Abstract

Objectives

This systematic review sought to collate and synthesize the risk and protective factors for different outcomes of radicalization. We aimed to firstly quantify the effects of all factors for which rigorous empirical data exists, and secondly, to differentiate between factors related to radical attitudes, intention, and behaviors. The goal was to develop a rank-order of factors based on their pooled estimates in order to gain a better understanding of which factors may be most important, and the differential effects on the different outcomes.

Methods

Random effects meta-analysis pooled primarily bivariate effect sizes to calculate pooled estimates for each factor. Meta-regression was used to examine the effects of a range of study-level characteristics, including the effects of using partial effects sizes as supplementary effect sizes where bivariate estimates were unavailable. Subgroup analysis was used to further analyze the extent to which the combining of effect sizes from different sources contributed to heterogeneity and estimate inflation. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was used to identify cases where a single study was a significant source of heterogeneity.

Results

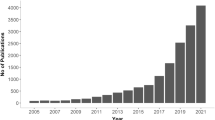

Extensive searches in English, German and Dutch resulted in the screening of more than 10,000 items, and a final inclusion of 57 publications published between 2007 and 2018 from which 62 individual level factors were identified across three radicalization outcomes: attitudes, intentions, and actions. Effect sizes ranged from z − 0.621 to 0.572. The smallest estimates were found for sociodemographic factors, while the largest effect sizes were found for traditional criminogenic and criminotrophic factors such as low self-control, thrill-seeking, and attitudinal factors, with radical attitudes having the largest effect on radical intentions and behaviors.

Conclusions

The most commonly researched factors, sociodemographic factors, have exceptionally small effects, even when effect sizes are derived from bivariate relationships. The finding regarding the effects of radical attitudes on intentions and actions provide empirical support for existing theoretical frameworks. The consistency among the clustering of familiar criminogenic factors within the rank-order could have implications for the development of a more evidence based approach to risk assessment and counter violent extremism policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Putative factors are those factors for which there is evidence to suggest that they play a role, through correlational data operating in the theorized direction, but for which the evidence does not meet the established criteria for classifying them as risk or causal risk factors (Kraemer et al. 1997, 2001). A more extensive description can be found on pages 6–7.

By including confirmed/convicted terrorists as a dependent variable, we make no distinction between violent and non-violent terrorists. However, as some studies compare non-violent and violent terrorist offenders, in such cases, our focus is on the violent offenders. To the best of our knowledge there are no studies comparing non-violent terrorist offenders to samples of non-terrorists.

Samples that included criminals (e.g. Decker and Pyrooz 2019) were included for radical attitudes or intentions since these samples provide variation on the dependent variable. Samples of criminals as a comparison group for terrorists were excluded however since we believe that identifying factors that differentiate terrorist from ordinary criminal offenders represents a different topic of inquiry.

It can also be noted that in recent years Turkey has had an eroding financial, social, and political situation. According to the Sustainable Governance Indicators report for 2018 it has lowest quality of democracy ranking of all OECD and EU countries (Genckaya et al. 2018).

Such as the calculation of correlation coefficients using either bivariate approaches (e.g. Pearson's r), or multivariate regression models, such as linear regression, logistic regression etc.

While most non-English studies are indexed in English, supplementary searches were also conducted in German and Dutch. General searches were also conducted on the Google scholar and search engine to try and identify grey literature.

For example, we contacted renowned experts from the START center at the University of Maryland, as well as the NSCR at the Vrije University in the Netherlands.

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for directing us to two additional studies that met the inclusion criteria and which were not included in our original search results.

We acknowledge that some studies using OLS methods may actually have a discrete, and not truly continuous variable. Nevertheless, whilst these studies' model choice may not have been the most appropriate, we nevertheless adhere to this approach.

Which includes a χ2 significance test.

The minimum number of studies for indicating the presence of publication bias was the number of included studies, n * 5 + 10 (Rosenthal 1979). The Fail-Safe N method has been previously used in systematic reviews where multiple factors and outcomes are explored and for which a relatively small number of studies exist for each factor (e.g. Assink 2017).

