Abstract

Objective: To understand and describe the meaning of medications for patients. Methods: A metasynthesis of three different, yet complementary qualitative research studies, was conducted by two researchers. The first study was a phenomenological study of patients’ medication experiences that used unstructured interviews. The second study was an ethnographic study of pharmaceutical care practice, which included participant observation, in-depth interviews and focus groups with patients of pharmaceutical care. The third was a phenomenological study of the chronic illness experience of medically uninsured individuals in the United States and included an explicit aim to understand the medication experience within that context. The two researchers who conducted these three qualitative studies that examined the medication experience performed the meta-synthesis. The process began with the researchers reviewing the themes of the medication experience for each study. The researchers then aggregated the themes to identify the overlapping and similar themes of the medication experience and which themes are sub-themes within another theme versus a unique theme of the medication experience. The researchers then used the analytic technique, “free imaginative variation” to determine the essential, structural themes of the medication experience. Results: The meaning of medications for patients was captured as four themes of the medication experience: a meaningful encounter; bodily effects; unremitting nature; and exerting control. The medication experience is an individual’s subjective experience of taking a medication in his daily life. It begins as an encounter with a medication. It is an encounter that is given meaning before it occurs. The experience may include positive or negative bodily effects. The unremitting nature of a chronic medication often causes an individual to question the need for the medication. Subsequently, the individual may exert control by altering the way he takes the medication and often in part because of the gained expertise with the medication in his own body. Conclusion: The medication experience is a practice concept that serves to understand patients’ experiences and to understand an individual patient’s medication experience and medication-taking behaviors in order to meet his or her medication-related needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medications are one of the main options in the cure, treatment, and prevention of numerous medical conditions. However, there is still a gap in society regarding who must be held accountable for the outcomes of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacists have recently recognized the societal need to take responsibility for drug therapy outcomes [1]. However, if a health care practitioner strives to meet a patient’s drug-related needs then that practitioner must understand the meaning of medications for that patient [1–3]. However, the medication experience as a practice concept has not been comprehensively researched in pharmacy.

Medical and social scientists have examined the subjective experience of medications for patients, typically within the illness experience. Studies have been conducted on the meaning of medications for patients with specific medical conditions including: asthma [4]; hypertension [5]; and schizophrenia [6]. Moreover, studies have explored the meaning of therapeutic classes including: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [7]; hormone-replacement therapy [8, 9]; and antipsychotic medications [10]. Studies have also focused on patients’ medication practices or medication-taking behaviors [10, 11]; decision-making [8]; and cultural ideas of drug use [12]. Conrad [13] introduced the concept of medication practices or how patients manage their medications. He found that patients with epilepsy interpret the prescribed regimen and create medication practices that may vary from the prescribed one. Though many studies have examined the meaning of medications, most have focused on specific diseases or classes of drugs. The authors surmise that there could be a common experience of taking medications chronically that transcends the specificity of diseases and medications. Additionally, most studies on the meaning of medications have focused on patients’ decision-making, medication-taking behaviors, or compliance. Synthesizing the findings from three studies that investigate the meaning of taking medications for patients with many chronic conditions could provide a deeper level of understanding about a concept of importance to pharmacy practitioners. These three studies focused on understanding how patients experience taking medications on a daily basis; meaning how they feel, react and think about medications. This understanding may help pharmacists to better comprehend how and why patients make the decisions and take the actions they do. It is the goal of this article to present an understanding of the meaning of medications for patients, introduced here as the medication experience.

Methods

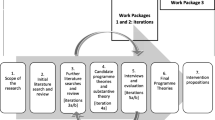

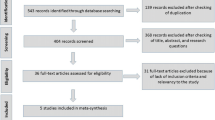

This paper is the result of a meta-synthesis of three different yet complementary qualitative studies that included aims to understand the medication experience. These three studies were conducted by the two authors. Table 1 describes each study’s method and participants’ demographics.

