Abstract

Purpose

To examine the intake and sources of added sugars (AS) of Australian children and adolescents, and compare their intake of free sugars (FS) to the recommended limit set by the World Health Organization (<10 % energy from FS).

Method

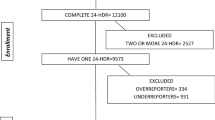

Data of 4140 children and adolescents aged 2–16 years with plausible intakes based on 2 × 24 h recalls from the 2007 Australian National Children Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey were used. AS content of foods was estimated based on a published method. Intakes of AS and FS, as well as food sources of AS, were calculated. One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between age groups and gender.

Results

The mean (SD) AS intake was 58.9 (35.1) g/day, representing 11.9 (5.6) % of daily energy intake and 46.9 (17.5) % of daily total sugars intake. More than 80 % of the subjects had % energy from FS > 10 %. Significant increasing trends for AS intake, % energy from AS, % energy from FS across age groups were observed. Sugar-sweetened beverages (19.6 %), cakes, biscuits, pastries and batter-based products (14.3 %), and sugar and sweet spreads (10.5 %) were the top three contributors of AS intake in the whole sample. Higher contribution of AS from sugar-sweetened beverages was observed in adolescents (p trend < 0.001).

Conclusions

A large proportion of Australian youths are consuming excessive amounts of energy from AS. Since the main sources of AS were energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, interventions which target the reduction in these foods would reduce energy and AS intake with minimal impact to core nutrient intake.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pereira MA (2014) Sugar-sweetened and artificially-sweetened beverages in relation to obesity risk. Adv Nutr 5(6):797–808. doi:10.3945/an.114.007062

Malik VS, Hu FB (2012) Sweeteners and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: the role of sugar-sweetened beverages. Curr Diab Rep 12(2):195–203. doi:10.1007/s11892-012-0259-6

Kell KP, Cardel MI, Bohan Brown MM, Fernandez JR (2014) Added sugars in the diet are positively associated with diastolic blood pressure and triglycerides in children. Am J Clin Nutr 100(1):46–52. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.076505

Wang J (2014) Consumption of added sugars and development of metabolic syndrome components among a sample of youth at risk of obesity. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 39(4):512. doi:10.1139/apnm-2013-0456

Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB (2014) Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med 174(4):516–524. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13563

World Health Organization (2015) Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. World Health Organization, Geneva

Louie JC, Moshtaghian H, Boylan S, Flood VM, Rangan AM, Barclay AW, Brand-Miller JC, Gill TP (2015) A systematic methodology to estimate added sugar content of foods. Eur J Clin Nutr 69(2):154–161. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2014.256

U.S. Department of Agriculture What are added sugars? http://www.choosemyplate.gov/weight-management-calories/calories/added-sugars.html. Accessed 1 June 2015

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (2015) The 2007 Australian national children’s nutrition and physical activity survey volume two: nutrient intakes. Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Lee AK, Binongo JN, Chowdhury R, Stein AD, Gazmararian JA, Vos MB, Welsh JA (2014) Consumption of <10% of total energy from added sugars is associated with increasing HDL in females during adolescence: a longitudinal analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 3(1):e000615. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000615

Livingstone MB, Rennie KL (2009) Added sugars and micronutrient dilution. Obes Rev 10(Suppl 1):34–40. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00563.x

Louie JCY, Tapsell LC (2015) Association between intakes of total vs added sugars on diet quality: a systematic literature review. Nutr Rev. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv044

Nicklas TA, O’Neil CE, Liu Y (2011) Intake of added sugars is not associated with weight measures in children 6–18 years: national health and nutrition examination surveys 2003–2006. Nutr Res 31(5):338–346. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2011.03.014

Vorster HH, Kruger A, Wentzel-Viljoen E, Kruger HS, Margetts BM (2014) Added sugar intake in South Africa: findings from the adult prospective urban and rural epidemiology cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 99(6):1479–1486. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.069005

Welsh JA, Cunningham SA (2011) The role of added sugars in pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am 58(6):1455–1466. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.09.009

