Abstract

Acute/early HIV infection plays a critical role in onward HIV transmission. Detection of HIV infections during this period provides an important early opportunity to offer interventions which may prevent further transmission. In six US cities, persons with acute/early HIV infection were identified using either HIV RNA testing of pooled sera from persons screened HIV antibody negative or through clinical referral of persons with acute or early infections. Fifty-one cases were identified and 34 (68%) were enrolled into the study; 28 (82%) were acute infections and 6 (18%) were early infections. Of those enrolled, 13 (38%) were identified through HIV pooled testing of 7,633 HIV antibody negative sera and 21 (62%) through referral. Both strategies identified cases that would have been missed under current HIV testing and counseling protocols. Efforts to identify newly infected persons should target specific populations and geographic areas based on knowledge of the local epidemiology of incident infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is compelling evidence that acute/early HIV infection plays a critical role in onward HIV transmission. Acute HIV infection (AHI)—the period of weeks to about 2 months between HIV acquisition and completion of seroconversion (Zetola and Pilcher 2007)—is characterized by extremely high levels of virus in the blood and semen (Pilcher et al. 2004a, b; Stekler et al. 2008), leading to heightened infectiousness. Furthermore, although acute HIV shedding is over about 10 weeks post-infection (Zetola and Pilcher 2007), elevated onward transmission likely extends through the period of early infection, defined as the 6 month period after seroconversion (Cates et al. 1997; Kassuto and Rosenberg 2004; Stekler et al. 2008), due to ongoing high-risk behaviors (particularly if the newly infected person is unaware of his or her recent infection) (Cates et al. 1997; Koopman et al. 1997; Pao et al. 2005). Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) associated with these high-risk behaviors further increase transmission risk (Gray et al. 2001; Pilcher et al. 2004a, b; Pao et al. 2005). Finally, a transmission amplification effect may be expected because newly infected persons are likely to transmit the virus to individuals engaging in similar high-risk behaviors (Cates et al. 1997; Koopman, et al. 1997; Pilcher et al. 2005). Indeed, mathematical modeling (Koopman et al. 1997), phylogenetic studies (Pao et al. 2005; Brenner et al. 2007; Lewis et al. 2008) and epidemiologic studies (Wawer et al. 2005) indicate that high rates of forward transmission last for at least 6 months post-infection and that transmissions during this period may account for as many as half of new infections.

For these reasons, diagnosis of acute/early HIV infection followed by appropriate interventions to prevent further transmission holds promise as an effective biomedical HIV prevention strategy. However, the diagnosis of AHI, in particular, is problematic because despite the high sensitivity and specificity of currently used HIV antibody assays, AHI represents a “window period” ranging from weeks to about 2 month during which persons infected with HIV will test HIV antibody negative or indeterminate (Zetola and Pilcher 2007). To make the diagnosis of AHI, the presence of the virus itself must be detected in the blood using a plasma HIV RNA test. This can be accomplished through two strategies.

One strategy is a “public health approach” that incorporates routine screening of all HIV antibody negative or indeterminate specimens into pools which are then tested for HIV RNA (Flanigan and Tashima 2001; Quinn et al. 2000; Pilcher et al. 2005). Depending on the locality and population tested this approach has been shown to increase the detection of HIV infection approximately 4–10% compared to antibody testing alone (Pilcher et al. 2005; Priddy et al. 2007; Truong et al. 2006; Patel et al. 2006; Stekler et al. 2005).

A second strategy is a “medical approach” in which AHI is suspected based on clinical signs and symptoms combined with a history of possible recent exposure, which prompts specific diagnostic testing for AHI. An estimated 40–90% of persons with acute or recent HIV infection will report symptoms consistent with the acute retroviral syndrome. These symptoms include “flu-like” illness characterized by fever, headache, muscle aches, joint pain, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, diarrhea, and/or rash, and are similar to those found in other, more common viral and bacterial infections, including infectious mononucleosis, streptococcal pharyngitis, and cytomegalovirus infection (Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents 2008; Kassutto and Rosenberg 2004; Zetola and Pilcher 2007; Schacker et al. 1996). Unfortunately, the mild and non-specific nature of the signs and symptoms associated with the acute retroviral syndrome is a significant barrier to the diagnosis of AHI unless a clinician entertains the diagnosis and orders appropriate virus-specific diagnostic tests (Weintrob et al. 2003; Sudarshi et al. 2008).

