Abstract

Objective

Chicken astroviruses have been known to cause severe disease in chickens leading to increased mortality and “white chicks” condition. Here we aim to characterize the causative agent of visceral gout suspected for astrovirus infection in broiler breeder chickens.

Methods

Total RNA isolated from allantoic fluid of SPF embryo passaged with infected chicken sample was sequenced by whole genome shotgun sequencing using ion-torrent PGM platform. The sequence was analysed for the presence of coding and non-coding features, its similarity with reported isolates and epitope analysis of capsid structural protein.

Results

The consensus length of 7513 bp genome sequence of Indian isolate of chicken astrovirus was obtained after assembly of 14,121 high quality reads. The genome was comprised of 13 bp 5′-UTR, three open reading frames (ORFs) including ORF1a encoding serine protease, ORF1b encoding RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and ORF2 encoding capsid protein, and 298 bp of 3′-UTR which harboured two corona virus stem loop II like “s2m” motifs and a poly A stretch of 19 nucleotides. The genetic analysis of CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 suggested highest sequence similarity of 86.94% with the chicken astrovirus isolate CAstV/GA2011 followed by 84.76% with CAstV/4175 and 74.48%% with CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolates. The capsid structural protein of CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 showed 84.67% similarity with chicken astrovirus isolate CAstV/GA2011, 81.06% with CAstV/4175 and 41.18% with CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolates. However, the capsid protein sequence showed high degree of sequence identity at nucleotide level (98.64-99.32%) and at amino acids level (97.74–98.69%) with reported sequences of Indian isolates suggesting their common origin and limited sequence divergence. The epitope analysis by SVMTriP identified two unique epitopes in our isolate, seven shared epitopes among Indian isolates and two shared epitopes among all isolates except Poland isolate which carried all distinct epitopes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poultry meat production is increasing globally day by day as it is easily manageable animal protein source for human consumption compared to others. However, viral diseases incurs heavy economic losses to the poultry industry. Among the different viruses infecting birds, astroviruses are small round viruses, characterized based on its morphology (Caul and Appleton 1982). Astrovirus was first observed in human during 1975 in faeces of the infant suffering from gastroenteritis (Madeley and Cosgrove 1975). They are broadly categorized into two genera, Mammoastrovirus infecting mammals and Aviastrovirus infecting avian species. Both of these genera belongs to the family Astroviridae. Astroviruses can infect variety of host including human ((Finkbeiner et al. 2008; Madeley and Cosgrove 1975), cattle (Bouzalas et al. 2014; Li et al. 2013; Schlottau et al. 2016), sheep (Jonassen et al. 2003; Reuter et al. 2012), cat (Hoshino et al. 1981; Lau et al. 2013), dog (Martella et al. 2012; Takano et al. 2015) and deer (Smits et al. 2010).

Mammoastrovirus are mostly associated with gastroenteritis in the host. However, Aviastrovirus can cause different diseases in the different host. The members of genus Aviastrovirus mainly infects turkey, chicken and duck. Turkey Astrovirus (TAstV) causes Poultry Enteritis Mortality Syndrome (PEMS) or Poultry Enteritis Syndrome (PES) (McNulty et al. 1980; Mor et al. 2011) while in duck, astroviruses (DAstV) are associated with hepatitis (Asplin 1965; Gough et al. 1984, 1985). In chickens, two astrovirus species avian nephritis virus (ANV) (Imada et al. 2000; Shirai et al. 1991) and Chicken Astrovirus (CAstV) (Baxendale and Mebatsion 2004) have been reported. Initially CAstV was accepted as enterovirus causing growth retardation (Schultz-Cherry et al. 2001; Todd et al. 2009). Later on it was also found to be associated with gout (Bulbule et al. 2013) and hatchability problem (Smyth et al. 2013) in broiler chickens. Recently CAstV has been linked with ‘white chicks’, a disease characterized by weakness and white plumage of hatched chicks (Smyth et al. 2013) and leading to increased mortality in chicks and embryo has also been reported in Poland (Sajewicz-Krukowska et al. 2016) and Brazil (Nunez et al. 2016).

