Abstract

A total of ten infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) isolates collected from commercial chickens in Italy in 1999 were characterized by RT-PCR and sequencing of the S1 and N genes. Phylogenetic analysis based on partial S1 gene sequences showed that five field viruses clustered together with 793/B-type strains, having 91.3–98.5% nucleotide identity within the group, and one isolate had very close sequence relationship (94.6% identity) with 624/I strain. These two IBV types have been identified in Italy previously. The other three variant isolates formed novel genotype detected recently in many countries of Western Europe. For one of these variant viruses, Italy-02, which afterwards became the prototype strain, the entire S1 gene was sequenced to confirm its originality. In contrast, phylogenetic analysis of more conserved partial N gene sequences, comprising 1–300 nucleotides, revealed different clustering. Thus, three variant IBVs of novel Italy-02 genotype, which had 96.7–99.2% S1 gene nucleotide identity with each other, belonged to three separate subgroups based on N gene sequences. 624/I-type isolate Italy-06 together with Italy-03, which was undetectable using S1 gene primers, shared 97.7% and 99.3% identity, respectively, in N gene region with vaccine strain H120. Only one of the 793/B-type isolates, Italy-10, clustered with the 793/B strain sharing 99.3% partial N gene identity, whereas the other four isolates were genetically distant from them (only 87.7–89.7% identity) and formed separate homogenous subgroup. The results demonstrated that both mutations and recombination events could contribute to the genetic diversity of the Italian isolates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) causes a highly contagious disease in chickens and is one of the major problems of poultry industry in many countries. IBV is a prototype member of the Coronaviridae family, genus Coronavirus. Its genome is a single-stranded linear RNA molecule of 27.6 kb [1] that encodes four structural proteins, designated N, M, S and E [2, 3]. The spike glycoprotein S is post-translationally processed into S1 and S2 subunits, [4], the S1 contains virus neutralization, cell attachment and serotype specific epitopes [5–7]. Both S and N proteins are the major inductors of immune response against IBV infection [8, 9].

Many different serotypes of IBV have been identified throughout the world [10] and new variants emerge continuously in spite of vaccination programs [11–13]. Epizootological situation on IBV in Italy is not an exception. For the last three decades, at least 10 antigenically different isolates have been detected in Italy [14, 15]. While most of them had a transient appearance, some serotypes (e.g., Massachusetts [Mass] and AZ 23/74) have been isolated for a long period in many regions. Serological and molecular analysis of IBV field strains from Italy isolated in 1997 have shown the co-existence of four virus types (793/B, 624/I, B1648 and Mass) identified also in other European countries [16]. Partial S1 gene sequence analysis of 624/I strain, first detected in Italy in 1993 [17], confirmed that this virus was a novel IBV genotype. The results of the surveillance program undertaken lately in Italy have indicated the co-circulation of three types of IBV [18]. Using RT-PCR and partial sequencing of the S1 gene, 7 isolates were identified as of 793/B type, 2 isolates were closely related to previously undetected in Europe Chinese QXIBV strain, and the other 8 IBVs were of newly emerged Italy-02 genotype. Since this genotype is currently one of the dominant types of IBV in Western Europe [19] it has been recently characterized both antigenically and phylogenetically (S1 gene analysis) by the example of Spanish isolates and has been shown to be a new IBV serotype [20].

This novel genotype was named according to the isolate number 2 (Italy-02), S1 gene sequence of which we submitted to the EMBL database (accession number AJ457137) in 2002, however, we did not have information on its outspread and importance to poultry industry at that time and had not published our data yet. Since field situation has significantly changed for the last decade and only one of four IBV types (793/B), detected in 1997, has persisted recently together with two new types (Italy-02 and QXIBV), it was of interest to analyze when these variants could emerge. Our isolates were collected in 1999, i.e., in period between the two major studies on IBV in Italy described above. In the present study, we performed S1 and N gene molecular characterization of 10 Italian IBV isolates to establish the genetic spectrum, origin and evolution of IBVs circulated in Italy including novel Italy-02-type viruses.

Materials and methods

Viruses

The field viruses used in this study were obtained from the broiler flocks in Italy and isolated in 9–11-day-old SPF chicken embryos (Table 1). Allantoic fluid after the fifth serial passage was collected 48–72 h post inoculation, frozen at −80°C, and then tested for the presence of IBV genome using RT-PCR.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated from 50 μl of the sample using GF/F glass fiber filters as described previously [21, 22]. Briefly, the extraction procedure was as follows: 0.5 ml of 4 M guanidine isothiocyanate (Fluka) was added to 50 μl of the sample; the mixture was vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 15–20 min. Equal volume of 96% ethanol was added and the mixture was vortexed and then applied onto a GF/F filter placed into micro spin column. The solvent was removed by centrifugation (5–10 s) or vacuum filtration. Filter with the adsorbed RNA was washed twice with 0.7 ml of 80% ethanol, then column was placed into new tube and dried by centrifugation (13,000g) for 1–2 min. RNA was eluted with 50 μl of water, 3 μl were used for RT-PCR.

