Abstract

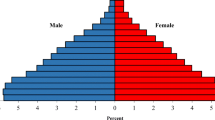

As the aging population increases, the demand for informal caregiving is becoming an ever more important concern for researchers and policy-makers alike. To shed light on the implications of informal caregiving, this paper reviews current research on its impact on three areas of caregivers’ lives: employment, health, and family. Because the literature is inherently interdisciplinary, the research designs, sampling procedures, and statistical methods used are heterogeneous. Nevertheless, we are still able to draw several important conclusions: first, despite the prevalence of informal caregiving and its primary association with lower levels of employment, the affected labor force is seemingly small. Second, such caregiving tends to lower the quality of the caregiver’s psychological health, which also has a negative impact on physical health outcomes. Third, the implications for family life remain under investigated. The research findings also differ strongly among subgroups, although they do suggest that female, spousal, and intense caregivers tend to be the most affected by caregiving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The literature was identified by using the following key works and their combinations in Google Scholar, Scopus, and Science Direct: “elderly care,” “informal care,” “aged care,” “employment,” “labor force participation,” “work,” “work hours,” “wage,” “health,” “burden,” “well-being,” “family,” and “relationship.” We also screened the references for any important omissions.

Because the research on implications for the family was sparse, we extended the time span for this topic to a few literature reviews published prior to 2000.

See Albertini et al. (2007) for a theoretical and empirical discussion of European family transfers.

In 2011, 2.5 million people received benefits from the German LTCI, which equals about 3.1 % of the population.

Such research commonly employs one of two survey methods: (i) diary methods, considered the gold standard because they bring in the most accurate information about time use, and (ii) recall methods, which are more widely used because they are easier and cheaper to carry out (Van den Berg et al. 2004).

For example, the 2001 UK census reported 5.2 million informal caregivers in England and Wales, while the 2000 General Household Survey identified 6.8 million for the entire UK (Heitmueller 2007).

Austria, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden.

The three commonest methods for valuing the amount of informal care are (i) using the caregiver’s opportunity to value the time that could be used to supply labor elsewhere, (ii) valuing the time provided according to possible market substitutes (e.g., nurses or unskilled workers), and (iii) using the caregivers’ reported well-being and valuing the mean time spent on caregiving based on the rise in income necessary to keep caregiver well-being constant when providing one additional hour of care (Van den Berg and Ferrer-i Carbonell 2007). The second method, often termed the “proxy good method,” is the most widely used because of its ease of application (for further information, see Van den Berg et al. 2004, 2005; Van den Berg and Spauwen 2006; Sousa-Poza et al. 2001).

Price varies based on the family relationship between care recipient and caregiver, with family caregiving requiring higher monetary compensation.

Individuals in year t-1 before they become actual caregivers.

For a list of other possible mediators suggested in pre-2006 studies, see Lilly et al. (2007).

Carmichael and Charles (2003) note that they themselves define the direction of causality in this paper arbitrarily. In particular, they assume that care choices are made exogenously and do not consider opportunity costs, although they do not rule out the possible interaction between the mutual effects of care and employment.

The authors divide Europe into the following three areas: (1) Nordic (Sweden and Denmark); (2) Central (Germany, France, Netherlands, Austria, and Switzerland), and (3) Southern (Spain, Italy, and Greece).

“Wear-and-tear” refers to an increasing psychological burden over time, while “adaption” assumes a coping ability that reduces the burden in the long run (Brickman and Campbell 1971).

For details, see Table 2.

Bookwala (2009) observed three caregiver groups in three waves: T1 (1987–1988), T2 (1992–1994), and T3 (2001–2002). Caregivers in T1 were subjected to a baseline interview, “experienced caregivers” provided care in T2 and T3, but only “former caregivers” provided care in T2 and only “recent caregivers” in T3.

References

Albertini, M., Kohli, M., & Vogel, C. (2007). Intergenerational transfers of time and money in European families: common patterns—different regimes? Journal of European Social Policy, 17(4), 319–334.

Amirkhanyan, A., & Wolf, D. (2006). Parent care and the stress process: findings from panel data. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(5), S248–S255.