The majority of these studies were excluded based on the nature of their dependent variable or the sample. For example, a study by Tol and Akbaba (2016) examined risk factors of membership in Milli Görüş, a legal and non-violent group. Other studies, such as those on foreign fighters, lacked a comparison group (e.g. Verwimp 2016; Bakker and de Bont 2016). We also excluded two additional studies based on the RADIMER dataset for their inability to provide unique effect sizes (Schils and Pauwels 2016; Pauwels and Svensson 2017). We note that Lieven Pauwels, was kind enough to calculate and share bivariate correlations with us for a series of studies that were included. While each of the studies is based on the same dataset, they use different subsamples which vary greatly in size and makeup, and report on different factors (Pauwels and de Waele 2014; Pauwels and Schils 2016).

We would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers who provided us with direction towards two of these studies and who we include here when we refer to experts contacted.

References

*Acevedo GA, Chaudhary AR (2015) Religion, cultural clash, and Muslim American attitudes about politically motivated violence. J Sci Study Relig 54(2):242–260

Agnew R (2016) General strain theory and terrorism. In: LaFree G, Freilich JD (eds) The handbook of the criminology of terrorism. Wiley, Chichester, pp 121–132

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Akers RL, Sellers CS (2004) Criminological theories. Roxbury Publishing, Chicago

Allan H, Glazzard A, Jesperson S, Reddy-Tumu S, Winterbotham E (2015) Drivers of violent extremism: hypotheses and literature. Royal United Services Institute, London

Aloe AM, Tanner-Smith EE, Becker BJ, Wilson DB (2016) Synthesizing bivariate and partial effect sizes. The Campbell Collaboration, Oslo

Altemeyer B, Hunsberger B (1992) Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. Int J Psychol Religion 2(2):113-133

Altemeyer B, Hunsberger B (2004) A revised religious fundamentalism scale: the short and sweet of it. Int J Psychol Religion 14(1):47–54

Altemeyer B, Hunsberger B (2005) Fundamentalism and authoritarianism. Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality 378–393

*Altunbas Y, Thornton J (2011) Are homegrown Islamic terrorists different? Some UK evidence. South Econ J 78(2):262–272

Aly A, Striegher J-L (2012) Examining the role of religion in radicalization to violent Islamist extremism. Stud Confl Terror 35(12):849–862

Assink M (2017) Preventive risk assessment in forensic child and youth care. University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam

Assink M, van der Put CE, Hoeve M, de Vries SL, Stams GJJ, Oort FJ (2015) Risk factors for persistent delinquent behavior among juveniles: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 42:47–61

Assink M, van der Put CE, Meeuwsen MW, de Jong NM, Oort FJ, Stams GJJ, Hoeve M (2019) Risk factors for child sexual abuse victimization: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 145(5):459–489

*Baier D (2010) Kinder und Jugendliche in Deutschland: Gewalterfahrungen, Integration, Medienkonsum; zweiter Bericht zum gemeinsamen Forschungsprojekt des Bundesministeriums des Innern und des KFN: Krim. Forschungsinst, Niedersachen

*Baier D, Manzoni P, Bergmann MC (2016) Einflussfaktoren des politischen Extremismus im Jugendalter. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform 3:171–198

Bakker E, De Bont R (2016) Belgian and Dutch jihadist foreign fighters (2012–2015): characteristics, motivations, and roles in the War in Syria and Iraq. Small Wars Insur 27(5):837–857

Basra R, Neumann PR (2016) Criminal pasts, terrorist futures: European jihadists and the new crime-terror nexus. Perspect Terror 10(6):25–40

Becker MH (2019) When extremists become violent: examining the association between social control, social learning, and engagement in violent extremism. Stud Confl Terror. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2019.1626093

*Berger L (2016) Local, national and global Islam: religious guidance and European Muslim public opinion on political radicalism and social conservatism. West Eur Polit 39(2):205–228

Bernard TJ, Snipes JB, Gerould AL (2010) Integrated theories. In: Vold G (ed) Theoretical criminology, 6th edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 327–345

*Berrebi C (2007) Evidence about the link between education, poverty and terrorism among Palestinians. Peace Econ Peace Sci Public Policy 13(1):1–38

*Besta T, Szulc M, Jaśkiewicz M (2015) Political extremism, group membership and personality traits: who accepts violence? Rev Psicol Soc 30(3):563–585

Bhui KS, Hicks MH, Lashley M, Jones E (2012) A public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization. BMC Med 10(16):1–8

*Bhui K, Warfa N, Jones E (2014) Is violent radicalisation associated with poverty, migration, poor self-reported health and common mental disorders? PLoS ONE 9(3):1–10