Welsh JA, Sharma A, Cunningham SA, Vos MB (2011) Consumption of added sugars and indicators of cardiovascular disease risk among US adolescents. Circulation 123(3):249–257. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972166

Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB (2011) Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 94(3):726–734. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.018366

Zhang Z, Gillespie C, Welsh JA, Hu FB, Yang Q (2015) Usual intake of added sugars and lipid profiles among the U.S. adolescents: national health and nutrition examination survey, 2005–2010. J Adolesc Health 56(3):352–359. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.001

Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM (2010) Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 110(10):1477–1484. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010

McNulty H, Eaton-Evans J, Cran G, Woulahan G, Boreham C, Savage JM, Fletcher R, Strain JJ (1996) Nutrient intakes and impact of fortified breakfast cereals in school children. Arch Dis Child 75(6):474–481

Fayet F, Ridges LA, Wright JK, Petocz P (2013) Australian children who drink milk (plain or flavoured) have higher milk and micronutrient intakes but similar body mass index to those who do not drink milk. Nutr Res 33(2):95–102. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2012.12.005

US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture (2005) Dietary guidelines for Americans, 6th edn. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ (2004) Children and adolescents’ choices of foods and beverages high in added sugars are associated with intakes of key nutrients and food groups. J Adolesc Health 34(1):56–63

Bates B, Lennox A, Prentice A, Bates C, Page P, Nicholson S, Swan G (2014) National diet and nutrition survey: results from Years 1–4 (combined) of the rolling programme (2008/2009–2011/12)—executive summary. Public Health England, London

Ervin RB, Ogden CL (2013) Consumption of Added Sugars Among U.S. Adults, 2005–2010. Centre for Diseases Control and Prevention, Washington, USA

Svensson A, Larsson C, Eiben G, Lanfer A, Pala V, Hebestreit A, Huybrechts I, Fernandez-Alvira JM, Russo P, Koni AC, De Henauw S, Veidebaum T, Molnar D, Lissner L, IDEFICS consortium (2014) European children’s sugar intake on weekdays versus weekends: the IDEFICS study. Eur J Clin Nutr 68(7):822–828. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2014.87

Cobiac L, Record S, Leppard P, Syrette J, Flight I (2003) Sugars in the Australian diet: results from the 1995 National Nutrition Survey. Nutr Diet 60(3):152–173

Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (Australia), Preventative Health National Research Flagship, The University of South Australia (2008) 2007 Australian national children’s nutrition and physical activity surveys—main findings. Department of Health and Ageing (Australia), Canberra, Australia

University of South Australia, Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Research Organization, i-View Pty Ltd (2009) User Guide—2007 Australian national children’s nutrition and physical activity survey. Australian Department of Health and Ageing. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/AC3F256C715674D5CA2574D60000237D/$File/user-guide-v2.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul 2009

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2014) AMPM—USDA Automated multiple-pass method. USDA. http://www.ars.usda.gov/News/docs.htm?docid=7710. Accessed 21 May 2015

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (2008) AUSNUT2007 food composition database. FSANZ. http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/Pages/ausnut2007.aspx. Accessed 8 Nov 2013

Goldberg GR, Black AE, Jebb SA, Cole TJ, Murgatroyd PR, Coward WA, Prentice AM (1991) Critical evaluation of energy intake data using fundamental principles of energy physiology: 1. Derivation of cut-off limits to identify under-recording. Eur J Clin Nutr 45(12):569–581

University of South Australia, Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Research Organization, i-View Pty Ltd (2009) User guide—2007 Australian national children’s nutrition and physical activity survey

Harttig U, Haubrock J, Knuppel S, Boeing H (2011) The MSM program: web-based statistics package for estimating usual dietary intake using the Multiple Source Method. Eur J Clin Nutr 65(Suppl 1):S87–S91. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2011.92

Louie JC, Dunford EK, Walker KZ, Gill TP (2012) Nutritional quality of Australian breakfast cereals. Are they improving? Appetite 59(2):464–470. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2012.06.010

