Abstract

Therapists and other health professionals might benefit from interventions that increase their self-compassion and other-focused concern since these may strengthen their relationships with clients, reduce the chances of empathetic distress fatigue and burnout and increase their well-being. This article aimed to review the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and loving-kindness mediation (LKM) in cultivating clinicians’ self-compassion and other-focused concern. Despite methodological limitations, the studies reviewed offer some support to the hypothesis that MBIs can increase self-compassion in health professionals, but provide a more mixed picture with regard to MBIs’ affect on other-focused concern. The latter finding may in part be due to ceiling effects; therefore future research, employing more sensitive measures, would be beneficial. Turning to LKM, there is encouraging preliminary evidence from non-clinician samples that LKM, or courses including LKM and related practices, can increase self-compassion and other-focused concern. As well as extending the LKM evidence base to health professionals and using more robust, large-scale designs, future research could usefully seek to identify the characteristics of people who find LKM challenging and the supports necessary to teach them LKM safely.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arguably, the capacity to be compassionate towards others is a key in psychotherapeutic and other clinical work (Gilbert 2005a). At the same time, continuous work with people in mental distress commonly leads to symptoms of psychological distress in clinicians, which may lead to burnout (Figley 2002; Hannigan et al. 2004). Over the past decades, Western psychology has increasingly become interested in training programmes that are thought to cultivate compassion for self and others, such as programmes based on mindfulness meditation (Gilbert 2005b; Kabat-Zinn 1990). Although the majority of research on mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) has been carried out with people with medical or mental health problems (e.g. Baer 2003), there has been growing interest in the use of MBIs to reduce stress and increase self-compassion and self-care in healthcare professionals (e.g. Shapiro and Carlson 2009). More recently, research has started to explore loving-kindness meditation (LKM), a traditionally Buddhist meditation which is commonly practised in the context of mindfulness (Hofman et al. 2011; Tirch 2010), and can cultivate an attitude of unconditional love, kindness and compassion for oneself and others (Gilbert 2005b; Salzberg 1995).

Within this context, it seems timely to review the literature on the role of MBIs and loving-kindness-based interventions in fostering self-compassion and other-focused concern in healthcare professionals. Before reviewing the empirical literature, we will consider definitions of relevant constructs.

Definitions of Constructs

According to Gilbert (2005b) compassion ‘involves being open to suffering of self and others, in a non-defensive and non-judgmental way’ (p.1) and includes a cognitive understanding of suffering as well as the motivation and behaviour directed to relieve suffering. Relatedly, Neff (2003) argues that self-compassion has three components: being kind rather than critical towards oneself, perceiving one’s experiences not so much as isolated but rather as part of common humanity and being aware and non-judgmental of one’s experiences rather than over-identifying with them.

Mindfulness has been described as a non-judgmental moment-to-moment awareness (Kabat-Zinn 1994), which Bishop et al. (2004) argue comprises two-components: a psychological process that regulates attention to focus on current experience, facilitating disengagement from worry or rumination, and an attitude of openness, curiosity and acceptance towards any arising experience.

Based on these definitions, mindfulness and compassion (for self and others) arguably differ in at least three important respects: firstly, mindfulness provides a way of relating to any experience, while compassion is specific to the context of suffering; secondly, compassion is directed towards oneself or other beings, while mindfulness is orientated towards experience more generally and finally, compassion could be seen as being more active than mindfulness, since it moves beyond acceptance of present-moment experience and includes the intention to bring a sense of concern and care to suffering.

That said, mindfulness is seen as an important foundation and component of compassion because self and other-focused compassion are created in an atmosphere of openness, awareness and acceptance of experience (cf. Gilbert 2010; Tirch 2010). Moreover, some have suggested compassion as a quality of mindfulness (Shapiro and Schwartz 2000) and others as an outcome of mindfulness practice (Bishop et al. 2004; Gilbert and Tirch 2009; Walsh 2008).

The close relationship between compassion and mindfulness is evidenced by the findings that post-MBI changes in mindfulness are correlated with changes in self-compassion (Birnie et al. 2010), and that mindfulness meditation is associated with changes in structure and activity of brain areas thought to be involved with caregiving behaviour, compassion and the experience of love (Cahn and Polich 2006; Lazar et al. 2005; Tirch 2010).