The first study was a phenomenological study of individuals’ experiences taking at least two prescription medications. The methods were guided by Van Manen’s [14] insights using in-depth interviews, which were audio-taped and transcribed. The analysis involved reading and coding each interview transcript for the meaning units of each participant’s experience. Meaning units are phrases or text sections that illustrate a segment of the meaning distinct from the adjacent text. Then the codes were reviewed to identify the common themes of the medication experience for all participants.

The second study was an ethnography that used a triangulation of methods to reach a comprehensive understanding of pharmaceutical care practice [3]. The study revealed patients’ medication experiences as a significant part of patients’ experiences with pharmaceutical care. The study was conducted over a period of eight months in six clinics and one community pharmacy. The sampling was theoretical sampling, which involved selecting participants who would yield information that was relevant to the understanding of experiences of those in the pharmaceutical care practices. The data analysis was conducted following the techniques of Wolcott [15].

The third study was an interpretive phenomenological study that used in-depth interviews to understand medically uninsured individuals’ (in the United States) chronic illness experiences, including the medication experience [16]. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. The interview transcripts and field notes were segmented and labeled for one of the three experiential units - the illness, medication, and uninsured experience. A thematic analysis of the lived experience of each segment of text was conducted coding each segment with a descriptive code that captured the meaning conveyed. The codes were iteratively refined, and removed as appropriate. This was in part conducted using an analytic method called free imaginative variation. Free imaginative variation involves removing a theme, then asking if the essence of the phenomenon withstands [14]. The resultant essential codes became the themes of the illness and medication experience of medically uninsured individuals.

The researchers used meta-synthesis of the three studies to reach a greater breadth of understanding about individuals’ medication experiences. Meta-synthesis is an analytic method that facilitates a fuller understanding of a phenomenon by providing an interpretive integration of qualitative findings. The meta-synthesis of qualitative findings is increasingly seen as essential to enhance the generalizability of qualitative research [17]. The two researchers who conducted these three qualitative studies performed the meta-synthesis. The process began with the researchers reviewing the themes of the medication experience for each study. The researchers then aggregated the themes to identify the overlapping and similar themes of the medication experience. The researchers used free imaginative variation to determine the essential themes of the medication experience and from these the prevailing themes were identified. The findings from the meta-synthesis of the three studies informed the meaning of medications (i.e., the medication experience) that is presented in this paper.

Results

The meaning of medications for participants was revealed as the following themes: a meaningful encounter, bodily effects, unremitting nature, and exerting control.

A meaningful encounter

The medication experience is first revealed as an encounter with a medication. It is an encounter that is embedded with meaning long before it occurs. The meaningful encounter can be revealed as a sense of losing control, a sign of getting older, cause questioning, and a meeting with stigma. Each of these sub-themes of the meaningful encounter is described below.

The encounter with a chronic medication for the first time can be experienced as a sense of losing control, as one participant states:

I used to think I was immune to disease. This body is so tremendous that it will never let me down, but here I was—I had to start taking medication.

One participant explicitly characterized her medical need for chronic medications as a loss of control:

I lost control of my health. I wish I could handle it myself.

Another participant describes a similar desire to treat her condition without medication:

I felt like if I took lorazepam that I’m failing. If I could fight it myself, get over it myself without the drug then I’m getting better.

Participants commonly ascribed a negative meaning to medications when they first encountered them or when they began taking an increasing number of medications chronically. Another study found loss of control as part of the meaning of medications for patients [18].

Many participants described medications as signifying aging. One participant characterized starting a medication as depressing because it indicated he was “getting older.” However, for a participant in her mid-twenties using several medications, the significance was even greater:

I feel like a 90-year-old woman. Like my grandpa, he’s on all these pills. If you’re an old person that’s okay, but if you’re young it’s really odd.

Medications distinguish the healthy from the sick and the young from the old. Taking chronic medications often made participants feel that they were now part of that group of people who take medications because they are getting older.

As part of the initial encounter with a chronic medication, many participants question the actual need for the medication they are prescribed.

