Key summary points

The aim of this study was to determine whether DOAC-users with a hip fracture have delayed surgery, longer length of hospital stay or altered risk of bleeding complications compared to non-users.

AbstractSection FindingsDOAC-users with a hip fracture did not have increased surgical delay, length of stay or risk of reported bleeding complications compared to patients without anticoagulation prior to surgery.

AbstractSection MessageOur study does not support delayed surgery for DOAC-users suffering a hip fracture.

Abstract

Purpose

The perioperative consequences of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in hip fracture patients are not sufficiently investigated. The primary aim of this study was to determine whether DOAC-users have delayed surgery compared to non-users. Secondarily, we studied whether length of hospital stay, mortality, reoperations and bleeding complications were influenced by the use of DOAC.

Methods

The medical records of 314 patients operated for a hip fracture between 2016 and 2017 in a single trauma center were assessed. Patients aged < 60 and patients using other forms of anticoagulation than DOACs were excluded. Patients were followed from admission to 6 months postoperatively. Surgical delay was defined as time from admission to surgery. Secondary outcomes included length of hospital stay, transfusion rates, perioperative bleeding loss, postoperative wound ooze, mortality and risk of reoperation. The use of general versus neuraxial anaesthesia was registered. Continuous outcomes were analysed using Students t test, while categorical outcomes were expressed by Odds ratios.

Results

47 hip fracture patients (15%) were using DOACs. No difference in surgical delay (29 vs 26 h, p = 0.26) or length of hospital stay (6.6 vs 6.1 days, p = 0.34) were found between DOAC-users and non-users. DOAC-users operated with neuraxial anaesthesia had longer surgical delay compared to DOAC-users operated with general anaesthesia (35 h vs 22 h, p < 0.001). Perioperative blood loss, transfusion rate, risk of bleeding complications and mortality were similar between groups.

Conclusion

Hip fracture patients using DOAC did not have increased surgical delay, length of stay or risk of reported bleeding complications than patients without anticoagulation prior to surgery. The increased surgical delay found for DOAC-users operated with neuraxial anaesthesia should be interpreted with caution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have emerged based on randomized clinical trials, active marketing and less demands concerning monitoring compared to warfarin. From 2014 to 2018, the prevalence of DOAC-users increased with 150% in Norway and the drugs as a group have surpassed warfarin [1]. Increasing use of DOACs has also been observed in Germany, Belgium and The Netherlands [2]. Suffering a hip fracture results in an evident excess mortality [3], and knowledge on how to reduce complications is, therefore, important. Reduced kidney function, co-medication, drug interaction and altered distribution may affect the clinical outcome in hip fracture patients using such anticoagulant compounds [4].

Systemic thromboembolic events are important causes of mortality [5, 6]. On the other hand, DOACs may accentuate bleeding triggered by trauma and surgery. Whether DOACs should be temporarily paused to avoid surgical and anaesthesiological complications and, if so, when it should be paused remains to be established. Anticoagulation has in several studies been identified as a risk factor for delayed hip fracture surgery [7,8,9,10]. Most guidelines advocate that hip fracture surgery should be performed within 48 h after admission, preferably within 24 h, to reduce the rate of medical complications and mortality [11,12,13]. Earlier studies have indicated that patients exposed for DOAC before the hip fracture wait longer for surgery than recommended in treatment guidelines [14,15,16]. The consequences of DOAC on semi-urgent surgery such as for hip fracture patients has not been thoroughly investigated.

Currently, there is need for guidelines on how to handle DOACs in the treatment of hip fracture patients. The primary aim of this study was to determine whether hip fracture patients using DOACs prior to the fracture have delayed surgery or longer length of hospital stay compared to non-DOAC-users. Secondarily, we wanted to investigate whether mortality and perioperative complications occur more frequently among hip fracture patients using DOAC.

Methods

Study design

This is a retrospective descriptive study of hip fracture patients operated at one Norwegian single trauma center December 2016–December 2017. We extracted 360 patients electronically from the hospital database using ICD-10 diagnosis codes S72.0–S72.2. Demographic data and surgical outcomes for the included patients were retrieved directly from patient records by one experienced researcher (SLS). Patient records at the hospital consisted of day-to-day documentation by the anaesthetists and orthopaedic surgeons and medical records logged by physicians and nurses. The Regional Ethics Committee (REK) classified the study as quality assurance, thus we did not need ethical assessment (case number 1366/REK). The hospital data protection officer approved the study.