Chicken astroviruses are non-enveloped, 25–35 nm in diameter and contain non-segmented positive sense ssRNA genome comprised of 6.8 to 7.9 kb in length (Matsui and Greenberg 2001; Mendez et al. 2007). Whole genome sequencing and other studies have revealed that the basic structure and molecular mechanism is almost similar for all the astroviruses sequenced till date (Koci et al. 2000). Initially there was no authentic diagnostic method available for astrovirus which relied mostly on electron microscopy (Madeley and Cosgrove 1975; McNulty et al. 1980) or immunoassay (Baxendale and Mebatsion 2004). However, advances in the molecular biology have led to the development of some easy techniques for detection of viruses. Astroviruses can also be diagnosed using RT-PCR (Pantin-Jackwood et al. 2008; Smyth et al. 2009; Todd et al. 2009). Lee et al. (2013) suggested that a recombinant capsid can be used for diagnosis and vaccination. Till now the genome of only three chicken astroviruses CAstV/4175 (directly submitted to NCBI), CAstV/GA2011 (Kang et al. 2012) and CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 (Sajewicz-Krukowska and Domanska-Blicharz 2016) have been reported. In this study, we sequenced and characterized whole genome of chicken astrovirus isolated from infected broiler chicks from western part of India.

Materials and methods

History and sample collection

A broiler breeder farm at Anand, Gujarat, India was facing the problem of visceral gout in the Cobb-400 commercial chicks from last three batches of the parents. The outbreaks were noticed only in the initial hatches of the parents aging 28 to 32 weeks of age. These parents were vaccinated with infectious bronchitis nephropathic vaccine strains. The fertility and hatchabilities were normal but the chicks started showing lameness with spiking mortality from 4th day onward. Mortality continued for 5–7 days and ranged from 5 to 25%. Hatches falling during winter season i.e. November to February had high mortality. Dead chicks showed increased amount of abdominal fluid, pale and greyish kidneys with dilated tubules filled with urates. Chalky white deposits of urates were found on serosal surfaces of pericardium, liver capsule, air sacs, joint capsules and mucosal surfaces of proventriculus, trachea etc. Affected chick sample was submitted to Hester Biosciences limited for diagnosis of infection during the period of February 2016. The spleen, kidney and lungs tissue samples from the freshly dead birds were collected and triturated in PBS to make a 10% solution, then passed through the 0.22 μm syringe filter and inoculated in 10 day embryonated SPF eggs through allantoic cavity route. After three blind passages, the embryos started dying 5 to 6 days post inoculation and showed haemorrhagic lesion on the body surface. The allantoic fluid from the dead embryo was collected and used for total RNA isolation for subsequent analysis by whole genome sequencing.

Library preparation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA, USA) and treated with RNase free DNase I (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to remove any DNA contamination. Total RNA thus obtained was subjected to RNAseq library preparation as per the Ion total RNAseq kit v2 (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The sequencing was carried on Ion torrent PGM using 316 chip (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

De novo assembly, gene prediction and annotation

The sequencing reads generated from the sequencer were subjected to mapping with Gallus gallus genome (WGS: INSDC: AADN00000000.4) to remove the host sequences. Remaining sequences were subjected to quality filtering Q > 25 using PRINSEQ v0.20.4 and good quality sequences were de novo assembled using GS de novo assembler. The assembled genome sequence was searched for BLASTN similarity against nr/nt database. The genome sequence was further analysed for prediction of putative open reading frames (ORF) by ORF finder tool (Stothard 2000) and manual curation for the analysis of ribosomal frameshift signal (RFS) as reported for other astroviruses (Koci et al. 2000; Sajewicz-Krukowska and Domanska-Blicharz 2016). The prediction of stem loop structure of RFS was performed by RNAfold web server (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi). Non-coding RNA sequences were inferred using similarity search against Rfam database (Nawrocki et al. 2015).

Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analysis

A nearly complete genome sequences of 11 astroviruses (Table 1) were downloaded from the NCBI and predicted for presence of ORFs using ORFfinder tool and manual curation of RFS start site. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal Omega webserver (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) to analyse the percent identity with other genomes at nucleotide and amino acids level. Phylogenetic analysis of genomes and predicted proteins were performed in MEGA6 (Tamura et al. 2013) after building alignment by clustalw algorithm and subsequent tree generation using neighbour joining method (Saitou and Nei 1987) with 1000 bootstraps replicates. Nucleotide sequences of ORF2 encoding capsid protein of reported Indian isolates were retrieved from NCBI nr database and analysed for nucleotide and amino acids similarity and phylogeny as described earlier.

