Abstract

For most immigrants and ethnic minority groups, everyday life in the country of settlement raises question of adaptation and belonging. Aside from factors such as lower income, lower education and poorer health, being an ethnic minority member carries additional factors that can lower general life satisfaction. Using data from two studies the present paper shows that ethnic minority group members (Turkish-Dutch) have lower general life satisfaction than a comparable majority group (Dutch) because they are less satisfied with their life in the country of settlement. In addition, Study 2 showed that higher perceived structural discrimination was associated with lower life satisfaction in the country of settlement, but also with higher ethnic group identification that, in turn, made a positive contribution to general life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Although the number of studies is quite limited, researchers have found relatively low life satisfaction among ethnic and racial minority groups. The effect is still found when relevant demographic and other factors are controlled for (e.g., Andrews and Withey 1976; Campbell et al. 1976; Michalos and Zumbo 2001; Ullman and Tatar 2001; Verkuyten 1986). For example, in a recent national survey in the Netherlands it was found that the general life satisfaction of immigrant and ethnic minority group members was substantially lower than that of the ethnic Dutch (Central Bureau of Statistics 2005). In an analysis controlling for income, educational level, physical health, age, and gender it turned out that compared to the Dutch majority group, twice as many minority group members felt not very happy (11% vs. 24%). Hence, it appears that, aside from factors such as lower income, lower education, and poorer health, being an ethnic minority group member carries additional factors that lower general life satisfaction.

Everyday life in the country of settlement is a central issue for immigrants and ethnic minority groups. Immigration and a different cultural background raises questions of psychological and sociocultural adaptation (Ward 1996) involving, for example, the acquisition of socially and culturally appropriate skills and practices needed to operate effectively in society. It also raises questions of belonging and acceptance. The majority group and the broader society can be accepting and inclusive in its orientation toward ethnic and cultural diversity or rather rejecting and exclusive. Acculturation research has shown that the perceived orientations of the majority group are important for understanding minorities’ life satisfaction and their attachment to their own ethnic group and the larger society (Berry 2001; Vedder et al. 2006). Minority members who feel unwelcome or discriminated against are likely to be less satisfied with their life in the country of settlement. They can also develop a stronger identification with their own ethnic group. Group identification implies a sense of belonging that might attenuate or buffer the negative effects of perceived discrimination on life satisfaction.

In two studies conducted in the Netherlands, this paper examines the life satisfaction of ethnic minority members in comparison to the majority group. It is argued that for immigrant and ethnic minority groups, satisfaction with one’s life in the country of settlement is an important aspect of general life satisfaction. Hence, it was expected that ethnic minority members have lower general life satisfaction because they are less satisfaction with their life in the country of settlement. In Study 2, perceived structural ethnic discrimination in Dutch society was examined as an important reason for being less satisfaction with living in the country. In addition, in Study 2 it was examined whether identification with the own ethnic minority group contributes positively to general life satisfaction.

1.1 Domains of Life Satisfaction

The domain-of-life literature suggests that general life satisfaction can be distinguished from satisfaction in different domains of life. How people feel about their life in general is something different than how they feel about different domains of life (Wu and Yao 2007). Although, a relationship between general life satisfaction and satisfaction in domains of life is assumed by most researchers there is less agreement on how this relationship should be understood. There is, for example, the distinction between bottom-up versus top-down approaches (Diener 1984). The former argues that general life satisfaction can be understood as the result of satisfaction in the domains of life (e.g., Argyle 1987; Cummins 1996), whereas the latter suggest that general life satisfaction induces a rosy outlook that affects domain satisfactions (e.g., Headley and Veenhoven 1989). Both approaches find empirical support and the direction of influence seems to vary with the domain studied (Headley et al. 1991; Lance et al. 1995), and the models and datasets used (Scherpenzeel and Saris 1996).

Most researchers, however, accept the idea that satisfaction in domains of life contributes to the explanation of general life satisfaction, whether in an additive or some other way (Rojas 2006; Wu and Yao 2006). Particularly domains that are very important for a certain group of people in a certain context can be expected to have a bottom-up effect on general life satisfaction. A distinction between domains of life is somewhat arbitrary and various domain partitions have been proposed (e.g. Argyle 1987; Cummins 1996). What is crucial, however, is that the domains of life distinguished relate to the way people think about their lives. For immigrants, everyday life in the country of settlement is a central issue.

In Canada (British Columbia) Michalos and Zumbo (2001) found that domain satisfaction scores are more important statistical predictors of happiness and life satisfaction than a variety of ethnic/cultural related phenomena including modern prejudice. However, this study was not concerned with immigrant groups, did not consider people’s satisfaction with their life in the country of settlement and did not focus on perceived discrimination and ethnic group identification.

