69807

Liu CG et al (2014) MicroRNA-193b is a regulator of amyloid precursor protein in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid derived exosomal microRNA-193b is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Med Rep 10(5):2395–2400

Liu C-G et al (2014) MicroRNA-384 regulates both amyloid precursor protein and beta-secretase expression and is a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Med 34(1):160–166

Kiko T, Nakagawa K, Tsuduki T, Furukawa K, Arai H, Miyazawa T (2014) MicroRNAs in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid as potential markers for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 39(2):253–259

Schipper HM, Maes OC, Chertkow HM, Wang E (2007) MicroRNA expression in Alzheimer blood mononuclear cells. Gene Regul Syst Bio 1:263–274

Bekris LM, Lutz F, Montine TJ, Yu CE, Tsuang D, Peskind ER, Leverenz JB (2013) MicroRNA in Alzheimer’s disease: an exploratory study in brain, cerebrospinal fluid and plasma. Biomarkers 18(5):455–466

Sheinerman KS, Tsivinsky VG, Abdullah L, Crawford F, Umansky SR (2013) Plasma microRNA biomarkers for detection of mild cognitive impairment: biomarker validation study. Aging (Albany NY) 5(12):925–938

Liu CG, Wang JL, Li L, Xue LX, Zhang YQ, Wang PC (2014) MicroRNA-135a and -200b, potential biomarkers for Alzheimers disease, regulate beta secretase and amyloid precursor protein. Brain Res 1583:55–64

Geekiyanage H, Jicha GA, Nelson PT, Chan C (2012) Blood serum miRNA: non-invasive biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol 235(2):491–496

Dong H et al (2015) Serum microRNA profiles serve as novel biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Dis Markers 2015:625659

Geekiyanage H, Chan C (2011) MicroRNA-137/181c regulates serine palmitoyltransferase and in turn amyloid beta, novel targets in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 31(41):14820–14830

Zhu Y et al (2015) Quantification of microRNA-210 in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Ther Med 9(3):1013–1017

Jia LH, Liu YN (2016) Downregulated serum miR-223 servers as biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Biochem Funct 34(4):233–237

Wang T, Chen K, Li H, Dong S, Su N, Liu Y, Cheng Y, Dai J et al (2015) The feasibility of utilizing plasma MiRNA107 and BACE1 messenger RNA gene expression for clinical diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Psychiatry 76(2):135–141

Villa C, Ridolfi E, Fenoglio C, Ghezzi L, Vimercati R, Clerici F, Marcone A, Gallone S et al (2013) Expression of the transcription factor Sp1 and its regulatory hsa-miR-29b in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 35(3):487–494

Muller M et al (2016) Validation of microRNAs in cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers for different forms of dementia in a multicenter study. J Alzheimers Dis 52(4):1321–1333

Wang WX, Huang Q, Hu Y, Stromberg AJ, Nelson PT (2011) Patterns of microRNA expression in normal and early Alzheimer’s disease human temporal cortex: white matter versus gray matter. Acta Neuropathol 121(2):193–205

Lukiw WJ, Zhao Y, Cui JG (2008) An NF-kappaB-sensitive micro RNA-146a-mediated inflammatory circuit in Alzheimer disease and in stressed human brain cells. J Biol Chem 283(46):31315–31322

Wang WX, Rajeev BW, Stromberg AJ, Ren N, Tang G, Huang Q, Rigoutsos I, Nelson PT (2008) The expression of microRNA miR-107 decreases early in Alzheimer’s disease and may accelerate disease progression through regulation of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. J Neurosci 28(5):1213–1223

Hebert SS, Horre K, Nicolai L, Papadopoulou AS, Mandemakers W, Silahtaroglu AN, Kauppinen S, Delacourte A et al (2008) Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(17):6415–6420

Hebert SS et al (2009) MicroRNA regulation of Alzheimer’s Amyloid precursor protein expression. Neurobiol Dis 33(3):422–428

Absalon S, Kochanek DM, Raghavan V, Krichevsky AM (2013) MiR-26b, upregulated in Alzheimer’s disease, activates cell cycle entry, tau-phosphorylation, and apoptosis in postmitotic neurons. J Neurosci 33(37):14645–14659

Wong HK et al (2013) De-repression of FOXO3a death axis by microRNA-132 and -212 causes neuronal apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 22(15):3077–3092

Cui JG, Li YY, Zhao Y, Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ (2010) Differential regulation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 (IRAK-1) and IRAK-2 by microRNA-146a and NF-kappaB in stressed human astroglial cells and in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 285(50):38951–38960

Sethi P, Lukiw WJ (2009) Micro-RNA abundance and stability in human brain: specific alterations in Alzheimer’s disease temporal lobe neocortex. Neurosci Lett 459(2):100–104

Hebert SS et al (2010) Genetic ablation of Dicer in adult forebrain neurons results in abnormal tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet 19(20):3959–3969

Smith P, al Hashimi A, Girard J, Delay C, Hébert SS (2011) In vivo regulation of amyloid precursor protein neuronal splicing by microRNAs. J Neurochem 116(2):240–247

