Abstract

This paper deals with the new mineral feed additives with Cu produced in a biosorption process from a semi-technical scale. The natural biomass of edible microalga Spirulina sp. was enriched with Cu(II) and then used as a mineral supplement in feeding experiments on swine to assess its nutrition properties. A total of 24 piglets divided into two groups (control and experimental) were used to determine the bioavailability of a new generation of mineral feed additives based on Spirulina maxima. The control group was feed using traditional inorganic supplements of microelements, while the experimental group was fed with the feed containing the biomass of S. maxima enriched with Cu by biosorption. The apparent absorption was 30 % (P < 0.05) higher in the experimental group. No effect on the production results (average daily feed intake, average daily gain, feed conversion ratio) was detected. It was found that copper concentration in feces in the experimental group was 60 % (P < 0.05) lower than in the control group. The new preparation—a dietary supplement with microelements produced by biosorption based on biomass of microalgae S. maxima—is a promising alternative to currently used inorganic salts as the source of nutritionally important microelements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been concern about the accumulation of minerals in the environment, especially copper (Cu) (Dach and Starmans 2005; Zielińska et al. 2009). Pig diets are usually supplemented with Cu in a dose that sometimes largely exceeds the physiological requirements. Most of the dietary supply is excreted. Manure may contain high amounts of Cu (Jondreville et al. 2003) which has the negative environmental impact. An increasing problem associated with intensive swine production is the concentration of swine manure. Despite its fertilizer value, a certain risk of contamination exists. In some areas, swine manure is collected in pits and spread on agriculture land as slurry using tank wagons (Duffera et al. 1999).

Trace minerals have traditionally been supplemented to livestock diets as inorganic salts that have been reported to have low bioavailability (Chowdhury et al. 2004; Miles and Henry 2000). One of the remarkable effects of high level of copper sulfate (CuSO4·5H2O) in diets for poultry is the gizzard erosion (Chowdhury et al. 2004; Miles and Henry 2000). Improvement of Cu availability may be achieved by providing dietary sources of these microelements in chelated or complexed form, that have shown to be more available form (McDowell 2003). There are various types of organic trace minerals on the market: complexes, amino acid chelates and proteinates (Spears et al. 2004). Amino acid chelates are reported to have significantly higher absorption rates from the intestine as compared to soluble inorganic metal salts (Brady et al. 1978; Ashmead 1985; Ashmead and Zunino 1993; Baker and Ammerman 1995; Bovell-Benjamin et al. 2000). At the same time, it was found that Cu–methionine chelate might carry all the acidic nature of the reactants and therefore cause gizzard erosion, since is manufactured by reacting CuSO4·5H2O with methionine. Copper ions are known to be a very strong catalyst (Chowdhury et al. 2004; Miles and Henry 2000).

Microalgae have been long valued as food and feed. Algae were also considered as a source of essential bioactive compounds for organisms. They provide nearly all essential vitamins (A, B1, B2, B6, B12, C, E, nicotinamide, biotin, folic acid, and panthenoic acid), polyunsaturated fatty acids (GLA, AA, EPA, DHA) and pigments, such as β-carotene or astaxanthin (Spolaore et al. 2006; Dufosse et al. 2005; Marquez-Rocha et al. 1993, 1995). The microalgal industry has gained importance due to its utilization in different field of biotechnological process during the last three decades (Spolaore et al. 2006; Borowitzka 1999; Ohira et al. 2010). Their biosorption abilities were investigated thoroughly (Chojnacka et al. 2004; Abu Al-Rub et al. 2006).

Biosorption is known as selective and effective method of removing pollutants from waste water (Kadukova and Vircikova 2005; Donmez et al. 1999; Aksu 2001). In this study, the mentioned process was applied as technique of binding metal ions to the biomass of microalgae which are nutritionally significant in animals (Zielińska and Chojnacka 2009).

The process of binding microelements to the biomass is based on the ability of biological materials to bind metal ions by either metabolically mediated or purely physico-chemical pathways of uptake (Oporto et al. 2006). Because of negative surface charge and membrane composition, microalgae are natural adsorbents of metal ions (Kargi and Cikla 2006). Cell walls of microalgae, consist mainly of polysaccharides, proteins and lipids and contains many functional groups (such as carboxylate, hydroxyl, thiol, sulfonate, phosphate, amino and imidazole groups) that can form coordination complexes with metal cations (Gong et al. 2005; Yan and Pan 2002) and these functional groups are able to interact with metal ions in an aqueous solution (Saygideger et al. 2005).