Turning to the concept of loving-kindness, this has been described as an unconditional love without desire for people or things to be a certain way; an ability to accept all parts of ourselves, others and life, including pleasurable and painful parts (Salzberg 1995). A key distinction between loving-kindness and compassion is that the latter is specifically directed towards suffering.

Finally, while measurement of self-compassion has been well developed by Neff (e.g. Neff 2003), unfortunately there is a lack of consensus regarding the measurement of compassion for others, with the terms compassion, empathy and sympathy sometimes being used interchangeably (Neff and Pommier 2012). Given that the evidence base is currently small, when we come to review it, we will take an inclusive approach and follow Neff and Pommier (2012) by using the umbrella concept of ‘other-focused concern’. This encapsulates compassion for others and closely related concepts, such as ‘empathetic concern’; the latter referring to feeling concern for the suffering of another.

The Importance of Self-Compassion and Other-Focused Concern

Before turning to the main focus of this review, it is helpful to briefly consider why self-compassion and other-focused concern seem important qualities for therapists and other clinicians to cultivate. Arguably, the relationship between client/patient and clinician is of relevance to any substantive client–clinician interaction. This relationship has been most studied with regard to psychotherapy, where compassion for others or components of this, in particular empathy and warmth, have been viewed as key factors in establishing good therapeutic relationships with clients (Ackerman and Hilsenroth 2003; Bennett-Levy 2005; Elliott et al. 2011). Empathy has been described as the ‘ability of the therapist to enter and understand, both affectively and cognitively, the client’s world’ (Hardy et al. 2007, p.29). Findings from a meta-analysis have shown that empathy accounts for about 9 % of outcome variance in psychotherapies (Elliott et al. 2011). It has further been estimated that the therapeutic alliance predicts about 30 % of psychotherapy outcome variance, compared with 15 % predicted by specific therapy techniques (Lambert and Barley 2001).

Klimecki and Singer (2011) argue that cultivating compassion for others may also offer healthcare professionals protection against the risks of burnout. In particular, they argue that if a clinician responds to their client/patient’s suffering with compassion, they will empathise with the suffering, but not identify with it, and thus will be able to contain their own negative feelings. In contrast, if a clinician responds with ‘empathetic/personal distress’, their identification with the suffering of their client could lead them to feel distressed, which over the longer term could lead to burnout. This distinction has lead Klimecki and Singer (2011) to propose that ‘compassion fatigue’ could more helpfully be thought of as ‘empathetic distress fatigue’. In summary, cultivating other-focused concern, in the form of empathy and compassion for others, has the potential to help healthcare professionals build stronger therapeutic relationships and may offer protection against burnout.

Turning to the cultivation of self-compassion, this could be helpful to clinicians both because it may play an important mediating role in maintaining their own mental health (cf. Kuyken et al. 2010; Ringenbach 2009) and because of the emerging evidence that self-compassion is usually associated with compassion for others (Neff and Pommier 2012).

Literature Review: the Effect of MBIs

MBIs, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn 1990) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al. 2002) are potential candidates as interventions to increase self-compassion and other-focused concern in healthcare professionals (cf. Shapiro and Carlson 2009). The literature concerning the effectiveness of MBIs in this regard will now be reviewed.

Method

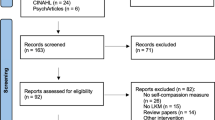

The following databases were searched up until week 3 in October 2011: PsycINFO, Assia, Web of Science, the British Nursing Index, Medline, and the Cochrane library. The search combined terms for ‘mindfulness’ with a number of terms for therapists and other healthcare professionals, such as medical personnel. Abstracts of articles were screened and references of relevant articles and books were hand searched for further references. Only publications in English were selected. Quantitative studies were included if they evaluated an MBI with healthcare professionals and measured self-compassion or other-focused concern, resulting in eight studies. In addition, four qualitative studies on MBIs with therapists were identified. The studies are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Findings