*Bhui K, Silva MJ, Topciu RA, Jones E (2016) Pathways to sympathies for violent protest and terrorism. Br J Psychiatry 209(6):483–490

Bondokji N, Wilkinson K, Aghabi L (2017) Trapped between destructive choices: radicalisation drivers affecting youth in Jordan. WANA Institute, Amman

Borenstein M, Cooper H, Hedges L, Valentine J (2009) Effect sizes for continuous data. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC (eds) The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis, vol 2. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 221–235

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR (2011) Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley, Chichester

Borum R (2014) Psychological vulnerabilities and propensities for involvement in violent extremism. Behav Sci Law 32(3):286–305

Bosco FA, Aguinis H, Singh K, Field JG, Pierce CA (2015) Correlational effect size benchmarks. J Appl Psychol 100(2):431

Bowes N, McMurran M (2013) Cognitions supportive of violence and violent behavior. Aggress Violent Beh 18(6):660–665

*Brettfeld K, Wetzels P (2007) Muslime in Deutschland: Integration, Integrationsbarrieren, Religion sowie Einstellungen zu Demokratie, Rechtsstaat und politisch-religiös motivierter Gewalt: Ergebnisse von Befragungen im Rahmen einer multizentrischen Studie in städtischen Lebensräumen. Bundesministerium des Inneren, Berlin

Brockhoff S, Krieger T, Meierrieks D (2015) Great expectations and hard times: the (nontrivial) impact of education on domestic terrorism. J Conflict Resolut 59(7):1186–1215

*Cherney A, Murphy K (2019) Support for terrorism: the role of beliefs in jihad and institutional responses to terrorism. Terror Polit Violence 31(5):1049–1069

Christmann K (2012) Preventing religious radicalisation and violent extremism: a systematic review of the research evidence. Youth Justice Board for England and Wales (YJB), London

Clarke RVG, Newman GR (2006) Outsmarting the terrorists. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport

*Coid JW, Bhui K, MacManus D, Kallis C, Bebbington P, Ullrich S (2016) Extremism, religion and psychiatric morbidity in a population-based sample of young men. Br J Psychiatry 209(6):491–497

Cohen J (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey

Crenshaw M (2007) Explaining suicide terrorism: a review essay. Secur Stud 16(1):133–162

*De Waele M, Pauwels LJ (2016) Why do Flemish youth participate in right-wing disruptive groups? In: Maxson CL, Esbensen FA (eds) Gang transitions and transformations in an international context. Springer, Berlin, pp 173–200

*Decker SH, Pyrooz DC (2019) Activism and radicalism in prison: measurement and correlates in a large sample of inmates in Texas. Justice Q 36(5):787–815

*Delia Deckard N, Jacobson D (2015) The prosperous hardliner: affluence, fundamentalism, and radicalization in Western European Muslim communities. Soc Compass 62(3):412–433

Desmarais SL, Simons-Rudolph J, Brugh CS, Schilling E, Hoggan C (2017) The state of scientific knowledge regarding factors associated with terrorism. J Threat Assess Manag 4(4):180

*Doosje B, van den Bos K, Loseman A, Feddes AR, Mann L (2012) “My in-group is superior!”: susceptibility for radical right-wing attitudes and behaviors in Dutch youth. Negot Confl Manage Res 5(3):253–268

*Doosje B, Loseman A, van den Bos K (2013) Determinants of radicalization of Islamic Youth in the Netherlands: personal uncertainty, perceived injustice, and perceived group threat. J Soc Issues 69(3):586–604

Ellis BH, Abdi S (2017) Building community resilience to violent extremism through genuine partnerships. Am Psychol 72(3):289

*Ellis BH, Abdi SM, Horgan J, Miller AB, Saxe GN, Blood E (2015) Trauma and openness to legal and illegal activism among Somali refugees. Terror Polit Violence 27(5):857–883

*Ellis BH, Abdi SM, Lazarevic V, White MT, Lincoln AK, Stern JE, Horgan JG (2016) Relation of psychosocial factors to diverse behaviors and attitudes among Somali refugees. Am J Orthopsychiatry 86(4):393–408

*Feddes AR, Mann L, Doosje B (2015) Increasing self-esteem and empathy to prevent violent radicalization: a longitudinal quantitative evaluation of a resilience training focused on adolescents with a dual identity. J Appl Soc Psychol 45(7):400–411