In our two studies it was expected that ethnic minority members have lower general life satisfaction than the majority group because they are less satisfied with their lives in the country they live in. The second study, in addition, focused on perceived structural ethnic discrimination and the level of identification with the own ethnic minority group.

1.2 Perceived Discrimination and Group Identification

Experiences and perceptions of ethnic discrimination can be expected to have negative repercussions for the way minority members feel about their lives. In different countries, empirical evidence indicates a negative relationship between perceived ethnic discrimination and life satisfaction. In their research among more than 7000 immigrants in 13 countries, Vedder et al. (2006), for example, found that perceived discrimination was negatively related to psychological adaptation, including general life satisfaction.

However, these studies do not make a distinction between general life satisfaction and life satisfaction in the country of settlement. It is likely that perceived structural discrimination affects life satisfaction in the country of settlement rather than general life satisfaction directly. After-all, there are many possible domains that can contribute to general life satisfaction, such as family life, work and employment, religious belief, and leisure (Argyle 1987; Cummins 1996; Michalos and Zumbo 2001). Hence, in Study 2, I expected that life satisfaction in the Netherlands mediates the relationship between perceived structural discrimination and general life satisfaction. For example, an ethnic minority individual may have rather low general life satisfaction because she is not very satisfied with her life in the country of settlement, and she is not very satisfied with this life because she perceives structural discrimination of ethnic minority groups in society. The existence of such a mediating role for life satisfaction in the country of settlement would help us to understand how exactly, or the pathway by which, structural discrimination affects general life satisfaction.

Existing research suggest an additional pathway by which structural discrimination can affect general life satisfaction among ethnic minority groups. According to the rejection-identification model, discrimination presents a threat to group identity, making people increasingly turn toward the own minority group (Branscombe et al. 1999). The model, for which there is quite some empirical evidence (see Schmitt and Branscombe 2002), proposes that members of minority groups cope with the pain of discrimination by increasing identification with their group. Further, group identification would attenuate the negative effects of perceived discrimination on psychological well-being. Group identification implies a sense of belonging and this sense is implicated in the psychological well-being of ethnic minority group members (e.g., Zheng et al. 2004). Ethnic identification may play an important role in life satisfaction because people attribute value to their ethnic group and derive satisfaction from their belongingness and sense of inclusion. Empirically, various studies have found that ethnic identity is psychologically more salient and important to ethnic minorities than it is to their majority group contemporaries (see Verkuyten 2005). Hence, in Study 2 I also examined ethnic identification. For the ethnic minority participants and following the rejection-identification model I expected ethnic identification to mediate the relationship between perceived structural discrimination and general life satisfaction.

1.3 The National Context

The expectations were tested in two studies among Turkish-Dutch and ethnic Dutch participants. The Turkish-Dutch are the numerically largest minority group living in the Netherlands. They have a history of migrant labor and most of them are Muslim and have a strong sense of their own culture and identity that they want to preserve (Verkuyten 2005). Together with the Moroccan-Dutch, they are also at the bottom of the ethnic hierarchy (Hagendoorn 1995) showing that they are the least accepted in the Netherlands, and the level of acceptance has decreased in recent years (Verkuyten and Zaremba 2005).

In both studies the role of gender, age, length of residence in the Netherlands, and passport nationality were also considered. With longer residence, cultural and social skills, language proficiency and usage, and social contacts with majority group members tend to be higher (Phinney et al. 2006). This could mean that life satisfaction in the Netherlands, and thereby general life satisfaction, are also higher among those Turkish-Dutch participants that reside longer in the country. Within the Turkish-Dutch community, people have a Turkish passport, a Dutch passport or dual citizenship, all of which are legally possible in the Netherlands. Having a Dutch passport (with or without a Turkish one) can have more instrumental than symbolic meanings because it allows one, for example, to vote in national elections and to travel freely within the European Union. However, one’s passport identity might also be related to one’s orientation on the country of settlement. Therefore this factor was included in both studies.

2 Study 1

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Sample

In total, 141 respondents had a father and mother of Turkish background, and 132 respondents were ethnically Dutch. Of these participants 51.2% were women and 48.8% were men. The participants came from the cities of Rotterdam and Utrecht. They were between 17 and 39 years of age and their mean age was 22.6. The two ethnic groups were matched in terms of educational background and there were no gender or age differences between the two. Of the Turkish-Dutch participants, 21.7% had Turkish nationality, 37.9% had Dutch nationality, and 40.4% had dual citizenship. Further, the Turkish-Dutch participants were living between 6 and 39 years in the Netherlands with a mean of 20.5 years.