Linear antigen epitope prediction and comparative analysis with other chicken astroviruses

We used SVMTriP (Yao et al. 2012) which predict linear antigen epitope based on Support Vector Machine to integrate Tri-Peptide Similarity and Propensity. Capsid protein sequence was used for epitope prediction. We compared epitopes of three CAstV isolates from India [CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016, VRDC|CAstV|NZ|VHINP-4 (Accession No. AGB58310.1) South region (Accession No. AIC32814.1)], two from USA (CAstV/GA2011 and CAstV/4175), one from UK (accession No.AFK92952.1) and one from Poland (CAstV/Poland/G059/2014).

Results

Identification of causative agent of visceral gout in broiler chickens

Allantoic fluid collected from SPF embryo inoculated for three blind passages of field sample was subjected to total RNA isolation and next generation sequencing using ion torrent platform resulted in a total of 108,109 reads with average read length of 180 bases. After removing the host specific and low quality reads, a total of 14,121 reads were used for assembly. The genome was assembled into a consensus length of 7513 bp which was identified as Chicken astrovirus upon nucleotide blast analysis. The full length genome sequence was deposited to the GenBank under the accession number KY038163. There was an untranslated region (UTR) of 13 bp at 5′ end and of 298 bp at 3′ end with a poly-A tail stretch of 19 nucleotides. The genome was composed of A (30%, 2307 nt), T (29% 2034 nt), G (23%, 1769 nt) and C (18% 1403 nt) with a GC content of 42.2%.

Genome sequence analysis of identified chicken astrovirus isolate for the presence of coding and non-coding features

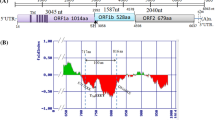

The genome encoded three ORFs (ORF1a, ORF1b and ORF2) with each ORF encoding for single protein coding gene and a partial overlap of ORF1b with ORF1a (Fig. 1a). Manual curation of the ribosomal frameshift signal (position nt 3415) revealed presence of ATG start codon preceding the slippery heptameric sequence (AAAAAAC) (Fig. 1b) followed by sequences forming the stem loop structure as predicted by RNAfold analysis (Fig. 1c). Among the analysed genomes, all four chicken astroviruses and duck astrovirus SL5 isolate were found to possess their own ATG start codon for ORF1b whereas it was found absent in other astroviruses (Fig. 1b). Analysis of 3′-UTR by Rfam analysis revealed presence of two non-coding RNAs similar to “s2m” RNA family (Accession number: RF00164) at positions 7192–7234 (e value: 1.5E−14) and 7287–7329 (e value: 8.1E−14).

Similarity of identified chicken astrovirus isolate with known avian astrovirus isolates

Analysis of nucleotide similarity with other full length astroviruses genomes (Table 1) revealed highest identity of 86.94% with CAstV/GA2011 followed by 84.76% with CAstV/4175 and 74.48% with CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 among the chicken astroviruses. The genome showed 54.47–57.55%, 53.94–54.20% and 46.34–47.57% similarity with duck astroviruses, turkey astroviruses and avian nephritis viruses, respectively. The ORF2 coding sequence showed 98.64–99.32% identity with the reported ORF2 sequence of the Indian isolates (Table 2).

Analysis of amino acids sequence similarity of CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 with other avian astroviruses suggested 92.98–96.31% similarity with ORF1a encoded serine protease, 87.26–97.69% with ORF1b encoded RdRp and 41.18–84.67% with ORF2 encoded capsid protein of chicken astroviruses (Table 1). Among the three proteins, RdRp showed highest similarity of 53.53–71.95%, followed by serine protease (30.01–58.17%) and capsid protein (28.62–38.33%) with other avian astroviruses. Among the Indian chicken astrovirus isolates, highly variable capsid protein showed 98.64–99.32% sequence identity at nucleotide level and 97.74–98.69% sequence identity at amino acids level with CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 isolate (Table 2).

Phylogenetic analysis of identified chicken astrovirus isolate

Phylogenetic analysis of the astrovirus genomes suggested formation of separate cluster of chicken astroviruses and placed CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 nearest to the CAstV/4175 isolate (Fig. 2). Similarly, phylogeny based on amino acids sequence of serine protease (Fig. 3a), RdRp (Fig. 3b) and capsid protein (Fig. 3c) showed close clustering among the chicken astroviruses except capsid protein of CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolate which was clustered with the DAstV/SL5 isolate. Among the Indian isolates, ORF2 nucleotide sequence of the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 placed nearest to the VRDC/CAstV/NZ/VHINP-4 isolate (Fig. 4a) whereas based on the amino acid sequence, it was placed nearest to the VRDC/CAstV/NZ/VHINP-7 isolate (Fig. 4b).