Continuous reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Continuous RT-PCR protocols for amplification of S1 variable region and complete S1 gene have been described previously [23, 24]. Positions of primers relative to the IBV genome are shown in Fig. 1. Sequences of the primers used for amplification of S1 gene variable region are as follows: forward primers are S7 (5′-tactactaccagagtgc(c/t)tt-3′) and S9 (5′-gatggttggcattt(a/g)ca(c/t)gg-3′), reverse primers are S5 (5′-gtgccattgacaaaataagc-3′), S6 (5′-acatc(t/a)tgtgcggtgccatt-3′) and S8 (5′-ctttataagttat(g/a)gg(t/g)ccacca-3′). First RT-PCR was done using primers S7–S6 (amplicon size is 572 base pairs, bp), secondary amplification (nested-PCR) was performed using nested primers S9–S5 (530 bp) or S9–S8 (487 bp). N gene fragment was amplified using primers IBVN1 (5′-acccttaccagcaaccc-3′) and IBVN2 (5′-gtcttgtcccgcgtgta-3′) designed by Zwaagstra et al. [25].

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis

PCR products were purified by Magic PCR Preps DNA Purification System procedure (Promega, USA) and sequenced directly using flanking primers and fmol DNA Cycle Sequencing System (Promega, USA) as described by the manufacturer. The sequences determined reflect the nucleotides that were possessed by the majority of the viral RNAs at each position due to possible heterogeneity of virus population. Each isolate was sequenced in both directions using forward and reverse primers in duplicate runs. Sequences having less than 99% reproducibility were not analyzed. Aligned sequences were then cropped to a length of 384 bp (S1 gene) and 300 bp (N gene) and then used for phylogenetic studies. Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis were performed using MegAlign program version 5.0 with Clustal W method (DNAStar Inc., Madison, WI, USA). The phylogenetic tree generated by MegAlign is a rooted tree, predicted from the multiple sequence alignment. The length of each pair of branches represent the distance between sequence pairs, while the units at the bottom of the tree indicate the number of substitution events.

Accession numbers of IBV sequences

S1 gene sequences of reference strains used for comparisons are as follows: M41 (M21883); H120 (M21970); H52 (AF352315); Conn (L18990); D274 (X15832); 4/91-att (AF093793); 624/I (AJ243261); B1648 (X87238); Ark99 (M99482); Gray (L18989); QXIBV (AF193423); CK/CH/LHB/96I (DQ167137); VicS (U29519); V18/91 (U29521).

N gene sequences used for comparisons have the following accession numbers: M41 (M28566); H120 (AY028296); H52 (AF352310); Conn (AY942746); 793/B (DQ294723); Ark99 (M85244); Gray (S48137); QXIBV (AF199412); CK/CH/LHB/96I (DQ287912); VicS (U52594); V18/91 (U52601). Partial N gene sequence of D274 strain is from Zwaagstra et al. [25].

Results and discussion

Ten IBV field strains were isolated in Central and Northern Italy in 1999 from broiler chickens and cockerels that experienced respiratory problems, swollen head syndrome or nephrosis–nephritis (Table 1). All of the flocks were vaccinated at one day of age with live vaccine of Mass serotype (H120 strain). As a part of cooperative study, samples of allantoic fluid containing these viruses, harvested after the fifth passage in SPF chicken embryos were delivered to the All-Russian Research Institute for Animal Health (Vladimir, Russia) for molecular characterization.

The isolates were tested in RT-PCR using primers targeting S1 gene variable region and more conserved 5′-terminal N gene region (Fig. 1). IBV S1 gene is used very often to assess the genetic diversity and evolution direction of IBV due to its high variability and sequence correlation with serological grouping [20, 26]. The phylogenetic analysis based on N gene sequences does not always follow the clustering based on S1 gene [25]. However, the comparison of N gene sequences coupled with S1, is also very useful tool for evolutionary analysis, allowing to find out recombinant viruses since regions between S1 and N genes are involved in recombination [27, 28]. The S1 primer set was used previously for testing field samples in Russia and was shown to detect a wide range of IBV genotypes [23]. cDNA amplicons of expected size were obtained with S9–S5 (isolates Italy-02; 04; 06 and 08) or with S9–S8 (isolates Italy-01, 05, 07, 09 and 10) primers. However, one isolate, Italy-03, demonstrated negative result by RT-PCR using all combinations of the S1 gene primers. Primers IBVN1 and IBVN2 successfully amplified cDNA in all samples and the resulting PCR product contained N gene sequence that was informative for the differentiation of all strains. These primers have been shown previously to amplify 18 IBV strains of different serotypes isolated in the USA, Europe and Japan [25].