Studies Measuring Self-Compassion as the Outcome

All studies used the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) by Neff (2003) as an outcome measure. Two uncontrolled studies with clinical psychology trainees showed post-MBI increases in self-compassion (Moore 2008; Rimes and Wingrove 2011). Qualitative analysis of feedback questionnaires supported this finding and further suggested that participants felt more able to empathise with clients. Given the small sample sizes of these studies (n = 17 and n = 20, respectively), the generalizability of these findings is limited. Furthermore, results of the studies are difficult to compare due to the difference in the MBI used. Whereas Moore examined the impact of 14 ten-minute-long mindfulness sessions, Rimes and Wingrove evaluated an 8-week-long MBCT course. In addition, conclusions are limited due to the lack of control groups.

Using a cohort–controlled design and larger sample size (n = 64), Shapiro et al. (2007) examined the effects of an MBSR course on counselling students. The control group consisted of students taking part in psychology courses that had the same facilitator contact time as the MBSR group. Compared with the control group, the MBSR group showed an increase in self-compassion, which was related to changes in mindfulness. Although the study provided stronger evidence than uncontrolled studies, students volunteered to take part in the MBSR course, which may have biassed the results.

This problem of self-selection was addressed by an RCT that allocated 40 healthcare professionals into an MBSR group or wait list control (WLC) group (Shapiro et al. 2005). The MBSR group showed a significantly larger increase in self-compassion compared with the WLC group. Although RCTs provide the most robust evidence, neither this study nor the one by Shapiro et al. (2007) employed an active intervention as control group, leaving it uncertain whether changes in self-compassion were specifically due to the MBSR intervention or more generic factors. Moreover, none of the studies reviewed used follow-up assessments; thus it remains unclear how durable the changes in self-compassion are.

Studies Measuring Other-Focused Concern as the Outcome

Four studies used an uncontrolled pre–post design, measuring the impact of an MBSR or MBCT course on empathy. Three studies using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis 1983) as an outcome measures did not find any changes in empathy (Beddoe and Murphy 2004; Galantino et al. 2005; Rimes and Wingrove 2011), whereas the study using the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (Hojat et al. 2001) found a medium-size increase (d = 0.45) in empathy (Krasner et al. 2009), leading to questions about the sensitivity of the IRI to change. For example, Beddoe and Murphy attributed the absence of change to a ceiling effect and reported that baseline levels of empathy in participating nurses were 40–50 % higher than in non-nursing populations.

The study by Krasner et al. found that changes in mindfulness were positively correlated with increases in the empathy subscale of ‘perspective taking’ (r = .31). This study was the only one that conducted follow-up assessments, at 12 and 15 months, which showed that the increase in empathy was maintained over time. However, the absence of control groups in all four studies obviously limits the conclusiveness of findings.

Shapiro et al. (1998) used a matched-randomised control design in which 78 medical and premedical students were assigned to an MBSR or WLC group. Results demonstrated that empathy, as measured by the Empathy Construct Rating Scale (La Monica 1981), increased in the mindfulness group compared with the control group. However, the MBSR intervention also included empathic listening exercises, so it remains unclear which component(s) promoted change. Furthermore, results are limited due to the absence of an active control group and follow-up.

Qualitative Studies

Four qualitative studies explored the experience of MBI participants. Three studies were conducted by the same research group (Christopher and Maris 2010), examining the effects of a 15-week-long course, including mindfulness practice, Qigong exercises, and didactic material, on counselling students. The authors used content analysis on data from a focus group and journal assignments. Another study used thematic analysis on diaries of family therapy trainees about their experience of an MBI on their clinical practice (McCollum and Gehart 2010). The studies identified a perceived increase in participants’ self-awareness, self-compassion, and compassion towards others, including clients. Participants in all studies reported benefits for their clinical practice, such as an increased presence in sessions, tolerance to sit with silences, and an increased ability to focus on interpersonal processes and the client’s experience.

