Abstract

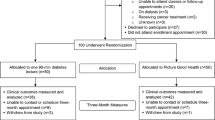

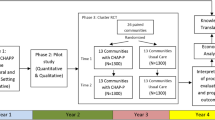

Wide-reaching health promotion interventions are needed in influential, accessible community settings to address African American (AA) diabetes and CVD disparities. Most AAs are overweight/obese, which is a primary clinical risk factor for diabetes/CVD. Using a faith-community-engaged approach, this study examined feasibility and outcomes of Project Faith Influencing Transformation (FIT), a diabetes/CVD screening, prevention, and linkage to care pilot intervention to increase weight loss in AA church-populations at 8 months. Six churches were matched and randomized to multilevel FIT intervention or standard education control arms. Key multilevel religiously tailored FIT intervention components included: (a) individual self-help materials (e.g., risk checklists, pledge cards); (b) YMCA-facilitated weekly group Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) weight loss classes; (c) church service activities (e.g., sermons, responsive readings); and (d) church-community text/voice messages to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Health screenings (e.g., weight, blood pressure, blood glucose) were held during church services to identify participants with diabetes/CVD risks and refer them to their church’s DPP class and linkage to care services. Participants (N = 352 church members and community members using churches’ outreach ministries) were primarily female (67%) and overweight/obese (87%). Overall, FIT intervention participants were significantly more likely to achieve a > 5 lb weight loss (OR = 1.6; CI = 1.24, 2.01) than controls. Odds of intervention FIT-DPP participants achieving a > 5 lb weight loss were 3.6 times more than controls (p < .07). Exposure to sermons, text/email messages, brochures, commitment cards, and posters was significantly related to > 5 lb. weight loss. AA churches can feasibly assist in increasing reach and impact of diabetes/CVD risk reduction interventions with intensive weight loss components among at risk AA church-populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Sec. 2. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl. 1):S13–22.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health disparities and inequalities report – United States 2011. Diabetes — United States, 2006 and 2010. MMWR. 2013;62(Suppl 3):99–104.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). CDC health disparities and inequalities report – United States. Coronary heart disease and stroke deaths — United States, 2009. MMWR. 2011;62(Suppl 3):157–60.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). CDC health disparities and inequalities report – United States. Prevalence of hypertension and controlled hypertension — United States, 2007–2010. MMWR. 2011;62(Suppl 3):144–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). CDC health disparities and inequalities report – United States. Obesity — United States, 1999–2010. MMWR. 2011;62(Suppl 3):120–8.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes--2015: summary of revisions. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl. 1):S4.

American Medical Association. Prevent Diabetes STAT. Retrieved from http://www.ama-assn.org/sub/prevent-diabetes-stat/

CDC. Screen & Refer Patients to a Lifestyle Change Program. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/lifestyle-program/deliverers/index.html

American Medical Association. STAT. Retrieved from http://www.ama-assn.org/sub/prevent-diabetes-stat/

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville; 2016. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf#highlights

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health disparities and inequalities report – United States 2011. Health insurance — United States, 2011. MMWR. 2013;62(03):61–4.

Whitaker KM, Everson-Rose SA, Pankow JS, Rodriguez CJ, Lewis TT, Kershaw KN, et al. Experiences of discrimination and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(4):445–55.

Everson-Rose SA, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, Lewis TT, Kershaw KN, Alonso A, et al. Perceived discrimination and incident cardiovascular events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(3):225–34.

Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38(5):976–93.

Moniruzzaman M, Páez A. Accessibility to transit, by transit, and mode share: application of a logistic model with spatial filters. J Transp Geogr. 2012;24:198–205.

Sanchez TW. Poverty, policy, and public transportation. Transport Res Part A: Policy Pract. 2008;42(5):833–41.

Bader MD, Purciel M, Yousefzadeh P, Neckerman KM. Disparities in neighborhood food environments: implications of measurement strategies. Econ Geogr. 2010;86(4):409–30.

Powell-Wiley TM, Ayers CR, de Lemos JA, Lakoski SG, Vega GL, Grundy S, et al. Relationship between perceptions about neighborhood environment and prevalent obesity: data from the Dallas heart study. Obesity. 2013;21(1):E14–21.

Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The black church and the African American experience. Durham: Duke University Press; 1990.

Pew Research Center. (2015). America’s changing religious landscape. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/files/2015/05/RLS-05-08-full-report.pdf.

Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34.

Le D, Holt CL, Hosack DP, Huang J, Clark EM. Religious participation is associated with increases in religious social support in a national longitudinal study of African Americans. J Relig Health. 2016;55(4):1449–60.

Berkley-Patton J, Bowe Thompson, C, Martinez, DA, Hawes SM, Moore E, Williams E, Wainright C. Examining church capacity to develop and disseminate a religiously appropriate HIV tool kit with African American churches. J Urban Health. 2012;90(3):482-99.

Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl. 1):68–81.