B-cell epitope analysis of capsid structural protein of identified chicken astrovirus isolate

A total of 9–10 epitopes were predicted using SVMTriP using the capsid protein sequence of the astroviruses. Epitope analysis revealed two unique epitopes in case of the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016. Epitopes present at the positions 151–170 and 176–195 were common to all of the viruses analysed. Based on the epitopes predicted, CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 was found to be unique as it has not shared any epitopes with other viruses. Comparison of the three Indian CAstVs revealed that seven epitopes were common to all the three and a epitope 649–668 was differing by one amino acid substitution in the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 (Supplementary table 1).

Discussion

The poultry viral diseases have great economic impact on poultry industries worldwide as it leads to high mortality. Chicken astrovirus causes severe disease especially in young chickens (Bulbule et al. 2013; Li et al. 2013; Nunez et al. 2016; Schultz-Cherry et al. 2001; Smyth et al. 2013; Todd et al. 2009). Though culturing methods has been described for astroviruses (Baxendale and Mebatsion 2004; Nunez et al. 2015), the isolation of virus is somewhat difficult due to its poor growth in the culture (Smyth et al. 2010). Next generation sequencing technology is sophisticated as there is no need to isolate or culture the organism. Hence in the present study we directly isolated RNA from allantoic fluid of chicken embryo inoculated with clinical sample and sequenced on Ion torrent PGM platform.

The viral genome of CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 was assembled into 7513 bp which is comparable with the size of other published astrovirus genomes (Chen et al. 2012; Finkbeiner et al. 2008; Sajewicz-Krukowska and Domanska-Blicharz 2016; Strain et al. 2008). The genome showed presence of three ORFs encoding for serine protease, RdRp and capsid protein as reported for other astroviruses. The RdRp of most astroviruses do not have its own start codon. Kang et al. (2012) reported that RdRp of chicken astrovirus GA2011 has its own start codon. We observed presence of ATG start codon for RdRp among all the reported chicken astroviruses and DAstV/SL5 isolate whereas other duck astrovirus and avian nephritis viruses were found to lack ATG start codon. The RNA family analysis by Rfam suggested presence of two motifs matching to corona virus stem loop II (s2m) motif in the 3′-UTR as reported for other astroviruses (Jonassen et al. 1998; Sajewicz-Krukowska and Domanska-Blicharz 2016). Although, exact function is still not uncovered, the presence of these “s2m” motifs is believed to influence gene expression through RNA-interference mechanism (Tengs et al. 2013)

Based on the nucleotide similarity, the virus was found to be closest to the chicken astrovirus isolate GA2011 (Kang et al. 2012) followed by CAstV/4175 (direct submission) and CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 (Sajewicz-Krukowska and Domanska-Blicharz 2016) among the chicken astroviruses. At amino acids level, serine protease and capsid protein of the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 virus showed highest identity with chicken astrovirus isolate GA2011 followed by CAstV/4175 and CAstV/Poland/G059/2014, whereas RdRp showed maximum identity with the chicken astrovirus isolate GA2011 followed by CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 and CAstV/4175 isolates. Capsid protein of the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 isolate showed only 41.18% identity with the CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolate. Sajewicz-Krukowska and Domanska-Blicharz (2016) suggested that this limited identity of capsid protein of the CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolate with other chicken astrovirus capsid protein but higher identity with the duck astroviruses may be due a recombination event and shared ancestors with the duck astroviruses. Among the avian astroviruses, chicken astroviruses were found to share higher identity with the duck astroviruses (Chen et al. 2012; Fu et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2014) as compared to the turkey astroviruses (Koci et al. 2000; Strain et al. 2008) and the avian nephritis virus isolates (Imada et al. 2000; Zhao et al. 2011a, b). We next analysed the sequence similarity of capsid structural protein of the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 with the capsid protein coding sequence and amino acids sequence of reported sequence of the Indian astrovirus isolates which revealed about 98–99% sequence identity at nucleotide level and about 97–98% sequence identity at amino acids level suggesting limited structural divergence and their common origin in the Indian isolates reported till date.