Antonovics, K., & Town, R. (2004). Are all the good men married? Uncovering the sources of the marital wage premium. American Economic Review, 94(2), 317–321.

Arno, P. S., Levine, C., & Memmott, M. M. (1999). The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Affairs, 18(2), 182–188.

Ashworth, M., & Baker, A. H. (2000). “Time and space”: carers’ views about respite care. Health & Social Care in the Community, 8(1), 50–56.

Becker, G. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal, 75(299), 493–517.

Bell, D., Otterbach, S., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2012). Work hours constraints and health. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 105–106, 33–55.

Berecki-Gisolf, J., Lucke, J., Hockey, R., & Dobson, A. (2008). Transitions into informal caregiving and out of paid employment of women in their 50s. Social Science & Medicine, 67(1), 122–127.

Bettio, F., & Verashchagina, A. (2010). Long-term care for the elderly: Provisions and providers in 33 European countries. Luxembourg: EU Expert Group on Gender and Employment.

Bittman, M., Hill, T., & Thomas, C. (2007). The impact of caring on informal carers’ employment, income and earnings: a longitudinal approach. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 42(2), 255–272.

Black, W., & Almeida, O. (2004). A systematic review of the association between the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and burden of care. International Psychogeriatrics, 16(3), 295–315.

Bobinac, A., Van Exel, N. J. A., Rutten, F. F. H., & Brouwer, W. B. F. (2010). Caring for and caring about: disentangling the caregiver effect and the family effect. Journal of Health Economics, 29(4), 549–556.

Bolin, K., Lindgren, B., & Lundborg, P. (2008a). Informal and formal care among single-living elderly in Europe. Health Economics, 17(3), 393–409.

Bolin, K., Lindgren, B., & Lundborg, P. (2008b). Your next of kin or your own career? Caring and working among the 50+ of Europe. Journal of Health Economics, 27(3), 718–738.

Bonsang, E. (2009). Does informal care from children to their elderly parents substitute for formal care in Europe? Journal of Health Economics, 28(1), 143–154.

Bookwala, J. (2009). The impact of parent care on marital quality and well-being in adult daughters and sons. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(3), 339–347.

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Apley (Ed.), Adaptation level theory: A Symposium (pp. 287–302). New York: Academic.

Brody, E. M., Litvin, S. J., Hoffman, C., & Kleban, M. H. (1995). Marital status of caregiving daughters and co-residence with dependent parents. Gerontologist, 35(1), 75–85.

Brown, J., Demou, E., Tristram, M. A., Gilmour, H., Sanati, K. A., & Macdonald, E. B. (2012). Employment status and health: understanding the health of the economically inactive population in Scotland. BMC Public Health, 12(327), 1–9.

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14(4), 320–327.

Bureau of Labour Statistics (Ed.). (2013). Unpaid eldercare in the United States, 2011–2012: Data from the American Time Use Survey. Washington: United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Carmichael, F., & Charles, S. (2003). The opportunity costs of informal care: does gender matter? Journal of Health Economics, 22(5), 781–803.

Carmichael, F., Charles, S., & Hulme, C. (2010). Who will care? Employment participation and willingness to supply informal care. Journal of Health Economics, 29(1), 182–190.

Carmichael, F., Hulme, C., Sheppard, S., & Connell, G. (2008). Work-life imbalance: informal care and paid employment in the UK. Feminist Economics, 14(2), 3–35.

Casado-Marin, D., Gracia Gomez, P., & Lopez Nicolas, A. (2011). Informal care and labour force participation among middle-aged women in Spain. SERIEs, 2(1), 1–29.

Chappell, N. L., & Reid, R. C. (2002). Burden and well-being among caregivers: examining the distinction. Gerontologist, 42(6), 772–780.

Ciani, E. (2012). Informal adult care and caregiver’s employment in Europe. Labour Economics, 19(2), 155–194.

Clark, R. E., Xie, H., Adachi-Mejia, A. M., & Sengupta, A. (2001). Substitution between formal and informal care for persons with severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 4(3), 123–132.

Coe, N., & Van Houtven, C. (2009). Caring for Mom and neglecting yourself? The health effects of caring for an elderly parent. Health Economics, 18(9), 991–1010.