Cook T, Rutishauser IH, Allsopp R (2001) The Bridging Study—comparing results from the 1983, 1985 and 1995 Australian national nutrition surveys. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra

Ervin RB, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Ogden CL (2012) Consumption of added sugar among U.S. children and adolescents, 2005–2008. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2009) USDA Database for the Added Sugars Content of Selected Foods, Release 1. USDA. http://www.ars.usda.gov/services/docs.htm?docid=12107. Accessed 18 Feb 2013

Euromonitor International (2014) The Sugar Backlash and its Effects on Global Consumer Markets. Euromonitor International. http://www.euromonitor.com/the-sugar-backlash-and-its-effects-on-global-consumer-markets/report. Accessed 20 May 2015

Erickson J, Slavin J (2015) Total, added, and free sugars: are restrictive guidelines science-based or achievable? Nutrients 7(4):2866–2878. doi:10.3390/nu7042866

Albertson AM, Thompson D, Franko DL, Kleinman RE, Barton BA, Crockett SJ (2008) Consumption of breakfast cereal is associated with positive health outcomes: evidence from the national heart, lung, and blood institute growth and health study. Nutr Res 28(11):744–752. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2008.09.002

Barton BA, Eldridge AL, Thompson D, Affenito SG, Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Albertson AM, Crockett SJ (2005) The relationship of breakfast and cereal consumption to nutrient intake and body mass index: the national heart, lung, and blood institute growth and health study. J Am Diet Assoc 105(9):1383–1389. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.06.003

Girgis S, Neal B, Prescott J, Prendergast J, Dumbrell S, Turner C, Woodward M (2003) A one-quarter reduction in the salt content of bread can be made without detection. Eur J Clin Nutr 57(4):616–620. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601583

Somerset SM (2003) Refined sugar intake in Australian children. Public Health Nutr 6(8):809–813

Forshee RA, Storey ML (2001) The role of added sugars in the diet quality of children and adolescents. J Am Coll Nutr 20(1):32–43

Buzzard M (1998) 24-hour dietary recall and food record methods. In: Willett WC (ed) Nutritional Epidemiology, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 50–73

Tooze JA, Kipnis V, Buckman DW, Carroll RJ, Freedman LS, Guenther PM, Krebs-Smith SM, Subar AF, Dodd KW (2010) A mixed-effects model approach for estimating the distribution of usual intake of nutrients: the NCI method. Stat Med 29(27):2857–2868. doi:10.1002/sim.4063

Dekkers AL, Verkaik-Kloosterman J, van Rossum CT, Ocke MC (2014) SPADE, a new statistical program to estimate habitual dietary intake from multiple food sources and dietary supplements. J Nutr 144(12):2083–2091. doi:10.3945/jn.114.191288

Rangan AM, Kwan J, Flood VM, Louie JCY, Gill TP (2011) Changes in ‘extra’ food intake among Australian children between 1995 and 2007. Obes Res Clin Pract 5(1):e55–e63. doi:10.1016/j.orcp.2010.12.001

National Cancer Institute (2015) Dietary assessment primer. summary tables: recommendations on potential approaches to dietary assessment for different research objectives requiring group-level estimates. http://dietassessmentprimer.cancer.gov/approach/table.html. Accessed 21 May 2015

Acknowledgments

The original data of the 2007 ANCNPAS were collected by the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization and the University of South Australia. The authors would like to thank the Australian Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing for providing the survey data via the Australian Social Science Data Archive. The authors declare that those who carried out the original analysis and collection of the data bear no responsibility for the further analysis or interpretation included in this manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception of the study. HM and JL performed the statistical analyses. JL drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and interpreted the data, were involved in the subsequent edits of the manuscript, and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. All authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Louie, J.C.Y., Moshtaghian, H., Rangan, A.M. et al. Intake and sources of added sugars among Australian children and adolescents. Eur J Nutr 55, 2347–2355 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-015-1041-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-015-1041-8