Abstract

Background/Aims

When visual acuity (VA) is assessed with spatially repetitive stimuli (e.g., gratings) in amblyopes, VA can be markedly overestimated. We evaluated to what extent this also applies to VEP-based objective acuity assessment, which typically uses gratings or checkerboards.

Methods

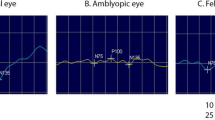

Seventeen subjects with amblyopia (anisometropic and strabismic) participated in the study; decimal VA range of their amblyopic eye covered 0.03–1.0 (1.5–0.0 logMAR). Using the Freiburg Acuity VEP (FrAVEP) method, checkerboard stimuli with six check sizes covering 0.02°–0.4° were presented in brief-onset mode (40 ms on, 93 ms off) at 7.5 Hz. All VEPs were recorded with a Laplacian montage. Fourier analysis yielded the amplitude and significance at the stimulus frequency. Psychophysical VA was assessed with the Landolt-C-based automated Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FrACT).

Results

Test–retest limits of agreement for both FrACT and FrAVEP were ±0.20 logMAR. In all but two dominant eyes and high-acuity amblyopic eyes (VA <0.3 logMAR), FrACT and FrAVEP agreed within the expected limits of ±0.3 logMAR. However, the VEP-based acuity procedure overestimated single Landolt-C acuity by more than 0.3 logMAR in 9 of 17 (53 %) of the amblyopic eyes, up to 1 logMAR. While all subjects had a psychophysical acuity difference >0.2 logMAR between the dominant and amblyopic eye, only three of them showed such difference with the FrAVEP.

Conclusion

Both measurements of visual acuity with the VEP and FrACT were highly reproducible. However, as expected, in amblyopia, acuity can be markedly overestimated using the VEP. We attribute this to the use of repetitive stimulus patterns (checkerboards), which also lead to overestimation in psychophysical measures. The VEP-based objective assessment never underestimated visual acuity, but needs to be interpreted with appropriate caution in amblyopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Katsumi O, Denno S, Arai M, De Lopes Faria J, Hirose T (1997) Comparison of preferential looking acuity and pattern reversal visual evoked response acuity in pediatric patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 235:684–690

Norcia A, Tyler C (1985) Spatial frequency sweep VEP: visual acuity during the first year of life. Vis Res 25:1399–1408

Ghasia F, Brunstom J, Tychsen L (2009) Visual acuity and visually evoked responses in children with cerebral palsy: gross motor function classification scale. Br J Ophthalmol 93:1068–1072

Strasburger H, Remky A, Murray IJ, Hadjizenonos C, Rentschler I (1996) Objective measurement of contrast sensitivity and visual acuity with the steady-state visual evoked potential. Ger J Ophthalmol 5:42–52

Bach M, Maurer JP, Wolf ME (2008) Visual evoked potential-based acuity assessment in normal vision, artificially degraded vision, and in patients. Br J Ophthalmol 92:396–403

Ridder WH 3rd (2004) Methods of visual acuity determination with the spatial frequency sweep visual evoked potential. Doc Ophthalmol 109:239–247

Mackay AM, Bradnam MS, Hamilton R, Elliot AT, Dutton GN (2008) Real-time rapid acuity assessment using VEPs: development and validation of the step VEP technique. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49:438–441

Regan D (1978) Assessment of visual acuity by evoked potential recording: ambiguity caused by temporal dependence of spatial frequency selectivity. Vis Res 18:439–443

Norcia AM, Tyler CW, Hamer RD, Wesemann W (1989) Measurement of spatial contrast sensitivity with the swept contrast VEP. Vis Res 29:627–637

Meigen T, Bach M (1999) On the statistical significance of electrophysiological steady-state responses. Doc Ophthalmol 98:207–232

McBain VA, Robson AG, Hogg CR, Holder GE (2007) Assessment of patients with suspected non-organic visual loss using pattern appearance visual evoked potentials. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 245:502–510

Harter MR, White CT (1970) Evoked cortical responses to checkerboard patterns: effect of check-size as a function of visual acuity. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 28:48–54

Tyler CW, Apkarian P, Levi DM, Nakayama K (1979) Rapid assessment of visual function: an electronic sweep technique for the pattern visual evoked potential. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 18:703–713

Apkarian PA, Nakayama K, Tyler CW (1981) Binocularity in the human visual evoked potential: facilitation, summation and suppression. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 51:32–48

Strasburger H, Rentschler I, Scheidler W (1986) Steady-state pattern VEP uncorrelated with suprathreshold contrast perception. Hum Neurobiol 5:209–211

Bach M, Joost W (1989) VEP vs spatial frequency at high contrast: subjects have either a bimodal or single-peaked response function. In: Kulikowski J, Dickinson C, Murray I (eds) Seeing contour colour. Pergamon Press, Oxford, pp 478–484

Parry NR, Murray IJ, Hadjizenonos C (1999) Spatio-temporal tuning of VEPs: effect of mode of stimulation. Vis Res 39:3491–3497

Heinrich SP (2010) Some thoughts on the interpretation of steady-state evoked potentials. Doc Ophthalmol 120:205–214

Friendly DS, Jaafar MS, Morillo DL (1990) A comparative study of grating and recognition visual acuity testing in children with anisometropic amblyopia without strabismus. Am J Ophthalmol 110:293–299

