Abstract

Fortaleza is the fifth largest city of Brazil, and has become the most violent state capital in the last years. In this paper, we investigate whether violent crime rates are associated with the local development of the city. Using an unexplored data source about georeferenced murders and deaths due to bodily injury and theft, we show that violent crime rates exhibit a positive spatial dependence across clusters of census tracts. In other words, small urban areas with high (low) violent crime rates have neighbors, on average, with similar pattern of violent crime rates. Investigating the relationship between violent crime rates and variables associated with local development, spatial regressions suggest that high violent crime rates are related with low-income neighborhood, with high spatial isolation of poor households, low access to urban infrastructure, and high prevalence of illiterate adolescents and young black males. The study also provides important evidence about spillover effects that helps to understand how the absence of local development can expose neighbors to violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Forum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública produces its annual report with the main statistics about public safety in Brazil. According to these reports, the total number of deaths due to murders, bodily injury and theft are the following: 44,518 (2009), 43,272 (2010), 48,084 (2011), 53,054 (2012), 51,063 (2013), 57,091 (2014), and 55,574 (2015). These statistics at state level can be found in: http://www.forumseguranca.org.br/.

The number of deaths caused by violence in Fortaleza was 1989 in 2014, which means a rate per 100,000 inhabitants of 77.3. In São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, violence caused, respectively, 1360 and 1305 deaths in the same year, but they exhibit much smaller violent crime rates (11.4 and 20.2) (FBSP 2015).

In Economics, an individual’s decision of engaging in criminal activities is a function of the expected costs and benefits in comparison to what could be obtained in the labor market (Becker 1968; Stigler 1970). Such decision making process takes into account the chance of being apprehended, costs associated with the crime execution, the expected punishment, as well as the income from legitimate activities (Freeman 1999; Fajnzylber et al. 2002a,b).

For instance, Mimmi and Ecer (2010) show evidence that illegal connections and energy thefts are mostly explained as the urban slum dwellers’ response to non-affordable prices of electricity in Belo Horizonte, state capital of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

The quality of data coverage of the Brazilian Demographic Census has improved substantially since the 1970s. One of the biggest improvements of the 2010 Brazilian Census is the incorporation of new methodologies and technologies. For instance, the use of handheld devices in the 2010 Census and Post Enumeration Survey (PES) allowed improvement of quality and timeliness in the data collection process, and facilitated automatic matching of PES to the Census. The enumeration process was conducted in urban and rural areas, except in campsites, military bases, ships, boats, indigenous areas; and institutions such as penitentiary institutions, asylums, orphanages, convents and hospitals. Coverage rates were estimated for occupied private housing units and people living there (da Silva et al. 2015).

This evidence corroborates the literature which argues that large cities concentrate criminal activity and violence (Glaeser and Sacerdote 1999).

The colors comprise the following intervals of violent crime rates (VCRs): dark green includes HDUs with VCRs between 0 and 35 per 100,000 inhabitants; light green includes HDUs with VCRs between 36 and 58 per 100,000 inhabitants; orange includes HDUs with VCRs between 59 and 98 per 100,000 inhabitants; red includes HDUs with VCRs equal to 99 per 100,000 inhabitants or more.

For further details, see de Castro (2014).

Census data on socioeconomic/demographic characteristics and urban infrastructure at the level of census tract can be accessed in the following link: http://downloads.ibge.gov.br/downloads_estatisticas.htm.

Spatial isolation, or residential segregation, is the degree of which two or more groups live separately from one another, in different parts of urban environment (Massey and Denton 1988). Groups themselves may be defined on the basis of any socially meaningful trait (e.g. race, ethnicity, income, education, or age) and segregation may occur at a variety of geographic levels (e.g. state, county, municipality, neighborhood, or block) (Massey et al. 2009).

A poor household is any particular domicile without monthly income or with per capita monthly income smaller than 1/2 nominal minimum wage in 2010 (minimum wage in 2010 reached R$ 510, or US$ PPP 318,00).

