Abstract

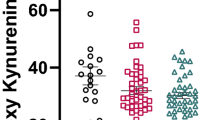

Evidence suggests that activation of the tryptophan catabolite (TRYCAT) pathway is involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. However, no previous study examined whether TRYCAT pathway activation is associated with deficit schizophrenia. We measured IgA responses to TRYCATs, namely quinolinic acid, picolinic acid, kynurenic acid, xanthurenic acid, and anthranilic acid and 3-OH-kynurenine, in 40 healthy controls and in schizophrenic patients with (n = 40) and without (n = 40) deficit, defined according to the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS). Primary deficit schizophrenia is accompanied by an activated TRYCAT pathway as compared to controls and nondeficit schizophrenia. Participants with deficit schizophrenia show increased IgA responses to xanthurenic acid, picolinic acid, and quinolinic acid and relatively lowered IgA responses to kynurenic and anthranilic acids, as compared to patients with nondeficit schizophrenia. Both schizophrenia subgroups show increased IgA responses to 3-OH-kynurenine as compared to controls. The IgA responses to noxious TRYCATs, namely xanthurenic acid, picolinic acid, quinolinic acid, and 3-OH-kynurenine, but not protective TRYCATS, namely anthranilic acid and kunyrenic acid, are significantly higher in deficit schizophrenia than in controls. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia are significantly and positively associated with increased IgA responses directed against picolinic acid and inversely with anthranilic acid, whereas no significant associations between positive symptoms and IgA responses to TRYCATs were found. In conclusion, primary deficit schizophrenia is characterized by TRYCAT pathway activation and differs from nondeficit schizophrenia by a highly specific TRYCAT pattern suggesting increased excitotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and neurotoxicity, as well as inflammation and oxidative stress. The specific alterations in IgA responses to TRYCATs provide further insight for the biological delineation of deficit versus nondeficit schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Smith RS, Maes M (1995) The macrophage-T-lymphocyte theory of schizophrenia: additional evidence. Med Hypotheses 45:135–141

Anderson G, Maes M (2013) Schizophrenia: linking prenatal infection to cytokines, the tryptophan catabolite (TRYCAT) pathway, NMDA receptor hypofunction, neurodevelopment and neuroprogression. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 42:5–19

Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, Maes M, Berk M (2014) Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 48:512–529

Davis J, Eyre H, Jacka FN, Dodd S, Dean O, McEwen S, Debnath M, McGrath J (2016) A review of vulnerability and risks for schizophrenia: beyond the two hit hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 65:185–194

Noto C, Ota VK, Santoro ML, Ortiz BB, Rizzo LB, Higuchi CH, Cordeiro Q, Belangero SI (2015) Effects of depression on the cytokine profile in drug naïve first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 164:53–58

Noto C, Ota VK, Santoro ML, Gouvea ES, Silva PN, Spindola LM, Cordeiro Q, Bressan RA (2015) Depression, cytokine, and cytokine by treatment interactions modulate gene expression in antipsychotic naïve first episode psychosis. Mol Neurobiol

Noto C, Maes M, Ota VK, Teixeira AL, Bressan RA, Gadelha A, Brietzke E (2015) High predictive value of immune-inflammatory biomarkers for schizophrenia diagnosis and association with treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry 27:1–8

Upthegrove R, Manzanares-Teson N, Barnes NM (2014) Cytokine function in medication-naive first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 155:101–108

Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ (2016) A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. doi:10.1038/mp.2016.3

Maes M, Meltzer HY, Bosmans E (1994) Immune-inflammatory markers in schizophrenia: comparison to normal controls and effects of clozapine. Acta Psychiatr Scand 89:346–351

Maes M, Meltzer HY, Buckley P, Bosmans E (1995) Plasma-soluble interleukin-2 and transferrin receptor in schizophrenia and major depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 244:325–329

Noto C, Ota VK, Gadelha A, Noto MN, Barbosa DS, Bonifácio KL, Nunes SO, Cordeiro Q (2015) Oxidative stress in drug naïve first episode psychosis and antioxidant effects of risperidone. J Psychiatr Res 68:210–216

Severance EG, Prandovszky E, Castiglione J, Yolken RH (2015) Gastroenterology issues in schizophrenia: why the gut matters. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17(5):27

Alexander KS, Wu HQ, Schwarcz R, Bruno JP (2012) Acute elevations of brain kynurenic acid impair cognitive flexibility: normalization by the alpha7 positive modulator galantamine. Psychopharmacology 220:627–637