2.1.2 Measures

Life satisfaction in the Netherlands was measured first in the questionnaire and was assessed by four items adapted from Diener et al. (1985). The items were ‘I feel at home in the Netherlands’, ‘I am satisfied in the Netherlands’, ‘I feel that I fit in the Netherlands’, and ‘I feel happy living in the Netherlands’. Items were measured on scales ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly).

General life satisfaction was also assessed by four items taken from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985). Using seven-point scales, the items were, ‘The conditions in my life are excellent’, ‘I am satisfied with my life’, ‘If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing’, and ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’.

3 Results

3.1 Scale Analysis

It was expected that general life satisfaction was empirically distinguishable from life satisfaction related to living in the Netherlands. Maximum likelihood estimation with oblique rotation was conducted to examine the dimensionality of the two scales for the majority and minority group separately. In addition, a coefficient of factorial agreement between groups, Tucker’s phi was computed. A value higher than .90 is seen as evidence of factorial similarity allowing for group comparisons (Van de Vijver and Leung 1997).

For the Dutch majority group a two-factor structure emerged. The first factor explained 49.2% of the variance and the second factor explained 14.4%. The four items intended to measure life satisfaction in the Netherlands loaded highly on the first factor (>.76) and the highest load on the second factor was .23. On the second factor, three general life satisfaction items had a high load (>.66 and <.29 on the other factor). The fourth item loaded on both factors.

For the Turkish-Dutch minority group, two factors were also found and these accounted for 52.6% and 16.2% of the variance, respectively. The four items on life satisfaction in the Netherlands loaded high on the first factor (>.78) and had a load of <.23 on the second factor. Again, three items loaded on the second factor (>.75, and <.29 on the other factor) and the fourth item loaded on both factors. Hence, for seven items the factor analysis confirmed that a distinction can be made between life satisfaction in the Netherlands and general life satisfaction. This was found for both groups and Tucker’s phi was .93.

For life satisfaction in the Netherlands, Cronbach’s alpha was .87 for the majority group, and .91 for the ethnic minorities. For general life satisfaction, alpha was .76 for the former group and .72 for the latter one. Both scales were statistically significant and positively related (r = .37, p < .001) but the correlation indicates that they shared a limited amount of variance.

3.2 Life in the Netherlands

A regression analysis was conducted to predict life satisfaction in the Netherlands. The effects of gender, age and ethnic group were entered as factors. Gender and ethnic group were dummy-coded with respectively males and the Dutch as comparison group. The regression model was significant, F(3, 269) = 19.54, p < .001, explaining 18% of the variance. There were no significant gender and age differences, but there was a significant effect for ethnic group (β = −.42, t = 7.52, p < .001). The Turkish-Dutch respondents were significantly less satisfied with their lives in the Netherlands than the Dutch respondents (M = 4.65, SD = 1.49, and M = 5.79, SD = .94, respectively). However, also the Turkish-Dutch scored above the neutral mid-point of the scale indicating satisfaction with their lives in the Netherlands.

3.3 General Life Satisfaction

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to predict general life satisfaction. The effects of gender, age and ethnic group were entered on Step 1, and the measure for life satisfaction in the Netherlands was entered on Step 2. The first model explained 6.0% of the variance in general life satisfaction, F change(3, 269) = 5.69, p < .001. Gender was not a significant predictor but older respondents indicated lower general life satisfaction compared to younger respondents (β = −.16, t = 2.78, p < .01). In addition, Dutch respondents had higher general life satisfaction than the Turkish-Dutch (β = −.17, t = 2.89, p < .01; M = 5.32, SD = 1.80, and M = 4.78, SD = 1.17, respectively). Both groups score above the mid-point of the scale indicating that, in general, the participants were satisfied with their lives.

The addition of the measure of life satisfaction in the Netherlands on Step 2 significantly increased the explained variance, \( R^{2}_{{{\text{change}}}} \) = .10, F change(1, 268) = 32.61, p < .001. Higher life satisfaction in the Netherlands was significantly related to higher general life satisfaction (β = .35, t = 5.71, p < .001). Age remained a significant negative predictor (β = −.14, t = 2.45, p = .013), but the effect for ethnic group was no longer significant (β = −.03). Thus, there was no difference in general life satisfaction between the Dutch and Turkish-Dutch respondents when life satisfaction in the Netherlands was taken into account.

