Abstract

Introduction

This observational study was designed to assess the use of spinal anesthesia with chloroprocaine in the context of ambulatory surgery.

Methods

A prospective, multicenter, observational study was carried out among 33 private or public centers between May 2014 and January 2015 and adult patients, scheduled for a short ambulatory surgery under spinal anesthesia with chloroprocaine. The primary outcomes were anesthetic effectiveness, defined as performance of the whole surgical procedure without any additional anesthetic agent, and the time to achieve eligibility for hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes were the effect of chloroprocaine on motor and sensory blocks, patients’ satisfaction, and the use of analgesics in the first 24 h after surgery.

Results

Among the 615 enrolled patients, 56% were male, the mean age was 47.2 ± 15.2 years, and most patients had an ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) status of 1 (63.7%). Main surgical procedures performed were orthopedic (62.6%) and gynecologic (16.1%), and the mean duration of surgery was 26.7 ± 16.7 min. The overall anesthetic success rate was 93.8% (95% CI [91.5%; 95.6%]) for the 580 patients with available data for primary criteria. The failure rate was lower than 7% for all surgical procedures, except for gynecologic surgery (14.8%; 95% CI [8.1%; 23.9%]). The average times of eligibility for hospital discharge and effective discharge were 252.7 ± 82.7 min and 313.8 ± 109.9 min, respectively. The time of eligibility for hospital discharge is defined as the recovery of the patient’s normal clinical parameters and the time of effective discharge is defined as the time for the patient to leave the hospital after surgery. Eligibility for patient’s discharge was achieved more rapidly in private than public hospitals (236.3 ± 77.2 min vs. 280.9 ± 80.7 min, respectively, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

This study showed positive results on the effectiveness of chloroprocaine as a short-duration anesthetic and could be used to reduce the time to achieve eligibility for hospital discharge.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02152293. Registered on May 6, 2014. Date of enrollment of the first participant in the trial May 7, 2014.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why carry out this study? |

To find out an alternative to routine anesthesia to reduce the duration of motor blockade that may preclude patients’ hospital discharge |

To assess the use of spinal anesthesia with chloroprocaine in the context of ambulatory anesthesia |

What was learned from the study? |

This study showed positive results on the effectiveness of chloroprocaine as a short-duration anesthetic |

Chloroprocaine could be used to reduce the time to achieve eligibility for hospital discharge |

Chloroprocaine can be used as a local anesthetic in a broad variety of surgical procedures |

Introduction

A national consensus about ambulatory surgery has been developed to improve patient healthcare quality. French Health Authorities, HAS (Haute Autorité de santé) and ANAP (Agence Nationale d’Appui à la Performance), supporting French health and social care organizations in their performance improvement, estimate more than 2 million inpatient admission procedures should be performed as ambulatory surgeries [1]. Spinal anesthesia is a reliable and efficient anesthetic technique for gynecologic, abdominal, and lower limb orthopedic or vascular surgeries. However, in ambulatory surgery, use of short-acting local anesthetics is necessary to reduce the duration of motor blockade induced by spinal anesthesia and the incidence of urinary retention that may preclude a patient’s discharge from hospital [2]. Although spinal lidocaine has been considered for a long time as the gold standard for short-duration local anesthesia, it has been withdrawn from clinical use in several countries, because of the spinal cord toxicity [3,4,5,6], leading anesthetists to use low doses of long-acting local anesthetics. However, the use of these long-acting local anesthetics may be a risk for the patient in terms of long duration blockade and additional risk of spinal block failure [7]. Moreover, studies show that chloroprocaine is an interesting alternative to lidocaine for surgical blocks and short surgical procedures [8, 9]. Chloroprocaine, a short-acting anesthetic agent, was launched in Europe in 2013 for spinal anesthesia in ambulatory surgery [10]. It has been shown that spinal chloroprocaine use is non-inferior to spinal bupivacaine in randomized clinical studies [7,8,9]. These studies also reported the benefit of spinal chloroprocaine with a faster recovery of patients’ autonomy. Data in ambulatory orthopedic surgery suggest that chloroprocaine is a reliable and sufficient anesthesia [11]. Camponovo and colleagues [12] showed that onsets of unassisted ambulation and hospital discharge were significantly faster in patients receiving chloroprocaine compared to patients receiving bupivacaine. Lacasse’s group [13] showed that the unassisted ambulation time and the time of patients’ hospital discharge eligibility were significantly shorter (by approximately 2 h) when using chloroprocaine compared to bupivacaine, and that the average time to readiness for discharge was also significantly reduced when using chloroprocaine (277 ± 87 min) compared to bupivacaine (353 ± 99 min).