Cohen, C. A., Colantonio, A., & Vernich, L. (2002). Positive aspects of caregiving: rounding out the caregiver experience. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 184–188.

Cooper, C., Balamurali, T. B. S., & Livingston, G. (2007). A systematic review of the prevalence and covariates of anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(2), 175–195.

Dautzenberg, M., Diederiks, J., Philipsen, H., Stevens, F., Tan, F., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2000). The competing demands of paid work and parent care: Middle-aged daughters providing assistance to elderly parents. Research on Aging, 67(2), 165–187.

Dujardin, C., Farfan-Portet, M.-I., Mitchell, R., Popham, F., Thomas, I., & Lorant, V. (2011). Does country influence the health burden of informal care? An international comparison between Belgium and Great Britain. Social Science & Medicine, 73(8), 1123–1132.

Etters, L., Goodall, D., & Harrison, B. E. (2008). Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20(8), 423–428.

European Commission (Ed.). (2011). Strategy for equality between women and men 2010–2015. Luxembourg: EC.

Farfan-Portet, M.-I., Popham, F., Mitchell, R., Swine, C., & Lorant, V. (2009). Caring, employment and health among adults of working age: evidence from Britain and Belgium. European Journal of Public Health, 20(1), 52–57.

Gautun, H., & Hagen, K. (2010). How do middle-aged employees combine work with caring for elderly parents? Community, Work & Family, 13(4), 393–409.

Gräsel, E. (2002). When home care ends—changes in the physical health of informal caregivers caring for dementia patients: a longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(5), 843–849.

Gronan, R. (1977). Leisure, home production and work the theory of the allocation of time revisited. Journal of Political Economy, 85(8), 1099–1123.

Hassink, W. H. J., & Van den Berg, B. (2011). Time-bound opportunity costs of informal care: consequences for access to professional care, caregiver support, and labour supply estimates. Social Science & Medicine, 74(10), 1508–1516.

Heitmueller, A. (2007). The chicken or the egg? Endogeneity in labour market participation of informal carers in England. Journal of Health Economics, 26(3), 536–559.

Heitmueller, A., & Inglis, K. (2007). The earnings of informal care: wage differentials and opportunity costs. Journal of Health Economics, 26(4), 821–841.

Helmert, U., & Shea, S. (1998). Family status and self-reported health in West Germany. Sozial-und Präventivmedizin, 43(3), 124–132.

Hirst, M. (2005). Carer distress: a prospective, population-based study. Social Science & Medicine, 61(3), 697–708.

Jiménez-Martín, S., & Prieto, C. V. (2012). The trade-off between formal and informal care in Spain. European Journal of Health Economics, 13(4), 461–490.

Johnson, R., & Lo Sasso, A. (2006). The impact of elder care on women’s labor supply. Inquiry, 43, 195–210.

Keating, N. C., Fast, J. E., Lero, D. S., Lucas, S. L., & Eales, J. (2014). A taxonomy of the economic costs of family care to adults. Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 3, 11–20.

Kemper, P., Komisar, H. L., & Alecxih, L. (2005). Long-term care over an uncertain future: what can current retirees expect? Inquiry, 42(4), 335–350.

King, D., & Pickard, L. (2013). When is a carer’s employment at risk? Longitudinal analysis of unpaid care and employment in midlife in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(3), 303–314.

Kotsadam, A. (2011). Does informal eldercare impede women’s employment? The case of European welfare states. Feminist Economics, 17(2), 121–144.

Langa, K. M., Chernew, M. E., Kabeto, M. U., Herzog, A. R., Ofstedal, M. B., Willis, R. J., Wallace, R. B., Mucha, L. M., Straus, W. L., & Fendrick, A. M. (2001). National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(11), 770–778.

Lawton, M. P., Moss, M., Hoffman, C., & Perkinson, M. (2000). Two transitions in daughters’ caregiving careers. Gerontologist, 40(4), 437–448.

Lee, Y. & Tang, F. (2013). More caregiving, less working: caregiving roles and gender difference. Journal of Applied Gerontology.