3.4 The Turkish-Dutch

To examine the responses of the Turkish-Dutch in more detail additional hierarchical regression analyses were conducted with length of residence and passport nationality as additional predictors. Passport nationality was dummy-coded into two variables such that the Turkish nationality was the referent group. A first analyses predicted life satisfaction in the Netherlands. The regression model explained 9.3% of the variance, F(5, 135) = 2.78, p = .021. There was only one significant independent predictor. The longer the respondents had been living in the Netherlands, the more satisfied they were about their life in this country (β = .30, t = 3.16, p = .002). The effects of gender, age and passport nationality were not significant.

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to predict general life satisfaction. The effects of gender, age, length of residence, and passport nationality were entered on Step 1, and the main effect of life satisfaction in the Netherlands was entered on Step 2. The model in the first step did not explain a significant part of the variance in general life satisfaction, F change(5, 135) = 1.11, p > .10. Thus, there were no effects for gender, age, length of residence, and nationality on general life satisfaction. The addition of the measure on Step 2 significantly increased the explained variance, R 2 = .19, F change(1, 134) = 33.57, p < .001. Satisfaction in the Netherlands was positively associated to general life satisfaction (β = .46, t = 5.79, p < .001).

3.5 Discussion

The results of the first study indicate that the Turkish-Dutch had lower general life satisfaction than the Dutch and were also less satisfied with their life in the Netherlands. However, the Turkish-Dutch and the Dutch did not differ in general life satisfaction in a regression analysis that took life satisfaction in the Netherlands into account. Thus, there was statistical evidence that ethnic minority members are less satisfied with their life in general because they are less satisfied with living in the Netherlands. Sociocultural adjustment is likely an important factor for immigrant and ethnic minority groups to feel at home and to be satisfied with their life in the country (Sam et al. 2006). The positive association between length of residence and life satisfaction in the Netherlands seems to supports this idea (see also Verkuyten and Nekuee 1999).

4 Study 2

An other possible reason for the Turkish-Dutch participants being relatively dissatisfied with their life in the Netherlands is that they live in a majority group dominated society. Having a lower social status and a higher change of having to deal with ethnic discrimination might affect their feelings of living in the Netherlands negatively. In the second study we examined this idea by focusing on perceived structural discrimination. In addition, people can cope with the pain of discrimination by turning to their own ethnic group from which they derive a sense of belongingness and inclusion which contributes to their satisfaction with life. In Study 2 and for the Turkish-Dutch participants, it was expected that structural discrimination has a negative impact on general life satisfaction via its influence on life satisfaction in the Netherlands. Furthermore, higher perceived structural discrimination was also expected to lead to a stronger identification with the own ethnic group, and group identification was expected to contribute to general life satisfaction.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Sample

In total, 208 respondents participated in this study. Of this sample, 105 had a father and mother of Turkish background, and 103 respondents were ethnically Dutch. Of the participants 59.5% were women and 40.5% were men. The participants came from the cities of Rotterdam and Utrecht. They were between 17 and 29 years of age and their mean age was 21.8. The two ethnic groups were, again, matched for educational background and there were no gender or age differences between the two. Of the Turkish-Dutch participants, 13.2% had Turkish nationality, 36.8% had Dutch nationality, and 50% had dual citizenship. Further, 79% of the Turkish-Dutch participants had been born in the Netherlands and for the others the mean number of years living in the Netherlands was 16.6.

4.1.2 Measures

In Study 2, life satisfaction in the Netherlands and general life satisfaction were each assessed by three of the four items used in Study 1.

Ethnic group-identification was assessed by asking the participants to respond to six items that were taken from previous studies in the Netherlands (see Verkuyten 2005). These items measure the importance attached to one’s ethnic background and are similar to the items on Luhtanen and Crocker’s (1992) identity and membership subscales. Items were measured on scales ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The six-item scale was internally consistent with a Cronbach’s alpha equal to .78 for the Dutch participants and .82 for the Turkish-Dutch participants.

In measuring perceived structural discrimination by the Turkish-Dutch participants, five items were used that were taken from Phalet, Van Lotringen and Entzinger (2000). The items assess the degree of structural discrimination of Turkish-Dutch people. The participants were asked whether they agreed with statements about discrimination toward Turkish-Dutch people by the police, the government, and on the labor and housing market. The participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement using a five-point scale ranging form ‘No, certainly not true’ (1) to ‘Yes, certainly true’ (5). For the Turkish-Dutch participants, Cronbach’s alpha was .74.

5 Results

5.1 Scale Analysis

Similar to Study 1, general life satisfaction was found to be empirically distinguishable from life satisfaction related to living in the Netherlands. Maximum likelihood estimation with oblique rotation yielded for the Dutch majority group a two-factor structure. The first factor explained 47.4% of the variance and the second factor explained 20.2%. The items intended to measure life satisfaction in the Netherlands loaded highly on the one factor (>.80) and the highest load on the other factor was .28. On the second factor, the three general life satisfaction items had a high load (>.70 and <.26 on the other factor).