Sattin RW, Williams LB, Dias J, Garvin JT, Marion L, Joshua TV, et al. Community trial of a faith-based lifestyle intervention to prevent diabetes among African-Americans. J Community Health. 2016;41(1):87–96.

Samuel-Hodge CD, Johnson CM, Braxton DF, Lackey M. Effectiveness of diabetes prevention program translations among African Americans. Obes Rev. 2014;1:107–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12211.

Boltri JM, Davis-Smith M, Okosun IS, Seale JP, Foster B. Translation of the National Institutes of Health Diabetes Prevention Program in African American churches. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:194–202.

Dodani S, Fields JZ. Implementation of the fit body and soul, a church-based life style program for diabetes prevention in high risk African Americans: a feasibility study. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:465–72.

Davis-Smith M. Implementing a diabetes prevention program in a rural African-American church. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:440–6.

Faridi Z, Shuval K, Njike VY, Katz JA, Jennings G, Williams M, et al. Partners reducing effects of diabetes (PREDICT): a diabetes prevention physical activity and dietary intervention through African-American churches. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:306–15.

Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;1:10–21.

Berkley-Patton J, Bowe Thompson C, Bradley-Ewing A, Berman M, Booker A, Catley D, Goggin K, Williams E, Wainright C, Rhuland Petty T, Aduloju-Ajijola N. Identifying health conditions, priorities, and relevant multilevel health promotion intervention strategies in African American churches: A faith community health needs assessment. Eval Prog Plan. 2018;31(67):19-28.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403.

Adams R, Hebert CJ, McVey L, Williams R. Implementation of the YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program throughout an integrated health system: a translational study. Perm J. 2016;20(4):82–6. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-241.

Ely E, Graus S, Gregg E, Ali M, Nihm K, Rolka D, et al. A national effort to prevent T2 diabetes: participant level evaluation of CDC’s national prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1331–41.

West DS, Prewitt TE, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity. 2008;16:1413–20.

Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychol Addict Behav. 1996;10(2):90–6.

Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, Umpierrez G, Zimmerman RS, Bailey TS, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology – clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(suppl 1):1–87.

National Cholesterol Education Program. ATP III guidelines at-a-glance quick desk reference. In: National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Bethesda; 2001.

Gross TT, Story CR, Harvey IS, Allsopp M, Whitt-Glover MC. As a community, “we need to be more health conscious”: pastors’ perceptions on the health status of the Black Church and African-American communities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(3):570–9.

Harmon BE, Strayhorn S, Webb BL, et al. Leading God’s people: perceptions of influence among African–American pastors. J Relig Health. 2018;57:1509.

Ackermann RT, Marrero DG. Adapting the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention for delivery in the community: the YMCA model. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(1):74–65.

Ackermann RT, Liss DR, Finch EA, Schmidt KK, Hays LM, Marrero DG, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness trial for preventing type2 diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2328–34.

Ma J, Yank V, Xiao L, Lavori PW, Wilson SR, Rosas LG, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention for weight loss into primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):113–21.

Amundson HA, Butcher MK, Gohdes D, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program into practice in the general community: findings from the Montana Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(2):209–10.

Sepah SC, Jiang L, Ellis RJ, McDermott K, Peters AL. Engagement and outcomes in a digital Diabetes Prevention Program: 3-year update. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000422.

Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):357–63.

Ritchie ND, Havranek EP, Moore SL, Pereira RI. Proposed Medicare coverage for diabetes prevention: strengths, limitations, and recommendations for improvement. Am J Prev Med. 53(2):260–263.

Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff. 2012;31(1):67–75.

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, AuYoung M, Moin T, Datta SK, Sparks JB, et al. Implementation findings from a hybrid III implementation-effectiveness trial of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Implem Sci. 2017;12(1):94.

Marrero DG, Palmer KNB, Phillips EO, Miller-Kovach K, Foster GD, Saha CK. Comparison of commercial and self-initiated weight loss programs in people with prediabetes: a randomized control trial. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):949–56.

Eaglehouse YL, Venditti EM, Kramer MK, Arena VC, Vanderwood KK, Rockette-Wagner B, et al. Factors related to lifestyle goal achievement in a diabetes prevention program dissemination study. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(4):873–80.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the tremendous contributions of our faith and health organization partners, including the KC FAITH Initiative Community Action Board, along with the committed implementation of Project FIT by church leaders with their church members and community members served through their outreach ministries.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities [R24 MD007951].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

No authors of this manuscript have any conflict of interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards University of Missouri – Kansas City Institutional Review Board (Protocol ID: 14-231) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 13.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berkley-Patton, J., Bowe Thompson, C., Bauer, A.G. et al. A Multilevel Diabetes and CVD Risk Reduction Intervention in African American Churches: Project Faith Influencing Transformation (FIT) Feasibility and Outcomes. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 7, 1160–1171 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00740-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00740-8