Partial nucleotide sequences of S1 and N genes of the Italian isolates were initially compared with published IBV sequences using BLAST search within the EMBL/GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Reference IBV strains included in the final dendrograms and used for comparisons (Table 2) comprised viruses identified previously in Italy (M41, 793/B, 624/I, QXIBV and B1648) as well as IBVs from China, USA and Australia, however, their number was limited by availability of corresponding N gene sequences in databases.

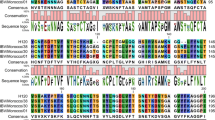

Nucleotide sequence alignments revealed many point mutations, short deletions and insertions in S1 gene region of Italian isolates, whereas the partial N gene sequences displayed only point mutations distributed rather evenly along the analyzed fragment. Major S1 gene sequence changes included insertions of 6 nucleotides (in all isolates in positions 350–351 and only in Italy-02-type isolates in position 420–421) and deletions of 3 nucleotides (in Italy-02 type isolates in position 185–187) compared to published IBV sequence of H120 vaccine strain.

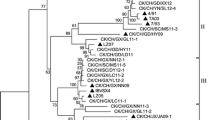

Our genetic grouping method based on IBV hypervariable region sequence in S1 [23], as well as similar methods from previous reports [26] have shown that variation in this region often, but not always, correlate with virus serotype and sometimes with geographic origin of strain. Phylogenetic tree constructed from the S1 gene sequences revealed several genetic groups including widespread Mass (M41), European 793/B, 624/I, Italy-02, D274 and B1648, North-American Ark99 and Gray, Chinese QXIBV and CK/CH/LHB/96I, Australian VicS and the most distant V18/91 (Fig. 2a). The analysis showed that the Italian isolates identified in this study fell into three distinct genotypes. Six isolates belonged to two genotypes that had circulated in Italy since 1990s [16, 17]; five of them were placed together with 793/B-type strains and one isolate had very close sequence relationship (94.6% nucleotide identity) with 624/I strain. No Massachusetts or B1648 type viruses were detected in contrast to 1997 data [16]. The other three isolates, Italy-02, 04 and 08, formed novel genotype detected recently in many countries of Western Europe [19, 29] including Italy [18], however, no sequence data on these late Italian IBVs is available in EMBL/GenBank database yet. For one of the variant viruses, Italy-02, which afterwards became the prototype strain, S1 gene was sequenced in its entirety and deposited to sequence database. Comparative S1 gene analysis of this strain and reference strains has been reported recently by others [20]. Four Spanish isolates of this type, that were identified as a new serotype and genotype, shared 96.6–98.0% S1 gene nucleotide identity with Italy-02 and not more than 84% with all of the other strains.

Phylogenetic relationships of Italian IBV isolates and selected reference strains based on the partial S1 gene sequences (a) comprising 166–549 bp (numbering corresponds to H120 vaccine strain [M21970]) and partial N gene sequences (b) comprising first 300 bp beginning from AUG start codon. The rooted trees were generated by MegAlign 5.00 program from the Clustal W multiple sequence alignment (DNAStar Inc., Madison, WI). IBV genotypes that Italian isolates belong to are designated by braces. Italian isolates are shown in bold type. Vaccine strain H120 is boxed