Phylogenetic analysis of the genome sequences as well as the protein sequences showed clustering of the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 nearest to that of CastV/4175 and CAstV/GA2011 and all four chicken astrovirus formed separate cluster except capsid protein of the CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolate which was clustered along with the duck astroviruses. The clustering of CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 with the duck astrovirus isolate SL5 suggest possible recombination between these isolates (Sajewicz-Krukowska and Domanska-Blicharz 2016). Based on nucleotide sequence of genomes and amino acids sequence of serine protease and RdRp, Chicken astroviruses were placed closed to the duck astroviruses compared to turkey astroviruses or avian nephritis viruses. However, based on capsid protein the turkey astroviruses were phylogenetically placed between different isolates of the duck astroviruses as well as near to the CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolate. These observations suggest that the capsid protein of turkey, duck and chicken astroviruses evolved through possible recombination between the astroviruses of different avian species and suggests that the turkey and duck may play an important role in epidemiology of avian astroviruses similar to that of influenza viruses (Alexander 2000). Among the Indian isolates, phylogenetic analysis of capsid protein showed placement of the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 between two north zone isolates, however very limited sequence divergence was seen among the reported Indian isolates suggesting their recent emergence and common origin.

Epitope analysis of the capsid protein sequence revealed two unique epitopes in our isolate whereas 7 epitopes were found to be shared among the Indian astrovirus isolates. Except CAstV/Poland/G059/2014 isolate which contained all unique epitopes, other isolates shared two common epitopes. Our analysis suggests that the vaccine design using the Indian astrovirus isolate may provide cross protection against prevailing isolates in India. Further, epitope mapping would be useful to design safe and effective vaccine against divergent astroviruses (Ahmad et al. 2016; Soria-Guerra et al. 2015).

In summary, whole genome analysis of Indian astrovirus isolate by next generation sequencing technology determined full length genome of the chicken astrovirus isolate for the first time in India. The present study provided genetic relatedness of the circulating Indian isolate with the other reported nearly complete genome sequences of avian astroviruses. The analysis of capsid protein sequence of reported chicken astroviruses from India revealed limited structural divergence suggesting their common ancestral origin and recent emergence. Considering high sequence identity of capsid structural protein among prevailing strains in the India, the CAstV/INDIA/ANAND/2016 isolate could serve as the potential source for its further development as a vaccine candidate. The identification of unique and shared epitopes among different astroviruses will be helpful in designing effective epitope based vaccine formulation.

References

Ahmad TA, Eweida AE, Sheweita SA (2016) B-cell epitope mapping for the design of vaccines and effective diagnostics. Trials Vaccinol 5:71–83

Alexander DJ (2000) A review of avian influenza in different bird species. Vet Microbiol 74:3–13

Asplin FD (1965) Duck hepatitis: vaccination against two serological types. Vet Rec 77:1529–1530

Baxendale W, Mebatsion T (2004) The isolation and characterisation of astroviruses from chickens. Avian Pathol 33:364–370. doi:10.1080/0307945042000220426

Bouzalas IG et al (2014) Neurotropic astrovirus in cattle with nonsuppurative encephalitis in Europe. J Clin Microbiol 52:3318–3324. doi:10.1128/JCM.01195-14

Bulbule NR, Mandakhalikar KD, Kapgate SS, Deshmukh VV, Schat KA, Chawak MM (2013) Role of chicken astrovirus as a causative agent of gout in commercial broilers in India. Avian Pathol 42:464–473. doi:10.1080/03079457.2013.828194

Caul EO, Appleton H (1982) The electron microscopical and physical characteristics of small round human fecal viruses: an interim scheme for classification. J Med Virol 9:257–265

Chen L et al (2012) Complete genome sequence of a duck astrovirus discovered in eastern China. J Virol 86:13833–13834. doi:10.1128/JVI.02637-12

Finkbeiner SR, Kirkwood CD, Wang D (2008) Complete genome sequence of a highly divergent astrovirus isolated from a child with acute diarrhea. Virol J 5:117. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-117

Fu Y et al (2009) Complete sequence of a duck astrovirus associated with fatal hepatitis in ducklings. J Gen Virol 90:1104–1108. doi:10.1099/vir.0.008599-0

Gough RE, Collins MS, Borland E, Keymer LF (1984) Astrovirus-like particles associated with hepatitis in ducklings. Vet Rec 114:279

Gough RE, Borland ED, Keymer IF, Stuart JC (1985) An outbreak of duck hepatitis type II in commercial ducks. Avian Pathol 14:227–236. doi:10.1080/03079458508436224