For the Turkish-Dutch minority group, two factors were also found and these accounted for 53.4% and 22.9% of the variance, respectively. The three items on life satisfaction in the Netherlands loaded high on the first factor (>.87) and had a load of <.19 on the second factor. The three other items loaded on the second factor (>.80, and <.29 on the other factor). Hence, for the six items the factor analysis confirmed that a distinction can be made between life satisfaction in the Netherlands and general life satisfaction. This was found for both groups and Tucker’s phi was .95.

For life satisfaction in the Netherlands, Cronbach’s alpha was .82 for the majority group, and .89 for the ethnic minorities. For general life satisfaction, alpha was .68 for the former group and .76 for the latter one. Similar to Study 1, both scales were statistically significant and positively related (r = .39, p < .001) but, again, the amount of shared variance was limited.

5.2 Mean Scores

To examine the mean score for ethnic identification, we used analysis of variance with ethnic group, gender and age as factors. There were no age and gender differences, but the Turkish-Dutch participants (M = 3.96, SD = .67) had higher ethnic identification than the Dutch (M = 3.36, SD = .51), F(1, 208) = 39.28, p < .001.

The mean score for structural discrimination as perceived by the Turkish-Dutch participants was 2.88 (SD = .72). Thus, on a 5-point scale, the Turkish-Dutch indicated moderate levels of structural discrimination.

5.3 Life in the Netherlands

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to predict life satisfaction in the Netherlands. On the first step, the effects of gender, age and ethnic group were entered as factors. Gender and ethnic group were dummy-coded with respectively males and the Dutch as comparison group. The measure for ethnic identification was entered on the second step, and on Step 3 the interaction between ethnic group and group identification was included in the regression model.

The model on the first step explained 4.4% of the variance, F change(3, 205) = 3.14, p < .05. Gender and age were no significant predictors, but ethnic group had a significant effect (β = −.17, t = 2.43, p < .05). The Turkish-Dutch participants (M = 4.98, SD = 1.23) were significantly less satisfied with their lives in the Netherlands than the Dutch (M = 5.60, SD = .98).

The addition of the measure of ethnic identification on Step 2 significantly increased the explained variance, \( R^{2}_{{{\text{change}}}} \) = .02, F change(1, 204) = 3.85, p < .05. Higher group identification was positively related to life satisfaction in the Netherlands (β = .15, t = 2.02, p < .05). Further, the effect for ethnic group remained significant and became somewhat stronger (β = −.26, t = 3.09, p < .01). However, these effects were qualified by a significant interaction effect between ethnic group and ethnic identification on Step 3, \( R^{{\text{2}}}_{{{\text{change}}}} \) = .02, F change(1, 203) = 4.27, p < .05. Separate analyses for the Dutch and the Turkish-Dutch participants indicated that for the Dutch ethnic identification was positively related to life satisfaction in the Netherlands (β = .29, t = 3.03, p < .01). For the Turkish-Dutch, no significant association was found (β = .01, t = .01, p > .10).

5.4 General Life Satisfaction

A hierarchical regression analysis predicted general life satisfaction. The effects of gender, age and ethnic group were entered on Step 1. The measure of life satisfaction in the Netherlands was entered on Step 2 and the one for ethnic identification on Step 3. The interaction between ethnic group and ethnic identification was included in the fourth model.

The model on the first step explained 7.1% of the variance in general life satisfaction, F change(3, 205) = 5.20, p < .01. Gender was not a significant predictor but older respondents indicated lower general life satisfaction compared to younger respondents (β = −.14, t = 2.05, p < .05). In addition, Dutch respondents had higher general life satisfaction than the Turkish-Dutch (β = −.14, t = 2.08, p < .05; M = 5.56, SD = 1.60, and M = 5.08, SD = 1.61, respectively).

The addition of the measure of life satisfaction in the Netherlands on Step 2 significantly increased the explained variance, \( R^{2}_{{{\text{change}}}} \) = .14, F change(1, 204) = 36.91, p < .001. Higher life satisfaction in the Netherlands was positively associated with general life satisfaction (β = .39, t = 6.08, p < .001). Age remained a significant negative predictor (β = −.14, t = 2.04, p < .05), whereas, and similar to Study 1, the effect for ethnic group was no longer significant (β = −.07, t = 1.21, p > .10).