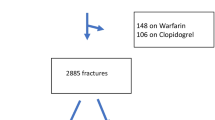

Patients

Patients with acute intracapsular or extracapsular hip fractures undergoing any type of surgery were included in the study. We aimed to compare hip fracture patients using DOAC at time of fracture with patients without anticoagulation at time of fracture. Patients under the age of 60 (n = 23) and patients using other forms of anticoagulation than DOACs (n = 23) were excluded, resulting in a study population of 314 patients.

Outcomes

We stratified the patients according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classes 1–2 and 3–5 to compare comorbidity between the studied groups. When comparing the rate of cognitive impairment reported between the study groups, patients with unknown preoperative cognitive status were excluded (n = 20). Time from admission to surgery (surgical delay) was reported in hours and length of stay (LOS) in days. In-hospital mortality and both mortality and readmissions within 30 days and within 6 months of operation were registered. Blood transfusion rates and transfusion amounts (allogenic red blood cells infused in standardized units) were collected from the medical records signed by the responsible physicians. In-hospital guidelines recommended blood transfusion therapy to be administered for patients with a haemoglobin below 9 g/dL monitored at the wards. The concentration of haemoglobin was listed at admission and the morning after surgery and the difference was calculated (change in haemoglobin concentration). Intraoperative blood loss estimated by the surgical team was registered from the anaesthesia journal in milliliters (mL). Postoperative bleeding and wound complications were recorded if the intraoperative or postoperative journals by the physicians reported so. Wound ooze was defined as clinically identified ooze with or without bleeding described by the doctors postoperatively. The type of anaesthesia was registered as general anaesthesia (total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) or inhalational anaesthesia) or neuraxial anaesthesia (spinal anaesthesia). We compared surgical delay and LOS within the groups receiving neuraxial versus general anaesthesia.

Statistical analysis

Our main outcome, surgical delay, was used to calculate the number of patients needed to achieve statistical significance between the groups. Based on guidelines from the Norwegian Knowledge Center hip fracture patients should preferable be operated within 24 h and no later than 48 h after admission [12]. Standard deviation was calculated from hip fracture patients with a surgical delay of less than 96 h reported to the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register and found to be 15.1 h. Based on alpha of 0.05 and beta of 0.9, 28 patients were needed in each group. Since 9.4% of Norwegian patients > 60 years were using DOAC in 2017 (Norwegian Institute of Public Health 2019), the total sample size was calculated to be 300. To account for exclusion criteria’s and missing information, we increased the sample size with 20%.

We performed univariate exploration of study variables; for continuous data, the assumption of homogeneity of variance between groups was assessed using the Levene’s test. Where the assumption holds a Students t test was used, otherwise the Welch’s t test was applied. Odds ratios (ORs) were used to express categorical outcomes and patients without DOAC were used as a reference group. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24.0; IBM Corp. Armonk, New York) for Windows was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Of the 314 included patients, 47 patients (15%) were DOAC-users before the hip fracture and 267 patients (85%) were not using anticoagulation before the fracture (Table 1). Hip fracture patients using DOAC were more likely to have a high ASA class (ASA 3–5) compared to non-users.

Time to surgery and hospital stay

DOAC-users and non-anticoagulated patients had similar time interval from admission to surgery (29 vs 26 h, p = 0.26, respectively) and similar length of hospital stay (LOS) (6.6 vs 6.1 days, p = 0.34, respectively) (Table 2).

Complications

The mean blood loss during surgery for all patients (n = 314) was 219 mL. Mean blood loss, fall in haemoglobin and transfusion rates were comparable in both groups (Table 2).

Bleeding complications were reported in three patients (0.9% of all patients); two patients had an excessive bleeding during surgery, while a third patient developed a postoperative haematoma restricted to the operation site. No bleeding complications were reported among the DOAC-users.

Wound oozing with or without bleeding were described in 27 patients (8.6%) and more frequently among DOAC-users than patients without anticoagulation (26% vs 5.6%, respectively) (Table 2). Among all patients (n = 314), postoperative wound leakage was associated with a longer hospital stay than for patients without wound exudation (LOS 9 vs 6 days, respectively, p < 0.001).

The 30-day mortality for all patients (n = 314) was 12%. DOAC-users had corresponding mortality in the hospital, within 30 days and within 6 month compared to non-users (Table 2). Furthermore, 30-day and 6-month risk of readmission were similar between DOAC-users and non-users [30 days: 26% vs 17%, respectively, OR 1.65 (0.80–3.41)] [6 months: 36% vs 26%, OR 1.63 (0.85–3.13)].