In contrast, phylogenetic analysis of N gene revealed lower sequence variability and different clustering (Fig. 2b). North-American and European strains and the majority of Italian isolates were placed in one group (I), two Italian viruses (Italy-02 and 10) clustered with 793/B strain (II); Chinese (III) and Australian strains (IV and V) were the most distant from the others. Italian viruses from the first group formed two mixed subgroups (Mass + 624/I + Italy-02 and 793/B + Italy-02) that consisted of representatives of different S1 genotypes. Thus, three variant IBVs of Italy-02 genotype, shared 96.7–99.2% S1 gene nucleotide identity with each other but belonged to three separate subgroups based on more conserved N gene sequences (89.7–93% identity). This could suggest that part of N gene from these isolates might have different origin, while very similar parts of S1 gene might evolve by recombination events, however, we do not know the parental N gene sequence for this genotype. Only one of the five 793/B-type isolates (Italy-10) clustered with the 793/B strain sharing 99.3% partial N gene identity, whereas the other four isolates were genetically distant from them (only 87.7–89.7% identity) and formed separate subgroup together with Italy-08 isolate. As with Italy-02-type viruses, Italy-10 and the other four 793/B-type Italian isolates might originate from different ancestors. Italy-03 and Italy-06 isolates shared high N gene identity, 99.3% and 97.7%, respectively, with vaccine strain H120. The former isolate was not detected by PCR with the S1 gene primers and, therefore, might have very divergent S1 sequence; the latter belonged to 624/I-type and had only 69.5% S1 sequence identity with H120. Since both viruses were isolated from chickens vaccinated with live Mass-type vaccine, this data might indicate the involvement of the H120 strain in generation of these two isolates, which could obtain their S1 sequences by recombination.

Unfortunately, N gene sequences of certain IBV strains that could be extremely useful for such evolutionary predictions are not available (624/I and B1648) or very limited (only one 793/B sequence), therefore we can consider recombination only as a probable mechanism of evolution for some Italian IBVs.

In summary, our analysis showed that the genetic spectrum of IBV field strains has changed rapidly for rather short period. Thus, only two of the four genotypes, 793/B and 624/I, identified in Italy in 1997 [16], had persisted 2 years later, and only 793/B type has still circulated among the poultry flocks now [18]. Chinese strain QXIBV was not detected previously and during our studies, therefore it might be introduced into Italy later [18]. Interestingly, this IBV type has been recently detected in Russia [23] and Poland [30] and, therefore, might have widespread outside China. Novel genotype Italy-02, which we first detected in Italy in 1999, has become the prevalent IBV type in the country in 2004–2005 [18].

IBV, as well as some other RNA viruses, can mutate very rapidly involving different mechanisms that result in extensive antigenic variation. IBV population is considered to be in a state of continuous flux with appearance of new drifts and shifts in their genome [15]. Several factors determine IBV evolution including general factors such as inherent high mutability of RNA genome due to the absence of proof-reading mechanisms during replication, and more specific for IBV, namely, widespread use of live vaccines, immunological pressure caused by immune bird population, frequent mixed infections, the ability to replicate in very many tissues [15, 31, 32].

Recombination is one of the important IBV evolution mechanisms which together with spontaneous mutations could result in very rapid genetic changes generating new variant strains in the field [33, 34]. Thus, phylogenetic analysis of the S1 gene has suggested that the Italy-02 genotype has a mosaic sequence (5′ region shared maximum similarity with D274 and 3′ region with 4/91 strains) and it has undergone a recombination event [20]. Our S1 gene analysis of three Italian isolates of this type confirmed the high 5′ region nucleotide identity with D274, while N gene analysis displayed indication of potential intergenic recombination. Phylogenetic analysis of S1 and N gene sequences of IBVs from Japan, Taiwan and Korea revealed that recombination has occurred frequently between field strains [27, 35]. Thus, three Japanese strains might all be recombinant viruses derived from Australian and North American IBVs. The phylogenetic trees constructed from the S1 and N genes have indicated recombination in other two field isolates from Taiwan [28]. Sequence analysis of Australian strains of new N4/02 type has shown high N gene similarity with previously detected subgroup 1 viruses and very low level of S1 gene identity with them [31]. Our data has provided the evidence that both genome mutations and intergenic recombination events could have taken place in the evolution of the Italian IBV isolates of different genotypes.

References

M.E. Boursnell, T.D. Brown, I.J. Foulds, P.F. Green, F.M. Tomley, M.M. Binns, J. Gen. Virol. 68, 57–77 (1987)

D. Cavanagh, J. Gen. Virol. 53, 93–103 (1981)

S. Sutou, S. Sato, T. Okabe, M. Nakai, N. Sasaki, Virology 165, 589–595 (1988)

D. Cavanagh, P.J. Davis, D.J. Pappin, M.M. Binns, M.E. Boursnell, T.D. Brown, Virus Res. 4, 133–143 (1986)

A.P. Mockett, D. Cavanagh, T.D. Brown, J. Gen. Virol. 65, 2281–2286 (1984)