This is the first in a series of five papers in this issue of the journal (see Remien et al. 2009; Steward et al. 2009; Atkinson et al. 2009; Kelly et al. 2009) that describe results from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study, an exploratory study with the aims of determining the feasibility of detecting and recruiting individuals with AHI into research studies; better understanding the social and psychological context of recent HIV transmissions; and assessing sexual behavior, substance use, and the psychological state of individuals during the periods before and after diagnosis. This research provides formative results to inform development of effective prevention interventions for persons with acute/early HIV infection. In the present study, we describe the two principal strategies used to identify and recruit study participants and present their clinical, demographic, risk behavior, HIV testing, and other selected characteristics.

Methods

The NIMH Multisite AHI Study was conducted at Brown University (Providence, RI,); Colombia University (New York City, NY,); University of California at Los Angeles (Los Angeles, CA,); University of California at San Diego (San Diego, CA,); University of California at San Francisco (San Francisco, CA,); Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI); and Yale University (New Haven, CT).

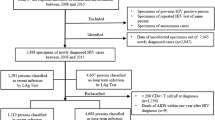

We used both the public health and medical approaches to identify AHI cases. The public health approach used routine HIV RNA testing of pooled serum or plasma samples that had yielded negative or indeterminate results on standard HIV antibody tests. This approach was utilized at sites attended by high risk individuals such as STD clinics, HIV testing venues that served men who have sex with men (MSM), and drug rehabilitation facilities. If a pool was found to be positive, it was divided into smaller pools and tested for HIV RNA until the individual(s) with acute infection were identified. Pool sizes varied between sites depending on the specimen volume and the time requirements to report out final results. Initial HIV antibody tests varied among the participating sites that tested pooled samples: Vironostika HIV-1 Microelisa System (viral lysate) (Biomerieux, Durham, NC) was used in Los Angeles, New Haven, and San Francisco; HIV rapid testing was performed using the Orasure whole blood test (Abbott, North Chicago, Ill), the Clearview whole blood test (Inverness, Waltham, Mass), or the OraQuick ADVANCE ® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (OraSure Technologies) in Providence; and the latter test was also used in New Haven.

Specimens were tested for HIV RNA using RT-PCR (Roche Ultrasensitive, Roche Diagnostics, Branchberg, NJ), or GenProbe HIV-1 Aptima test (GenProbe, San Diego) in Los Angeles; Versant HIV-1 RNA 3.0 bDNA Assay (Bayer HealthCare) was used in New Haven, Providence, and San Francisco.

The medical approach to identify individuals with AHI involved referrals from clinical colleagues, including experienced HIV providers, primary care providers for high-risk persons, HIV test sites and several established AHI clinical research programs. The diagnosis of AHI was made after a provider clinically suspected AHI and an initial negative or indeterminate HIV antibody test was followed by a positive HIV RNA test. While our original intent was to restrict study participation to persons diagnosed with AHI, due to the difficulty we encountered in identifying such cases we decided to make a protocol exception for six participants enrolled at the San Diego site who were diagnosed in the stage of early HIV infection based on positive initial HIV antibody/Western blot tests combined with a prior recent (<6 months) negative HIV antibody test.

The public health approach was utilized in Los Angeles; the medical approach was utilized in New York and San Diego; and both approaches were utilized in Providence, New Haven, and San Francisco.

Study participants were 18 years of age or older, were sufficiently proficient in English to complete study measures, and were determined to be acutely infected (or enrolled as a protocol exception as an early infection) as described above. Participants met with a study recruiter who explained the purpose of the research and obtained written informed consent and tracking information. Participants were asked to attend two interview sessions: the first targeted to be held within 4 weeks of the participant being informed of his or her diagnosis and the second targeted to be held 8 weeks later. At each session, participants completed both a structured survey and an in-depth interview. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Subject’s Institutional Review Board in each of the participating sites.

Results

Over an approximately 15 months period, 51 persons with acute or early HIV infection were identified and 34 (67%) were enrolled into the study [28 (82%) with AHI and 6 (18%) with early infections]: 6 (18%) were enrolled in Providence; 6 (18%) in New York City; 9 (26%) in Los Angeles; 6 (18%) in San Diego; 5 (15%) in San Francisco; and 2 (6%) in New Haven. In spite of intensive efforts, one site was unable to enroll participants. Thirteen (38%) participants were identified through HIV RNA pooled testing of 7,633 HIV antibody negative specimens and 21 (62%) were enrolled through clinical referral.