Drawing on Yardley’s (2000) validity criteria for qualitative studies, all studies showed sensitivity to the context, in particular to the position of trainees. For example, all authors reflected on the ethical challenge that mindfulness was being offered to trainees in the context of an evaluated training programme which researchers were actively involved with. All studies showed ‘commitment’, in that they demonstrated an in-depth engagement with the material and sufficient transparency with regards to the process of analysis, and provided a number of quotes to ground identified themes in the data. However, the generalizability of results from qualitative studies is limited. Moreover, the interventions either consisted of multiple components (i.e. meditation and qigong) or were embedded in clinical seminars; thus, findings might not be transferable to other MBIs.

Summary

Most of the quantitative studies reviewed used an uncontrolled design, self-report measures, self-selected samples, and had no follow-up assessments. Furthermore, some studies had small sample sizes. These methodological limitations constrain the validity and generalizability of the results. Despite these limitations, the studies do provide encouraging evidence that MBIs may increase self-compassion in healthcare professionals. Furthermore, the mixed evidence with regard to the effect of MBIs on other-focused concern may be partly due to ceiling effects in this population, which highlights the importance of ensuring that measures are sufficiently sensitive to change (Bishop et al. 2004; Hick and Bien 2008; Tirch 2010). The findings from the qualitative studies are consistent with the possibility that MBIs improve self-compassion and other-focused concern, though are limited in their generalizability. The evidence base would benefit from being extended by research addressing the methodological limitations discussed.

Literature Review: the Effect of Loving-Kindness-Based Interventions

To briefly recap, loving-kindness can be described as an unconditional love without desire for people or things to be a certain way, and an ability to accept all parts of ourselves, others, and life (Salzberg 1995). From a Buddhist psychology perspective, loving-kindness can be cultivated through loving-kindness meditation (LKM), and if loving-kindness is directed towards our own suffering then self-compassion can arise, while if it is directed towards the suffering of others then compassion for them can develop. Drawing on this tradition, there is growing interest in the scientific literature concerning the effects of loving-kindness meditation (e.g. Shapiro and Carlson 2009). The literature concerning the effectiveness of LKM in relation to cultivating self-compassion and other-focused concern will now be reviewed.

Method

A literature search using the search term ‘loving-kindness’ in different spellings was carried out to obtain studies that evaluated LKM or LKM-based courses. The databases PsycINFO, Assia, Web of Science, the British Nursing Index, Medline and the Cochrane library were searched up until week 3 in October 2011. No studies were found that focused solely on a healthcare professional sample. Therefore, we decided to include research involving other samples, on the grounds that it might be possible to tentatively generalise findings from these to our population of interest. Studies were included if they evaluated the impact of LKM on self-compassion or other-focused concern. In addition, a peer reviewer of this article identified a relevant in press study.

Findings

In an RCT with psychology students, Weibel (2007) found that four sessions of LKM resulted in an increase in self-compassion and compassion for others, relative to control. The study benefited from a randomised controlled design and 2-months follow-up, which showed that changes in self-compassion were maintained. The design of the study suffered from a lack of an active control group, and perhaps from the use of a relatively new measure of compassion for others (Sprecher and Fehr 2005).

In an experimental laboratory study, Hutcherson et al. (2008) showed that a brief loving-kindness exercise increased positive feelings and feelings of connectedness towards strangers. Although the findings further support the notion of LKM as a practice for increasing social connectedness and compassion for others (Salzberg 1995), their external validity is perhaps limited due to the artificial laboratory setting.

Results from a neurophysiological study suggest that LKM is related to an increased empathic response to social stimuli and an increased ability for perspective taking (Lutz et al. 2008). However, the study compared people experienced in LKM with novice meditators; therefore, differences between the two groups may have been due to other factors.

The most robust examination of LKM comes from an RCT in which Fredrickson et al. (2008) examined their broaden-and-build-theory. The authors proposed that LKM increases positive emotions, which in turn increase personal resources and wellbeing. Results supported the model, in that individuals participating in a 7-week LKM course experienced an increase in positive emotions over time, which predicted an increase in resources, including mindfulness, self-acceptance, received social support, and positive relations with others. These resources, in turn, predicted life satisfaction and reductions in depressive symptoms. A follow-up study showed that resources gained were maintained 15 months after the intervention (Cohn and Fredrickson 2010).

