Abstract

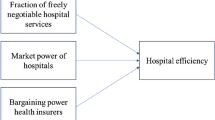

We examine the impact of competition on outcome and process indicators of hospital quality. While earlier literature on the relationship between competition and hospital quality mainly focused on outcome indicators, we argue that the inclusion of process indicators in the analysis can provide supplementary information about the effect of competitive pressure on hospitals’ incentives. In particular, these indicators are less noisy than outcome indicators and are important as a management tool. Our panel dataset covers all Dutch general and academic hospitals in the period 2004–2008, during which the transparency of hospital quality information increased substantially due to the disclosure of hospitals’ quality indicators. We find that competition among hospitals located within the hospital catchment area explains differences in several process indicators, but fails to explain differences in outcome indicators. The results suggest that hospitals facing more competition organize diagnostic processes more efficiently; however, they have more operation cancellations at short notice and more delays of hip fracture injury operations for elderly patients. This suggests that competition affects the allocation of hospital personnel efforts even when outcomes have not been affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This idea is in line with contracting practices of Dutch insurers in 2009. According to NZa (2010, p.33), contracts between insurers and hospitals typically include agreements on structure and process indicators, rather than on outcome indicators; and only few insurers have considered agreements on outcome indicators. Process indicators have also been used in health economics literature focusing on specific health care fields, such as primary care (Jürges and Pohl 2012).

Our analysis does not cover four specialized hospitals: one eye-hospital (Oogziekenhuis Rotterdam), two orthopaedic clinics (Sint Maartensklinieken Nijmegen/Woerden) and one oncological hospital (Antoni van Leeuwenhoek ziekenhuis Amsterdam).

See, e.g. the major independent Dutch website assisting consumers in their hospital choice, www.kiesbeter.nl, as well as the website of one of the largest insurers, www.cz.nl.

As we observe discrete data on the disclosure of information, we cannot use a Mixed Proportional Hazard framework. Instead, we model the disclosure decision using a Logit specification with proportional random effects.

As a robustness check, we have tested whether the effect of regional competition stays the same on the subsample of 2008, for which the data on quality are complete. This was done by including the interaction term of competition with the dummy for the year 2008 in regressions and performing a t test on the respective coefficients. This yielded insignificant outcomes.

For quality outcome measures that are close to 100 %, the normality assumption may be restrictive. In order to test for this, we estimated our model using a Logit specification for the quality outcomes. The estimation results were very similar to those of our benchmark model.

These undesirable effects occur when the sample of patients that is used to measure the indicator does not represent the hospital population for which the indicator was relevant, or when the group of patients is small and an outlier has a large effect on the average. These problems are well known in the literature on measuring hospital quality. See, e.g., Dimick et al. (2004) and Zaslavsky (2001).

The results on decubitus should be interpreted with care for the following reasons. First, the definitions of these indicators make no distinction in degrees of decubitus, therefore, these indicators would not pick up effects associated with improvement of the degree of decubitus. Second, we cannot exclude the possibility that not all hospitals used the same definition in this period (Houwing et al. 2007). The result on decubitus prevalence is more significant, than the result on decubitus incidence, since decubitus prevalence is measured over a larger group of patients. See the definition of these indicators in “Appendix 1”.

Both income variables turned out to be insignificant for all quality measures. A simple explanation for the latter effect is that the Netherlands is characterized by a relatively even income distribution across the geographic areas, which are our relevant unit of analysis. Indeed, a more detailed analysis of the income variables confirms that their standard deviations within catchment areas are 2–3 times larger than between catchment areas. Roughly speaking, this means that 80 to 85 % of the total variance in income variables can be attributed to within-catchment area effects. The age variable was significant only for the HbA1c-test frequency indicator for diabetic patients, and insignificant for all other variables. The inclusion of all the three variables did not change the other results.

Exceptions are the indicators of decubitus. The standard deviation of an indicator can increase with the size of the sample, if an indicator was initially available only for a targeted very homogeneous group of patients, but later become to be measured for a more diverse group of patients.

References

Abbring, J. H., & Van den Berg, G. J. (2003). The nonparametric identification of treatment effects in duration models. Econometrica, 71, 517–1491.

Baker, G. (2000). The use of performance measures in incentive contracting. The American Economic Review, 90(2), 415–420.

Blank, J., Haelermans, C., Koot, P., & van Putten-Rademaker, O. (2008). Schaal en Zorg: een internationale vergelijking. The Netherlands: Schaal en Zorg Achtergrondstudies.

Bloom, N., Propper, C., Seiler, S., & Van Reenen, J., (2010). The impact of competition on management quality: Evidence from public hospitals. Discussion paper 983. London: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

Board, O. (2009). Competition and disclosure. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 57(1), 197–213.

Cooper, Z., Gibbons, S., Jones, S., & McGuire, A. (2010). Does hospital competition improve efficiency? An analysis of the recent market-based reforms to the English NHS. Discussion paper 988. London: Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

Courty, P., & Marschke, G. (2008). A general test for distortions in performance measures. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 428–441.