The demographic and other characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1; 32 (94%) were males, 15 (44%) were White, 13 (38%) were Hispanic, and 30 (88%) were MSM. During the 2 months before diagnosis, 13 (38%) reported sex with an HIV-infected partner, 10 (29%) reported meeting partner(s) on the Internet, 28 (82%) reported anal intercourse, 22 (65%) reported using one or more drugs, and 27 (79%) had multiple sex partners. Thirty (88%) participants reported regular testing for HIV of whom 25 tested every 6 months or less. During the 2 months before diagnosis, 14 participants (41%) reported visits to a health care professional. Eight of these 14 (57%) were seen in emergency departments, 5 of whom were seen 2 or 3 times.

The clinical characteristics and HIV test results of the study participants are shown in Table 2. Twenty-one (62%) patients presented with symptoms, consistent with the acute retroviral syndrome, including fever, headache, rash, muscle aches, sore throat, and swollen lymph glands. Five participants (15%) reported symptoms more likely to be due to an STD (e.g. pain on urination, penile chancre), and eight (24%) participants were asymptomatic. Twelve (35%) participants were known to be co-infected with another sexually transmitted infection (6 were co-infected with gonorrhea (GC) only, 3 with syphilis only, 2 with GC and syphilis, and 1 with GC and Chlamydia (CT)).

Initial HIV viral loads were available for 32 participants: 14 (44%) had viral loads >500,000 copies/mL; 6 (19%) were between 100,000 and 500,000 copies/mL; and 12 (38%) were <100,000 copies/mL.

Discussion

This study illustrates that both the public health and medical referral strategies can be successfully utilized to detect HIV infections that otherwise would not be diagnosed by standard antibody testing alone. Fifty-one individuals with acute or early HIV infection were identified and 34 were enrolled at six US study sites over an approximate 15 month study period. Of those enrolled, 13 (38%) were identified through pooled HIV RNA testing of 7,633 HIV antibody negative specimens and 21 (62%) were identified clinically, followed by HIV RNA or repeat HIV testing. Relying only on HIV antibody and Western blot assays performed once would have delayed or missed the diagnosis for the 28 individuals who were acutely infected.

Early detection of HIV infection allows appropriate clinical management (Weintrob et al. 2003) including treatment of STDs and the offer of partner counseling and referral services, which can interrupt transmission to others within an individual’s social and sexual network (Pilcher et al. 2005; Hightow et al. 2005; Yerly et al. 2001). An HIV diagnosis in itself, particularly in conjunction with counseling interventions, is associated with a significant reduction in risk behavior (Colfax et al. 2002; Weinhardt et al. 1999; Marks et al. 2005; Kalichman et al. 2001). We observed this phenomenon in our sample (Steward et al. 2009).

Because most cases of HIV are currently diagnosed in the chronic phase of infection (Pilcher et al. 2005), there is great potential for making strides in prevention through expansion of both the public health and medical approaches to AHI diagnosis. The public health approach should target populations in which local epidemiologic trends suggest that incident infections are occurring. Over one-third of participants in our study were found to be co-infected with an STD (this was a minimum estimate because our protocol did not require STD testing), suggesting that persons attending STD clinics are one such population (Pilcher et al. 2005; Stekler et al. 2005; Truong et al. 2006; Patel et al. 2006).

The majority of newly infected individuals, including about three-fourths of the participants in our study, have symptoms related to acute retroviral syndrome (Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents 2008; Zetola and Pilcher 2007; Kassutto and Rosenberg 2004; Schacker et al. 1996). Although symptoms prompt many individuals to present for medical evaluation after an infection event, AHI is rarely diagnosed (Schacker et al. 1996; Weintrob et al. 2003; Sudarshi et al. 2008). For the medical approach to AHI diagnosis to be successful, clinicians must become more adept at recognizing symptoms consistent with acute retroviral syndrome, evaluating individuals’ risks for HIV acquisition, employing HIV RNA testing when indicated, and appropriately interpreting results to optimize the timely diagnosis of AHI.