These studies did not identify any changes in compassion for others. However, compassion was measured by one item only, which the authors acknowledged might have lacked validity. Another limitation of the studies is the absence of an active control group. It is further noteworthy that results showed an initial drop in positive emotions, which did not improve until week 3. These findings suggest that practising LKM might not be of immediate benefit and may perhaps be challenging at first, but nevertheless appears worthwhile in the medium and longer term.

Recently, Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer have developed a Mindful Self-Compassion programme that follows a similar structure to MBSR and includes both LKM and compassion-focused variants of this. Their evaluation of this course is ongoing, but pilot RCT findings are encouraging, showing post-course increases in self-compassion and compassion for others, along with other benefits (Neff 2012).

Some potential challenges for participants engaging in LKM have been identified in other research. For example, an experimental study found that while some people showed a brain response associated with positive emotions to a brief LKM, others did not, in particular those with a tendency to ruminate (Barnhofer et al. 2010). Another experimental study found that, contrary to their hypothesis, LKM resulted in an increase in a supposedly maladaptive belief that happiness is related to the achievement of specific targets in life, which has been shown to be related to depression (Crane et al. 2010). Although these studies have limitations, such as the use of only one 15-min long LKM exercises, the findings resonate with clinical impressions that some individuals initially struggle to engage with LKM (Barnhofer et al. 2010) and interventions used in compassion-focused therapy (Gilbert 2009).

Recent studies have shown that highly self-critical individuals exhibit a physiological threat response when trying to be more self-compassionate (Longe et al. 2010; Rockliff et al. 2008). Gilbert (2009) has hypothesised that compassion-focused interventions may trigger feelings of grief about the lack of feeling loved and cared for in childhood, and that individuals may hold negative beliefs about compassion (e.g. ‘I don’t deserve it’).

A qualitative study examining the experience of trainee therapists taking part in a six-session long LKM course has further strengthened the observation that engaging in LKM can be experienced as emotionally challenging, for at least some participants (Boellinghaus, under review). At the same time, the trainee therapists reported becoming more compassionate towards themselves and others, and experiencing benefits for their clinical work.

In summary, there is encouraging initial evidence that LKM, or courses including LKM and related practices, can have positive benefits, including increasing self-compassion and other-focused concern. Some participants seem to find engaging in LKM more of a challenge than others, though, at least for some, these initial challenges may be offset by subsequent gains. This tentatively suggests that pre-course suitability assessments and providing a safe learning environment may be particularly important in relation to LKM courses.

Clearly, these findings can only be tentatively generalised to healthcare professionals, since none of the samples were specific to this population. Nevertheless, so long as it is assumed that clinicians are not at ceiling in terms of self-compassion and other-focused concern, it seems plausible to hypothesise that the findings would generalise, and further research employing a clinician sample would appear warranted.

Conclusions

Interventions that support clinicians to cultivate self-compassion and other-focused concern have the potential to help strengthen their relationships with clients, reduce their chances of empathetic distress fatigue and burnout, and maintain their wellbeing. Despite methodological limitations, the studies reviewed here offer some support to the hypothesis that MBIs can increase self-compassion in healthcare professionals. However, the evidence with regard to the effect of MBIs on other-focused concern is more mixed, perhaps in part due to ceiling effects in this population. Future research, employing more sensitive measures, would be beneficial.

Turning to LKM, there is encouraging preliminary evidence that LKM, or courses including LKM and related practices, can increase self-compassion and other-focused concern. LKM studies including a clinician sample have not yet been published. However, it would be perhaps surprising if similar effects were not seen in such samples. As well as extending the evidence base to healthcare professionals, future research could usefully seek to identify the characteristics of people who find LKM challenging and the supports necessary to safely teach them LKM. In addition, more robust, larger-scale RCTs would be helpful in adding to the evidence base in relation to both MBIs and LKM for clinicians, and it would be interesting to see whether self-compassion and other-focused concern act as mediators between these interventions and client and clinician outcomes.

If, in due course, the developing evidence base provides more robust support for the effectiveness of MBIs and LKM in generating self-compassion and other-focused concern, it would be helpful to accelerate and expand the introduction of these interventions into healthcare professionals’ training courses and work-based settings.