Bach M, Strahl P, Waltenspiel S, Kommerell G (1990) Amblyopia: reading speed in comparison with visual acuity for gratings, single Landolt Cs and series Landolt Cs. Fortschr Ophthalmol 87:500–503

Gwiazda JE (1992) Detection of amblyopia and development of binocular vision in infants and children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 3:735–740

Kushner BJ, Lucchese NJ, Morton GV (1995) Grating visual acuity with Teller cards compared with Snellen visual acuity in literate patients. Arch Ophthalmol 113:485–493

Stuart JA, Burian HM (1962) A study of separation difficulty. Its relationship to visual acuity in normal and amblyopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol 53:471–477

Chen SI, Norcia AM, Pettet MW, Chandna A (2005) Measurement of position acuity in strabismus and amblyopia: specificity of the vernier VEP paradigm. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46:4563–4570

Ridder WH, Rouse MW (2007) Predicting potential acuities in amblyopes: predicting post-therapy acuity in amblyopes. Doc Ophthalmol 114:135–145

World Medical Association (2000) Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Am Med Assoc 284:3043–3045

Bach M (1996) The Freiburg Visual Acuity Test: automatic measurement of visual acuity. Optom Vis Sci 73:49–53

Bach M, Dakin SC (2009) Regarding “Eagle-eyed visual acuity: an experimental investigation of enhanced perception in autism”. Biol Psychiatry 66:e19–e20 author reply e23–24

Tavassoli T, Latham K, Bach M, Dakin SC, Baron-Cohen S (2011) Psychophysical measures of visual acuity in autism spectrum conditions. Vis Res 51:1778–1780

Loumann Knudsen L (2003) Visual acuity testing in diabetic subjects: the decimal progression chart versus the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 241:615–618

Wesemann W (2002) Visual acuity measured via the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FVT), Bailey Lovie chart and Landolt Ring chart. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 219:660–667

Schulze-Bonsel K, Feltgen N, Burau H, Hansen L, Bach M (2006) Visual acuities “hand motion” and “counting fingers” can be quantified with the Freiburg visual acuity test. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47:1236–1240

Lieberman HR, Pentland AP (1982) Microcomputer-based estimation of psychophysical thresholds: the best PEST. Behav Res Method Instrum 14:21–25

Treutwein B (1995) Adaptive psychophysical procedures. Vis Res 35:2503–2522

Bach M (2007) Freiburg evoked potentials. http://www.michaelbach.de/ep2000.html. Accessed 19 Aug 2013

Mackay A, Bradnam M, Hamilton R (2003) Rapid detection of threshold VEPs. Clin Neurophysiol 114:1009–1020

Fahle M, Bach M (2006) Basics of the VEP. In: Heckenlively J, Arden G (eds) Principles and practice of clinical electrophysiology of vision. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 207–234

Bach M, Meigen T (1999) Do’s and don’ts in Fourier analysis of steady-state potentials. Doc Ophthalmol 99:69–82

Zhou P, Zhao MW, Li XX, Hu XF, Wu X, Niu LJ, Yu WZ, Xu XL (2008) A new method of extrapolating the sweep pattern visual evoked potential acuity. Doc Ophthalmol 117:85–91

R Development Core Team (2006) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org. Accessed 26 Oct 2013

Bland JM, Altman DG (1999) Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res 8:135–160

Bach M (2007) The Freiburg visual acuity test: variability unchanged by post hoc re-analysis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 245:965–971

Holopigian K, Bach M (2010) A primer on common statistical errors in clinical ophthalmology. Doc Ophthalmol 121:215–222

Haase W, Hohmann A (1982) A new test (C-test) for quantitative examination of crowding with test results in amblyopic and ametropic patients (author’s transl). Klin Monatsblätter Für Augenheilkd 180:210–215

Gräf MH, Becker R, Kaufmann H (2000) Lea symbols: visual acuity assessment and detection of amblyopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 238:53–58

Mayer DL (1986) Acuity of amblyopic children for small field gratings and recognition stimuli. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 27:1148–1153

Katz B, Sireteanu R (1989) The Teller acuity card test: possibilities and limits of clinical use. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 195:17–22

Gräf M, Dietrich H (1994) Objective vernier acuity testing in adults, children and infants. Possibilities and limits of a new method. Klin Monatsblätter Für Augenheilkd 204:98–104

Hess RF, Campbell FW, Greenhalgh T (1978) On the nature of the neural abnormality in human amblyopia; neural aberrations and neural sensitivity loss. Pflüg Arch 377:201–207

Gräf M (1998) Objective assessment of minimum visual acuity by suppression of optokinetic nystagmus. Klin Monatsblätter Für Augenheilkd 212:196–202

Graf MH (1999) Information from false statements concerning visual acuity and visual field in cases of psychogenic visual impairment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 237:16–20

Heinrich SP, Marhöfer D, Bach M (2010) “Cognitive” visual acuity estimation based on the event-related potential P300 component. Clin Neurophysiol 121:1464–1472

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

No commercial relationship for authors Y.W., S.P.H., C.P.-B., and A.F. Author M.B. reports licensing the FrAVEP paradigm to a company through the Freiburg University technology transfer center.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wenner, Y., Heinrich, S.P., Beisse, C. et al. Visual evoked potential-based acuity assessment: overestimation in amblyopia. Doc Ophthalmol 128, 191–200 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-014-9432-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-014-9432-3