Abstract

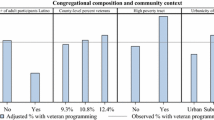

Using data from a nationally representative sample of U.S. congregations, this study estimates the proportion of congregations that provide programs or activities that serve people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and examines the effects of congregational characteristics on the likelihood of having them. The analysis finds that 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.034–0.078) of U.S. congregations (roughly 18,500 (95% CI, 11,300–25,800) congregations) provide programs or activities to PLWHA. Numerous congregational characteristics increase the likelihood that congregations provide them: the presence of openly HIV positive people in the congregation, having a group that assesses their community’s needs, religious tradition, and openness to gays and lesbians. By building on previous research, this study provides further information about the scope of religious congregations’ involvement with PLWHA and also insight into which congregations may be willing to collaborate with other organizations to provide care for PLWHA.

Resumen

Utilizando datos de una muestra nacional representativa de las congregaciones de los EEUU, este estudio estima el porcentaje de las congregaciones que ofrecen programas o actividades que atienden a personas que viven con VIH/SIDA (PVVS Personas Viviendo con VIH y SIDA) y examina los efectos de las caracteristicas de la congregación, en la probabilidad que les afectan. El análisis revela que el 5,6% (95% intervalo de confianza [IC], 0.034 a 0.078) de las congregaciones de EE.UU. (alrededor de 18.500 (IC 95% 11.300–25.800) congregaciones) ofrecen programas o actividades para las PVVS. Muchas características de la congregación aumentan la probabilidad que las congregaciones ofrecen: la presencia de personas abiertamente VIH positivas en la congregación, la presencia de un grupo que evalúa las necesidades de su comunidad, la tradición religiosa, y la aceptación a los gays y lesbianas. Al basarse en la investigación anterior, este estudio provee más información sobre el alcance de la participación de las congregaciones religiosas con las PVVS y también comprender cuales congregaciones pueden estar dispuestas a colaborar con otras organizaciones para brindar atención a las PVVS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Drawing a nationally representative probability sample of congregations is not otherwise possible because there is no complete list of U.S. congregations [5].

Chaves and Anderson [(30 p6)] provide an example to help explain this issue, “Suppose that the universe contains only two congregations, one with 1,000 regular attenders and the other with 100 regular attenders. Suppose further that the 1,000-person congregation supports a food pantry and the 100-person congregation does not. We can express this reality in one of two ways. We can say that 91 percent of the people are in a congregation that supports a food pantry (1,000/1,100), or we can say that 50 percent of the congregations support a food pantry (1/2). Both of these are meaningful numbers. Ignoring the over-representation of larger congregations, a percentage or mean from the NCS is analogous to the 91 percent in this example. Weighted inversely proportional to congregational size, a percentage or mean is analogous to the 50 percent in this example. The first number views congregations from the perspective of the average attender, which gives greater weight to congregations with more people in them; the second number views them from the perspective of the average congregation, ignoring size differences.”

As with other social surveys, the National Congregations Study had missing data which could bias the results. Thus, for the independent variables, we decided to use a random multiple imputation technique that allows us to retain cases otherwise lost and which proves to provide more efficient statistical estimates. Multiple imputation [36] involves imputing values for each missing value in a data set m times. In each of the m created data sets, the observed (non-missing) values are not transformed while the missing data are drawn randomly from the conditional joint distribution of the other variables in the data set. Each of the m data sets is analyzed separately. The results from these analyses are combined to account for within sample variation in the data and between sample variation created by multiple imputation. The random imputation process retains the original variability found in the data and thus reflects the fundamental uncertainty of our estimates, thus making it preferable to other techniques such as imputing the mean or using linear regression models. We set the number of imputed datasets at thirty to generate more efficient coefficient estimates [37].

References

Muñoz-Laboy MA, Murray L, Wittlin N, Garcia J, Terto V Jr, Parker RG. Beyond faith-based organizations: using comparative institutional ethnography to understand religious responses to HIV and AIDS in Brazil. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):972–8.

Schoepf BG. International AIDS research in anthropology: taking a critical perspective on the crisis. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2001;30:335–61.

Hicks KE, Allen JA, Wright EM. Building holistic HIV/AIDS responses in African-American urban faith communities-a qualitative, multiple case study analysis. Fam Community Health. 2005;28(2):184–205.

Berkley-Patton J, Bowe-Thompson C, Bradley-Ewing A, et al. Taking it to the pews: a CBPR-guided HIV awareness and screening project with black churches. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(3):218–37.

Chaves M. Congregations in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2004.

Chaves M, Tsitsos W. Congregations and social services: what they do, how they do it, and with whom. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 2001;30(4):660–83.

Derose KP, Mendel PJ, Kanouse DE, et al. Learning about urban congregations and HIV/AIDS: community-based foundations for developing congregational health interventions. J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):617–30.