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co, Boston

Folk JB, Stuewig JB, Blasko BL, Caudy M, Martinez AG, Maass S et al (2018) Do demographic factors moderate how well criminal thinking predicts recidivism? Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 62(7):2045–2062

Freilich JD, Chermak SM, Gruenewald J (2015) The future of terrorism research: a review essay. Int J Comp Appl Crim Justice 39(4):353–369

Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, Shamliyan T, Sedrakyan A, Wilt TJ et al (2011) Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol 64(11):1187–1197

Genckaya Ö, Togan S, Schulz L, Karadag R (2018) Sustainable governance indicators: 2018 Turkey report. Bertelsmann Schiftung, Güterslohp

Gill P (2015) Toward a scientific approach to identifying and understanding indicators of radicalization and terrorist intent: eight key problems. J Threat Assess Manag 2(3–4):187–191

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Gøtzsche-Astrup O (2018) The time for causal designs: review and evaluation of empirical support for mechanisms of political radicalisation. Aggress Violent Beh 39:90–99

Hafez M, Mullins C (2015) The radicalization puzzle: a theoretical synthesis of empirical approaches to homegrown extremism. Stud Confl Terror 38(11):958–975

Haggerty KD, Bucerius SM (2018) Radicalization as martialization: towards a better appreciation for the progression to violence. Terror Polit Violence. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2017.1404455

Hammerstrøm K, Wade A, Hanz K, Jørgensen A (2009) Searching for studies: information retrieval methods group policy brief. The Campbell Collaboration, Oslo

Hanushek EJ, Jackson E (1977) Statistical methods for social scientists. Academic Press, New York

*Harms J (2017) The war on terror and accomplices: an exploratory study of individuals who provide material support to terrorists. Secur J 30(2):417–436

Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl TI, Farrington DP, Brewer D, Catalano RF, Harachi TW et al (2000) Predictors of youth violence. Retrieved from Washington, DC

Hedges L, Olkin I (1985) Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press, Orlando

Higgins J, Green S (2005) Highly sensitive search strategies for identifying reports of randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 4.2. 5 [updated May 2005]; Appendix 5b. The Cochrane Library, 3

Higginson A, Benier K, Shenderovich Y, Bedford L, Mazerolle L, Murray J (2014) Protocol: predictors of youth gang membership in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Campbell Collab Libr Syst Rev 10:1–60

Hirschi T (1969) Causes of delinquency. University of California Press, Berkeley

Hockenhull JC, Cherry MG, Whittington R, Dickson, RC, Leitner M, Barr W, McGuire J (2015) Heterogeneity in interpersonal violence outcome research: an investigation and discussion of clinical and research implications. Agress Violent Behav 22:18–25

Holt TJ, Freilich JD, Chermak SM, LaFree G (2018) Examining the utility of social control and social learning in the radicalization of violent and non-violent extremists. Dyn Asymmetric Conf 11(3):125–148

Horgan J (2008) From profiles to and roots to: perspectives from psychology on radicalization into terrorism. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 618(1):80–94

Hubbard DJ, Pratt TC (2002) A meta-analysis of the predictors of delinquency among girls. J Offender Rehabil 34(3):1–13

Hunter JE, Schmidt FL (2004) Methods of meta-analysis: correcting error and bias in research findings. Sage, Thousand Oaks

ICPC (2015) Preventing radicalization: a systematic review. International Centre for the Prevention of Crime, Montreal

Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS (2004) Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull 130(1):19

*Jasko K, LaFree G, Kruglanski A (2017) Quest for significance and violent extremism: the case of domestic radicalization. Polit Psychol 38(5):815–831

*Kalmoe NP (2014) Fueling the fire: violent metaphors, trait aggression, and support for political violence. Polit Commun 31(4):545–563

Kazdin AE, Kraemer HC, Kessler RC, Kupfer DJ, Offord DR (1997) Contributions of risk-factor research to developmental psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 17(4):375–406

Klausen J, Campion S, Needle N, Nguyen G, Libretti R (2016) Toward a behavioral model of “homegrown” radicalization trajectories. Stud Confl Terror 39(1):67–83

Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ (1997) Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(4):337–343

Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D (2001) How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry 158(6):848–856

*Krueger AB (2008) What makes a homegrown terrorist? Human capital and participation in domestic Islamic terrorist groups in the USA. Econ Lett 101(3):293–296