Antiaggregants

Among the DOAC-users, two hip fracture patients were also using clopidogrel (4.3%) while the remaining 45 patients where not using antiaggregant therapy (95.7%).

In the non-anticoagulated group, 92 patients (34.5%) were using 1 antiplatelet drug while ten patients (3.7%) were using two antiplatelet drugs. Time to surgery, perioperative blood loss, transfusion rate, risk of bleeding complications and mortality were similar between non-anticoagulated patients and DOAC-patients both when including and excluding patients with clopidogrel in addition to DOAC.

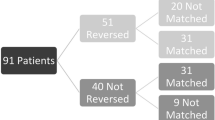

Anaesthesia

General anaesthesia was administered to 32 (10%) of all patients. When comparing general to neuraxial anaesthesia, no differences in time from admission to surgery (surgical delay) or LOS was found. A significantly higher percentage of DOAC-users received general anaesthesia than non-users [22 patients (47%) vs 10 (3.8%), p < 0.001]. The DOAC-users that received neuraxial anaesthesia (n = 25) had significantly longer surgical delay compared to those who received general anaesthesia (35 h vs 22 h, p < 0.001). DOAC-users treated with neuraxial anaesthesia trended toward a longer LOS, yet the results were not significant (7.1 vs 6.1 days, p = 0.1).

Discussion

In this single-centre retrospective descriptive study investigating hip fracture patients, the use of DOACs at the time of fracture was not found to influence surgical delay or length of stay compared to non-users. Furthermore, no differences in perioperative blood loss, transfusion rates or risk of bleeding complications between DOAC-users and non-users were disclosed. Hip fracture surgery was more frequently performed in general anaesthesia in DOAC-users, and the use of neuraxial anaesthesia for DOAC-users was associated with a longer surgical delay. This should be seen in relation to primary findings of no difference in surgical delay and length of stay between the compared groups. The high rate of cognitive impairment reported in this study was in line with a previous Norwegian study where 38% of home-dwelling hip fracture patients had cognitive impairment [17].

Studies investigating hip fracture treatment and the use of anticoagulants have so far reported conflicting results. While increased risk of complications was detected in one study [18], other studies discovered no such effect [19, 20]. These diverse findings could be explained by different perioperative administration of anticoagulant drugs. Due to a lack of international established guidelines, patients tend to be treated according to local routines in each hospital.

DOACs are approved for prevention of thromboembolism from non-valvular atrial fibrillation and to treat or prevent recurring deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism [21,22,23]. These indications may explain why a higher burden of comorbidity was found among hip fracture patients using a DOAC compared to non-users in our study. Despite this increased comorbidity, we were not able to find increased risk of perioperative blood loss, transfusion rates, bleeding complications or mortality for the DOAC-users compared to the less comorbid non-users. Our findings are in contrast to another study reporting a higher one-year mortality among hip fracture patients using DOAC compared to non-users [24]. However, the excess mortality may be explained by higher age, more comorbidity and longer surgical delay than in our patients.

Earlier hip fracture surgery has been associated with reduced LOS and reduced frequency of immobilization-related complications [25,26,27,28], and large resources have been applied to promote earlier surgical interventions [29]. Several studies have found increased surgical delay for DOAC-users [16, 18, 24], and the authors question whether the use of DOAC before the hip fracture results in unnecessary long surgical delay [14, 24, 30,31,32]. In contrast, our DOAC-using patients did not wait significantly longer for surgery than the non-users. Another study investigated hip fracture patients using DOACs compared to matched controls with a median of only 19 h from admission to surgery [30]; no association between surgical delay and perioperative fall in haemoglobin, transfusion rate or reoperation for DOAC-users was found. As our study did not find increased bleeding—and transfusion—complications among patients using DOAC, early surgical interventions appear safe.

The prevalence and risk factors for surgical site infections is sparsely studied in the geriatric hip fracture population even though high age has been identified as a potential risk factor for such infections [33]. Our study revealed wound oozing five times more frequently among DOAC-users than patients without anticoagulation. Still, none of these patients underwent a reoperation due to wound ooze. We need to acknowledge that reoperation due to wound ooze is a late solution to persisting oozing. One earlier study has investigated DOAC-users’ risk of reoperation due to wound ooze and found no relation to surgical delay [30]. On the other hand, when studying hip fracture patients not accounting for chronic anticoagulation, surgical delay has been found to be a risk factor for wound infections [28, 33]. The association between wound ooze and longer LOS found in our study might have implications for health costs and patient treatment following a hip fracture.