The aim of this paper was to evaluate the availability of new generation of mineral feed additives based on microalgae. Spirulina maxima biomass that was enriched with Cu(II) by biosorption and then, used as a mineral supplement in feeding experiments on swine to assess its nutritional properties.

Material and methods

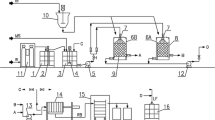

The microalga Spirulina maxima was cultivated in a stirred tank reactor (dimensions 1.12 m × 3.6 m) with a capacity 10 m3, covered by a glasshouse, equipped with the biomass separation system (six bag filters, average pore size 6 μm, Desjoyaux Co, Ltd.), mixing system (pumps) and six lamps (300 W Astral Pool, Poland). S. maxima was obtained from the Culture Collection of Algal Laboratory (CCALA) Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. Microalga was cultivated in the Schlösser (1982) medium, prepared with technical grade reagents.

Biosorption experiments

The biomass of S. maxima was enriched with copper (II) ions via biosorption. The enrichment processes was performed in containers containing 45 L of metal ions solution at ambient temperature in tap water. The solutions were prepared by dissolving appropriate amounts of inorganic salt CuSO4·5H2O admitted for using as a source of Cu(II) in animal diets (from POCH, Gliwice, Poland) (Feeding Standards for Poultry and Swine 2005). The contact time was 2 h as determined previously in kinetic experiments (Michalak et al. 2007). After this time, enriched biomass was separated on a filter with 6 μm pore diameter, dried at 50 °C and ground. Initial concentration of metal ions in the solution was C 0 300 mg L−1. pH of the solution was adjusted with NaOH/HCl to pH 5. The biomass concentration was 1 g of dry mass L−1.

Feeding experiments

Feed

The standard feed was composed of: wheat, hordeum, canola oil, soybean meal, and specially prepared for each stage of the experiments (starter, grower and finisher) mix diet, similar feed was used elsewhere (Korniewicz et al. 2012) (Tables 1 and 2). The content of nutrients and feed additives is presented in Table 3. The source of vitamins and microelements was a commercially available premix produced by LNB Poland. The experimental group was fed with the same feed but microelements were supplemented by S. maxima enriched with microelements by biosorption.

The enriched biomass of S. maxima via biosorption process was investigated as the source of microelement—Cu(II), Fe(II), and Zn(II). The content of Cu, Fe, and Zn in the biomass after biosorption process was as follows: 30.6, 46.5, and 31.5 mg g−1, respectively. Because biomass enriched with copper also contains also other microelements, Fe and Zn, its content was taken into consideration during planning the experiment. Two experimental groups were distinguished:

-

Group I

The microelements requirement was covered by inorganic salts, Control (C),

-

Group II

The requirement for Cu(II) was covered by S. maxima biomass enriched with copper (Sm–Cu) (100 %),

The requirement for Fe was covered by S. maxima biomass enriched with iron (Sm–Fe) (25.5 %) and 74.5 % with inorganic salt.

The requirement for Zn was covered by S. maxima biomass enriched with zinc (Sm–Zn) (17.3 %) and by inorganic salt (82.7 %).

Leeson and Caston (2008) proved that trace minerals are oversupplied in feed formulations. Assuming the enhanced bioavailability of trace minerals in the form of enriched biomass of S. maxima, dietary levels of Cu at first stage of experiments (starter—where the level of microelement is the highest) were minimized in experimental group to about 50 % in the comparison to the control group (Table 4).