Clinical trials are sometimes far from daily practice especially in the ambulatory setting. Indeed, side effects of spinal anesthesia may alter the effectiveness of the process. This real-life study was therefore designed to assess the effectiveness of chloroprocaine as a short-duration anesthetic for spinal anesthesia on patients undergoing ambulatory surgery.

Methods

This multicenter, prospective, observational study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of IDF 5 (Saint-Antoine Hospital, Paris, France) on May 6, 2014 and registered on ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT02152293). Thirty-three private and public hospitals offering ambulatory surgery facilities were short-listed under feasibility criteria and a balanced geographical distribution from the most exhaustive French database of hospitals offering outpatient surgeries (gynecological, orthopedic, urological, vascular, pelvic, digestive, and others) and having chloroprocaine in their hospital pharmacy. According to their evaluation of patients, surgical procedures, and environmental conditions such as patients’ physical and psychological conditions that may be a risk in anesthesia [14], recruited anesthetists were free to use spinal anesthesia and spinal isobaric chloroprocaine for ambulatory surgeries at different dosage. Anesthetists were free to choose chloroprocaine application depending on patients’ anthropometric characteristics and the need for surgery at a metameric level. Each center participating in this study included up to 45 consecutive patients for 10 months. A total of 620 adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) having spinal anesthesia for short-duration ambulatory surgeries were eligible and expected. Physicians could enroll, during pre-anesthesia visit, each patient who met the inclusion criteria, after they had given the information briefing and obtained the patient’s oral agreement. Indeed, French Committees for the Protection of Persons (CPP) and the National Commission for Research Involving the Human Person allow an oral agreement for “Interventional research that involves minimal risks and constraints” (choice of type of anesthesia for patients and by patients has been considered as minimal risk for patients). Adult patients, consulting for pre-anesthesia evaluation prior to a short ambulatory elective surgery, with a scheduled spinal anesthesia using chloroprocaine willing to complete a questionnaire for a satisfaction survey, informed of computer processing of personal medical data were eligible for study inclusion. Patients with a contraindication for spinal anesthesia or chloroprocaine use, and patients participating or having participated in an anesthetic clinical trial within 1 month before inclusion were excluded.

Patients’ data were collected during the pre-anesthesia visit and postoperative follow-up visit.

Since spinal anesthesia can be a stressful experience, premedication was administered to some patients to facilitate their comfort during anesthesia performance. Therefore intraoperative sedation is a common practice [15, 16]. After the spinal block procedure, the upper level of the sensory block was evaluated using the cold test, and motor blockade was assessed with a modified Bromage score [17]. The time to sensory and motor block achievement was recorded. Data regarding patients’ perception (pain and satisfaction) were collected using a self-administered questionnaire, completed at home 24 h after surgery. Worst pain and pain over the first 24-h period after the procedure were assessed using a 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS, from 0 = no pain to 10 = worst pain). Postoperative analgesic treatments taken by the patients were recorded. Overall patients’ satisfaction concerning anesthesia (from satisfied to unsatisfied) was also evaluated.

Sample size was calculated to determine the time to eligibility for discharge from hospital with a sufficient precision (7 or 8 min), while considering a standard deviation of around 90 min, as observed in a previous study [5] and around 10% of missing data or unusable files. The impact of chloroprocaine on ambulatory surgery was described according to a twofold component considering the anesthetic effectiveness and the time of eligibility for discharge. Anesthetic efficacy (defined as success if no additional anesthetic injection was required) was expressed as an overall success rate and was also described according to the type of surgery and type of clinical center (private or public). Time to reaching eligibility criteria for hospital discharge (complete regression of sensory block, spontaneous voiding, ability to walk, stable vital signs, no nausea, control of pain with oral treatment, ability to swallow liquids) was described as an average overall time, as well as by classes of time and according to type of surgery and type of clinical center. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated for evaluation criteria. Comparative analyses were conducted with a significance threshold of tests set at 5% with Fischer’s exact test for qualitative variables, Student’s t test for normally distributed quantitative variables, or Wilcoxon signed-rank non-parametric test for semi-quantitative or non-normally distributed quantitative variables. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS® software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC, USA).