Hebert SS et al (2013) A study of small RNAs from cerebral neocortex of pathology-verified Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with lewy bodies, hippocampal sclerosis, frontotemporal lobar dementia, and non-demented human controls. J Alzheimers Dis 35(2):335–348

Sarkar S, Jun S, Rellick S, Quintana DD, Cavendish JZ, Simpkins JW (2016) Expression of microRNA-34a in Alzheimer’s disease brain targets genes linked to synaptic plasticity, energy metabolism, and resting state network activity. Brain Res 1646:139–151

Lau P, Bossers K, Janky R', Salta E, Frigerio CS, Barbash S, Rothman R, Sierksma ASR et al (2013) Alteration of the microRNA network during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med 5(10):1613–1634

Cogswell JP, Ward J, Taylor IA, Waters M, Shi Y, Cannon B, Kelnar K, Kemppainen J et al (2008) Identification of miRNA changes in Alzheimer’s disease brain and CSF yields putative biomarkers and insights into disease pathways. J Alzheimers Dis 14(1):27–41

Lukiw WJ (2007) Micro-RNA speciation in fetal, adult and Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Neuroreport 18(3):297–300

Muller M et al (2014) MicroRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease: differential expression in hippocampus and cell-free cerebrospinal fluid. Neurobiol Aging 35(1):152–158

Faghihi MA, Zhang M, Huang J, Modarresi F, van der Brug MP, Nalls MA, Cookson MR, St-Laurent G et al (2010) Evidence for natural antisense transcript-mediated inhibition of microRNA function. Genome Biol 11(5):R56

Shioya M, Obayashi S, Tabunoki H, Arima K, Saito Y, Ishida T, Satoh J (2010) Aberrant microRNA expression in the brains of neurodegenerative diseases: miR-29a decreased in Alzheimer disease brains targets neurone navigator 3. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 36(4):320–330

Banzhaf-Strathmann J, Benito E, May S, Arzberger T, Tahirovic S, Kretzschmar H, Fischer A, Edbauer D (2014) MicroRNA-125b induces tau hyperphosphorylation and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO J 33(15):1667–1680

Long JM, Ray B, Lahiri DK (2014) MicroRNA-339-5p down-regulates protein expression of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) in human primary brain cultures and is reduced in brain tissue specimens of Alzheimer disease subjects. J Biol Chem 289(8):5184–5198

Long JM, Ray B, Lahiri DK (2012) MicroRNA-153 physiologically inhibits expression of amyloid-beta precursor protein in cultured human fetal brain cells and is dysregulated in a subset of Alzheimer disease patients. J Biol Chem 287(37):31298–31310

Santa-Maria I, Alaniz ME, Renwick N, Cela C, Fulga TA, van Vactor D, Tuschl T, Clark LN et al (2015) Dysregulation of microRNA-219 promotes neurodegeneration through post-transcriptional regulation of tau. J Clin Invest 125(2):681–686

Lei X, Lei L, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Cheng Y (2015) Downregulated miR-29c correlates with increased BACE1 expression in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8(2):1565–1574

Nunez-Iglesias J, Liu CC, Morgan TE, Finch CE, Zhou XJ (2010) Joint genome-wide profiling of miRNA and mRNA expression in Alzheimer’s disease cortex reveals altered miRNA regulation. PLoS One 5(2):e8898

Zipser BD, Johanson CE, Gonzalez L, Berzin TM, Tavares R, Hulette CM, Vitek MP, Hovanesian V et al (2007) Microvascular injury and blood-brain barrier leakage in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 28(7):977–986

Wu Q et al (2016) The protective role of microRNA-200c in Alzheimer’s disease pathologies is induced by beta amyloid-triggered endoplasmic reticulum stress. Front Mol Neurosci 9:140

Fan Y, Siklenka K, Arora SK, Ribeiro P, Kimmins S, Xia J (2016) miRNet - dissecting miRNA-target interactions and functional associations through network-based visual analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44(W1):W135–W141

Heneka MT, Carson MJ, Khoury JE, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, Jacobs AH, Wyss-Coray T et al (2015) Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 14(4):388–405

Di Bona D et al (2010) Immune-inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: therapeutic implications. Curr Pharm Des 16(6):684–691

Holmes C, Cunningham C, Zotova E, Woolford J, Dean C, Kerr S, Culliford D, Perry VH (2009) Systemic inflammation and disease progression in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 73(10):768–774

Lukiw WJ, Alexandrov PN (2012) Regulation of complement factor H (CFH) by multiple miRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain. Mol Neurobiol 46(1):11–19

van Leeuwen LA, Hoozemans JJ (2015) Physiological and pathophysiological functions of cell cycle proteins in post-mitotic neurons: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 129(4):511–525

Feng L, Xie Y, Zhang H, Wu Y (2012) miR-107 targets cyclin-dependent kinase 6 expression, induces cell cycle G1 arrest and inhibits invasion in gastric cancer cells. Med Oncol 29(2):856–863

Pogue AI, Cui JG, Li YY, Zhao Y, Culicchia F, Lukiw WJ (2010) Micro RNA-125b (miRNA-125b) function in astrogliosis and glial cell proliferation. Neurosci Lett 476(1):18–22