On Step 3, the measure of ethnic identification accounted for an additional and significant part of the variance, \( R^{2}_{{{\text{change}}}} \) = .05, F change(1, 203) = 13.15, p < .001. Stronger ethnic identification was positively associated with general life satisfaction (β = .25, t = 3.63, p < .001. This effect was qualified, however, by the significant interaction between ethnic group and ethnic identification on Step 4, \( R^{2}_{{{\text{change}}}} \) = .02, F change(1, 202) = 4.07, p < .05. Separate analyses for the Dutch and the Turkish-Dutch participants indicated that for the Dutch, ethnic identification was not related to general life satisfaction (β = .07, t = .71, p > .10), whereas for the Turkish-Dutch a positive association was found (β = .35, t = 4.04, p < .001).

5.5 The Turkish-Dutch

To examine the responses of the Turkish-Dutch in more detail and to consider the role of perceived structural discrimination, additional hierarchical regression analyses were conducted with length of residence (born in the Netherlands versus not born in the Netherlands), passport nationality and perceived discrimination as additional predictors. Passport nationality was dummy-coded into two variables such that the Turkish nationality was the referent group.

A first analysis predicted life satisfaction in the Netherlands. There were no differences for gender, age, passport nationality and for length of residence. However, perceived structural discrimination was significantly and negatively related to life satisfaction in the Netherlands (β = −.21, t = 2.07, p < .05).

A second regression analysis was conducted to predict general life satisfaction. The effects of gender, age, length of residence, and passport nationality were entered on Step 1, and the main effects of perceived discrimination, ethnic identification, and life satisfaction in the Netherlands were entered on Step 2. Similar to Study 1, the model in the first step did not explain a significant part of the variance in general life satisfaction, F change(5, 99) = 1.09, p > .10. Thus, there were no effects for gender, age, length of residence and nationality on general life satisfaction. The addition of the two measures on Step 2 significantly increased the explained variance, \( R^{2}_{{{\text{change}}}} \) = .26, F change(3, 96) = 12.07, p < .001. Satisfaction in the Netherlands and ethnic identification were both positively associated to general life satisfaction (β = .36, t = 4.14, p < .001, and β = .39, t = 4.27, p < .001, respectively). Perceived discrimination had no longer a significant independent effect (β = −.02, t = .18, p > .10).

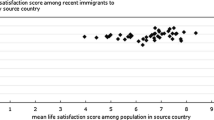

We included the significant predictors in a path model for influences on general life satisfaction (Fig. 1). We based the model on the different regression equations. The partial correlation coefficients on the paths show the relative effects of the predictor variables on the endogenous variables, with the other variables influencing them held statistically constant. The upper pathway showed a negative effect of perceived structural discrimination on life satisfaction in the Netherlands, which, in turn is positively associated with general life satisfaction. The lower pathway indicated a positive effect of perceived discrimination on ethnic identification, and, with stronger ethnic identification leading to more positive general life satisfaction.

5.6 Discussion

The results of the second study are quite similar to those of the first, but also go beyond the first study by focusing on ethnic group identification and perceived structural discrimination. Turkish-Dutch participants had, again, lower general life satisfaction than the Dutch and this was due to them being less satisfied with their life in the Netherlands. There was no ethnic group difference in general life satisfaction after life satisfaction in the Netherlands was taken into account statistically.

For the Dutch, ethnic group identification was positively related to life satisfaction in the Netherlands but not to general life satisfaction. In contrast, for the Turkish-Dutch, ethnic identification was positively related to general life satisfaction only. In addition, for the Turkish-Dutch group, perceived structural discrimination was related to general life satisfaction via its negative effect on life satisfaction in the Netherlands and its positive effect on ethnic identification.

6 General Discussion

Relatively few studies have examined the life satisfaction of immigrant and ethnic minority groups. The existing research tends to find, however, lower life satisfaction among these groups, also after controlling for factors such as income, educational level, age and gender (e.g., Andrews and Withey 1976; Campbell et al. 1976; Ullman and Tatar 2001; Verkuyten 1989). Hence, it appears that being an ethnic minority group member carries additional factors that lower general life satisfaction. For most immigrants and ethnic minority groups, everyday live in the country of settlement is a central issue because it raises questions of belonging and acceptance and of psychological and sociocultural adaptation. Minority group members are well aware of the fact that their group is devalued in society and that they can become the targets of discrimination by the majority group.