Results

Study Population

A total of 33 centers included 620 patients between May 7, 2014 and January 26, 2015. Five patients who did not meet all the inclusion criteria were excluded from analysis. Among the 615 remaining patients, 35 did not meet the primary criteria since the time to eligibility for hospital discharge could not be assessed. Thus, 580 patients (94.3%) with available data for the primary criteria were included in the evaluable population (Fig. 1).

The mean age in the analyzed population was 47.2 ± 15.2 years (range 18–89 years) and patients were mostly men (56%). The mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.6 ± 4.7 kg/m2 with 34% of overweight patients (BMI between 25 and 29 kg/m2) and 14% of obese patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). The cohort included 63.7% of patients with ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) status 1 and 32.2% with ASA 2. Surgical procedures were orthopedic (62.6%), gynecologic (16.1%), urologic (7.2%), digestive (5.4%), pelvic (3.6%), and vascular (3.4%).

Spinal Anesthesia Modalities and Surgical Procedures

The most common dose of spinal chloroprocaine administered was 50 mg/5 ml (59.2%), then 40 mg/4 ml (32.3%), and a few patients had another dose (8.5%). Only one attempt was necessary to perform spinal anesthesia in most cases (93.8%). The overall success rate of spinal anesthesia was 93.8% (95% CI [91.5%; 95.6%]). It was 96.0% (95% CI [93.2%; 97.9%]) in the 302 patients with complete motor block. The failure rate (use of rescue anesthetics) was lower than 7% in all surgical procedures (Table 1), except in gynecologic surgery (14.8%; 95% CI [8.1%; 23.9%]). No significant difference in the anesthetic success rate was observed according to the patients’ characteristics (gender, age, obesity), spinal anesthesia features (dose of chloroprocaine, puncture site, number of punctures), time from the first injection to the beginning of surgery, or type of center (private or public) (Table 2). Complementary intravenous analgesia or sedation was administered to 23.5% of patients within a median delay of 20 [1; 75] min after spinal injection to ensure patient comfort.

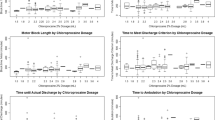

The mean onset time of motor block was 8.8 ± 4.8 min (median 8 min, [0; 30]). According to the modified Bromage score, the motor block was complete in 52.2% of the patients, almost complete in 38.4%, partial in 7.8%, and insufficient in 1.6%. The median upper level of sensory block was T10 (range T1–T12). The mean time to achieve sensory block at the T10 dermatome was 10.1 ± 6.3 min (median 9 min, [1; 40]). The surgical procedure started 20.2 ± 8.3 min after the first anesthetic injection in 84.5% of the patients (median 19 min, [5; 58]). The mean duration of surgery was 26.7 ± 17.6 min (median 23 min [3; 150]). The time from injection to surgical incision was comparable in private and public hospital centers (median 16 min in public centers vs. 20 min in private centers). The mean duration of the sensory block was 92.8 ± 38.4 min (median 85 min, [16; 315]). The mean time from spinal block to walking without assistance was 181.9 ± 77.5 min (median 168 min [30; 557]). Spontaneous voiding occurred in 85.6% of the patients, within 195.5 ± 67.0 min (median 185 min, [58; 520]); 14.2% of the patients were discharged from hospital without voiding and one patient (0.2%) required bladder catheterization. The mean time from the end of the procedure to the first analgesic demand was 121.4 ± 120.5 min (median 90 min [0; 713]). The use of intravenous vasoactive agents was required in 61 patients (10.5%).