Animals, housing

Dewormed (Dectomax® or Ivomec®) piglets (Big White Polish/Polish White Zwisloucha, dams × Hampshire/Pietrain) (24 pigs, 20.9 ± 2.2 kg) were randomly divided into two groups: 12 pigs in the control group and 12 in the experimental group. The three different feed compositions according to the different nutritional requirements for growth of the animals were used. Piglets in rearing phase (20–40 kg) were fed with the standard starter feed mixture, growers during the first period of fattening (40–65 kg) were fed with the standard grower feed mixture, and finishers in the second period of fattening (65–105 kg) were fed with the standard finisher feed mixture. Nutritional value of feed in specific periods of feeding is presented in Table 1–4. At the end of experiments, after swine reached their final weight, ten randomly chosen porkers were killed to obtain liver and meat (Fig. 1). Slaughter procedure was carried out in the slaughterhouse with the required permits and according to Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development dated 02/04/2004 by the persons entitled to professional slaughter and acceptable methods of slaughter and killing of animals (Polish Journal of Laws 2004.70.643). Approved procedure involves use of electronarcosis and exsanguination of pigs.

The study was performed in individual rearing pens with controlled microclimate (16–18 °C). Feed and water were available semi ad libitum. After the 21st day of feeding with grower feed, six porkers from each of group were separated for 7 days in individual cages and fed with the same feed. The first three 3 days were treated as the preliminary step. In the next 4 days, urine and feces were collected from each animal. Every morning, the amount of not consumed feed was recorded.

Sampling

The feeding experiment was conducted for 87 days and was divided into three series: starter (26 days), grower (31 days), and finisher (30 days), respectively (Fig. 1). After each series, each animal was weighed. On the 87th day, blood was collected. After separation, the concentration of microelements in serum was determined. Blood was sampled from the jugular vein. Before sampling blood, heparin was added to the samples in order to prevent blood coagulation. Muscle (longissimus dorsi muscle) and liver samples were homogenized. All samples with the exception of feed were kept in the freezer for multi-elemental analysis.

Analytical methods

The appropriate mass of biological sample (feed—0.5 g, microalgae biomass—0.5 g, blood—4.0 g, meat (muscle)—0.5 g, urine—4.0 g, feces—0.5 g, liver—0.5 g) materials was digested with 5 mL concentrated—65 % (m m−1) HNO3 suprapur grade from Merck in Teflon vessels (microwave oven Milestone MLS-1200). After mineralization, all samples were diluted to 50 mL. Inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometer with ultrasonic nebulizer (Varian VISTA-MPX ICP-OES, Australia) was used to determine the concentration of elements in algae and in all digested and diluted biological samples, in the Chemical Laboratory of Multielemental Analyses at Wroclaw University of Technology, which is accredited by ILAC-MRA and Polish Centre for Accreditation according to PN-EN ISO/IEC 17025.

Calculations and statistical analyses

Shapiro–Wilk test was used to ensure that the data being used had a normal distribution. Levene's test and Brown–Forsythe test were used to assess the equality of variances in different samples. Significance of differences between the groups was examined with U Mann–Whitney (when the distribution was not normal), Welch (for data that have normal distribution and unequal variance), and t test (for data that have normal distribution and equal variance). Three levels of statistical significance were taken into account—at 0.1, 0.05, and 0.001. Statistical significance at P < 0.1 was regarded as a "trend", while 0.05 and 0.001 showed statistical significance of differences. The arithmetic mean values, standard deviations (SD), and t tests were carried out with the use of computer software Statistica ver. 9.0.

Feed conversion ratio (FCR) was calculated as the average of amount of feed ingested during the experiments divided by weight gain. A new coefficient α was defined to consider the real calculated (from ICP-OES analysis of samples) content of microelements in the feed which considers various doses of microelements in feed and enabled a comparison of bioavailability and was calculated according to the Eq. 1. This parameter is an indirect measure of availability of microelements.

Apparent absorption defined as total intake minus feces excretion of the element, was calculated as the difference between intake and total feces excretion divided by intake (Ammerman 1995).

Results

Pigs performance and animal health were very good in both groups throughout the experiment. No pigs were excluded from the experiment.

Average feed intake, average weight gain and feed conversion ratio

The production performance over all periods is summarized in Table 5. No statistically significant differences were observed. Mineral supplementation in the form of enriched biomass of Spirulina did not affect the organoleptic properties of feed and its utilization (Table 5).