I’m not sure what I’ll get from these medications.

Uncertainty arises when participants realize they are supposed to take a medication chronically.

I thought about what would happen to me if I just decided not to take it.

Questioning the need for a medication when it is first prescribed can be interpreted as resistance by health care professionals, whereas for participants it is a way to reclaim a degree of control. Participants sensed that their individual autonomy was undermined when taking chronic medications until the point they questioned the taken-for-granted notion that medications are the right option.

The first reactions to initiating a medication can also be shaped by the social views of the medical condition. For example, the reaction of individuals to initiating psychotropic medications can be a response to the stigma of mental illness. As expressed by participants in these studies, taking an antidepressant carries the shame associated with mental illness.

Maybe I’m just embarrassed, even if nobody would know. I think people would see me as weak.

When initiating a chronic medication, participants encountered different meanings that shaped their initial experience of the medication. Participants experienced the meaningful encounter with a chronic medication as a sense of losing control, a sign of getting older, causing them to question, and a meeting with stigma.

Bodily effects

Medications have expected pharmacological benefits as well as anticipated side effects and unanticipated adverse events, all of which are bodily experiences. When a patient’s experience of their body in illness is debilitating, a medication can provide relief and allow the patient to regain their “healthy” body. However, medications also can cause negative bodily sequelae that are part of a patient’s medication experience. The bodily effects of medications theme was revealed as the experience of a magic elixir and trade-offs.

The medication can “normalize” the patient or bring her body as a whole together:

At first I was very grateful that insulin existed—it saved my life. I am grateful that I’m alive. It is scary that you’re reliant on this magic elixir to be alive.

Participants who characterized their medications as “magic elixirs” often had medical conditions that incapacitated them.

I’ve struggled with depression all my life. My psychiatrist started me on antidepressants. I’m very grateful for these drugs. I wouldn’t be able to work if it wasn’t for them.

Sometimes the body, disrupted by a disease, can be brought back into balance with medications. Conrad [13] found that epileptic patients perceived taking their anticonvulsants as a ‘ticket’ to normality.

An important component of the bodily effects stemmed from what the medications did to improve their lives. In contrast, other participants experienced the negative sequelae of a medication. However, if the benefit experienced was sufficiently good they would be willing to accept the side effects as a trade-off. One participant indicates:

You learn to decide if you’re gonna take the side effect over how well it helps with your depression. Citalopram worked so well for me that I didn’t care that I was peeing my pants.

Another participant describes:

I’m not worried about taking them, mostly because if they’re going to kill me earlier I don’t care because I just want the problem to go away.

Another study identified that patients are aware of the trade-offs that must be made while trying to maximize their well-being [10]. Participants also expressed concern about taking a medication until they experienced the benefits.

Even though I was hesitant at the beginning, after seeing the benefits and realizing how life can be with “just a medication” and feel good…

This theme illustrates how patients may rationally approach the decision to take or continue a medication and that they are willing to take a medication once they believe that the medication’s benefits outweigh its risks.

Unremitting nature

The unremitting nature of a chronic medication, like a chronic condition, is a burden.

The first time somebody told me I would have to take that for the rest of my life I got mad.

Another participant states:

I feel that part of my life now is going to be me taking more and more medicine and relying on medications to continue living.

The expectation of taking a medication regularly positions the patient as a passive agent, and the medication then becomes a symbol of dependence.

I think, what if I went a couple months without taking anything? But I don’t feel I have that choice. Those pills keep you prisoner. If you go on a trip, that’s one of the major factors - it’s more important than packing enough underclothes.

This participant has lost autonomy and in her words she is held captive by her medications. Additionally, due to the chronicity of medications participants have to take responsibility.

It’s this constant thing you wish you could have a break from, but you can’t.

In order to achieve normal function some participants have to take medications indefinitely, yet they still wish that wasn’t the case.

You feel sorry for yourself because you’re still on these pills. I don’t want to think - it’s been this long and I’m still on them.