*LaFree G, Jensen MA, James PA, Safer-Lichtenstein A (2018) Correlates of violent political extremism in the United States. Criminology 56(2):233–268

Laqueur W (1999) The new terrorism: fanaticism and the arms of mass destruction. Oxford University Press, New York

Laycock G (2012) In support of evidence-based approaches: a response to Lum and Kennedy. Polic J Policy Pract 6(4):324–326

Liem M, van Buuren J, de Roy van Zuijdewijn J, Schönberger H, Bakker E (2018) European lone actor terrorists versus “common” homicide offenders: an empirical analysis. Homicide Stud 22(1):45–69

Lilly JR, Cullen FT, Ball RA (1995) Criminological theory: context and consequences, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Lipsey MW (2003) Those Confounded Moderators in Meta-Analysis: good, bad, and ugly. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 587(1):69–81

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB (2001) Practical meta-analysis. Sage Publications, Inc

*Littler M (2017) Rethinking democracy and terrorism: a quantitative analysis of attitudes to democratic politics and support for terrorism in the UK. Behav Sci Terror Polit Aggress 9(1):52–61

Lloyd M, Dean C (2015) The development of structured guidelines for assessing risk in extremist offenders. J Threat Assess Manag 2(1):40

Lösel F (2018) Evidence comes by replication, but needs differentiation: the reproducibility issue in science and its relevance for criminology. J f Exp Criminol 14(3):257–278

Lösel F, Farrington DP (2012) Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. Am J Prev Med 43(2):S8–S23

Lösel F, King S, Bender D, Jugl I (2018) Protective factors against extremism and violent radicalization: a systematic review of research. Int J Dev Sci 12(1–2):89–102

Lyons HA, Harbinson HJ (1986) A comparison of political and non-political murderers in Northern Ireland, 1974–84. Med Sci Law 26(3):193–198

*Macdougall AI, van der Veen J, Feddes AR, Nickolson L, Doosje B (2018) Different strokes for different folks: the role of psychological needs and other risk factors in early radicalisation. Int J Dev Sci. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-170232

Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM (2018) A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook use. Comput Hum Behav 83:262–277

May AM, Klonsky ED (2016) What distinguishes suicide attempters from suicide ideators? A meta-analysis of potential factors. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 23(1):5–20

McCauley C, Moskalenko S (2008) Mechanisms of political radicalization: pathways toward terrorism. Terror Polit Violence 20(3):415–433

McCauley C, Moskalenko S (2017) Understanding political radicalization: the two-pyramids model. Am Psychol 72(3):205

*McCauley C (2012) Testing theories of radicalization in polls of US Muslims. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy 12(1):296–311

McGilloway A, Ghosh P, Bhui K (2015) A systematic review of pathways to and processes associated with radicalization and extremism amongst Muslims in Western societies. Int Rev Psychiatry 27(1):39–50

Misiak B, Samochowiec J, Bhui K, Schouler-Ocak M, Demunter H, Kuey L et al (2019) A systematic review on the relationship between mental health, radicalization and mass violence. Eur Psychiatry 56:51–59

Monahan J (2012) The individual risk assessment of terrorism. Psychol Public Policy Law 18(2):167

Monahan J (2017) The individual risk assessment of terrorism: recent developments. In: LaFree G, Freilich JD (eds) The handbook of the criminology of terrorism. Wiley, Chichester, pp 520–534

*Moskalenko S, McCauley C (2009) Measuring political mobilization: the distinction between activism and radicalism. Terror Polit Violence 21(2):239–260

*Moyano M (2011) Factores psicosociales contribuyentes a la radicalización islamista de jóvenes en España. Construcción de un instrumento de evaluación (Tesis doctoral). Universidad de Granada

Mullins S (2009) Parallels between crime and terrorism: a social psychological perspective. Stud Confl Terror 32(9):811–830

Murray J, Farrington DP, Eisner MP (2009) Drawing conclusions about causes from systematic reviews of risk factors: the Cambridge Quality Checklists. J Exp Criminol 5(1):1–23

Murray J, Shenderovich Y, Gardner F, Mikton C, Derzon JH, Liu J, Eisner M (2018) Risk factors for antisocial behavior in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Crime Justice 47(1):255–364