Concentration of microelements in collected samples

The average element concentrations in all collected samples were presented in Table 6. No statistically significant differences between the control and experimental group were observed in concentration of microelements in blood (Fig. 6). In meat, Cr concentration increased by 28 % (P < 0.05). Additionally, concentration of Cu, Mn, and Se increased by 18, 25, and 23 %, respectively (Table 6). In liver, a statistically significant decrease of Zn and Se was found, by 16 % (P < 0.1) and 95 % (P < 0.1), respectively (Table 6). At the same time, an increase of Cr by 54 % was observed. The content of Cu, Fe, Co, Mn, Cr, and Se in feces was lower than in the control group by 63 % (P < 0.001), 8 % (Ns), 9.5 % (P < 0.1), 5.3 % (Ns), 8.5 % (P < 0.05), and 19 % (Ns), respectively (Table 6). Only the content of Zn was higher than the control group by 19 % (P < 0.05). At the same time, the concentration of microelements excreted with urine was higher than the control group: 23 % (Ns) of Cu, 19 % (Ns) of Fe, 340 % (P < 0.001) of Zn, 72 % (P < 0.05) of Co, 190 % (P < 0.05) of Mn, 145 % (P = 0.1) of Cr and 336 % (P < 0.05) of Se (Table 6).

The addition of microelements bound with the biomass of Spirulina caused significant increase of macronutrients excretion in urine, 52 % (P < 0.05) of K, 66 % (P < 0.001) of B, 39 % (P < 0.05) of Mg, and 53 % (P < 0.05) of Na. Additionally, 25 and 47 % decrease of Ca and Ba excretion, respectively, was observed. In feces, the content of Ba decreased by 37 %.

The content of Ca and Ba significantly increased in liver by 59 % (P < 0.01) and 460 % (P < 0.01), respectively. In meat, a decrease was observed for macroelement concentrations, but those differences were not statistically significant. In blood, Ba concentration decreased by 47 % (P < 0.05).

Coefficient α (Table 7) presents the degree of absorption of microelements from the experimental and control diet according to the real concentration of those elements in feed. The α coefficient was higher for copper in the treatment than the control, 73 % (P < 0.05) in blood, 60 % (P < 0.1) in meat, and 76 % (P < 0.05) in liver. Coefficient α for iron in blood and meat was slightly higher, and in the case of liver 11 % (P < 0.1) higher in experimental group. Apparent absorption (Table 8) for Cu was 30 % (P < 0.05) higher in experimental group, while for Zn it was lower by 16 % (P < 0.1) in experimental group.

Discussion

The reasons why absorption of Zn was lower might be: the antagonism with copper or supplementation was not suitable form (zinc was supplied mostly in inorganic form), or both. The best results were obtained for copper, because 100 % was supplemented in the form bound with S. maxima enriched by biosorption process. The additional factor that could result in low availability of zinc was strong antagonism Cu–Zn and Fe–Zn. In Fig. 1, the correlation between ratio of α experimental/α control and % of covered demand on microelements by enriched S. maxima was presented. The ratio α experimental/α control expresses absorption of microelement in experimental group in comparison with the control group. To reach better absorption of microelement, it is advised to introduce the microelements in biological form, such as S. maxima enriched with microelement via biosorption process.

This study investigated the ways to minimize the effects of excreted Cu on the environment. Intensive animal breeding is considered to be a serious obstacle to sustainable development. Cu and Zn are often oversupplied in animal diets because they are used as growth promoters or because large safety margins are applied as a result of low bioavailability. Consequently, manure is highly concentrated in these elements, which may concentrate in top soil and cause toxicity to plants and microorganisms (Jondreville et al. 2003). Absorption rates may range from 0–99.5 % depending on the source as well as a host of other factors. It is very important to reduce metals load in manure by lowering the influx through animal feed. Application of highly bioavailable, bio-metallic feed additives based on microalgal biomass is one of the means to limit this environmental risk. In this paper, it was shown that by utilization of new biological feed supplements based on Spirulina enriched with microelements by biosorption, it was possible to reduce by 60 % excretion of copper in feces. At the same time, no effect on production results (BW, ADWG, ADFI, FCR) was observed.

The new mineral feed additives based on microalgae biomass can compete with other biological forms of microelements currently used. There are four types of organic supplements with microelements available: amino acid complex, amino acid chelates, polysaccharide complex, and proteinate (Grela and Rudnicki 2007; Murphy 2009). The complexes and chelates of microelements with amino acids would be four times more concentrated than the microelements bound with the biomass of algae. On the other hand, it is better to use less concentrated material for better distribution of mineral feed additives in the feed. Additionally, literature reports that the use of traditional inorganic sources of micronutrients causes oxidation of vitamins (Marchetti et al. 2000) and perforation of digestive tract (Chowdhury et al. 2004).