Clinicians should consider AHI in the differential diagnosis of all individuals presenting with nonspecific symptoms consistent with the acute retroviral syndrome and a possible recent HIV exposure, take a thorough sexual practice and drug use history, and order viral specific testing or immediate repeat testing if the initial HIV antibody test is negative. High risk individuals with an STD who have a negative HIV antibody test should be considered for reflex HIV RNA testing to rule out AHI. Finally, provider education in the clinical and counseling and testing setting should be continually reinforced to minimize missed AHI detection opportunities. The second paper of this series documents the need for education and training programs about AHI for populations-at-risk and for persons diagnosed with acute/early infection, as well as for providers (Remien et al. 2009).

This study had several limitations. First, both the public health and medical strategies to detect AHI were not uniformly applied in all sites and the number of cases identified by each method was small; therefore a direct comparison of the two approaches is not possible. Second, the cases we identified were primarily among MSM and likely only represented the local at-risk populations that had access to medical care or that sought HIV counseling and testing services in the six cities participating in this study.

Conclusions

These findings support the conclusion that both the public health and medical strategies are able to identify cases of AHI. However, pooled testing methods and specific diagnostic testing by clinicians will only succeed if these strategies reach populations where incident infections are occurring. Therefore, targeting specific populations within a geographic area based on the local epidemiology of incident infections with these strategies and efforts to educate medical providers and staff in HIV testing and counseling programs and at-risk communities about symptoms and situations where AHI should be suspected are likely to increase the diagnosis of AHI, opening the way for appropriate referrals for medical care, partner services and other behavioral interventions that may prevent further transmission.

References

Atkinson, J. H., Higgins, J., Vigil, O., Dubrow, R., Remien, R. H., Steward, W. T., Casey, C. Y., Sikkema, K. J., Correale, J., Ake, C., McCutchan, J. A., Morin, S. F., & Grant, I. (2009). Psychiatric context of acute/early HIV infection. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: IV. AIDS and Behavior. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9585-3.

Brenner, B. G., Roger, M., Routy, J.-P., Moisi, D., Ntemgwa, M., Matte, C., et al. (2007). High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 195, 951–959. doi:10.1086/512088.

Cates, W., Jr, Chesney, M. A., & Cohen, M. S. (1997). Primary HIV infection—a public health opportunity. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1928–1930. doi:10.2105/AJPH.87.12.1928.

Colfax, G. N., Buchbinder, S. P., Cornelisse, P. G., Vittinghoff, E., Mayer, K., & Celum, C. (2002). Sexual risk behaviors and implications for secondary HIV transmission during and after HIV seroconversion. AIDS, 16, 1529–1535. doi:10.1097/00002030-200207260-00010.

Flanigan, T., & Tashima, K. T. (2001). Diagnosis of acute HIV infection: It’s time to get moving! Annals of Internal Medicine, 134, 75–77.

Gray, R. H., Wawer, M. J., Brookmeyer, R., Sewankambo, N. K., Serwadda, D., Wabwire-Mangen, F., et al. (2001). Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet, 357, 1149–1153. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2.

Hightow, L. B., MacDonald, P. D., Pilcher, C. D., Kaplan, A. H., Foust, E., Nguyen, T. Q., et al. (2005). The unexpected movement of the HIV epidemic in the Southeastern United States: Transmission among college students. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 38(5), 531–537.

Kalichman, S. C., Rompa, D., Cage, M., DeFonzo, K., Simpson, D., Austin, J., et al. (2001). Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 21, 84–92. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00324-5.

Kassutto, S., & Rosenberg, E. S. (2004). Primary HIV type 1 infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 38, 1447–1453. doi:10.1086/420745.

Kelly, J. A., Morin, S. F., Remien, R. H., Steward, W. T., Higgins, J. A., Seal, D. W., Dubrow, R., Atkinson, J. H., Kerndt, P. R., Pinkerton, S. D., Mayer, K. H., & Sikkema, K. J. (2009). Lessons learned about behavioral science and acute/early HIV infection. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: V. AIDS and Behavior, this issue.

Koopman, J. S., Jacquez, J. A., Welch, G. W., Simon, C. P., Foxman, B., Pollock, S. M., et al. (1997). The role of early HIV infection in the spread of HIV through populations. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology, 14, 249–258.

Lewis, F., Hughes, G. J., Rambaut, A., Pozniak, A., & Leigh Brown, A. J. (2008). Episodic sexual transmission of HIV revealed by molecular phylodynamics. PLoS Medicine, 5, 3092–3402. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050050.