Poor households are said to be segregated if they are unevenly distributed over the census tract of a HDU. Isolation is minimized when all census tracts have the same relative number of poor and non-poor households as the HDU as a whole. Conversely, it is maximized when poor households and non-poor do not share the same census tract of residence. Kang (2015) used the dissimilarity index of poverty as a proxy for economic segregation.

Menezes et al. (2013), on the other hand, estimate spatial regressions at level of urban districts of Recife, Pernambuco, and find a positive and significant association between homicide rate and Gini index.

For instance, Helsley and Strange (1999) find that gated communities increases the opportunity cost of crime in the locality, but it may divert crimes to neighboring areas.

References

Alkimim, A., Clarke, K., & Oliveira, F. (2013). Fear, crime, and space: The case of Viçosa, Brazil. Applied Geography, 42, 124–132.

Anselin, L. (1988). Spatial econometrics: Methods and models. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bailey, W. (1984). Poverty, inequality, and city homicide rates. Criminology, 22(4), 531–550.

Becker, G. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217.

Blau, J., & Blau, P. (1982). The cost of inequality: Metropolitan structure and violent crime. American Sociological Review, 47, 114–129.

Bourguignon, F. (1999). Crime, violence, and inequitable development. Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics.

Carvalho, J. R., & Lavor, S. (2009). Repeat property criminal victimization and income inequality in Brazil. Revista EconomiA, 9(4), 87–110.

Carvalho, A., Cerqueira, D., & Lobão, W. (2005). Socioeconomic structure, self-fulfilment, homicides and spatial dependence in Brazil. In Texto para Discussão 1105. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA.

Chiu, W. H., & Madden, P. (1998). Burglary and income inequality. Journal of Public Economics, 69, 123–141.

Cook, P. J. (1986). The demand and supply of criminal opportunities. Crime and Justice, 7, 1–27.

Corvalan, A., & Vargas, M. (2015). Segregation and conflict: An empirical analysis. Journal of Development Economics, 116, 212–222.

Cutler, D., & Glaeser, E. (1997). Are ghettos good or bad? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(3), 827–872.

Da Silva, A. D., de Freitas, M. P. S., & Pessoa, D. G. C. (2015). Assessing coverage of the 2010 Brazilian census. Statistical Journal of the IAOS, 31, 215–225.

de Castro, B. (2014). Gangues impõem lei em 16 bairros. Jornal O Povo. Link: http://www.opovo.com.br/app/opovo/cotidiano/2014/02/10/noticiasjornalcotidiano,3204291/gangues-impoem-lei-em-16-bairros.shtml.

de Melo, S., Matias, L., & Andresen, M. (2015). Crime concentrations and similarities in spatial crime patterns in a Brazilian context. Applied Geography, 62, 314–324.

Ehrlich, I. (1973). Participation in illegitimate activities: A theoretical and empirical investigation. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 521–565.

Elhorst, J. P. (2014). Spatial econometrics: From cross-sectional data to spatial panels. Berlin: Springer.

Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Loayza, N. (2002). What causes violent crime? European Economic Review, 46, 1323–1357.

Fanjzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Loayza, N. (2002). Inequality and violent crime. Journal of Low & Economics, XLV, 1–40.

Faria, J., Ogura, L., & Sachsida, A. (2013). Crime in a planned city: The case of Brasília. Cities, 32, 80–87.

FBSP. (2015). Anuário brasileiro de segurança pública 2015. São Paulo: Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública.

Freeman, R. (1999). The economics of crime. In O. Ashenfelter and D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (vol. 3, chap. 52, pp. 3529–3571). Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V.

Gaviria, A., & Pagés, C. (2002). Patterns of crime victimization in Latin American cities. Journal of Development Economics, 67, 181–203.

Glaeser, E., & Sacerdote, B. (1999). Why is there more crime in cities? Journal of Political Economy, 107(6), S225–S258.