In Norway, 80–90% of hip fracture patients are given neuraxial anaesthesia [34], correlating well to the prevalence found in our hospital (90%). There is no international consensus on neuraxial versus general anaesthesia for hip fracture patients [35]. General anaesthesia has earlier been associated with a longer LOS compared to neuraxial anaesthesia [36], yet a meta-study of 400,000 hip fracture patients revealed a clinically insignificant difference of only 0.3 days [37]. The increasing use of DOACs challenge current clinical practice because the potential ramifications of neuraxial anaesthesia in the anticoagulated patient [38]. European guidelines recommend that DOACs should be discontinued before surgery in line with their pharmacokinetic properties [39,40,41,42]. Potential neuraxial bleeding can be avoided by giving the hip fracture patients general anaesthesia, possibly explaining why general anaesthesia was used ten times more frequently in patients using DOAC at the time of fracture compared to non-users in our study. One explanation to this finding could be that some DOAC-users were scheduled for delayed surgery to be operated with neuraxial anaesthesia. Another likely explanation is that for these DOAC-users, the chosen modality ended up being neuraxial anaesthesia, because their surgery already had been delayed for other reasons, in example access to theatre and preoperative medical stabilization.

Strengths and limitations

We studied patients treated at a large trauma hospital using patient records processed by one researcher, thereby increasing the quality and reproducibility of our work. We cannot generalize our findings to other hospitals or countries with other treatment algorithms. However, we believe that our university hospital is representable also for hip fracture treatment in other Norwegian hospitals. Similar surgical delay between DOAC-users and non-users further support comparable preoperative management of all the studied patients.

The sample size was calculated based on our main outcome surgical delay using data from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register [13]. However, we assessed several other outcomes as well in our study, thereby potentially working with insufficient sample sizes and lack of power. Unfortunately, the size of our study prevented stratified analyses of the different types of DOAC. The retrospective study design allowed us to report associations between DOAC and perioperative outcomes, yet causality cannot be proven. For example, we cannot exclude the risk of confounding by comorbidity when it comes to the choice of anaesthesia and surgical delay. Due to the abovementioned weaknesses of our study, we request future prospective clinical trials targeting hip fracture patients exposed for DOACs and the consequences of fast track surgery versus surgery timed after drug excretion. Further, we acknowledge a need for further studies structurally targeting wound assessment and wound ooze for DOAC-users suffering a hip fracture.

Conclusion

In our cohort of 314 hip fracture patients DOAC-users did not have increased surgical delay, LOS or risk of reported bleeding complications compared to patients without anticoagulation prior to surgery. Our study does not support delayed surgery for DOAC-users. The increased surgical delay found for DOAC-users operated with neuraxial anaesthesia compared to general anaesthesia should be interpreted with caution.

Change history

23 July 2020

The original version of this article unfortunately contained a mistake.

References

No authors listed (2019) Norwegian Institute of Public Health, The prescription registry. Indivual site for retrieving data accessed 05.12.19. https://reseptregisteret.no/Prevalens.aspx

de Jong LA, Knoops M, Gout-Zwart JJ, Beinema MJ, Hemels MEW, Postma MJ, Boruwers JRBJ (2018) Trends in direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) use: health benefits and patient preference. Neth J Med 76(10):426–430

Solbakken SM, Meyer HE, Stigum H, Søgaard AJ, Holvik K, Magnus JH, Omsland TK (2017) Excess mortality following hip fracture: impact of self-perceived health, smoking, and body mass index. A NOREPOS study. Osteoporos Int 28(3):881–887

Verma A, Ha ACT, Rutka JT, Verma S (2018) what surgeons should know about non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants: a review. JAMA Surg 153(6):577–585

Vera-Llonch M, Hagivara M, Oster G (2006) Clinical and economic consequences of bleeding following major orthopedic surgery. Thromb Res 117(5):569–577

Dahl OE, Caprini JA, Colwell CW Jr et al (2005) Fatal vascular outcomes following major orthopedic surgery. Thromb Haemost 93(5):860–866

Fantini MP, Fabbri G, Laus M et al (2011) Determinants of surgical delay for hip fracture. Surgeon 9(3):130–134