Hoshino Y, Zimmer JF, Moise NS, Scott FW (1981) Detection of astroviruses in feces of a cat with diarrhea. Brief report. Arch Virol 70:373–376

Imada T, Yamaguchi S, Mase M, Tsukamoto K, Kubo M, Morooka A (2000) Avian nephritis virus (ANV) as a new member of the family Astroviridae and construction of infectious ANV cDNA. J Virol 74:8487–8493

Jonassen CM, Jonassen TO, Grinde B (1998) A common RNA motif in the 3′ end of the genomes of astroviruses, avian infectious bronchitis virus and an equine rhinovirus. J Gen Virol 79(Pt 4):715–718. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-79-4-715

Jonassen CM, Jonassen TT, Sveen TM, Grinde B (2003) Complete genomic sequences of astroviruses from sheep and turkey: comparison with related viruses. Virus Res 91:195–201

Kang KI, Icard AH, Linnemann E, Sellers HS, Mundt E (2012) Determination of the full length sequence of a chicken astrovirus suggests a different replication mechanism. Virus Genes 44:45–50. doi:10.1007/s11262-011-0663-z

Koci MD, Seal BS, Schultz-Cherry S (2000) Molecular characterization of an avian astrovirus. J Virol 74:6173–6177

Lau SK, Woo PC, Yip CC, Bai R, Wu Y, Tse H, Yuen KY (2013) Complete genome sequence of a novel feline astrovirus from a domestic cat in Hong Kong. Genome Announc 1 doi:10.1128/genomeA.00708-13

Lee A et al (2013) Chicken astrovirus capsid proteins produced by recombinant baculoviruses: potential use for diagnosis and vaccination. Avian Pathol 42:434–442. doi:10.1080/03079457.2013.822467

Li L et al (2013) Divergent astrovirus associated with neurologic disease in cattle. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1385–1392. doi:10.3201/eid1909.130682

Liu N, Wang F, Zhang D (2014) Complete sequence of a novel duck astrovirus. Arch Virol 159:2823–2827. doi:10.1007/s00705-014-2141-0

Madeley C, Cosgrove B (1975) Viruses in infantile gastroenteritis. Lancet 306:124

Martella V et al (2012) Enteric disease in dogs naturally infected by a novel canine astrovirus. J Clin Microbiol 50:1066–1069. doi:10.1128/JCM.05018-11

Matsui SM, Greenberg HB (2001) Astroviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM (eds) Fields virology, 4th edn. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 875–893

McNulty MS, Curran WL, McFerran JB (1980) Detection of astroviruses in turkey faeces by direct electron microscopy. Vet Rec 106:561

Mendez E, Aguirre-Crespo G, Zavala G, Arias CF (2007) Association of the astrovirus structural protein VP90 with membranes plays a role in virus morphogenesis. J Virol 81:10649–10658. doi:10.1128/JVI.00785-07

Mor SK, Abin M, Costa G, Durrani A, Jindal N, Goyal SM, Patnayak DP (2011) The role of type-2 turkey astrovirus in poult enteritis syndrome. Poult Sci 90:2747–2752. doi:10.3382/ps.2011-01617

Nawrocki EP et al (2015) Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D130–137. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1063

Nunez LF, Parra SH, Mettifogo E, Catroxo MH, Astolfi-Ferreira CS, Piantino Ferreira AJ (2015) Isolation of chicken astrovirus from specific pathogen-free chicken embryonated eggs. Poult Sci 94:947–954. doi:10.3382/ps/pev086

Nunez LF, Santander Parra SH, Carranza C, Astolfi-Ferreira CS, Buim MR, Piantino Ferreira AJ (2016) Detection and molecular characterization of chicken astrovirus associated with chicks that have an unusual condition known as “white chicks” in Brazil. Poult Sci 95:1262–1270. doi:10.3382/ps/pew062

Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Day JM, Jackwood MW, Spackman E (2008) Enteric viruses detected by molecular methods in commercial chicken and turkey flocks in the United States between 2005 and 2006. Avian Dis 52:235–244. doi:10.1637/8174-111507-Reg.1

Reuter G, Pankovics P, Delwart E, Boros A (2012) Identification of a novel astrovirus in domestic sheep in Hungary. Arch Virol 157:323–327. doi:10.1007/s00705-011-1151-4

Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425

Sajewicz-Krukowska J, Domanska-Blicharz K (2016) Nearly full-length genome sequence of a novel astrovirus isolated from chickens with ‘white chicks’ condition. Arch Virol 161:2581–2587. doi:10.1007/s00705-016-2940-6

Sajewicz-Krukowska J, Pac K, Lisowska A, Pikula A, Minta Z, Kroliczewska B, Domanska-Blicharz K (2016) Astrovirus-induced “white chicks” condition - field observation, virus detection and preliminary characterization. Avian Pathol 45:2–12. doi:10.1080/03079457.2015.1114173

Schlottau K, Schulze C, Bilk S, Hanke D, Hoper D, Beer M, Hoffmann B (2016) Detection of a novel bovine astrovirus in a Cow with encephalitis. Transbound Emerg Dis 63:253–259. doi:10.1111/tbed.12493

Schultz-Cherry S, King DJ, Koci MD (2001) Inactivation of an astrovirus associated with poult enteritis mortality syndrome. Avian Dis 45:76–82

Shirai J, Nakamura K, Shinohara K, Kawamura H (1991) Pathogenicity and antigenicity of avian nephritis isolates. Avian Dis 35:49–54

Smits SL, van Leeuwen M, Kuiken T, Hammer AS, Simon JH, Osterhaus AD (2010) Identification and characterization of deer astroviruses. J Gen Virol 91:2719–2722. doi:10.1099/vir.0.024067-0

Smyth VJ, Jewhurst HL, Adair BM, Todd D (2009) Detection of chicken astrovirus by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Avian Pathol 38:293–299. doi:10.1080/03079450903055397

Smyth VJ, Jewhurst HL, Wilkinson DS, Adair BM, Gordon AW, Todd D (2010) Development and evaluation of real-time TaqMan(R) RT-PCR assays for the detection of avian nephritis virus and chicken astrovirus in chickens. Avian Pathol 39:467–474. doi:10.1080/03079457.2010.516387

Smyth V et al (2013) Chicken astrovirus detected in hatchability problems associated with ‘white chicks’. Vet Rec 173:403–404. doi:10.1136/vr.f6393

Soria-Guerra RE, Nieto-Gomez R, Govea-Alonso DO, Rosales-Mendoza S (2015) An overview of bioinformatics tools for epitope prediction: implications on vaccine development. J Biomed Inform 53:405–414

Stothard P (2000) The sequence manipulation suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. Biotechniques 28(1102):1104

Strain E, Kelley LA, Schultz-Cherry S, Muse SV, Koci MD (2008) Genomic analysis of closely related astroviruses. J Virol 82:5099–5103. doi:10.1128/JVI.01993-07

Takano T, Takashina M, Doki T, Hohdatsu T (2015) Detection of canine astrovirus in dogs with diarrhea in Japan. Arch Virol 160:1549–1553. doi:10.1007/s00705-015-2405-3

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst197

Tengs T, Kristoffersen AB, Bachvaroff TR, Jonassen CM (2013) A mobile genetic element with unknown function found in distantly related viruses. Virol J 10:1

Todd D, Wilkinson DS, Jewhurst HL, Wylie M, Gordon AW, Adair BM (2009) A seroprevalence investigation of chicken astrovirus infections. Avian Pathol 38:301–309. doi:10.1080/03079450903055421

Yao B, Zhang L, Liang S, Zhang C (2012) SVMTriP: a method to predict antigenic epitopes using support vector machine to integrate tri-peptide similarity and propensity. PLoS One 7, e45152. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045152

Zhao W et al (2011a) Sequence analyses of the representative Chinese-prevalent strain of avian nephritis virus in healthy chicken flocks. Avian Dis 55:65–69. doi:10.1637/9506-081810-Reg.1

Zhao W et al (2011b) Complete sequence and genetic characterization of pigeon avian nephritis virus, a member of the family Astroviridae. Arch Virol 156:1559–1565. doi:10.1007/s00705-011-1034-8

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to Mr. Rajiv Gandhi, Managing Director and CEO, Hester Biosciences Limited, Ahmedabad, India and Anand Agricultural University, Anand, India for providing the facility to carry out the research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, A.K., Pandit, R.J., Thakkar, J.R. et al. Complete genome sequence analysis of chicken astrovirus isolate from India. Vet Res Commun 41, 67–75 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11259-016-9673-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11259-016-9673-6