References

Ackerman, S. J., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2003). A review of psychotherapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting on the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1–33.

Ashworth, C. D., Williamson, P., & Montano, D. (1984). A scale to measure physician beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care. Social Science and Medicine, 19, 1235–1238.

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45.

Barnhofer, T., Chittka, T., Nightingale, H., Visser, C., & Crane, C. (2010). State effects of two forms of meditation on prefrontal EEG asymmetry in previously depressed individuals. Mindfulness, 1, 21–27.

Beddoe, A. E., & Murphy, S. O. (2004). Does mindfulness decrease stress and foster empathy among nursing students? Journal of Nursing Education, 43, 305–312.

Bennett-Levy, J. (2005). Therapist skills: a cognitive model of their acquisition and refinement. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34, 57–78.

Birnie, K., Speca, M., & Carlson, L. E. (2010). Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress and Health, 26, 359–371.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Cahn, B. R., & Polich, J. (2006). Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 180–211.

Chrisman, J. A., Christopher, J. C., & Lichtenstein, S. J. (2009). Qigong as a mindfulness practice for counseling students: a qualitative enquiry. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 49, 236–257.

Christopher, J. C., & Maris, J. (2010). Integrating mindfulness as self-care into counselling and psychotherapy training. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 10, 114–125.

Christopher, J. C., Christopher, S. E., Dunnagan, T., & Schure, M. (2006). Teaching self-care through mindfulness practices: the application of yoga, meditation, and qigong to counselor training. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 46, 494–509.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Cohn, M., & Fredrickson, B. (2010). In search of durable positive psychology interventions: predictors and consequences of long-term positive behavior change. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 355–366.

Crane, C., Jandric, D., Barnhofer, T., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). Dispositional mindfulness, meditation, and conditional goal setting. Mindfulness, 1, 204–214.

Curran, S. L., Andrykowski, M. A., & Studts, J. L. (1995). Short Form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): psychometric information. Psychological Assessment, 7, 80–83.

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113–126.

Derogatis, L. R. (1977). The SCL-R-90 Manual I: Scoring, administration and procedures for the SCL-90. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research.

Derogatis, L. R. (1987). Derogatis Stress Profile (DSP): quantification of psychological stress. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine, 17, 30–54.

Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI brief symptom inventory. Administration, scoring, and procedures manual (4th ed.). Minneapolis: National Computer Systems.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Empathy. Psychotherapy, 48, 43–49.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 1433–1441.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062.

Galantino, M. L., Baime, M., Maguire, M., Szapary, P. O., & Farrar, J. T. (2005). Association of psychological and physiological measures of stress in health-care professionals during an 8-week mindfulness meditation program: mindfulness in practice. Stress and Health, 21, 255–261.

Gilbert, P. (2005a). Compassion and cruelty: a biopsychosocial approach. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 9–74). New York: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2005b). Compassion: conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. New York: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15, 199–208.

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy. London: Routledge.

Gilbert, P., & Tirch, D. (2009). Emotional memory, mindfulness and compassion. In F. Didonna (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (pp. 99–110). New York: Springer.

Hannigan, B., Edwards, D., & Burnard, P. (2004). Stress and stress management in clinical psychology: findings from a systematic review. Journal of Mental Health, 13, 235–245.

Hardy, G., Cahill, J., & Barkham, M. (2007). Active ingredients of the therapeutic relationship that promote client change: a research perspective. In P. Gilbert & R. L. Leahy (Eds.), The therapeutic relationship in the cognitive and behavioral psychotherapies (pp. 24–42). Hove: Routledge.

Hick, S. F., & Bien, T. (2008). Mindfulness and the therapeutic relationship. New York: Guilford Press.

Hofman, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 1126–1132.

Hojat, M., Mangione, S., Nasca, T. J., Cohen, M. J. M., Gonnella, J. S., Erdmann, J. B., et al. (2001). The Jefferson scale of physician empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 349–365.

Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion, 8, 720–724.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Dell Publishing.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in every day life. New York: Hyperion.