The results of the two studies show that Turkish-Dutch participants had lower life satisfaction than the Dutch. This appears to be due to them feeling less satisfied with living in the Netherlands. Furthermore, perceived structural discrimination was negatively related to life satisfaction in the Netherlands. So it turns out that the Turkish-Dutch have lower general life satisfaction because they perceive structural discrimination by the majority group which makes that they are less satisfied with their life in the Netherlands. In addition, and in agreement with the rejection-identification model (Branscombe et al. 1999, see also Verkuyten and Nekuee 1999), higher perceived discrimination was related to a stronger Turkish group identification. In turn, group identification was positively associated with general life satisfaction. Ethnic group identification seems to play a role in life satisfaction because people attribute value to their ethnic group and derive satisfaction from their belongingness and sense of inclusion. Thus, perceived discrimination appears to have a combined effect of lowering general life satisfaction by its negative impact on life satisfaction in the Netherlands, and enhancing general life satisfaction by increasing group identification (see Fig. 1).

In this paper a bottom-up approach was used which raises questions of domain identification. There are various proposals for a distinction between domains of life but these have not considered the experiences of immigrants and ethnic minorities (e.g. Argyle 1987; Cummins 1996). Distinctions such as between family life, work and occupation, health, and environment are typically made. In addition, in his seven-domain partition Cummins (1996) has argued for ‘place in community’ as a separate domain. He indicates that this domain reflects the influence of large-scale social structures, status hierarchies and societal pressures on life satisfaction. This comes close to our current interest. What is crucial, however, is that the domains of life distinguished relate to the way people think about their lives. For many immigrants and ethnic minority groups this involves their life in the country of settlement and being in a minority position in society as well as their feelings of belongingness and solidarity with their own minority group (Verkuyten 2005).

To evaluate the present findings and to give some suggestions for further study, two limitations of our research will be considered. First, we used a bottom-up approach but the data are correlational. Thus, it is possible that general life satisfaction affects the way people feel about living in a ‘new’ country. However, it seems reasonable to assume that a bottom-up impact exist and that the way that immigrant and minority group members feel about their life in the country of settlement influences their general life satisfaction. It is also unlikely that general life satisfaction influences ethnic group identification. However, group identification plays a complex role in how members of minority groups construe and cope with being a target of rejection and discrimination. For example, ethnic identification implies a stronger group focused orientation which can increase the likelihood that individuals perceive rejection or attribute ambiguous events to discrimination (e.g., Eccleston and Major 2006; Major et al. 2002).

Second, the focus was on a single domain of life and one particular minority group. Hence, it is unclear what the role is of other domains of live and whether these findings generalize to other groups and settings. Future studies could focus on other domains of life that can be sources as well as threats to general life satisfaction of immigrant and ethnic minority groups. Turkish-Dutch people, for example, have been found to emphasize family integrity and their religious identity and involvement (Phalet et al. 2000), and both can be important contingencies to base one’s life satisfaction upon. In contrast, job and employment and education can be domains where minority groups members are uncertain and vigilant in their relations with the majority group, until they have reason to believe that majority members are worthy of their trust (e.g., Cohen and Steele 2002). Future studies could also focus on other ethnic minority groups in other countries. Not all ethnic minority groups, for example, are evaluated similarly and enjoy similar degrees of social acceptance and discrimination. Evidence for this exist in countries such as Canada, the United States, the former Soviet Union, and the Netherlands (for reviews see Hagendoorn 1995; Owen et al. 1981). In the latter country, for example, Moroccans and Turks are the least accepted but groups such as Surinamese and Antilleans are relatively more accepted.

There are also country differences in immigration and integration policies and in the way that the national identity is defined. For example, in contrast to a civic conception of nationality an ethnic one makes it more difficult for immigrants to combine the notion of national identity with that of a distinctive ethnic identity. In their research among more than 7000 immigrants in 13 countries, Phinney et al. (2006) found statistically negative associations between ethnic minority and national identity in countries such as the Netherlands, Germany and France, whereas in traditional settler countries such as Australia and the US significant positive associations were found. These country differences may also affect the life satisfaction of ethnic minority group members. Thus, future studies on both the origins and correlates of life satisfaction among different immigrant and ethnic groups in different settings and countries should contribute to a further understanding of the ways that a minority position affects life satisfaction.

To conclude, using data from two studies the present paper has demonstrated that ethnic minority group members have lower general life satisfaction than the majority group because they are less satisfied with their life in the country in which they reside. Higher perceived structural discrimination was found to be associated with lower life satisfaction in the country of settlement, but also with higher ethnic group identification that, in turn, made a positive contribution to general life satisfaction.

References

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: America’s perception of life quality. New York: Plenum Press.

Argyle, M. (1987). The psychology of happiness. London: Methuen.

Berry, J. W. (2001). A psychology of immigration. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 611–627.

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Harvey, R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implication for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2005). Webmagazine, October 10th, 2005.