Marks, G., Crepaz, N., Senterfitt, J. W., & Jannsen, R. S. (2005). Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 39, 446–453. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. (2008). Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services, November 3, 2008. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2009.

Pao, D., Fisher, M., Hue, S., Dean, G., Murphy, G., & Cane, P. A. (2005). Transmission of HIV-1 during primary infection: Relationship to sexual risk and sexually transmitted infections. AIDS, 19(1), 85–90. doi:10.1097/00002030-200501030-00010.

Patel, P., Klausner, J. D., Bacon, O. M., Liska, S., Taylor, M., Gonzalez, A., et al. (2006). Detection of acute HIV infections in high-risk patients in California. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 42, 75–79. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000218363.21088.ad.

Pilcher, C. D., Eron, J. J., Galvin, S., Gay, C., & Cohen, M. S. (2004a). Acute HIV revisited: New opportunities for treatment and prevention. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 113, 937–945.

Pilcher, C. D., Fiscus, S. A., Nguyen, T. Q., Foust, E., Wolf, L., Williams, D., et al. (2005). Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352, 1873–1883. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042291.

Pilcher, C. D., Tien, H. C., Eron, J. J., Jr, Vernazza, P. L., Leu, S. Y., Stewart, P. W., et al. (2004b). Brief but efficient: Acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 189, 1785–1792. doi:10.1086/386333.

Priddy, F. H., Pilcher, C. D., Moore, R. H., Tambe, P., Park, M. N., Fiscus, S. A., et al. (2007). Detection of acute HIV infections in an urban HIV counseling and testing population in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 44, 196–202. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000254323.86897.36.

Quinn, T. C., Brookmeyer, R., Kline, R., Shepherd, M., Paranjape, R., Mehendale, S., et al. (2000). Feasibility of pooling sera for HIV-1 viral RNA to diagnose acute primary HIV-1 infection and estimate HIV incidence. AIDS, 14, 2751–2757. doi:10.1097/00002030-200012010-00015.

Remien, R. H., Higgins, J. A., Correale, J., Bauermeister, J., Dubrow, R., Bradley, M., Steward, W. T., Seal, D. W., Sikkema, K. J., Kerndt, P. R., Mayer, K. H., Truong, H. M., Casey, C. Y., Ehrhardt, A. A., & Morin, S. F. (2009). Lack of understanding of acute HIV infection among newly-infected persons—implications for prevention and public health. The NIMH multisite acute HIV infection study: II. AIDS and Behavior, this issue.

Schacker, T., Collier, A. C., Hughes, J., Shea, T., & Corey, L. (1996). Clinical and epidemiologic features of primary HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 125, 257–264.

Stekler, J., Swenson, P. D., Wood, R. W., Handsfield, H. H., & Golden, M. R. (2005). Targeted screening for primary HIV infection through pooled HIV-RNA testing in men who have sex with men. AIDS, 19, 1323–1325. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000180105.73264.81.

Stekler, J., Sycks, B. J., Holte, S., Maenza, J., Stevens, C. E., Dragavon, J., et al. (2008). HIV dynamics in seminal plasma during primary HIV infection. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 24, 1269–1274. doi:10.1089/aid.2008.0014.

Steward, W. T., Remien, R. H., Higgins, J. A., Dubrow, R., Pinkerton, S. D., Sikkema, K. J., Truong, H. M., Johnson, M. O., Hirsch, J., Brooks, R. A., & Morin, S. F. (2009). Behavior change following diagnosis with acute/early HIV infection—a move to serosorting with other HIV-infected individuals. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: III. AIDS and Behavior, this issue.

Sudarshi, D., Pao, D., Murphy, G., Parry, J., Dean, G., & Fisher, M. (2008). Missed opportunities for diagnosing primary HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 84, 14–16. doi:10.1136/sti.2007.026963.

Truong, H. M., Grant, R. M., McFarland, W., Kellogg, T., Kent, C., Louie, B., et al. (2006). Routine surveillance for the detection of acute and recent HIV infections and transmission of antiretroviral resistance. AIDS, 20, 2193–2197. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000252059.85236.af.

Wawer, M., Gray, R. H., Sewankambo, N. K., Serwadda, D., Li, X., Laeyendecker, O., et al. (2005). Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191, 1403–1409. doi:10.1086/429411.

Weinhardt, L. S., Carey, M. P., et al. (1999). Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: A meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1397–1405. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1397.