Chambré SM. The changing nature of ‘faith’ in faith-based organizations: secularization and ecumenicism in four AIDS organizations in New York City. Soc Serv Rev. 2001;75(3):435–55.

Hernández EI, Burwell R, Smith J. Answering the call: how Latino churches can respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Notre Dame: Institute for Latino Studies. University of Notre Dame; 2007.

Koch JR, Beckley RE. Under the radar: AIDS ministry in the Bible Belt. Rev Relig Res. 2006;47(4):393–408.

McBride DC, McCoy CB, Chitwood DD, Inciardi JA, Hernandez EL, Mutch PM. Religious institutions as sources of AIDS information for street injection drug users. Rev Relig Res. 1994;35(4):324–34.

Tesoriero JM, Parisi DM, Sampson S, Foster J, Klein S, Ellemberg C. Faith communities and HIV/AIDS prevention in New York State: results of a statewide survey. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(6):544–56.

Derose KP, Mendel PJ, Palar K, et al. Religious congregations’ involvement in HIV: a case study approach. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1220–32.

Trinitapoli J, Ellison CG, Boardman JD. US religious congregations and the sponsorship of health-related programs. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2231–9.

Powell WW, DiMaggio PJ. The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991.

Herek GM, Capitanio JP. AIDS stigma and contact with persons with AIDS: effects of direct and vicarious contact. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1997;27(1):1–36.

Frenk SM, Chaves M. Proportion of U.S. congregations that have people living with HIV. J Relig Health. Forthcoming. Accessed 5 Nov 2011.

McRoberts OM. Streets of glory: church and community in a black urban neighborhood. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003.

Frenk SM. Beyond medicalization: congregations’ sponsorship of social services for people living with mental disorders. Dissertation. Department of Sociology: Duke University, Durham, NC; 2011.

Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Billingsley A, Caldwell C. The characteristics of northern Black churches with community health outreach programs. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(4):575–9.

Cnaan RA. The invisible caring hand: American congregations and the provision of welfare. New York: New York University Press; 2002.

Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black church in the African American experience. Durham: Duke University Press; 1990.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2007, vol. 19. CDC: Atlanta; 2009.

Department of Health and Human Services and National Coalition of Pastors’ Spouses. HIV/AIDS: a manual for faith communities. Washington, DC: USDHHS; 2007.

Kniss F, Campbell DT. The effect of religious orientation on international relief and development organizations. J Sci Study Relig. 1997;36(1):93–103.

Kundtz DJ, Schlager BS. Ministry among God’s queer folk: LGBT pastoral care. Cleveland: Pilgrim Press; 2007.

Carroll JW. God’s potters: pastoral leadership and the shaping of congregations. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company; 2006.

Davis JA, Smith TW, Marsden PV. General Social Surveys, 1972–2006: Cumulative codebook. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center; 2007.

McPherson JM. Hypernetwork sampling: duality and differentiation among voluntary organizations. Soc Network. 1982;3(4):225–49.

Chaves M, Anderson SL. National Congregations Study cumulative codebook for waves I and II (1998 and 2006-2007). Duke University, Sociology Department; 2009.

Frenk SM, Anderson SL, Chaves M, Martin N. Assessing the validity of key informant reports about congregants’ social composition. Sociol Relig. 2011;72(1):78–90.

McPherson JM, Rotolo T. Measuring the composition of voluntary groups: a multitrait-multimethod analysis. Soc Forces. 1995;73(3):1097–115.

Chaves M, Anderson SL. Continuity and change in American congregations: introducing the second wave of the National Congregations Study. Sociol Relig. 2008;69(4):415–40.

Steensland B, Park JZ, Regnerus MD, Robinson LD, Wilcox WB, Woodberry RD. The measure of American religion: toward improving the state of the art. Soc Forces. 2000;79(1):291–318.

StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2009.

King G, Honaker J, Joseph A, Scheve K. Analyzing incomplete political science data: an alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2001;95(1):49–69.

Bodner TE. What improves with increased missing data imputations? Struct Equ Modeling. 2008;15(4):651–75.

Winship C, Radbill L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociol Methods Res. 1994;23(2):230–57.

Hadaway CK, Marler PL. How many Americans attend worship each week? an alternative approach to measurement. J Sci Study Relig. 2005;44(3):307–22.

Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Wasowski KU, Campion J, Mathisen J, et al. Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. J Community Psychol. 2000;28(1):91–102.

Acknowledgments

Data for this paper are drawn from the second wave of the National Congregations Study. The project was funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation (#0452269) as well as grants from the Lilly Endowment, Inc. (2006-1675-000), the Kellogg Foundation (P0118042), and the Louisville Institute (2005105). These grants supported the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data. Data collection was handled by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, and the data were cleaned at Duke University, Durham, NC. The authors would like to thank Dr. Nick De Silvia for translating the abstract into Spanish and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frenk, S.M., Trinitapoli, J. U.S. Congregations’ Provision of Programs or Activities for People Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav 17, 1829–1838 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0145-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0145-x