Anderson G, Ojala J (2010) Alzheimer’s and seizures: interleukin-18, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and quinolinic acid. Int J Tryptophan Res 3:169–173

Bosco MC, Rapisarda A, Massazza S, Melillo G, Young H, Varesio L (2000) The tryptophan catabolite picolinic acid selectively induces the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha and −1 beta in macrophages. J Immunol 164:3283–3291

Guillemin GJ, Cullen KM, Lim CK, Smythe GA, Garner B, Kapoor V, Takikawa O, Brew BJ (2007) Characterization of the kynurenine pathway in human neurons. J Neurosci 27:12884–12892

Darlington LG, Forrest CM, Mackay GM, Smith RA, Smith AJ, Stoy N, Stone TW (2010) On the biological importance of the 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid: anthranilic acid ratio. Int J Tryptophan Res 3:51–59

Gobaille S, Kemmel V, Brumaru D, Dugave C, Aunis D, Maitre M (2008) Xanthurenic acid distribution, transport, accumulation and release in the rat brain. J Neurochem 105:982–993

Taleb O, Maammar M, Brumaru D, Bourguignon JJ, Schmitt M, Klein C, Kemmel V, Maitre M (2012) Xanthurenic acid binds to neuronal G-protein-coupled receptors that secondarily activate cationic channels in the cell line NCB-20. PLoS One 7:e48553

Lee M, Jayathilake K, Dai J, Meltzer HY (2011) Decreased plasma tryptophan and tryptophan/large neutral amino acid ratio in patients with neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: relationship to plasma cortisol concentration. Psychiatry Res 185:328–333

Barry S, Clarke G, Scully P, Dinan TG (2009) Kynurenine pathway in psychosis: evidence of increased tryptophan degradation. J Psychopharmacol 23:287–294

Krause D, Weidinger E, Dippel C, Riedel M, Schwarz MJ, Müller N, Myint AM (2013) Impact of different antipsychotics on cytokines and tryptophan metabolites in stimulated cultures from patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Danub 25:389–397

Linderholm KR, Skogh E, Olsson SK, Dahl ML, Holtze M, Engberg G, Samuelsson M, Erhardt S (2012) Increased levels of kynurenine and kynurenic acid in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 38:426–432

Schwarcz R, Rassoulpour A, Wu HQ, Medoff D, Tamminga CA, Roberts RC (2001) Increased cortical kynurenate content in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 50:521–530

Miller CL, Llenos IC, Dulay JR, Barillo MM, Yolken RH, Weis S (2004) Expression of the kynurenine pathway enzyme tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase is increased in the frontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis 15:618–629

Oxenkrug G, van der Hart M, Roeser J, Summergrad P (2016) Anthranilic acid: a potential biomarker and treatment target for schizophrenia. Ann Psychiatry Ment Health 4

Fazio F, Lionetto L, Curto M, Iacovelli L, Cavallari M, Zappulla C, Ulivieri M, Napoletano F (2015) Xanthurenic acid activates mGlu2/3 metabotropic glutamate receptors and is a potential trait marker for schizophrenia. Sci Rep 5:17799

Koola MM (2016) Kynurenine pathway and cognitive impairments in schizophrenia: pharmacogenetics of galantamine and memantine. Schizophr Res Cogn 4:4–9

Erhardt S, Schwieler L, Imbeault S, Engberg G (2016) The kynurenine pathway in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropharmacology

Okusaga O, Fuchs D, Reeves G, Giegling I, Hartmann AM, Konte B, Friedl M, Groer M (2016) Kynurenine and tryptophan levels in patients with schizophrenia with elevated antigliadin immunoglobulin G antibodies. Psychosom Med

Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, Andreasen NC (2005) Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 162:495–506

Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Swartz M, Stroup S, Lieberman JA, Keefe RS (2008) Relationship of cognition and psychopathology to functional impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 165:978–987

Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AM (1988) Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry 145:578–583

Kirkpatrick B, Galderisi S (2008) Deficit schizophrenia: an update. World Psychiatry 7:143–147

Cohen AS, Docherty NM (2004) Deficit versus negative syndrome in schizophrenia: prediction of attentional impairment. Schizophr Bull 30:827–835

Fervaha G, Agid O, Foussias G, Siddiqui I, Takeuchi H, Remington G (2016) Neurocognitive impairment in the deficit subtype of schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 266:397–407