Eardley WG, Macleod KE, Freeman H, Tate A (2014) “Tiers of delay”: warfarin, hip fractures, and target-driven care. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 5(3):103–108

Tran T, Delluc A, de Wit C, Petrcich W, Le Gal G, Carrier M (2015) The impact of oral anticoagulation on time to surgery in patients hospitalized with hip fracture. Thromb Res 136(5):962–965

Ranhoff AH, Martinsen MI, Holvik K, Solheim LF (2011) Use of warfarin is associated with delay in surgery for hip fracture in older patients. Hosp Pract 39(1):37–40

No authors listed (2015) Norwegian Directorate of Health (Helsedirektoratet). Preoperative wait time for hip fracture patients, National Quality Indicator System: Quality indicator description. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/statistikk/statistikk/kvalitetsindikatorer/behandling-av-sykdom-og-overlevelse/hoftebrudd-operert-

Lindahl AK, Talsnes O, Figved W et al (2014) Measures for increased survival after hip fractures. Publication from The National Knowledge Center for the Health Service. https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/notater/2014/tiltak-for-okt-overlevelse-etter-hoftebrudd2 (date last accessed 16 July 2019)

Leer-Salvesen S, Engesaeter LB, Dybvik E, Furnes O, Kristensen TB, Gjertsen JE (2019) Does time from fracture to surgery affect mortality and intraoperative medical complications for hip fracture patients? An observational study of 73 557 patients reported to the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register. Bone Jt J 101-B(9):1129–1137

Hourston GJ, Barrett MP, Khan WS, Vindlacheruvu M, McDonnell SM (2019) New drug, new problem: do hip fracture patients taking NOACs experience delayed surgery, longer hospital stay, or poorer outcomes? Hip Int. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120700019841351

Linnerud I, Viktil K, Ranhoff A, Molden E (2016) Bruk av direktevirkende orale antikoagulantia og andre antitrombotika blant eldre hoftebruddspasienter; prevalens og kliniske aspekter. [The use of direct oral anticoagulants and other antithrombotic agents among elderly hip fracture patients; prevalence and clinical aspects] Master thesis in clinical farmacology at the University of Oslo in 2016. https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/51405/Ina-Linnerud-masteroppg-2016-DOAK-og-hoftebrudd.pdf?sequence=8. Accessed 05 Dec 2019

Franklin NA, Ali AH, Hurley RK, Mir HR, Beltran MJ (2018) Outcomes of early surgical intervention in geriatric proximal femur fractures among patients receiving direct oral anticoagulation. J Orthop Trauma 32(6):269–273

Ranhoff AH, Holvik K, Martinsen MI, Domaas K, Solheim LF (2010) Older hip fracture patients: three groups with different needs. BMC Geriatr 10:65

Frenkel Rutenberg T, Velkes S, Vitenberg M, Leader A, Halavy Y, Raanani P et al (2018) Morbidity and mortality after fragility hip fracture surgery in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists and direct oral anticoagulants. Thromb Res 166:106–112

Gleason LJ, Mendelson DA, Kates SL, Friedman SM (2014) Anticoagulation management in individuals with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 62(1):159–164

Cohn MR, Levack AE, Trivedi NN, Villa JC, Wellman DS, Lyden JP et al (2017) The hip fracture patient on warfarin: evaluating blood loss and time to surgery. J Orthop Trauma 31(8):407–413

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A et al (2009) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 361(12):1139–1151

Flaker G, Lopes RD, Hylek E, Wojdyla DM, Thomas L, Al-Khatib SM, Sullivan RM, Hohnloser SH, Garcia D, Hanna M, Amerena J, Harjola VP, Dorian P, Avezum A, Keltai M, Wallentin L, Granger CB, ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators (2014) Amiodarone, anticoagulation, and clinical events in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 64(15):1541–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.967

Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM, ROCKET AF Investigators (2011) Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365(10):883–891

Schermann H, Gurel R, Gold A, Maman E, Dolkart O, Steinberg EL et al (2019) Safety of urgent hip fracture surgery protocol under influence of direct oral anticoagulation medications. Injury 50(2):398–402

Grimes JP, Gregory PM, Noveck H, Butler MS, Carson JL (2002) The effects of time-to-surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture. Am J Med 112(9):702–709

Verbeek DO, Ponsen KJ, Goslings JC, Heetveld MJ (2008) Effect of surgical delay on outcome in hip fracture patients: a retrospective multivariate analysis of 192 patients. Int Orthop 32(1):13–18