Glebbeek, M.-L., & Koonings, K. (2015). Between morro and asfalto. Violence, insecurity and socio-spatial segregation in Latin American cities. Habitat International, v54(1), 3–9.

Goldberg, M., Kim, K., & Ariano, M. (2014). How firms cope with crime and violence. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Helsley, R., & Strange, W. (1999). Gated communities and the economic geography of crime. Journal of Urban Economics, 46, 80–105.

Hicks, D., & Hicks, J. (2014). Jealous of the joneses: Conspicuous consumption, inequality, and crime. Oxford Economic Papers, 66(4), 1090–1120.

IBGE. (2011). Base de informações do censo demográfico 2010: Resultados do universo por setor censitário. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The life and death of great American cities. New York: Random House.

Justus, M., Kahn, T., & Kawamura, H. (2015). Relationship between income and repeat criminal victimization in Brazil. Revista EconomiA, 16(3), 295–309.

Kain, J. (1968). Housing segregation, negro employment and metropolitan decentralization. Quarterly Journal of Economics, LXXXI, 175–197.

Kang, S. (2015). Inequality and crime revisited: Effects of local inequality and economic segregation on crime. Journal of Population Economics, 29(2), 593–626.

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B., & Wilkinson, R. (1999). Crime: Social disorganization and relative deprivation. Social Science & Medicine, 48, 719–731.

Kelly, M. (2000). Inequality and crime. Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(4), 530–539.

Kennedy, B., Kawachi, I., Prothrow-Stith, D., Lochner, K., & Gupta, V. (1998). Social capital, income inequality, and firearm violent crime. Social Science & Medicine, 47(1), 7–17.

Krivo, L., & Peterson, R. (1996). Extremely disadvantage neighborhood and urban crime. Social Forces, 75(2), 619–650.

LeSage, J., & Pace, R. (2009). Introduction to spatial econometrics. United States: CRC Press.

Massey, D., & Denton, N. (1988). The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces, 67(2), 281–315.

Massey, D., Rothwell, J., & Domina, T. (2009). The changing bases of segregation in the United States. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 626, 74–90.

Menezes, T., Silveira-Neto, R., Monteiro, C., & Ratton, J. (2013). Spatial correlation between homicide rates and inequality: Evidence from urban neighborhoods. Economic Letters, 120, 97–99.

Merton, R. (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York: Free Press.

Messner, S., Raffalovich, L., & Shrock, P. (2002). Reassessing the cross-national relationship between income inequality and homicide rates: Implications of data quality control in the measurement of income distribution. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18(4), 377–395.

Mimmi, L., & Ecer, S. (2010). An econometric study of illegal electricity connections in the urban favelas of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Energy Policy, 38, 5081–5097.

Murray, J., Cerqueira, D., & Kahn, T. (2013). Crime and violence in Brazil: Systematic review of time trends, prevalence rates and risk factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(5), 471–483.

Pereira, D., Mota, C., & Andresen, M. (2015). Social disorganization and homicide in Recife, Brazil. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15623282.

Quillian, L. (2012). Segregation and poverty concentration: The role of three segregations. American Sociological Review, 77(1), 354–379.

Sampson, R. J. (1986). The social ecology of crime. Chap. Neighbourhood family structure and the risk of personal victimization, pp. 26–46. Springer-Verlag.

Sampson, R., & Groves, W. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social- disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 774–802.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press.

Skaperda, S., Soares, R., William, A., & Miller, S. (2009). The costs of violence. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Soares, R. (2004). Development, crime and punishment: Accounting for the international differences in crime rates. Journal of Development Economics, 73, 155–184.

South, S. J., & Messner, S. F. (2000). Crime and demography: Multiple linkages, reciprocal relations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 83–106.

Stigler, G. (1970). The optimum enforcement of Laws. Journal of Political Economy, 78(3), 526–536.

Taniguchi, T., Ratcliffe, J., & Taylor, R. (2011). Gang set space, drug markets, and crime around drug corners in Camden. Journal of Research Crime & Delinquency, 48(3), 327–363.