Dimick, J. B., Welch, H. G., & Birkmeyer, J. D. (2004). Surgical mortality as an indicator of hospital quality. The problem with small sample size. The Journal of the Americal Medical Association, 292, 847–851.

Donabedian, A. (1966). Evaluating the quality of medical care. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 44(3), 166–206.

Dranove, D., & Satterthwaite, M. (2000). The industrial organization of health care markets. In A. Culyer & J. P. Newhouse (Eds.), Handbook of health economics (Vol. 1B, pp. 1094–1139). New York: North-Holland.

Espinosa, W. E., & Bernard, D. M. (2005). Hospital finances and patient safety outcomes. Inquiry, 42(1), 60–72.

Filistrucchi, L., & Ozbugday, F. C. (2012). Mandatory quality disclosure and quality supply: Evidence from German hospitals. TILEC discussion paper 2012–031.

Gaynor, M. (2006). Competition and quality in health care markets? Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics, 2, 441–508.

Gaynor, M., Propper, C., & Moreno-Serra, R. (2010). Death by market power: Reform, competition and patient outcomes in the national health service. NBER working papers, W16164.

Gowrisankaran, G., & Town, R. (2003). Competition, payers and hospital quality. Health Services Research, 38, 1403–1422.

Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1980). Disclosure laws and takeover bids. Journal of Finance, 35, 323–334.

Hausman, J. (2001). Mismeasured variables in econometric analysis: Problems from the right and problems from the left. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 57–67.

Heckman, J., & Singer, B. (1984). A method for minimizing the impact of distributional assumptions in econometric models for duration data. Econometrica, 52(2), 271–320.

Houwing, R. H., Koopman, E. S. M., & Haalboom, J. R. E. (2007). Vochtigheidsletsel is gewone decubitus. Medisch Contact, 3, 103–105.

IGZ (Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg). (2008). Het resultaat telt 2007. Prestatieindicatoren als onafhankelijke graadmeter voor de kwaliteit van in ziekenhuizen verleende zorg. Den Haag: IGZ.

Jin, G. Z. (2005). Competition and disclosure incentives: An empirical study of HMOs. The RAND Journal of Economics, 36(1), 93–112.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Truthful disclosure of information. Bell Journal of Economics, 13, 36–44.

Jürges, H., & Pohl, V. (2012). Medical guidelines, physician density, and quality of care: Evidence from German SHARE data. European Journal of Health Economics, 13(5), 635–649.

Kessler, D. P., & McClellan, M. B. (2000). Is hospital competition socially wasteful? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 577–615.

Levin, D., Peck, J., & Ye, L. (2009). Quality disclosure and competition. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 57(1), 167–196.

Lilford, R. J., Brown, C. A., & Nicholl, J. (2007). Use of process measures to monitor the quality of clinical practice. British Medical Journal, 335(7621), 648–650.

Mant, J. (2001). Process versus outcome indicators in the assessment of quality in health care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 13(6), 475–480.

Murillo-Zamorano, L. R., & Petraglia, C. (2011). Technical efficiency in primary health care: Does, quality matter? The European Journal of Health Economics, 12, 115–125.

NZa (Nederlandse Zorgauthoriteit). (2004). Lijst met ziekenhuisproducten met vrije prijzen vastgesteld. Press release, January 19, 2004.

NZa (Nederlandse Zorgauthoriteit). (2009). Monitor Ziekenhuiszorg 2009, Tijd voor reguleringszekerheid. Utrecht, the Netherlands.

NZa (Nederlandse Zorgauthoriteit). (2010). Monitor Medisch Specialistische zorg 2010, Tussenrapportage. Utrecht, the Netherlands.

OECD. (2009). OECD health data: Frequently requested data.

Propper, C., Wilson, D., & Burgess, S. (2006). Extending choice in English health care: The implications of the economic evidence. Journal of Social Policy, 35, 537–557.

Propper, C., Burgess, S., & Green, K. (2004). Does competition between hospitals improve the quality of care? Hospital death rates and the NHS internal market. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7–8), 1247–1272.

Propper, C., Burgess, S., & Gossage, D. (2008). Competition and quality: Evidence from the NHS internal market 1991–9. Economic Journal, 118, 138–170.

Rubin, H., Pronovost, P., & Diette, G. (2001). The advantages and disadvantages of process-based measures of health care quality. International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 13(6), 469–474.

Sari, N. (2002). Do competition and managed care improve quality? Health Economics, 11, 571–584.

van den Berg, J. M., Haechk, J., van der Kolk, M., & den Ouden, L. (Ed.) (2009). (Toe)zicht op ziekenhuizen. vijf jaar presteren met indicatoren. De Tijdstroom Publishers: The Netherlands.

Volpp, K. G., Williams, S. V., Walsfogel, J., Silber, J. H., Schwartz, J. S., & Pauly, M. V. (2003). Market reform in New Jersey and the effect on mortality from acute myocardial infarction. Health Services Research, 38(2), 515–533.