Najaka SS, Gottfredson DC, Wilson DB (2001) A meta-analytic inquiry into the relationship between selected risk factors and problem behavior. Prev Sci 2(4):257–271

*Narraina M (2013) Who justifies terrorism? Masters thesis, Tilburg University

Neumann PR (2013) The trouble with radicalization. Int Aff 89(4):873–893

Neumann P, Kleinmann S (2013) How rigorous is radicalization research? Democr Secur 9(4):360–382

*Nivette A, Eisner M, Ribeaud D (2017) Developmental predictors of violent extremist attitudes: a test of general strain theory. J Res Crime Delinq 54(6):755–790

*Obaidi M, Bergh R, Sidanius J, Thomsen L (2018a) The mistreatment of my people: victimization by proxy and behavioral intentions to commit violence among Muslims in denmark. Polit Psychol 39(3):577–593

*Obaidi M, Kunst JR, Kteily N, Thomsen L, Sidanius J (2018b) Living under threat: mutual threat perception drives anti-Muslim and anti-Western hostility in the age of terrorism. Eur J Soc Psychol 48(5):567–584

*Oskooii KA, Dana K (2018) Muslims in Great Britain: the impact of mosque attendance on political behaviour and civic engagement. J Ethn Migr Stud 44(9):1479–1505

Pauwels LJ, Svensson R (2017) How robust is the moderating effect of extremist beliefs on the relationship between self-control and violent extremism? Crime Delinq 63(8):1000–1016

Pauwels LJ, Ljujic V, De Buck A (2018) Individual differences in political aggression: the role of social integration, perceived grievances and low self-control. Eur J Criminol. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818819216

*Pauwels L, Boudry M (2017) Over religie, geweld en extremistische morele overtuigingen: wat is de rol van religieus autoritarisme en gepercipieerde onrechtvaardigheid? Handb Politiediensten 122:163–196

*Pauwels L, De Waele M (2014) Youth involvement in politically motivated violence: why do social integration, perceived legitimacy, and perceived discrimination matter? Int J Conf Violence 8(1):134

*Pauwels LJ, Heylen B (2017) Perceived group threat, perceived injustice, and self-reported right-wing violence: an integrative approach to the explanation right-wing violence. J Interpers Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517713711

*Pauwels L, Schils N (2016) Differential online exposure to extremist content and political violence: testing the relative strength of social learning and competing perspectives. Terror Polit Violence 28(1):1–29

*Pedersen W, Vestel V, Bakken A (2017) At risk for radicalization and jihadism? A population-based study of Norwegian adolescents. Coop Confl 53(1):61–83

*Perliger A, Koehler-Derrick G, Pedahzur A (2016) The gap between participation and violence: why we need to disaggregate terrorist ‘profiles’. Int Stud Quart 60(2):220–229

Perry G, Wikström P-OH, Roman GD (2018) Differentiating right-wing extremism from potential for violent extremism: the role of criminogenic exposure. Int J Dev Sci. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-170240

Piazza JA (2006) Rooted in poverty? Terrorism, poor economic development, and social cleavages. Terror Polit Violence 18(1):159–177

Pinquart M (2017) Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: an updated meta-analysis. Dev Psychol 53(5):873

Pisoiu D (2012) Islamist radicalisation in Europe. An occupational change process. Routledge, New York

Pisoiu D, Ahmed R (2016) Radicalisation research—Gap analysis (RAN research paper). Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN), Amsterdam

Polanin J, Snilstveit B (2016) Converting between effect sizes. The Campbell Collaboration, Oslo

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2000) The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: a meta-analysis. Criminology 38(3):931–964

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2005) Assessing macro-level predictors and theories of crime: a meta-analysis. Crime Justice 32:373–450

Pratt TC, Cullen FT, Sellers CS, Thomas Winfree L Jr, Madensen TD, Daigle LE et al (2010) The empirical status of social learning theory: a meta-analysis. Justice Q 27(6):765–802

Pratt TC, Turanovic JJ, Fox KA, Wright KA (2014) Self-control and victimization: a meta-analysis. Criminology 52(1):87–116

Pyrooz DC, Turanovic JJ, Decker SH, Wu J (2016) Taking stock of the relationship between gang membership and offending: a meta-analysis. Crim Justice Behav 43(3):365–397

Rahimi S, Graumans R (2015) Reconsidering the relationship between integration and radicalization. J Deradicalization 5:28–62