G. Koch, L. Hartog, A. Kant, D.J. van Roozelaar, J. Gen. Virol. 71, 1929–1935 (1990)

R. Casais, B. Dove, D. Cavanagh, P. Britton, J. Virol. 77, 9084–9089 (2003)

J. Ignjatovic, L. Galli, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 342, 449–453 (1993)

J. Ignjatovic, S. Sapats, Arch. Virol. 150, 1813–1831 (2005)

J. Ignjatovic, S. Sapats, Rev. Sci. Tech. 19, 493–508 (2000)

J.K. Cook, S.J. Orbell, M.A. Woods, M.B. Huggins, Vet. Rec. 138, 178–180 (1996)

S. Liu, X. Kong, Avian Pathol. 33, 321–327 (2004)

M. Mase, K. Tsukamoto, K. Imai, S. Yamaguchi, Arch. Virol. 149, 2069–2078 (2004)

A. Zanella, R. Coaro, G. Fabris, R. Marchi, A. Lavazza, Vet. Rec. 146, 191–193 (2000)

A. Zanella, A. Lavazza, R. Marchi, A. Moreno Martin, F. Paganelli, Avian Dis. 47, 180–185 (2003)

I. Capua, Z. Minta, E. Karpinska, K. Mawditt, P. Britton, D. Cavanagh, R. Gough, Avian Pathol. 28, 587–592 (1999)

I. Capua, R.E. Gough, M. Mancini, C. Casaccia, C. Weiss, Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B 41, 83–89 (1994)

M.S. Beato, C. De Battisti, C. Terregino, A. Drago, I. Capua, G. Ortali, Vet. Rec. 156, 720 (2005)

R.C. Jones, K.J. Worthington, R.E. Gough, Vet. Rec. 156, 260 (2005)

R. Dolz, J. Pujols, G. Ordonez, R. Porta, N. Majo, Avian Pathol. 35, 77–85 (2006)

O.G. Gribanov, A.V. Shcherbakov, N.A. Perevozchikova, V.V. Drygin, A.A. Gusev, Bioorg. Khim. 23, 763–765 (1997)

N.N. Lougovskaia, A.A. Lougovskoi, Y.A. Bochkov, G.V. Batchenko, N.S. Mudrak, V.V. Drygin, A.V. Borisov, V.V. Borisov, A.A. Gusev, Avian Pathol. 31, 549–557 (2002)

Y.A. Bochkov, G.V. Batchenko, L.O. Shcherbakova, A.V. Borisov, V.V. Drygin, Avian Pathol. 35, 379–393 (2006)

F. Mallet, G. Oriol, C. Mary, B. Verrier, B. Mandrand, Biotechniques 18, 678–687 (1995)

K.A. Zwaagstra, B.A. van der Zeijst, J.G. Kusters, J. Clin. Microbiol. 30, 79–84 (1992)

C.H. Wang, Y.C. Huang, Arch. Virol. 145, 291–300 (2000)

H.K. Shieh, J.H. Shien, H.Y. Chou, Y. Shimizu, J.N. Chen, P.C. Chang, J. Vet. Med. Sci. 66, 555–558 (2004)

Y.P. Huang, H.C. Lee, M.C. Cheng, C.H. Wang, Avian Dis. 48, 581–589 (2004)

K.J. Worthington, C. Savage, C.J. Naylor, W. Wijmenga, R.C. Jones, in IV International Symposium on Avian Corona- and Pneumovirus Infections, Rauischholzhausen, Germany, 125–133 (2004)

K. Domanska-Blicharz, Z. Minta, K. Smietanka, T. Porwan, Vet. Rec. 158, 808 (2006)

J. Ignjatovic, G. Gould, S. Sapats, Arch. Virol. 151, 1567–1585 (2006)

D. Cavanagh, J.P. Picault, R. Gough, M. Hess, K. Mawditt, P. Britton, Avian Pathol. 34, 20–25 (2005)

L. Wang, D. Junker, E.W. Collisson, Virology 192, 710–716 (1993)

C.W. Lee, M.W. Jackwood, Arch. Virol. 145, 2135–2148 (2000)

J.Y. Park, S.I. Pak, H.W. Sung, J.H. Kim, C.S. Song, C.W. Lee, H.M. Kwon, Virus Genes 31, 153–162 (2005)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Galina Batchenko for her excellent assistance with virus propagation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The nucleotide sequences reported in this paper have been submitted to the EMBL/GenBank database and have been assigned the accession numbers AJ458958, AJ457137, AJ458959, AJ491327, AJ458960–AJ458964 for the S1 gene and AM260961–AM260970 for the N gene.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bochkov, Y., Tosi, G., Massi, P. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of partial S1 and N gene sequences of infectious bronchitis virus isolates from Italy revealed genetic diversity and recombination. Virus Genes 35, 65–71 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-006-0037-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-006-0037-0