Zaslavsky, A. M. (2001). Statistical issues in reporting quality data: Small samples and case mix variation. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 13(6), 481–488.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ali Aouragh for valuable research assistance, particularly when preparing the data set for the analysis. Furthermore, we would like to thank Pieter van Bemmel, Paul de Bijl, Rudy Douven, Jeroen Geelhoed, Rein Halbersma, Xander Koolman, Misja Mikkers, Kees Molenaar, Ellen Magenheim, Esther Mot, Erik Schut, and Adriaan Soetevent for their comments and suggestions on earlier versions, and to the participants of the Amsterdam Center of Law and Economics (ACLE, Amsterdam University) conference ‘Innovation, information and competition’ and the 3rd Biennial Conference of the American Society of Health Economists (ASHE) ‘Health, Healthcare and Behavior’ for discussion. Finally, we thank to the anonymous referees of this paper for their comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Description of the Basis Data Set

Below, we provide a more detailed description on the indicators included in the analysis. Table 10 at the end of the section gives an overview of the complete questionnaire and data availability.

1.1 Cardiology

In the data set, the quality in cardiology is reflected by mortality rates from acute myocardinfarct (AMI) and readmissions for heart failures. Prior to 2007, the data on cerebrovascular accident (CVA) were collected as well, but the definition of this indicator has changed over the years. Therefore, we do not include CVA indicators in the analysis.

The data on readmissions for heart failure are available for all years, split by age groups: under 75 and above 75 years. Here we use an aggregated indicator that covers all ages. The AMI-mortality rates also cover all ages. In the first 3 years, hospitals were asked to report 30-day AMI mortality rates, but if that figure was not readily available, it was sufficient to report hospital AMI-mortality rates (i.e. mortality during hospital admissions). Most hospitals report the second indicator, some report both, and some report only the first indicator. Both indicators were included in the questionnaire of 2007, whereas only the hospital AMI-mortality rate was requested in 2008. Based on the data of 2007, for which both indicators are available, the difference between the two is very small. Therefore, in addition to regressions with hospital AMI mortality and 30-day AMI-mortality, we also consider a ‘pooled AMI-indicator’, which takes the value of 30-day AMI mortality where that was available, and otherwise, takes the value of hospital AMI mortality. Although the results with respect to quality levels measured by the pooled indicator should be interpreted with care, the indicator provides a correct picture on disclosure of AMI-mortality.

1.2 Unplanned Reoperations

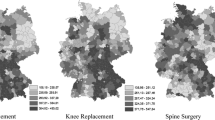

Hospitals report the number of operations as well as the number of unplanned reoperations. The availability of indicators depends on the year of the questionnaire. In particular, the data were reported consistently either at the overall hospital level (in 2004–2005), or for some types of operations (hernia in 2005–2006 and colorectal operations in 2006–2008).

1.3 Decubitus

Decubitus prevalence (share of patients with decubitus at a particular moment in time) and incidence (share of patients with decubitus within a certain relatively homogeneous group of patients, hip fracture patients in this case) show the quality of nursing in the hospital. These data were collected in each year of the questionnaire aggregated over degrees 2–4 of decubitus.

1.4 Post-operation Pain

Post operation pain reflects the quality as experienced by patients. Different definitions of the pain score were used in 2004–2006 (pain score below 4) and in 2007–2008 (pain score above 7). Therefore, we include three separate indicators on pain in the analysis: share of patients in the hospital recovery room who were asked about their pain on a regular basis, share with a pain score below 4, share with a pain score below 7.

1.5 Cancelled Operations

This indicator accounts for cancellations of planned operations made at short notice (\(<\)24 h in advance) and characterizes the quality of logistic processes. Both hospitals and patients can sometimes cancel operations. The number of operations cancelled by hospital is typically two or three times larger than the number of cancellations by patients. According to the Dutch Health Care Inspectorate, the inclusion of patient cancellations is important as well, since a patient is less likely to cancel if the hospital gives him a timely notice before the operation. Hence, we use the cumulative percentage of cancellations in the analysis.

1.6 Hip Fracture

Patients with hip fracture injuries operated within 1 day usually have better outcomes. Especially for elderly patients, the chance on healthy life after this operation depends on the time within which the patient has been operated. Therefore, the quality is measured by the share of patients aged 65+ operated within 1 day. This indicator is available for all years. The split by degree (1–2 and 3–5) is available in some cases, but not always, especially in the first years of the questionnaire. Therefore, we use cumulative figures for degrees 1–5.

1.7 Diabetes Mellitus

Regular control procedures for diabetic patients, such as HbA1c-level tests and fundoscopies, allow doctors to reveal problems and timely prescribe medicines to maintain the health of patients. Therefore, the frequency of these checks can be an important process indicator on diabetes. We include data on the frequency of HbA1c-level tests and fundoscopy procedures.

1.8 Mamma Tumor

The percentage of test outcomes that are ready within 5 days reflects the policlinic quality of the hospital. This indicator was collected in 2004–2006.

Appendix 2: Relative Magnitude of the Effect of Competition on Quality

See Table 11.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bijlsma, M.J., Koning, P.W.C. & Shestalova, V. The Effect of Competition on Process and Outcome Quality of Hospital Care in the Netherlands. De Economist 161, 121–155 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-013-9203-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-013-9203-7