Roomruangwong C, Kanchanatawan B, Carvalho AF, Sirivichayakul S, Duleu S, Geffard M, Maes M (2016) Body image dissatisfaction in pregnant and non-pregnant females is strongly predicted by immune activation and mucosa-derived activation of the tryptophan catabolite (TRYCAT) pathway. World J Biol Psychiatry 30:1–10

Roomruangwong C, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Anderson G, Carvalho AF, Duleu S, Geffard M, Maes M (2016) IgA/IgM responses to tryptophan and tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs) are differently associated with prenatal depression, physio-somatic symptoms at the end of term and premenstrual syndrome. Mol Neurobiol

Onodera T, Jang MH, Guo Z, Yamasaki M, Hirata T, Bai Z, Tsuji NM, Nagakubo D (2009) Constitutive expression of IDO by dendritic cells of mesenteric lymph nodes: functional involvement of the CTLA-4/B7 and CCL22/CCR4 interactions. J Immunol 183:5608–5614

Cherayil BJ (2009) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in intestinal immunity and inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 15:1391–1396

Kittirathanapaiboon P, Khamwongpin M (2005) The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) Thai version: Suanprung Hospital, Department of Mental Health

Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, McKenney PD, Alphs LD, Carpenter WT Jr (1989) The Schedule for the Deficit syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 30:119–123

Andreasen NC (1989) The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 7:49–58

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1986) Negative Symptom Rating Scale: limitations in psychometric and research methodology. Psychiatry Res 19:169–173

Overall JE, Gorham DR (1962) The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep 10:799–812

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO (1991) The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 86:1119–1127

Duleu S, Mangas A, Sevin F, Veyret B, Bessede A, Geffard M (2010) Circulating Antibodies to IDO/THO Pathway Metabolites in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 15

Roomruangwong C, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Anderson G, Carvalho AF, Duleu S, Geffard M, Maes M (2016) IgA / IgM responses to Gram-negative bacteria are not associated with prenatal depression, but with physio-somatic symptoms and activation of the tryptophan catabolite pathway at the end of term and postnatal anxiety. CNS Neurological Disorders – Drug Targets

Kita T, Morrison PF, Heyes MP, Markey SP (2002) Effects of systemic and central nervous system localized inflammation on the contributions of metabolic precursors to the L-kynurenine and quinolinic acid pools in brain. J Neurochem 82:258–268

Anderson G, Maes M (2015) The gut-brain Axis: the role of melatonin in linking psychiatric, inflammatory and neurodegenerative conditions. Adv Integrative Med 2:31–37

Sathyasaikumar KV, Stachowski EK, Wonodi I, Roberts RC, Rassoulpour A, McMahon RP, Schwarcz R (2011) Impaired kynurenine pathway metabolism in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 37:1147–1156

Lim CK, Brew BJ, Sundaram G, Guillemin GJ (2010) Understanding the roles of the kynurenine pathway in multiple sclerosis progression. Int J Tryptophan Res 3:157–167

Grant RS, Coggan SE, Smythe GA (2009) The physiological action of picolinic acid in the human brain. Int J Tryptophan Res 2:71–79

Dove S (2004) Picolinic acids as inhibitors of dopamine beta-monooxygenase: QSAR and putative binding site. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 337:645–653

Maes M, Mihaylova I, Ruyter MD, Kubera M, Bosmans E (2007) The immune effects of TRYCATs (tryptophan catabolites along the IDO pathway): relevance for depression—and other conditions characterized by tryptophan depletion induced by inflammation. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 28:826–831

Lugo-Huitrón R, Blanco-Ayala T, Ugalde-Muñiz P, Carrillo-Mora P, Pedraza-Chaverrí J, Silva-Adaya D, Maldonado PD, Torres I (2011) On the antioxidant properties of kynurenic acid: free radical scavenging activity and inhibition of oxidative stress. Neurotoxicol Teratol 33:538–547

Rio GF, Silva BV, Martinez ST, Pinto AC (2015) Anthranilic acids from isatin: an efficient, versatile and environmentally friendly method. An Acad Bras Cienc 87:1525–1529

Amori L, Wu HQ, Marinozzi M, Pellicciari R, Guidetti P, Schwarcz R (2009) Specific inhibition of kynurenate synthesis enhances extracellular dopamine levels in the rodent striatum. Neuroscience 159:196–203