Modi PK, Jaiswal S, Sharma P (2016) Regulation of neuronal cell cycle and apoptosis by microRNA 34a. Mol Cell Biol 36(1):84–94

Zhou Y, Su Y, Li B, Liu F, Ryder JW, Wu X, Gonzalez-DeWhitt P, Gelfanova V et al (2003) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can lower amyloidogenic Abeta42 by inhibiting Rho. Science 302(5648):1215–1217

Mendoza-Naranjo A, Gonzalez-Billault C, Maccioni RB (2007) Abeta1-42 stimulates actin polymerization in hippocampal neurons through Rac1 and Cdc42 Rho GTPases. J Cell Sci 120(Pt 2):279–288

Yamamura S, Saini S, Majid S, Hirata H, Ueno K, Deng G, Dahiya R (2012) MicroRNA-34a modulates c-Myc transcriptional complexes to suppress malignancy in human prostate cancer cells. PLoS One 7(1):e29722

Huesa G, Baltrons MA, Gómez-Ramos P, Morán A, García A, Hidalgo J, Francés S, Santpere G et al (2010) Altered distribution of RhoA in Alzheimer’s disease and AbetaPP overexpressing mice. J Alzheimers Dis 19(1):37–56

Tan MG, Chua WT, Esiri MM, Smith AD, Vinters HV, Lai MK (2010) Genome wide profiling of altered gene expression in the neocortex of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res 88(6):1157–1169

Sekar S, McDonald J, Cuyugan L, Aldrich J, Kurdoglu A, Adkins J, Serrano G, Beach TG et al (2015) Alzheimer’s disease is associated with altered expression of genes involved in immune response and mitochondrial processes in astrocytes. Neurobiol Aging 36(2):583–591

Colangelo V, Schurr J, Ball MJ, Pelaez RP, Bazan NG, Lukiw WJ (2002) Gene expression profiling of 12633 genes in Alzheimer hippocampal CA1: transcription and neurotrophic factor down-regulation and up-regulation of apoptotic and pro-inflammatory signaling. J Neurosci Res 70(3):462–473

Wang WY et al (2015) Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Transl Med 3(10):136

Li JJ, Dolios G, Wang R, Liao FF (2014) Soluble beta-amyloid peptides, but not insoluble fibrils, have specific effect on neuronal microRNA expression. PLoS One 9(3):e90770

Jiao G et al (2015) MicroRNA-21 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in H(2)O(2)-stimulated rat spinal cord neurons. Mol Med Rep 12(5):7011–7016

Scott SA, Mufson EJ, Weingartner JA, Skau KA, Crutcher KA (1995) Nerve growth factor in Alzheimer’s disease: increased levels throughout the brain coupled with declines in nucleus basalis. J Neurosci 15(9):6213–6221

Mufson EJ, Counts SE, Perez SE, Ginsberg SD (2008) Cholinergic system during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease: therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Neurother 8(11):1703–1718

Gilmor ML, Erickson JD, Varoqui H, Hersh LB, Bennett DA, Cochran EJ, Mufson EJ, Levey AI (1999) Preservation of nucleus basalis neurons containing choline acetyltransferase and the vesicular acetylcholine transporter in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol 411(4):693–704

Hamada N, Fujita Y, Kojima T, Kitamoto A, Akao Y, Nozawa Y, Ito M (2012) MicroRNA expression profiling of NGF-treated PC12 cells revealed a critical role for miR-221 in neuronal differentiation. Neurochem Int 60(8):743–750

De Ferrari GV et al (2003) Activation of Wnt signaling rescues neurodegeneration and behavioral impairments induced by beta-amyloid fibrils. Mol Psychiatry 8(2):195–208

Alvarez AR, Godoy JA, Mullendorff K, Olivares GH, Bronfman M, Inestrosa NC (2004) Wnt-3a overcomes beta-amyloid toxicity in rat hippocampal neurons. Exp Cell Res 297(1):186–196

Zhang ZC, Liu JX, Shao ZW, Pu FF, Wang BC, Wu Q, Zhang YK, Zeng XL et al (2017) In vitro effect of microRNA-107 targeting Dkk-1 by regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in osteosarcoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(27):e7245

He N, Jin WL, Lok KH, Wang Y, Yin M, Wang ZJ (2013) Amyloid-beta(1-42) oligomer accelerates senescence in adult hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells via formylpeptide receptor 2. Cell Death Dis 4:e924

Bhat R, Crowe EP, Bitto A, Moh M, Katsetos CD, Garcia FU, Johnson FB, Trojanowski JQ et al (2012) Astrocyte senescence as a component of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 7(9):e45069

Le MT et al (2009) MicroRNA-125b is a novel negative regulator of p53. Genes Dev 23(7):862–876

Rufini A, Tucci P, Celardo I, Melino G (2013) Senescence and aging: the critical roles of p53. Oncogene 32:5129–5143

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Swarbrick, S., Wragg, N., Ghosh, S. et al. Systematic Review of miRNA as Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurobiol 56, 6156–6167 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-019-1500-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-019-1500-y