Abstract

Background

Previous research among primary care attenders in Latin America has noted that females and those with less education may over-report psychiatric complaints on the SRQ-20, compared with responses to a standardized psychiatric interview administered by a clinician. In this paper, the association between demographic and socioeconomic variables and misclassification by the SRQ-20 were investigated and the size of misclassification estimated in a population-based survey.

Method

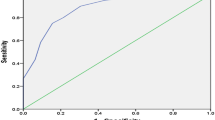

A cross-sectional survey of a random sample of private households included 683 adults aged 15 years and over living in Olinda, Recife Metropolitan Region, Pernambuco, Brazil. The SRQ-20 results were compared with an interview administered by a psychiatrist. The effect of demographic and socioeconomic variables on misclassification by the SRQ-20 was assessed by calculating the odds ratio (OR) for being a case on the SRQ-20 after adjustment for being a case on the psychiatric interview. Logistic regression was used to investigate the size of misclassification, adjusting the association between common mental disorders, defined by the SRQ-20,and different variables for the psychiatric interview results.

Results

In the univariate analysis, females, the elderly, the less educated, manual workers, housewives and migrants did tend to over-report complaints in the absence of symptoms. However, the apparent influence of age, education, occupation and migration on misclassification by the SRQ-20 was markedly reduced and became statistically non-significant after adjustment for sex and for the other variables in the table. In contrast, the gender effect was not altered after adjustment.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that misclassification on the SRQ-20 was mostly related to being female, though this did not entirely explain the increased prevalence of CMD in women in the sample. Further research is needed to understand why different ways of measuring CMD can lead to different results.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Araya RI, Wynn R, Lewis G (1992) Comparison of two self-administered psychiatric questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in primary care in Chile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 27:168–173

Furukawa TA, Goldberg DP, Rabe-Hesketh S, Űstűn TB (2001) Stratum-specific likelihood ratios of two versions of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 31:519–529

Goldberg DP (1972) The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Oxford University Press, London

Goldberg DP (1981) Estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorder from the results of a screening test. In: Wing JK, Bebbington P, Robins L (eds) What is a case? The problem of definition in psychiatric community surveys. Grant McIntyre, London, pp 129–136

Goldberg D, Huxley P (1992) Common Mental Disorders: A Biosocial model. Tavistock/Routledge, London New York

Goldberg DP, Oldehinkel T, Ormel J (1998) Why GHQ threshold varies from one place to another. Psychol Med 28:915–921

Harding T, De Arango M, Baltazar J, Climent CE, Ibrahim HH, Ladrido-Ignacio L, Srinivasa Murphy R, Wig NN (1980) Mental Disorders in primary health care: a study of the frequency and diagnosis in four developing countries. Psychol Med 10:231–242

Harpham T, Reichenheim M, Oser R, Thomas E, Hamid N, Jaswal S, Ludermir AB, Aidoo M (2003) How to Measure Mental Health in a Cost-Effective Manner. Health Policy and Planning 18(3):344–349

Hennekens CH,Buring JE (1987) Epidemiology in Medicine. Little, Brown and Company, Boston

Huber PJ (1967) The behaviour of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. Proceedings of the fifth Berkley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Vol 1. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 221–233

Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G (1992) Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med 22:465–486

Ludermir AB (2000) Inserção produtiva, gênero e saúde mental. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 16(2):109–118

Ludermir AB, Lewis G (2001) Links between social class and common mental disorders in Northeast Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 36(3):101–107

Ludermir AB, Lewis G (2003) Informal work and common mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38(9):485–489

Mari JJ, Williams P (1986) Misclassification by psychiatric screening questionnaires. J Chronic Dis 39(5):371–378

Mari JJ (1987) Psychiatric morbidity in three primary medical care clinics in the city of São Paulo: issues on the mental health of the urban poor. Soc Psychiatr 22:129–138

Fundação Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística—IBGE (1991) Censo demográfico de Pernambuco. IBGE, Rio de Janeiro

Fundação Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística—IBGE (1993) Indicadores IBGE. IBGE, Rio de Janeiro

Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS (1981) National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 38:381–389

Secretaria de Planejamento de Olinda (1988) Characterization of needy areas of Olinda city (draft) (in Portuguese). Secretaria de Saúde de Olinda, Olinda

Secretaria de Planejamento do Estado de Pernambuco (1996) Urban Poverty: basis for the formulation of an integrated action programme (draft) (in Portuguese). Fundação de Desenvolvimento da Região Metropolitana do Recife—FIDEM, Recife

Stansfeld S, Marmot MG (1992) Social class and minor psychiatric disorder in British civil servants: a validated screening survey using the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 22:739–749

Sturt E, Bebbington P, Hurry J, Tennant C (1981) The present state examination used by interviewers from a survey agency: report from MRC Camberwell Community survey. Psychol Med 11:185–192

Wing JK, Cooper PE, Sartorius N (1974) The measurements and classification of psychiatric symptoms. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

World Bank (1993) World Development Report 1993. University Press, Oxford

World Health Organization (1993) A user’s guide to the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (draft). WHO, Geneva

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ludermir, A.B., Lewis, G. Investigating the effect of demographic and socioeconomic variables on misclassification by the SRQ-20 compared with a psychiatric interview. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40, 36–41 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0840-2

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0840-2