Tita, G., & Cohen, J. (2004). Measuring spatial diffusion of shots fired activity across city neighborhoods. In Spatially integrated social science (pp. 171–204). New York: Oxford Press.

Tita, G., & Radil, S. (2010). Making space for theory: The challenges of theorizing space and place for spatial analysis in criminology. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26, 467–479.

Tita, G., & Radil, S. (2011). Spatializing the social networks of gangs to explore patterns of violence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 4, 521–545.

Tita, G., & Ridgeway, G. (2007). The impact of gang formation on local patterns of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 2, 208–237.

Tita, G., Cohen, J., & Engberg, J. (2005). An ecological study of the location of gang set space. Social Problems, 2, 272–299.

UNODC. (2014). Global homicide statistics 2013. Vienna: United Nations Publication.

UNPD (2013) Regional human development report 2013–2014 – Citizen security with a human face: Evidence and proposals for Latin America. Tech. Rep., United Nations Development Programme.

Wheeler, J. (2014). Violence and authority in Rio’s favelas. Accord Series, 25, 95–99.

WHO. (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Xie, M. (2010). The effects of multiple dimensions of residential segregation on black and Hispanic homicide victimization. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26, 237–268.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions that helped to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

The Urban Infrastructure Index

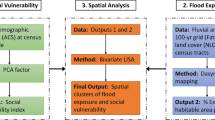

The urbanization index is generated by the Principal Components Approach (PCA). We include in the vector of variables: % of domiciles in unpaved streets (C1), % of domiciles in streets without trees (C2), % of domiciles without access to street light (C3), % of domiciles without sidewalk (C4), % of domiciles in streets without curbs (C5), and % of domiciles in streets without culverts (C6).

Table 8 shows the eigenvalues and eigenvectors obtained from PCA. We use the component with the largest eigenvalue to create the index which has an average of zero, varying from −2.5 to 6.19. Large values mean low access to urban infrastructure. We transform the index using the following expression:

where Xi is the value of the index for neighborhood i, whereas XMAX and XMIN are the maximum and minimum values of the series. After performing the transformation, we find a new index varying from 0 to 1. Notice that values near to 0 means low access to urban infrastructure and values near to 1 means high access to urban infrastructure.

The last column of Table 8 shows the correlation between the corresponding variable and the transformed index (URBINF). The coefficients show that the index is highly correlated to the proportion of domiciles without access to paved streets and sidewalk. The transformed index is less correlated to the proportion of domiciles without access to culverts.

Appendix 2

Urban Districts with Gang Conflicts in Fortaleza

In Fig. 4a, the urban districts of Fortaleza with large-scale gang conflicts in 2011 are: Barra do Ceará, Pirambu, Bom Jardim, Aerolândia, Jardim das Oliveiras, Messejana, and Jangurussu (see de Castro 2014). In Fig. 4b, urban districts with high-scale (red color) of gang conflicts are: Antônio Bezerra, Arraial Moura Brasil, Barra do Ceará, Bom Jardim, Edson Queiroz, Genbaú, Jacarecanga, José de Alencar, Messejana, Parque Dois Irmãos, Pici, Pirambu, Praia de Iracema, Sapiranga, and Vila Velha. While the urban districts with low-scale gang conflicts (orange color) are: Aerolândia, Barroso, Canindezinho, Conjunto Ceará I, Conjunto Ceará II, Conjunto Palmeiras, Granja Lisboa, Guajerú, Itaperi, Maraponga, Monte Castelo, Passaré, Praia do Futuro I, Praia do Futuro II, Siqueira, Serrinha, and Vincente Pinzon.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira, V.H., de Medeiros, C.N. & Carvalho, J.R. Violence and Local Development in Fortaleza, Brazil: A Spatial Regression Analysis. Appl. Spatial Analysis 12, 147–166 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-017-9236-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-017-9236-4