Cohen, G. L., & Steele, C. M. (2002). A barrier of mistrust: How negative stereotypes affect cross-race monitoring. In: J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education (pp. 303–327). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38, 303–328.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 45, 542–575.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Eccleston, C. P., & Major, B. N. (2006). Attributions to discrimination and self-esteem: The role of group identification and appraisals. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 9, 147–162.

Hagendoorn, L. (1995). Intergroup biases in multiple group systems: The perception of ethnic hierarchies. In: W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (pp. 199–228). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Headley, B., & Veenhoven, R. (1989). Does happiness induce a rosy outlook? In: R. Veenhoven (Ed.), How harmful is happiness? (pp. 106–127). Rotterdam: Universitaire Pers Rotterdam.

Headley, B., Veenhoven, R., & Wearing, A. (1991). Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Social Indicators, 24, 81–100.

Lance, C. E., Mallard, A. G., & Michalos, A. C. (1995). Tests of the causal directions global-life facet satisfaction relationships. Social Indicators Research, 34, 69–92.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 302–318.

Major, B., Quinton, W. J., & McCoy, S. K. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of attributions to discrimination: Theoretical and empirical advances. In: M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 251–330). New York: Academic Press.

Michalos, A. C., & Zumbo, B. D. (2001). Ethnicity, modern prejudice and the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 53, 189–222.

Owen, C., Eisner, H., & McFaul, T. (1981). A half-century of social distance research: National replication of the Bogardus studies. Sociology and Social Research, 66, 80–98.

Phalet, K., Van Lotringen, C. & Entzinger, H. (2000). Islam in de multiculturele samenleving: Opvattingen van jongeren in Rotterdam (Islam in the multicultural society: Attitudes of youth in Rotterdam). Utrecht, The Netherlands: Ercomer.

Phinney, J. S., Berry, J. W., Vedder, P., & Liebkind, K. (2006). The acculturation experience: Attitudes, identities and behaviors of immigrant youth. In J. W. Berry, J. S. Phinney, D. L. Sam, & P. Vedder (Eds.), Migrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts (pp. 71–116). Hamwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Rojas, M. (2006). Life satisfaction and satisfaction in domains of life: Is it a simple relationship? Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 467–497.

Sam, D. L., Vedder, P., Ward, C., & Horenczyk, G. (2006). Psychological and sociocultural adaptation of immigrant youth. In: J. W. Berry, J. S. Phinney, D. L. Sam, & P. Vedder (Eds.), Migrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts (pp. 117–142). Hamwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Scherpenzeel, A., & Saris, W. (1996). Causal direction in a model of life satisfaction: The top-down/bottom-up controversy. Social Indicators Research, 38, 161–180.

Schmitt, M. T., & Branscombe, N. R. (2002). The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged social groups. In: W. Stroebe, & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (Vol. 12, pp. 167–199). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Ullman, C., & Tatar, M. (2001). Psychological adjustment among Israeli adolescent immigrants: A report on life satisfaction, self-concept and self-esteem. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 449–464.

Van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research. London: Sage.

Vedder, P., Van de Vijver, F., & Liebkind, K. (2006). Predicting immigrant youths’ adaptation across countries and ethnocultural groups. In J. W. Berry, J. S. Phinney, D. L. Sam, & P. Vedder (Eds.), Migrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts (pp. 143–166). Hamwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Verkuyten, M. (1986). The impact of ethnic and sex differences on happiness among adolescents in the Netherlands. Journal of Social Psychology, 126, 259–260.

Verkuyten, M. (2005). The social psychology of ethnic identity. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Verkuyten, M., & Nekuee, S. (1999). Subjective well-being, discrimination and cultural conflict: Iranians living in the Netherlands. Social Indicators Research, 47, 281–306.

Verkuyten, M., & Zaremba, K. (2005). Interethnic relations in a changing political context. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68, 375–386.

Ward, C. (1996). Acculturation. In D. Landis, & R Bhagat (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (2nd ed., pp. 124–147). Thousand Oakes: Sage.

Wu, C.-H., & Yao, G. (2006). Do we need to weight satisfaction scores with importance ratings? Social Indicators Research, 78, 305–326.

Wu, C.-H., & Yao, G. (2007). Examining the relationship between global and domain measures of quality of life by three factor structure models. Social Indicators Research, 84, 189–202.

Zheng, X., Sang, D., & Wang, L. (2004). Acculturation and subjective well-being of Chinese students in Australia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 57–72.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Verkuyten, M. Life Satisfaction Among Ethnic Minorities: The Role of Discrimination and Group Identification. Soc Indic Res 89, 391–404 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9239-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9239-2