The delay for hospital discharge was 252.7 ± 82.7 min (median 240 min [90; 640]), the mean time to effective discharge was 313.8 ± 109.9 min (median 290 min [90; 1217]), and the mean time from eligibility for discharge to the effective discharge was 62.1 ± 74.4 min (median 45 min [0; 1020]). In patients with complete motor blockade the time to eligibility for hospital discharge was 253.5 ± 83.6 min (median 238 min [118–538]) and did not differ significantly depending on the surgical procedure (Table 3). The mean time to eligibility for discharge was significantly shorter (p < 0.001) in private than in public hospitals (236.3 ± 77.2 min vs. 280.9 ± 80.7 min, respectively; p < 0.001) as was the mean time to effective discharge (296.2 ± 97.8 min vs. 340.8 ± 96.6 min, respectively; p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 5 reports failures and side effects observed in the analyzed population. Incision site pain was the most frequently reported adverse effect. Anesthetic complications accounted for 4.4% of all side effects.

Postoperative pain was assessed with a self-administered questionnaire (VAS score from 0 to 10), completed 24 h after the procedure. The mean pain score for the 24-h period after the procedure was 1.5 ± 1.8 (median 0.8, range 0–9) and the worst pain score over this period was 2.6 ± 2.4 (median 1.9 [0–10]) in the 485 patients whose self-administered questionnaires were available. For pain management most patients (87.6%) were given analgesics after discharge, mainly paracetamol (92.3%) and NSAIDs (53.3%). During the 24-h postoperative period, 68.9% of the patients required analgesia of which 67.0% used analgesics such as anilides (mainly paracetamol, 52.4%), NSAIDs (16.9%), natural opium alkaloids, and other opioids. Twelve patients (2.1%) were hospitalized after the procedure (data not shown). The reasons for unscheduled admissions were complications of surgery in nine patients; the three other patients experienced transient headache related to anesthesia, pain following general anesthesia, and side effects of tramadol, respectively.

The level of satisfaction regarding anesthesia was collected from 459 patients; the majority were very satisfied (67.5%) and only 1.1% were dissatisfied (Table 6)

Discussion

The results of this multicenter observational study suggest that spinal anesthesia using chloroprocaine is adapted to short-duration surgical procedures with a reasonably low incidence of failure. The anesthetic effectiveness was initially defined as the possibility to perform the surgical procedure under spinal anesthesia without any intravenous sedation or general anesthesia. Following the observation that most participating physicians commonly used perioperative intravenous analgesia or sedation in daily practice, the experts’ committee decided to change the definition of the anesthetic effectiveness. Patients received complementary sedation in most cases as a result of their anxiety status. Spinal anesthesia was thus defined as a success if no general anesthesia was required. In agreement, the overall anesthetic success rate (93.8%, 95% CI [91.5%; 95.6%]) in the conditions of daily practice was satisfactory. Kinsella [18] reported that insufficient spinal anesthesia with the need for general anesthesia occurred in 6.4% of cesarean sections. In this case, extension of sensory block up to T4 is required to make the patient comfortable, and isobaric chloroprocaine is less effective compared to hyperbaric local anesthetic solutions. According to Adenekan et al. [19], supplemental analgesia but not anesthesia was required in 6.4% of patients. In the current trial, no factors have been shown to interfere with anesthetic effectiveness, except for the type of surgery; gynecologic surgeries more commonly require additional anesthesia.

Half of the patients were eligible for hospital discharge within 4 h (and 95% within 11 h) and half of the patients had left the hospital within 5 h. These results are consistent with previous reports [12, 13]. However, the time spent in the hospital depends on surgical procedures and private and public hospitals’ organizational practices.

The time of eligibility for discharge was significantly shorter in private practice compared to public practice (median 227.0 vs. 284.0 min, p < 0.001) and anesthetic effectiveness of chloroprocaine was comparable in both private and public practices (94.4% vs. 91.6%, p = 0.282). Although patients in private hospitals reached eligibility for discharge more rapidly than in public hospitals, this observation is not related to surgical procedure. Indeed, there are no timeframe differences, neither from spinal injection to surgical incision nor for the mean duration of the procedure, in public hospitals versus private practice (Table 4). While this would require additional investigation, these results strongly suggest an organizational difference between public and private hospitals in France.