Weintrob, A. C., Giner, J., Menezes, P., Patrick, E., Benjamin, D. K., Jr, Lennox, J., et al. (2003). Infrequent diagnosis of primary human immunodeficiency virus infection: Missed opportunities in acute care settings. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163, 2097–2100. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.17.2097.

Yerly, S., Vora, S., Rizzardi, P., Chave, J. P., Vernazza, P. L., Flepp, M., et al. (2001). Acute HIV infection: Impact on the spread of HIV and transmission of drug resistance. AIDS, 15(17), 2287–2292.

Zetola, N. M., & Pilcher, C. D. (2007). Diagnosis and management of acute HIV infection. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 21, 19–48. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2007.01.008.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Funding and Principal Investigators

Primary Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health as supplements to the following AIDS Research Centers:

P30MH062246, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California San Francisco, PI: Stephen F. Morin, PhD (Study Coordinating Center)

P30MH043520, HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, PI: Anke A. Ehrhardt, PhD (Qualitative Data Analysis Center)

P30MH062512, HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center, University of California San Diego, PI: Igor Grant, MD (Mental Health Assessment Center)

P30MH052776, Center for AIDS Intervention Research, Medical College of Wisconsin, PI: Jeffrey A. Kelly, PhD

P30MH058107, Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services, University of California Los Angeles; PI: Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus, PhD.

P30MH062294, Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, Yale University, PI: Michael H. Merson, MD

Additional funding was provided by:

P30AI42853, Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research; PI: Charles C.J. Carpenter, MD

AI43638, Acute Infection and Early Disease Research Program, University of California San Diego, PI: Susan Little, MD.

Steering Committee (Lead Scientists)

Stephen F. Morin, PhD (Protocol Chair)1; Robert H. Remien, PhD (Study Co-PI and Director of Qualitative Research)2; Wayne T. Steward, PhD, MPH (Scientific Coordinator)1; J. Hampton Atkinson, MD3; Robert Dubrow, MD, PhD4; Peter R. Kerndt, MD, MPH5; Kenneth H. Mayer, MD6; David W. Seal, PhD7; Andrew D. Forsyth, PhD (NIMH Project Officer)8

Co-Investigators and Collaborating Scientists

Mark Bradley, MD2; Joseph Becker, MD9; Ronald A. Brooks, PhD10; Curt G. Beckwith, MD6; R. Douglas Bruce, MD, MA9; Corinna Young Casey, PhD3; Michael Chien, MPH5; Jacqueline Correale, MPH2; Dana Dunne, MD9; Jenny A. Higgins, PhD11; Jennifer S. Hirsch, PhD2; Heidi Jenkins, BA12; Mallory O. Johnson, PhD1; Thomas J. Kidder, MSW, LCSW13; Duncan Mackeller, MA, MPH14; Monica Parker, PhD15; Pragna Patel, MD, MPH14; Steven D. Pinkerton, PhD7; Olga Grinstead Resnick, PhD, MPH1; Aaron Roome, PhD16; Kathleen J. Sikkema, PhD17; Timothy Sullivan15; Judith Wethers, MSHSM15; Hong-Ha M. Truong, PhD, MS, MPH1; Apurva Uniyal, MA5; Ofilio R. Vigil, MS3

Project Staff

Deborah Benson3; Alexandra Boeving, PhD4; Robert Ducharme6; Pamela Julian, MPH4; Staeci Morita5; Irma Rodriguez6; Lashawnda Royal5; Ali Stirland, MBChB, MSc5

1Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California San Francisco

2HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University

3HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center, University of California San Diego

4Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, Yale University

5Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Sexually Transmitted Disease Program

6Brown University

7Center for AIDS Intervention Research, Medical College of Wisconsin

8National Institute of Mental Health

9Yale University School of Medicine

10Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services, University of California Los Angeles

11Center for Health and Wellbeing, Princeton University

12Connecticut Department of Public Health STD/TB Program

13Hill Health Center HIV/AIDS Division, New Haven, CT.

14Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Surveillance and Epidemiology

15New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center, Diagnostic HIV Laboratory

16Connecticut Department of Public Health HIV/AIDS Surveillance Program

17Duke University

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerndt, P.R., Dubrow, R., Aynalem, G. et al. Strategies Used in the Detection of Acute/Early HIV Infections. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: I. AIDS Behav 13, 1037–1045 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9580-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9580-8