Ribeiro J, Franklin J, Fox KR, Bentley K, Kleiman EM, Chang B, Nock MK (2016) Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med 46(2):225–236

*Rip B, Vallerand RJ, Lafrenière MAK (2012) Passion for a cause, passion for a creed: on ideological passion, identity threat, and extremism. J Pers 80(3):573–602

Rodríguez-Barranco M, Tobías A, Redondo D, Molina-Portillo E, Sánchez MJ (2017) Standardizing effect size from linear regression models with log-transformed variables for meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 17(44):1–9

Rosenthal R (1979) The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 86(3):638–641

Rosenthal R (1984) Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research

*Rousseau C, Hassan G, Mekki-Berrada A, El-Hage H, Lecompte V, Oulhote Y, Rousseau-Rizzi A (2016) Le défi du vivre ensemble: les déterminants individuels et sociaux du soutien à la radicalisation violente des collégiens et collégiennes au Québec (rapport de recherché). SHERPA, Institut universitaire au regard des communautés culturelles du CIUSSS Centre-Ouest-de-l’Île-de-Montréal, Montréal

Rutter M (2005) Environmentally mediated risks for psychopathology: research strategies and findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44(1):3–18

Sageman M (2014) The stagnation in terrorism research. Terror Political Violence 26(4):565–580

Schils N, Pauwels LJ (2016) Political violence and the mediating role of violent extremist propensities. J Strateg Secur 9(2):70–91

Serghiou S, Patel CJ, Tan YY, Koay P, Ioannidis JP (2016) Field-wide meta-analyses of observational associations can map selective availability of risk factors and the impact of model specifications. J Clin Epidemiol 71:58–67

Shenderovich Y, Eisner M, Mikton C, Gardner F, Liu J, Murray J (2016) Methods for conducting systematic reviews of risk factors in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Med Res Methodol 16(32):1–8

*Simon B, Reichert F, Grabow O (2013) When dual identity becomes a liability: identity and political radicalism among migrants. Psychol Sci 24(3):251–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612450889

Slootman M, Tillie J (2006) Processes of radicalisation: why some Amsterdam Muslims become radicals. Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam, pp 1–129

Smith AG (2018) Risk factors and indicators associated with radicalization to terrorism in the United States: what research sponsored by the National Institute of justice tells us. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

Smith BL, Morgan KD (1994) Terrorists right and left: empirical issues in profiling American terrorists. Stud Confl Terror 17(1):39–57

Staring RR (2014) Risks of radicalization among Turkish-Dutch young adults? CIROC Nieuwsbr 1(August 2014):5–6

Stern J (2016) Radicalization to extremism and mobilization to violence: what have we learned and what can we do about it? Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 668(1):102–117

*Szlachter D, Kaczorowski W, Muszynski Z, Potejko P, Chomentowski P, Borzol T (2012) Radicalization of religious minority groups and the terrorist threat-report from research on religious extremism among islam believers living in Poland. Intern Secur 4(2):79

*Tausch N, Spears R, Christ O (2009) Religious and national identity as predictors of attitudes towards the 7/7 bombings among British Muslims: an analysis of UK opinion poll data. Rev Int Psychol Soc 22(3–4):103–126

*Tausch N, Becker JC, Spears R, Christ O, Saab R, Singh P, Siddiqui RN (2011) Explaining radical group behavior: developing emotion and efficacy routes to normative and nonnormative collective action. J Pers Soc Psychol 101(1):129

Tol G, Akbaba Y (2016) Islamism in Western Europe: Milli Görüş in Germany. Interdiscip J Res Relig 12(6):1–16

*Trujillo HM, Prados M, Moyano M (2016) Psychometric properties of the spanish version of the activism and radicalism intention scale/propiedades psicométricas de la versión española de la escala de intención de activismo y radicalismo. Rev Psicol Soc 31(1):157–189

Tuck M, Riley D (1986) The theory of reasoned action: a decision theory of crime. In: Cornish DB, Clarke RV (eds) The reasoning criminal: rational choice perspectives on offending. Springer, Berlin, pp 156–169

*van Bergen DD, Feddes AF, Doosje B, Pels TVM (2015) Collective identity factors and the attitude toward violence in defense of ethnicity or religion among Muslim youth of Turkish and Moroccan Descent. Int J Intercult Relat 47:89–100