Hypotension and/or bradycardia requiring the administration of vasoactive agents during the procedure is commonly reported during spinal anesthesia. In this study the incidence of these side effects was 10.5%, in agreement with the current practice in spinal anesthesia [12, 13, 17,18,19,20]. No urinary retention or transient neurologic symptom was reported.

Postoperative spinal anesthesia side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, occurred in 7.2% and 2.2% of the patients, respectively (Table 5) in agreement with previous studies [13].

The mean postoperative pain score was low (1.52 ± 1.79 on a scale of 10). However, 68.9% of patients used analgesics in the first 24 postoperative hours. The other patients did not use analgesics because of the residual anesthetic effect that remains after the short-duration surgery. The use of rescue medication for postoperative pain control is expected to be more frequent with short-acting spinal anesthetic agents compared to long-acting anesthesia [20]. The use of 24-h postoperative analgesics in the current study is comparable to the observation of previous clinical trials [21]. Pain management was thus appropriate and resulted in a high satisfactory rate towards spinal anesthesia with 67.5% of patients being very satisfied and 28.8% rather satisfied.

Study Limitations

The authors recognize that chloroprocaine is not compared to another anesthetic in terms of effectiveness. However, its non-inferiority to bupivacaine has been previously described in the study by Lacasse et al. Current studies also suggest its non-inferiority to general anesthesia and its legitimacy to replace lidocaine [8, 22].

Patients undergoing various surgical procedures were included and the authors recognize that the types of surgery have not been defined in detail which could have been an inclusion and exclusion criteria. Correlation between type of surgery and puncture site may be further analyzed to investigate the impact on success and failure of anesthesia.

Since this is an observational study, the authors chose to include obese patients even though they may cause postoperative complications and influence the outcomes. Indeed, these results reflect real-life data.

Conclusions

This study confirms that spinal anesthesia with chloroprocaine is adapted to short surgical procedures and to ambulatory management. In addition to patients’ satisfaction, this study highlights the opportunity to use spinal anesthesia with a short-acting local anesthetic in a broad variety of surgical procedures.

References

Harousseau JL, Ritter P. Together for the development of day surgery. Day surgery: an overview. HAS and ANAP Technology Report. 2013;8–90.

Jouffroy L, Guidat A, et al. Prise en charge anesthésique des patients en hospitalisation ambulatoire. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2010;29:67–72.

Schneider M, et al. Transient neurologic toxicity after hyperbaric subarachnoid anesthesia with 5% lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 1993;76(5):1154–7.

Hampl KF, Schneider MC, Pargger H, Gut J, Drewe J, Drasner K. A similar incidence of transient neurologic symptoms after spinal anesthesia with 2% and 5% lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 1996;83(5):1051–4.

Freedman JM, Li D-K, Drasner K, Jaskela MC, Larsen B, Wi S. Transient neurologic symptoms after spinal anesthesia: an epidemiologic study of 1863 patients. Anesthesiology. 1998;89(3):633–41.

Nilsson U, Jaensson M, Dahlberg K, Hugelius K. Postoperative recovery after general and regional anesthesia in patients undergoing day surgery: a mixed methods study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2019;34(3):517–28.

Saporito A, et al. Does spinal chloroprocaine pharmacokinetic profile actually translate into a clinical advantage in terms of clinical outcomes when compared to low-dose spinal bupivacaine? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2019;52:99–104.

Ghisi D, Bonarelli S. Ambulatory surgery with chloroprocaine spinal anesthesia: a review. Ambul Anesth. 2015;2:111–20.

Goldblum E, Atchabahian A. The use of 2-chloroprocaine for spinal anaesthesia: chloroprocaine for spinal anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57(5):545–52.

HAS Transparency Committee. Intrathecal anaesthesia with chloroprocaine in adults planned surgery not lasting in excess of 40 minutes. 2013;1–15.

Gebhardt V, Hausen S, Weiss C, Schmittner MD. Using chloroprocaine for spinal anaesthesia in outpatient knee-arthroscopy results in earlier discharge and improved operating room efficiency compared to mepivacaine and prilocaine. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(9):3032–40.

Camponovo C, et al. Intrathecal 1% 2-chloroprocaine vs. 0.5% bupivacaine in ambulatory surgery: a prospective, observer-blinded, randomised, controlled trial: Spinal chloroprocaine vs. bupivacaine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(5):560–6.