Bio-metallic feed additives from microalgae with designed composition are proposed to be a solution to problems with increasing accumulated quantities of trace elements in the environment. Application of this kind of new generation of bio-metallic feed additives would supply microelements in a form highly bioavailable to animals and would reduce amount of microelements of transit character used as supplements in animal feed.

According to the Directive of Polish Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development concerning the maximum acceptable levels of undesirable substances in animal feed is 2 mg kg−1 for arsenic, 10 mg kg−1 cadmium, and 1 mg kg−1 lead. The levels of toxic elements in the diet of the experimental and in the control group were below the acceptable levels.

Abbreviations

- ADFI:

-

Average daily feed intake

- APFI:

-

Average periodical feed intake

- ADWG:

-

Average daily weight gain

- APWG:

-

Average periodical weight gain

- BW:

-

Body weight

- EC:

-

Element content/concentration

- FCR:

-

Feed conversion ratio

References

Abu Al-Rub FA, El-Naas MH, Ashour I, Al-Marzouiqi M (2006) Biosorption of copper on Chlorella vulgaris from single binary and ternary metal aqueous solution. Process Biochem 41:457–464

Aksu Z (2001) Equilibrium and kinetic modeling of cadmium(II) biosorption by C. vulgaris in a bath system: effect of temperature. Sep Purification Technol 21:285–294

Ammerman CB (1995) Methods for estimation of mineral bioavailability. In: Ammerman CB, Baker DH, Lewis AJ (eds) Bioavailability of nutrients for animals: amino acids, minerals, vitamins. Academic, London, pp 83–94

Ashmead HD (1985) Intestinal absorption of metal ions and chelates. Charles CT, Springfield IL

Ashmead HD, Zunino H (1993) Minerals in animal health. In: Ashmead HD (ed) The role of amino acid chelates in animals nutrition. Noyes, USA, pp 21–46

Baker DH, Ammerman CB (1995) Copper bioavailability. In: Ammerman CB, Baker DH, Lewis AJ (eds) Bioavailability of nutrients for animals: amino acids, minerals, vitamins. Academic, London, pp 127–156

Borowitzka MA (1999) Commercial production of microalgae: ponds, tanks, tubes and fermenters. J Biotechnol 70:313–321

Bovell-Benjamin AC, Viteri FE, Allen LH (2000) Iron absorption from ferrous bisglycinate and ferric triglycinate in whole maize is regulated by iron status. Am J Clin Nutr 71:1563–1569

Brady PS, Ku PK, Ullrey DE, Miller ER (1978) Evaluation of an amino acid-iron chelatehematinic for the baby pig. J Anim Sci 47:1135

Chojnacka K, Chojnacki A, Górecka H (2004) Trace element removal by Spirulina sp. from copper smelter and refinery effluents. Hydrometallurgy 73:147–153

Chowdhury SD, Paik IK, Namkungb H, Lim HS (2004) Responses of broiler chickens to organic copper fed in the form of copper–methionine chelate. Anim Feed Sci Technol 115:281–293

Dach J, Starmans D (2005) Heavy metals balance in Poland and Dutch agronomy: actual state and previsions for the future. Agric Ecosyst Environ 107:309–316

Donmez GC, Aksu Z, Ozturk A, Kutusal T (1999) A comparative study on heavy metal biosorption characteristics of some algae. Process Biochem 34:885–892

Duffera M, Robarage WP, Mikkelsen RL (1999) Estimating the availability of nutrients from processed swine lagoon solids through incubation studies. Bioresourc Technol 70:261–268

Dufosse L, Galaup P, Yaron A, Arad SM, Blanc P, Murthy KNC, Ravishankar GA (2005) Microorganisms and microalgae as sources of pigments for food use: a scientific oddity or an industrial reality? Trends Food Sci Technol 16:389–406

Feeding Standards for Poultry and Swine, Polish Academy of Sciences (2005) Institute of Animal Physiology and Feeding, Warsaw

Gong R, Ding Y, Liu H, Chen Q, Liu Z (2005) Lead biosorption and desorption by intact and pretreated Spirulina maxima biomass. Chemosphere 58:125–130