Exerting control

The last theme of the medication experience was revealed as participants exerting control over their medications. After encountering the meaning of a medication, questioning it, realizing the bodily effects and the continuous nature of medications, participants experimented with becoming the managers of their treatment regimens. After taking chronic medications for a period of time participants became familiar with the effects of medications on their bodies. They discovered creative ways to manage their medications and exert control over them; in part because they were now knowledgeable.

I don’t think people understand how much you have to think about it. I call it thinking like a pancreas. You have to do all the work. You have to determine how much you take [insulin] and that changes from day to day and from hour to hour...

Participants have their own method of learning pharmacology–through experience. They know their bodies and perceive the changes produced by medications. As a result, exerting control is a common practice in individuals taking medications chronically.

I know how to go off of it, decrease it very slowly or you get sick.

Health care professionals rarely acknowledge this practice as a form of exerting control; instead it is labeled as noncompliance. Another participant offers a description of being attuned to her body and taking control:

As the doctor upped the dose I felt like I was high … I started getting a really weird feeling in my head, I even had pains in my chest. I thought to myself, I’m just gonna quit taking this. So I quit, and then as the week went on I was slowly getting better.

Participants also self manage their medications by reducing the dose particularly when they are uncertain about the effects or concerned about becoming “dependent.”

I like being able to adjust my sertraline as I find necessary. I like to have that control.

As the participants in these studies convey and Carrick et al. [10] also observed, patients are the ultimate managers of their treatments and create their own medication practices. From the patient’s perspective, such behaviors are rational and help them preserve control. Ramalho de Oliveira and Shoemaker [2] argued that pharmacists typically take a paternalistic perspective, viewing patients’ non-compliant behavior as an irrational act. The understanding of patients exerting control over their medications provides a context in which to challenge the notion that patients’ medication practices are illogical.

Discussion

The authors define the medication experience as an individual’s subjective experience of taking a medication in his daily life. It begins as an encounter with a chronic medication. It is an encounter that is given meaning before it happens and is often a reaction to the symbol that medication holds. The experience may include positive or negative bodily effects. The unremitting nature of a chronic medication often causes an individual to question the need for the medication. Subsequently, the individual may exert control by altering the way he takes the medication and often in part because of the gained expertise with the medication in his own body.

In this paper, the themes of the medication experience are described as being essentially independent of one another; however there was a temporal location in which the meanings seemed to arise in the participants’ stories. It appeared that the four themes are essentially stages of the medication experience or the experience of taking a chronic medication has a natural progression from a meaningful encounter to participants exerting control. Other scholars have recognized a pattern or stages that patients go through with specific medications. A study of young women using selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for depression revealed that SSRI users passed through stages corresponding to how they felt about themselves [7]. Further research is needed to explore the validity of patients’ medication experiences as a progression through stages or a journey.

Since medications are among the most common options in the treatment and mitigation of diseases, it is essential for health care practitioners to acknowledge an individual’s medication experience in order to positively influence patients’ medication-taking behaviors. Patients’ decisions, which at first appear irrational, might be seen as intelligent when a practitioner understands a patient’s unique medication experience. Cipolle et al. [1] state “a practitioner cannot make sound clinical decisions without a good understanding of the patient’s medication experience” and urge practitioners to take responsibility for improving each patient’s medication experience. The findings of this study provide pharmacists insights on the meanings that medications can have for patients, which may explain and certainly impact their medication-taking behavior. For example, understanding the potential meaning of initiating a chronic medication (e.g., losing control) may help explain a patient’s reticence to taking the medication.

A limitation of this study is that the synthesis of findings was from studies that explored the medication experience across multiple chronic conditions, which makes it difficult to discern the aspects of participants’ experiences related to the unique illness experience of a specific disease. Additionally, the participants were all in the U.S. (though not all native born) and the medication experiences may vary in different cultures. Even though meta-synthesis addresses the issue of small sample sizes in qualitative research, this study still has a relatively small sample size (n = 41), which limits the applicability of these findings to others’ experiences. Lastly, the authors re-analyzed their own work, which could have led to bias and reinforcement of the original findings.