Legg, L., Weir, C. J., Langhorne, P., Smith, L. N., & Stott, D. J. (2013). Is informal care-giving independently associated with poor health? A population-based study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(1), 95–97.

Leigh, A. (2010). Informal care and labor market participation. Labour Economics, 17(1), 140–149.

Lilly, M., Laporte, A., & Coyte, P. C. (2007). Labor market work and home care’s unpaid caregivers: a systematic review of labor force participation rates, predictors of labor market withdrawal, and hours of work. Milbank Quarterly, 95(4), 641–690.

Lilly, M., Laporte, A., & Coyte, P. C. (2010). Do they care too much to work? The influence of caregiving intensity on the labour force participation of unpaid caregivers in Canada. Journal of Health Economics, 29(6), 895–903.

Lim, J., & Zebrack, B. (2004). Caring for family members with chronic physical illness: a critical review of caregiver literature. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 50.

Litvin, S. J., Albert, S. M., Brody, E. M., & Hoffman, C. (1995). Marital status, competing demands, and role priorities of parent-caring daughters. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 14(4), 372–390.

Meng, A. (2012). Informal home care and labor force participation of house hold members. Empirical Economics, 44(2), 959–979.

Mentzakis, E., McNamee, P., & Ryan, M. (2009). Who cares and how much: exploring the determinants of co-residential informal care. Review of Economics of the Household, 7(3), 283–303.

Michaud, P. C., Heitmueller, A., & Nazarov, Z. (2010). A dynamic analysis of informal care and employment in England. Labour Economics, 17(3), 455–465.

Moscarola, F. C. (2010). Informal caregiving and women’s work choices: lessons from the Netherlands. Labour, 24(1), 93–105.

Nguyen, H. T., & Connelly, L. B. (2014). The effect of unpaid caregiving intensity on labour force participation: results from a multinomial endogenous treatment model. Social Science & Medicine, 100, 115–122.

OECD (Ed.). (2011). Help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care. Paris: EC.

O’Reilly, D., Connolly, S., Rosato, M., & Patterson, C. (2008). Is caring associated with an increased risk of mortality? A longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 67(8), 1282–1290.

Pavalko, E. K., & Henderson, K. A. (2006). Combining care work and paid work: do workplace policies make a difference? Research on Aging, 28(3), 359–374.

Pezzin, L. E., Kemper, P., & Reschovsky, J. (1996). Does publicly provided home care substitute for family care? Experimental evidence with endogenous living arrangements. Journal of Human Resources, 31(3), 650–676.

Pezzin, L., & Schone, B. (1999). Intergenerational household formation, female labor supply and informal caregiving: a bargaining approach. Journal of Human Resources, 34(3), 475–503.

Pickard, L. (2012). Substitution between formal and informal care: a “natural experiment” in social policy in Britain between 1985 and 2000. Ageing and Society, 32(7), 1147–1175.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003a). Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(2), 112–128.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003b). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250–267.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(1), 33–45.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2007). Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(2), 126–137.

Polder, J. J., Bonneux, L., Meerding, W. J., & Van der Maas, P. J. (2002). Age-specific increases in health care costs. European Journal of Public Health, 12(1), 57–62.

Raschick, M., & Ingersoll-Dayton, B. (2004). The costs and rewards of caregiving among aging spouses and adult children. Family Relations, 53(3), 317–325.

Reid, R. C., Stajduhar, K. I., & Chappell, N. L. (2010). The impact of work interferences on family caregiver outcomes. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 29(3), 267–289.

Satariano, W. A., Minkler, M. A., & Langhauser, C. (1984). The significance of an ill spouse for assessing health differences in an elderly population. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 32(3), 187–190.

Savage, S., & Bailey, S. (2004). The impact of caring on caregivers’ mental health: a review of the literature. Australian Health Review, 27(1), 111–117.

Schmitz, H., & Stroka, M. A. (2013). Health and the double burden of full-time work and informal care provision: evidence from administrative data. Labour Economics, 24, 305–322.

Schneider, U. (2006). Informelle Pflege aus ökonomischer Sicht [Informal care from an economic perspective]. Zeitschrift für Sozialreform, 52(4), 493–520.