Grela ER, Rudnicki K (2007) Chelated minerals in swine nutrition. Livestock 11:75–79

Jondreville C, Revy PS, Dourmand JY (2003) Dietary means to better control the environmental impact of copper and zinc by pigs from weaning to slaughter. Livest Prod Sci 84:147–156

Kadukova J, Vircikova E (2005) Comparison of differences between copper bioaccumulation and biosorption. Environ Int 31:227–232

Kargi F, Cikla S (2006) Biosorption of zinc (II) ions onto powdered waste sludge (PWS): kinetics and isotherms. Enzyme Microb Tech 38:705–710

Korniewicz D, Dobrzański Z, Kołacz R, Hoffmann J, Korniewicz A, Antkowiak K (2012) Effect of various feed phosphates on productivity, slaughter performance and meat quality of fattening pigs. Med Weter 68:353–358

Leeson S, Caston L (2008) Using minimal supplements of trace minerals as a method of reducing trace mineral content of poultry manure. Anim Feed Sci Technol 142:339–347

Marchetti M, DeWayne AH, Tossani N, Marchetti S, Ashmead SD (2000) Comparison of the rates of vitamin degradation when mixed with metal sulphates or metal amino acid chelates. J Food Comp Anal 13:875–884

Marquez-Rocha FJ, Sasaki K, Kakizono T, Nishio N, Nagai S (1993) Growth characteristics of Spirulina platensis in mixotrophic and heterotrophic conditions. J Ferment Bioeng 76:408–410

Marquez-Rocha FJ, Nishio N, Nagai S, Sasaki K (1995) Enhancement of biomass and pigment production during growth of Spirulina platensis in mixotrophic culture. J Chem Tech Biotech 62:159–164

McDowell LR (2003) Minerals in animal and human nutrition. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Michalak I, Zielińska A, Chojnacka K, Matuła J (2007) Biosorption of Cr(III) by microalgae and macroalgae: equilibrium of the process. Am J Agri Biol Sci 2:284–290

Miles RD, Henry PR (2000) Relative mineral bioavailability. Ciênc Anim Bras 1:73–93

Murphy R (2009) Chelates: clarity in the confusion. Feed Inter 30:22–24

Ohira Y, Shimadzu M, Obata E (2010) Effect of temperature on growth and autolysis of blue-green algae, Spirulina platensis. Kagaku Kogaku Ronbunshu 36:188–191

Oporto C, Arce O, Broeck V, Bruggen VB, Vandecasteele V (2006) Experimental study and modeling of Cr(VI) removal from wastewater using Lemna minor. Water Res 40:1458–1464

Saygideger S, Gulnaz O, Istifli ES, Yucel N (2005) Adsorption of Cd(II), Cu(II) and Ni(II) ions by Lemna minor L. effect of physicochemical environment. J Hazard Mater 126:96–104

Schlösser UG (1982) Sammlung von Algenkulturen, Pflanzenphysiologisches Institut der Universität Göttingen. Ber Dt Bot Ges 95:181–276

Spears JW, Kegley EB, Mullis LA (2004) Bioavailability of copper from tribasic copper chloride and copper sulfate in growing cattle. Anim Feed Sci Technol 116:1–13

Spolaore P, Joannis-Cassan C, Duran E, Isambert A (2006) Commercial applications of microalgae. J Biosci Bioeng 101:87–96

Yan H, Pan G (2002) Toxicity and bioaccumulation of copper in three green microalgae species. Chemosphere 49:471–476

Zielińska A, Chojnacka K (2009) The comparision of biosorption of nutritionally significant minerals in single-and multi-mineral systems by the edible microalga Spirulina sp. J Sci Food Agric 89:2292–2301

Zielińska A, Chojnacka K, Simonić M (2009) Sustainable production process of biological mineral feed additives. Am J Appl Sci 6:1093–1105

Acknowledgments

The work was financially supported by Polish National Centre for Research and Development—project nr N R05 0014 10.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Saeid, A., Chojnacka, K., Korczyński, M. et al. Biomass of Spirulina maxima enriched by biosorption process as a new feed supplement for swine. J Appl Phycol 25, 667–675 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-012-9901-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-012-9901-6