Rassoulpour A, Wu HQ, Ferre S, Schwarcz R (2005) Nanomolar concentrations of kynurenic acid reduce extracellular dopamine levels in the striatum. J Neurochem 93:762–765

Yu P, Di Prospero NA, Sapko MT, Cai T, Chen A, Melendez-Ferro M, Du F, Whetsell WO Jr (2004) Biochemical and phenotypic abnormalities in kynurenine aminotransferase II-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol 24:6919–6930

Behan WM, Stone TW (2002) Enhanced neuronal damage by co-administration of quinolinic acid and free radicals, and protection by adenosine A2A receptor antagonists. Br J Pharmacol 135:1435–1442

Guidetti P, Schwarcz R (2003) 3-Hydroxykynurenine and quinolinate: pathogenic synergism in early grade Huntington’s disease? Adv Exp Med Biol 527:137–145

Neale SA, Copeland CS, Uebele VN, Thomson FJ, Salt TE (2013) Modulation of hippocampal synaptic transmission by the kynurenine pathway member xanthurenic acid and other VGLUT inhibitors. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:1060–1067

Marek GJ, Wright RA, Schoepp DD, Monn JA, Aghajanian GK (2000) Physiological antagonism between 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) and group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in prefrontal cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 292:76–87

Beninger RJ, Colton AM, Ingles JL, Jhamandas K, Boegman RJ (1994) Picolinic acid blocks the neurotoxic but not the neuroexcitant properties of quinolinic acid in the rat brain: evidence from turning behaviour and tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry. Neuroscience 61:603–612

Anderson G, Maes M, Berk M (2013) Schizophrenia is primed for an increased expression of depression through activation of immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and tryptophan catabolite pathways. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 42:101–114

Feigenson KA, Kusnecov AW, Silverstein SM (2014) Inflammation and the two-hit hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 38(72–93):006

Morris G, Carvalho AF, Anderson G, Galecki P, Maes M (2016) The many neuroprogressive actions of tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs) that may be associated with the pathophysiology of Neuro-immune disorders. Curr Pharm Des 22:963–977

Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Ruxrungtham K, Carvalho AF, Geffard M, Anderson G, Maes M(2017) Deficit schizophrenia is characterized by defects in IgM-mediated responses to noxious tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs): a paradigm shift toward defects in natural self-regulatory immune responses coupled with mucosa-derived TRYCAT pathway activation. Mol Neurobiol

Maes M, Berk M, Goehler L, Song C, Anderson G, Gałecki P, Leonard B (2012) Depression and sickness behavior are Janus-faced responses to shared inflammatory pathways. BMC Med 29(10):66

da Silva Araújo T, Maia Chaves Filho AJ, Monte AS, Isabelle de Góis Queiroz A, Cordeiro RC, de Jesus Souza Machado M, de Freitas Lima R, Freitas de Lucena D (2017) Reversal of schizophrenia-like symptoms and immune alterations in mice by immunomodulatory drugs. J Psychiatr Res 84:49–58

Maes M, Leonard BE, Myint AM, Kubera M, Verkerk R (2011) The new ‘5-HT’ hypothesis of depression: cell-mediated immune activation induces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which leads to lower plasma tryptophan and an increased synthesis of detrimental tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs), both of which contribute to the onset of depression. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 35:702–721

Marttila S, Jylhävä J, Eklund C, Hervonen A, Jylhä M, Hurme M (2011) Aging-associated increase in indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity appears to be unrelated to the transcription of the IDO1 or IDO2 genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immun Ageing 8:9

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Asahi Glass Foundation, Chulalongkorn University Centenary Academic Development Project, and IDRPHT and Gemac, France.

Author’s Contributions

All the contributing authors have participated in the manuscript. MM and BK designed the study. BK recruited patients and completed diagnostic interviews and rating scales measurements. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. MM carried out the statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was conducted according to Thai and international ethics and privacy laws. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, which is in compliance with the International Guideline for Human Research protection as required by the Declaration of Helsinki, The Belmont Report, CIOMS Guideline, and International Conference on Harmonization in Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanchanatawan, B., Sirivichayakul, S., Ruxrungtham, K. et al. Deficit, but Not Nondeficit, Schizophrenia Is Characterized by Mucosa-Associated Activation of the Tryptophan Catabolite (TRYCAT) Pathway with Highly Specific Increases in IgA Responses Directed to Picolinic, Xanthurenic, and Quinolinic Acid. Mol Neurobiol 55, 1524–1536 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-017-0417-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-017-0417-6