Schoenmakers, B., Buntinx, F., & Delepeleire, J. (2010). Factors determining the impact of care-giving on caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. A systematic literature review. Maturitas, 66(2), 191–200.

Schulz, R., & Beach, S. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. Journal of the American Medical, 282(23), 2215–2219.

Schulz, R., O’Brien, A. T., Bookwala, J., & Fleissner, K. (1995). Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist, 35(6), 771–791.

Schulz, R., Visintainer, P., & Williamson, G. M. (1990). Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of caregiving. Journal of Gerontology, 45(5), 181–191.

Schwarzkopf, L., Menn, P., Leidl, R., Wunder, S., Mehlig, H., Marx, P., Graessel, E., & Holle, R. (2012). Excess costs of dementia disorders and the role of age and gender: an analysis of German health and long-term care insurance claims data. Health Services Research, 12(165), 1–12.

Sousa-Poza, A., Schmid, H., & Widmer, R. (2001). The allocation and value of time assigned to housework and child-care: an analysis for Switzerland. Journal of Population Economics, 14(4), 599–618.

Spiess, C. K., & Schneider, U. (2003). Interactions between care-giving and paid work hours among European midlife women, 1994 to 1996. Ageing and Society, 23(1), 41–68.

Triantafillou, J., Naiditch, M., Repkova, K., Stiehr, K., Carretero, S., Emilsson, T., Di Santo, P., Bednarik, R., Brichtova, L., Ceruzzi, F., Cordero, L., Mastroyiannakis, T., Ferrando, M., Mingot, K., Ritter, J., & Vlantoni, D. (2010). Informal care in the long-term care system. Athens/Vienna: Interlinks European Overview Paper.

Ugreninov, E. (2013). Offspring in squeeze: health and sick leave absence among middle-aged informal caregivers. Journal of Population Ageing, 6(4), 3 23–338.

Van den Berg, B., Al, M., Brouwer, W., Van Exel, J., & Koopmanschap, M. (2005). Economic valuation of informal care: the conjoint measurement method applied to informal caregiving. Social Science & Medicine, 61(6), 1342–1355.

Van den Berg, B., Brouwer, W. B. F., & Koopmanschap, M. A. (2004). Economic valuation of informal care: an overview of methods and applications. European Journal of Health Economics, 5(1), 36–45.

Van den Berg, B., & Ferrer-i Carbonell, A. (2007). Monetary valuation of informal care: the well-being valuation method. Health Economics, 16, 1227–1244.

Van den Berg, B., & Spauwen, P. (2006). Measurement of informal care: an empirical study into the valid measurement of time spent on informal caregiving. Health Economics, 15(5), 447–460.

Van Houtven, C. H., Coe, N. B., & Skira, M. M. (2013). The effect of informal care on work and wages. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 240–252.

Van Houtven, C. H., & Norton, E. C. (2004). Informal care and health care use of older adults. Journal of Health Economics, 23(6), 1159–1180.

Viitanen, T. (2010). Informal eldercare across Europe: estimates from the European Community Household Panel. Economic Analysis and Policy, 40(2), 149–178.

Vitaliano, P. P., Zhang, J., & Scanlan, J. M. (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(6), 946–972.

Vlachantoni, A., Evandrou, M., Falkingham, J., & Robards, J. (2012). Informal care, health and mortality. Maturitas, 72(2), 114–118.

Wakabayashi, C., & Donato, K. M. (2005). Population research and policy review. Population Research and Policy Review, 24(5), 467–488.

Yee, J. L., & Schulz, R. (2000). Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist, 40(6), 643–644.

Young, H., & Grundy, E. (2008). Longitudinal perspectives on caregiving, employment history and marital status in midlife in England and Wales. Health & Social Care in the Community, 16(4), 388–399.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the project "Ageing, Work & Health" which is funded by the Pfizer-Stiftung fuer Geriatrie & Altersforschung. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bauer, J., Sousa-Poza, A. Impacts of Informal Caregiving on Caregiver Employment, Health, and Family. Population Ageing 8, 113–145 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-015-9116-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-015-9116-0