Conclusions

The medication experience is a practice concept that serves to understand patients’ experiences and to understand an individual patient’s medication experience in order to meet his or her medication-related needs. The understanding of the medication experience presented in this paper can serve as a guide for health care practitioners who are interested in meeting a patient’s medication-related needs and provide a foundation from which to interpret each individual’s unique medication experience. Additional research is needed to further understand the medication experience and examine how it can be used to optimize patients’ medication-taking behaviors as well as if there are stages of the medication experience that patients pass through.

References

Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice: The clinician’s guide. 2nd ed. New York:McGraw-Hill; 2004. ISBN 0-07-136259-2.

Ramalho de Oliveira D, Shoemaker SJ. Achieving patient centeredness in pharmacy practice: openness and the pharmacist’s natural attitude. J Am Pharm Assoc 2006;46(1):56–66.

Ramalho de Oliveira D. Pharmaceutical care uncovered: an ethnographic study of pharmaceutical care practice [dissertation]. Minneapolis (MN): University of Minnesota;2003.

Adams S, Pill R, Jones A. Medication, chronic illness and identity: The perspective of people with asthma. Soc Sci Med 1997;45(2):189–01.

Visawanathan H, Lambert BL. An inquiry into medication meanings, illness, medication use, and the transformative potential of chronic illness among African Americans with hypertension. Res Social Adm Pharm 2005;1:21–39.

Rogers A, Day JC, Williams B, Randall F, Wood P, Healy D, et al. The meaning and management of neuroleptic medication: A study of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Soc Sci Med 1998;47(9):1313–23.

Knudsen P, Holme Hansen E, Morgall Traulsen J, Eskildsen K. Changes in self-concept while using SSRI antidepressants. Qual Health Res 2002;12(7):932–44.

Hunter MS, O’Dea I, Britten N. Decision-making and hormone replacement therapy: a qualitative analysis. Soc Sci Med 1997;45(10):1541–48.

Stephens C, Budge RC, Carryer J. What is this thing called hormone replacement therapy? Discursive construction of medication in situated practice. Qual Health Res 2002;12(3):347–59.

Carrick R, Mitchell A, Powell R, Lloyd K. The quest for well-being: a qualitative study of the experience of taking antipsychotic medication. Psychol Psychother 2004;77:19–33.

Pound P, Britten N, Morgan M, Yardley L, Pope C, Daker-White G, et al. Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:133–55.

Lumme-Sandt K, Hervonen A, Jylha M. Interpretative repertoires of medication among the oldest-old. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1843–1850.

Conrad P. The meaning of medication: another look at compliance. Soc Sci Med 1985;20:29–37.

Van Manen M. Researching lived experience: human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. New York: State University of New York Press; 1990. ISBN 0791404269.

Wolcott HF. Ethnography: A way of seeing. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press; 1999. ISBN-10: 0761990909.

Shoemaker SJ. Listening in the shadows: the chronic illness experience of medically uninsured individuals [dissertation]. Minneapolis (MN): University of Minnesota; 2005.

Sandelowsky M, Barroso J. Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qual Health Res 2003;13(6):781–820.

Murawski MM, Bentley JP. Pharmaceutical therapy-related quality of life: conceptual development. J Soc Adm Pharm 2001;18(1):2–14.

Acknowledgements and funding

Dr. Shoemaker would like to acknowledge Wal Mart Inc. for their donation of the $25 gift cards provided as compensation to the participants in the illness experience of medically uninsured study and Dr. Ramalho de Oliveira would like to thank the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico–CNPq (Brazilian Funding Agency) for support of her dissertation research on pharmaceutical care practice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Shoemaker, S.J., Ramalho de Oliveira, D. Understanding the meaning of medications for patients: The medication experience. Pharm World Sci 30, 86–91 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-007-9148-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-007-9148-5