Kass, J., Friedman, R., Leserman, J., Zuttermeister, P., & Benson, H. (1991). Health outcomes and a new measure of spiritual experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 203–211.

Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and social neuroscience. In B. Oakley, A. Knafo, G. Madhavan, & D. S. Wilson (Eds.), Pathological altruism (pp. 368–383). New York: Oxford University Press.

Krasner, M. S., Epstein, R. M., Beckman, H., Suchman, A. L., Chapman, B., Mooney, C. J., et al. (2009). Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. Journal of the American Medical Association, 302, 1284–1293.

Kuyken, W., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., et al. (2010). How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 1105–1112.

La Monica, E. (1981). Construct validity of an empathy instrument. Research in Nursing and Health, 4, 389–400.

Lambert, M. J., & Barley, D. E. (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy, 38, 357–361.

Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., & Treadway, M. T. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport, 16, 1893–1897.

Longe, O., Maratos, F. A., Gilbert, P., Evans, G., Volker, F., Rockliff, H., et al. (2010). Having a word with yourself: neural correlates of self-criticism and self-reassurance. NeuroImage, 49, 1849–1856.

Lutz, A., Brefczynski-Lewis, J., Johnstone, T., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLoS ONE. http://www.plosone.org/article/info; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001897. Accessed May 10, 2011

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory: manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

McCollum, E. E., & Gehart, D. R. (2010). Using mindfulness meditation to teach beginning therapists therapeutic presence: a qualitative study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36, 347–360.

Moore, P. (2008). Introducing mindfulness to clinical psychologists in training: an experiential course of brief exercises. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 15, 331–337.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250.

Neff, K. D. (2012). The science of self-compassion. In C. Germer & R. Siegel (Eds.), Compassion and wisdom in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Neff, K. D., & Pommier, E. (2012). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self and Identity (in press)

Rimes, K. A., & Wingrove, J. (2011). Pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for trainee clinical psychologists. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39, 235–241.

Ringenbach, R. (2009). A comparison between counselors who practice meditation and those who do not on compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, burnout and self-compassion. Dissertation Abstracts International

Rockliff, H., Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Lightman, S., & Glover, D. (2008). A pilot exploration of heart rate variability and salivary cortisol responses to compassion focused-imagery. Journal of Clinical Neuropsychology, 5, 132–139.

Salzberg, S. (1995). Loving-kindness: the revolutionary art of happiness. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-markers: a brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 506–516.

Schure, M. B., Christopher, J., & Christopher, S. (2008). Mind-body medicine and the art of self-care: teaching mindfulness to counseling students through yoga, meditation, and qigong. Journal of Counseling and Development, 86, 46–56.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Shapiro, S. L., & Carlson, L. E. (2009). The art and science of mindfulness: integrating mindfulness into psychology and the helping professions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Shapiro, S. L., & Schwartz, G. E. (2000). The role of intention in self-regulation: toward intentional systemic mindfulness. In M. Bockaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 252–272). San Diego, CA: Academic.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 581–599.

Shapiro, S. L., Astin, J. A., Bishop, S. R., & Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management, 12, 164–176.

Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., & Biegel, G. M. (2007). Teaching self-care to caregivers: effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1, 105–115.

Sprecher, S., & Fehr, B. (2005). Compassionate love for close others and humanity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 629–651.

Tirch, D. D. (2010). Mindfulness as a context for the cultivation of compassion. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3, 113–123.

Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 284–304.

Walsh, R. A. (2008). Minfulness and empathy. In S. F. Hick & T. Bien (Eds.), Mindfulness and the therapeutic relationship (pp. 72–86). New York: Guildford Press.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Weibel, D. T. (2007). A loving-kindness intervention: boosting compassion for self and others. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, College of Arts and Sciences, Ohio University.

Yardley, L. (2000). Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology and Health, 15, 215–228.

Zigmond, A., & Snaith, R. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers, and especially for the clarification of the differences between mindfulness and compassion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boellinghaus, I., Jones, F.W. & Hutton, J. The Role of Mindfulness and Loving-Kindness Meditation in Cultivating Self-Compassion and Other-Focused Concern in Health Care Professionals. Mindfulness 5, 129–138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0158-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0158-6