Lacasse M-A, et al. Comparison of bupivacaine and 2-chloroprocaine for spinal anesthesia for outpatient surgery: a double-blind randomized trial. Can J Anesth Can Anesth. 2011;58(4):384–91.

Wolff A, Scemama-Clergue J. Pre-anesthetic consultation: what to say and how to say it? Rev Med Suisse. 2002;2.

Hu P, Harmon D, Frizelle H. Patient comfort during regional anesthesia. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(1):67–74.

Roh GU, Kim Y, Ha SH, Jeong KH, Choi S, Han DW. Modelling of the sedative effects of propofol in patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia: a pharmacodynamic analysis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;118(6):480–6.

Breen TW, Shapiro T, Glass B, Foster-Payne D, Oriol NE. Epidural anesthesia for labor in an ambulatory patient. Anesth Analg. 1993;77(5):919–24.

Kinsella SM. A prospective audit of regional anaesthesia failure in 5080 caesarean sections. Anaesthesia. 2008;63(8):822–32.

Adenekan AT, Olateju SO. Failed spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2011;1(4):1–17.

Teunkens A, Vermeulen K, Van Gerven E, Fieuws S, Van de Velde M, Rex S. Comparison of 2-chloroprocaine, bupivacaine, and lidocaine for spinal anesthesia in patients undergoing knee arthroscopy in an outpatient setting: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41(5):576–83.

Casati A, et al. Intrathecal 2-chloroprocaine for lower limb outpatient surgery: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, clinical evaluation. Anesth Analg. 2006;103(1):234–8.

Pierce J, et al. Efficiency of spinal anesthesia versus general anesthesia for lumbar spinal surgery: a retrospective analysis of 544 patients. Local Reg Anesth. 2017;10:91–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eric Leutenegger (Gecem, Montrouge, France) for the operational coordination of the study and all the study investigators.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee and Open Access fees were funded by Nordic Pharma.

Medical Writing Assistance

Nathalie Lee of KPL provided medical writing assistance. This assistance was funded by Nordic Pharma.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Xavier Capdevila and Francis Bonnet wrote this manuscript, which was closely reviewed by Paul Zetlaoui and Laurent Delaunay. Laurent Delaunay, Xavier Capdevila, Francis Bonnet, Hervé Bouaziz, Christophe Aveline, Paul Zetlaoui, Laurent Jouffroy, Olivier Choquet, and élène Herman-Demars designed the study, performed the investigation, and analyzed the data.

Disclosures

Francis Bonnet is a consultant for Nordic Pharma, Grünenthal, The Medicines Company, and Ambu. Xavier Capdevila is a consultant for Nordic Pharma and Grünenthal. Christophe Aveline is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Laurent Delaunay is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Hervé Bouaziz is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Paul Zetlaoui is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Olivier Choquet is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. Laurent Jouffroy is a consultant for Nordic Pharma. At the time of the study Laurent Jouffroy was an employee of Clinique des Diaconesses, Strasbourg, France and is now an employee of Clinique Rhéna, Strasbourg, France. Hélène Herman-Demars is an employee of Nordic Pharma.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the French Ethic Committee IDF 5 (Saint-Antoine Hospital, Paris, France) on May 6, 2014 and registered on ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT02152293). Physicians could enroll, at the time of a pre-anesthesia visit, each patient who met the inclusion criteria, after they had given the information briefing and obtained patients’ oral agreement. In France, the Committees for the Protection of Persons (CPP) and the National Commission for Research Involving the Human Person allow an oral agreement for “Interventional research that involves minimal risks and constraints”. As soon as the physician has to provide the anesthesia but gives only the choice of the type of anesthesia to the patient, this is considered as a minimal risk for the patient.

Data Availability

The data are available from GECEM, Montrouge, France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11213033.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Capdevila, X., Aveline, C., Delaunay, L. et al. Impact of Chloroprocaine on the Eligibility for Hospital Discharge in Patients Requiring Ambulatory Surgery Under Spinal Anesthesia: An Observational Multicenter Prospective Study. Adv Ther 37, 541–551 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01172-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01172-5