Haleem S, Heinert G, Parker MJ (2008) Pressure sores and hip fractures. Injury 39(2):219–223

Cordero J, Maldonado A, Iborra S (2016) Surgical delay as a risk factor for wound infection after a hip fracture. Injury 47(Suppl 3):S56–S60

Larsson G, Holgers KM (2011) Fast-track care for patients with suspected hip fracture. Injury 42(11):1257–1261

Mullins B, Akehurst H, Slattery D, Chesser T (2018) Should surgery be delayed in patients taking direct oral anticoagulants who suffer a hip fracture? A retrospective, case-controlled observational study at a UK major trauma centre. BMJ Open 8(4):e020625

Lott A, Haglin J, Belayneh R, Konda SR, Leucht P, Egol KA (2019) Surgical delay is not warranted for patients with hip fractures receiving non-warfarin anticoagulants. Orthopedics 42(3):e331–e335

Hoerlyck C, Ong T, Gregersen M, Damsgaard EM, Borris L, Chia JK et al (2020) Do anticoagulants affect outcomes of hip fracture surgery? A cross-sectional analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 140(2):171–176

Liu X, Dong Z, Li J, Feng Y, Cao G, Song X et al (2019) Factors affecting the incidence of surgical site infection after geriatric hip fracture surgery: a retrospective multicenter study. J Orthop Surg Res 14(1):382

Furnes O, Engesæter, LB, Gjertsen JE, Fenstad AM, Bartz-Johannessen C, Dybvik E, Fjeldsgaard K, Gundersen T, Hallan G (2019) Annual report, Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 2019. https://nrlweb.ihelse.net/eng/Rapporter/Report2019_english.pdf

Johansen A, Golding D, Brent L, Close J, Gjertsen JE, Holt G, Hommel A, Pedersen AB, Rock ND, Thorngren KG (2017) Using national hip fracture registries and audit databases to develop an international perspective. Inj Int J Care Inj 48(10):2174–2179

Neuman MD, Rosenbaum PR, Ludwiq JM, Zubizarreta JR, Silber JH (2014) Anesthesia technique, mortality, and length of stay after hip fracture surgery. JAMA 25(311):2508–2517

Van Waesberghe J, Stevanovic A, Rossaint R, Coburn M (2017) General vs. neuraxial anaesthesia in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol 17:8

Jinlei L, Halaszynski T (2015) Neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks in patients taking anticoagulant or thromboprophylactic drugs: challenges and solutions. Local Reg Anesth 8:21–32

Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Rowlingson JC, Enneking FK, Kopp SL, Benzon HT et al (2010) Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (third edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med 35(1):64–101

Gogarten W, Vandermuelen E, Van Aken H et al (2010) Regional anaesthesia and antithrombotic agents: recommendations of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol 27:999

Wysokinski WE, McBane RD (2012) Periprocedural bridging management of anticoagulation. Circulation 126:486

Narouze S, Benxon HT, Provenzano DA, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer TR, Rauck R, Huntoon M (2015) Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications: guidelines from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 40(3):182–212

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by University of Bergen.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLS conducted the study of patient records. All authors participated in the study protocol, the application for ethical assessment and the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The Regional Ethics Committee (REK) classified the study as quality assurance, thus we did not need ethical assessment (case number 1366/REK). The hospital data protection officer approved the study.

Consent to participate

Our study involves hip fracture patients with a 1 year mortality of 25% and an even larger prevalence of cognitive impairment. We have performed a descriptive study using patient records without consent due to the patient demographics (age, mortality and cognitive impairment) by conducting a risk assessment taking into account the potential gain in quality of future patient treatment. The Regional Ethics Committee (REK) classified the study as quality assurance, thus we did not need ethical assessment (case number 1366/REK). The hospital data protection officer approved the study.

Consent for publication

The hospital data protection officer approved the study. We refer to the classification from the Regional Ethics Committee.

Availability of data and material

Our data have been deidentified and stored in a secure server area only available for Eva Dybvik and Sunniva Leer-Salvesen. The data will be deleted 5 years after the study.

Code availability

IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24.0; IBM Corp. Armonk, New York) for Windows was used for the statistical analyses.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The presentation of Table 2 was incorrect.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leer-Salvesen, S., Dybvik, E., Ranhoff, A.H. et al. Do direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) cause delayed surgery, longer length of hospital stay, and poorer outcome for hip fracture patients?. Eur Geriatr Med 11, 563–569 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00319-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00319-w