*van Bergen DD, Ersanilli EF, Pels TVM, De Ruyter DJ (2016) Turkish-Dutch youths’ attitude toward violence for defending the in-group: what role does perceived parenting play? Peace Confl J Peace Psychol 22(2):120–133

*Van den Bos K, Loseman A, Doosje B (2009) Waarom jongeren radicaliseren en sympathie krijgen voor terrorisme: Onrechtvaardigheid, onzekerheid en bedreigde groepen. Research and Documentation Centre of the Dutch Ministry of Justice, Utrecht

Van den Noortgate W, López-López JA, Marín-Martínez F, Sánchez-Meca J (2015) Meta-analysis of multiple outcomes: a multilevel approach. Behav Res Methods 47(4):1274–1294

*van der Veen J (2016) Predicting susceptibility to radicalization: an empirical exploration of psychological needs and perceptions of deprivation, injustice, and group threat, Report of Research Internship, 1–54

Vergani M, Iqbal M, Ilbahar E, Barton G (2018) The three Ps of radicalization: push, pull and personal. A systematic scoping review of the scientific evidence about radicalization into violent extremism. Stud Confl Terror. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1505686

Verwimp P (2016) Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq and the socio-economic environment they faced at home: a comparison of European countries. Perspect Terror 10(6):68–81

Victoroff J (2005) The mind of the terrorist: a review and critique of psychological approaches. J Conflict Resolut 49(1):3–42

Victoroff J, Adelman J (2012) Why do individuals resort to political violence? Approaches to the psychology of terrorism. In Breen-Smyth M (ed) The Ashgate research companion to political violence, Routledge, Milton Park, pp 137–168

*Victoroff J, Adelman JR, Matthews M (2012) Psychological factors associated with support for suicide bombing in the Muslim diaspora. Polit Psychol 33(6):791–809

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MWL (2010) Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 1(2):112–125

Walters GD, Bolger PC (2019) Procedural justice perceptions, legitimacy beliefs, and compliance with the law: a meta-analysis. J Exp Criminol 15(3):341–372

*Weerman FL, Ljujic V, Thijs F, Versteegt I, El Bouk F (2018) Socio-economic background of terrorism suspects in Europe (T2.7). Project PROTON. Retrieved on 1 May 1 2019 from https://www.projectproton.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/D2.1-Report-on-fact-related-to-terrorism.pdf

Weisburd D, Piquero AR (2008) How well do criminologists explain crime? Statistical modeling in published studies. Crime Justice 37(1):453–502

Wikström POH, Bouhana N (2017) Analyzing radicalization and terrorism: a situational action theory. In: LaFree G, Freilich JD (eds) The handbook of the criminology of terrorism. Wiley, Chichester, pp 175–186

Wilkinson P (2003) Why modern terrorism? Differentiating types and distinguishing ideological motivations. In: Kegley C (ed) The new global terrorism: causes and consequences. Prentice Hall, New Jersey, pp 106–138

*Wojcieszak M (2010) ‘Don’t talk to me’: effects of ideologically homogeneous online groups and politically dissimilar offline ties on extremism. New Media Soc 12(4):637–655

Wong TM, Slotboom A-M, Bijleveld CC (2010) Risk factors for delinquency in adolescent and young adult females: a European review. Eur J Criminol 7(4):266–284

Xue C, Ge Y, Tang B, Liu Y, Kang P, Wang M, Zhang L (2015) A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related PTSD among military personnel and veterans. PloS one 10(3):e0120270

Yoneoka D, Henmi M (2017) Meta-analytical synthesis of regression coefficients under different categorization scheme of continuous covariates. Stat Med 36(27):4336–4352

*Zaidise E, Canetti-Nisim D, Pedahzur A (2007) Politics of god or politics of man? The role of religion and deprivation in predicting support for political violence in israel. Polit Stud 55(3):499–521

*Zhirkov K, Verkuyten M, Weesie J (2014) Perceptions of world politics and support for terrorism among Muslims: evidence from Muslim countries and Western Europe. Confl Manag Peace Sci 31(5):481–501

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 699824. We would like to thank David B. Wilson, Hannah Rothstein, Michael Borenstein, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and advice in preparing the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wolfowicz, M., Litmanovitz, Y., Weisburd, D. et al. A Field-Wide Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Putative Risk and Protective Factors for Radicalization Outcomes. J Quant Criminol 36, 407–447 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09439-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09439-4