Abstract

Although clinical interest has predominantly focused on mindfulness meditation, interest into the clinical utility of Buddhist-derived loving-kindness meditation (LKM) and compassion meditation (CM) is also growing. This paper follows the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and provides an evaluative systematic review of LKM and CM intervention studies. Five electronic academic databases were systematically searched to identify all intervention studies assessing changes in the symptom severity of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (text revision fourth edition) Axis I disorders in clinical samples and/or known concomitants thereof in subclinical/healthy samples. The comprehensive database search yielded 342 papers and 20 studies (comprising a total of 1,312 participants) were eligible for inclusion. The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies was then used to assess study quality. Participants demonstrated significant improvements across five psychopathology-relevant outcome domains: (i) positive and negative affect, (ii) psychological distress, (iii) positive thinking, (iv) interpersonal relations, and (v) empathic accuracy. It is concluded that LKM and CM interventions may have utility for treating a variety of psychopathologies. However, to overcome obstacles to clinical integration, a lessons-learned approach is recommended whereby issues encountered during the (ongoing) operationalization of mindfulness interventions are duly considered. In particular, there is a need to establish accurate working definitions for LKM and CM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Buddhist-derived meditation practices are increasingly being employed in the treatment of psychopathology. Throughout the last two decades, clinical interest has predominantly focused on mindfulness meditation, and specific mindfulness interventional approaches are increasingly being advocated and/or employed in the treatment of psychiatric disorders (see, for example, American Psychiatric Association (2010) and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2009) practice guidelines for the treatment of depression). However, in the last 10 years, there has also been a growth of interest into the clinical utility of other Buddhist meditative techniques (Shonin et al. 2014a). Of particular significance are novel interventions that integrate meditative techniques known as loving-kindness meditation (LKM) and compassion meditation (CM). Studies of LKM and CM interventions have demonstrated a broad range of psychopathology-related salutary outcomes that include improvements in the following (for example): (i) schizophrenia symptomatology (Johnson et al. 2011); (ii) positive and negative affect (May et al. 2012); (iii) depression, anxiety, and stress (Van Gordon et al. 2013); (iv) anger regulation (Carson et al. 2005); (v) personal resources (Fredrickson et al. 2008); (vi) the accuracy and encoding of social-relevant stimuli (Mascaro et al. 2013a, b); and (vii) affective processing (Desbordes et al. 2012).

CM is described in the psychological literature as the meditative development of affective empathy as part of the visceral sharing of others’ suffering (Shamay-Tsoory 2011). LKM is more concerned with the meditative cultivation of a feeling of love for all beings (Lee et al. 2012). Depending on whether they are practising LKM or CM, the meditation practitioner first establishes themselves in meditative absorption and then intentionally directs either compassionate (CM) or altruistic/loving (LKM) feelings towards a specific individual, group of individuals (which can also include sentient beings in general), and/or situation, and has conviction that they are tangibly enhancing the well-being of the person or persons concerned (Shonin et al. 2014c). Although CM and LKM interventions in clinical contexts are typically delivered using a secular format (i.e., without the explicit use of Buddhist terminology), the manner in which CM and LKM techniques are operationalized in clinical settings is still reasonably closely aligned with the traditional Buddhist model.

Buddhist Construction of Loving-Kindness and Compassion

Within Buddhism, loving-kindness (Sanskrit, maitrī) is defined as the wish for all sentient beings to have happiness and its causes (Bodhi 1994). Compassion (Sanskrit, karunā) is defined as the wish for all sentient beings to be free from suffering and its causes. In conjunction with “joy” (Sanskrit, muditā) and “equanimity” (Sanskrit, upeksā), loving-kindness and compassion make up what are collectively known as the “four immeasurable attitudes” (Sanskrit, catvāri brahmaviharas). Although in Buddhist meditation the four immeasurable attitudes are often generated and then emanated to other sentient beings one at a time, each attitude is deeply connected to, and reliant upon, the others. For example, the immeasurable attitude of joy highlights the Buddhist view that genuine loving-kindness and compassion can only develop in a mind that is “well-soaked” in meditative bliss, and that has transmuted both gross and subtle forms of ego-attachment (Khyentse 2007). Likewise, given the objective is to distribute loving-kindness and/or compassion in equal and unlimited measures to all sentient beings, the immeasurable attitude of equanimity emphasizes the need for total impartiality in one’s regard for others (for a detailed discussion of the four immeasurable attitudes, see Nanamoli 1979).

While the practices of compassion and loving-kindness are integral to all Buddhist traditions, this is particularly the case in Mahayana Buddhist schools (Shonin et al. 2014c). One of the fundamental principles of Mahayana Buddhism is the concept of bodhichitta. Bodhichitta is a Sanskrit word that means the “mind of awakening” and it refers to the discipline and attitude by which spiritual practice is undertaken with the cessation of others’ material and spiritual suffering as the ultimate aim (for a discussion of the different types of suffering in Buddhism, see Van Gordon et al. 2014b). Buddhist practitioners who adopt and act upon such an attitude are known as bodhisattvas (for more a detailed description of bodhichitta and the bodhisattva’s way of life, see Shantideva 1997). According to Shonin et al. (2014c), dedicating one’s life (and future lives) to alleviating the suffering of others represents a “win-win” scenario because it not only helps other beings both materially and spiritually but it also causes the meditation practitioner to assume a humble demeanour that is essential for (i) dismantling attachment to the “self,” and (ii) acquiring spiritual wisdom (for a discussion of the meaning of wisdom in Buddhism, see Shonin et al. 2014a). According to Buddhist thought, the wisdom deficit or ignorance that arises from being attached to an inherently existing self is the underlying cause of all forms of suffering, including the entire spectrum of psychological disorders (Shonin et al. 2014a).

One of the most common CM/LKM techniques employed in clinical settings derives from the Tibetan lojong (meaning mind training) Buddhist teachings (Shonin et al. 2014c). The lojong teachings are practiced within each of the four primary Tibetan Buddhist traditions (i.e., the Nyingma, Gelug, Kagyu, and Sakya) and include instructions on a meditation technique known as tonglen (meaning giving and taking or sending and receiving). Tonglen involves synchronizing the visualization practice of taking others’ suffering (i.e., compassion) and giving one’s own happiness (i.e., loving-kindness) with the in-breath and out-breath, respectively (Sogyal Rinpoche 1998). In this manner and according to Buddhist theory, the regular process of breathing in and out becomes spiritually productive and functions as a meditative referent that facilitates the maintenance of meditative and altruistic/compassionate awareness throughout daily activities (Shonin et al. 2014c).

As elucidated above, compassion and loving-kindness help to foster spiritual wisdom, but their effective cultivation is also dependent upon it. In other words, compassion and loving-kindness facilitate wisdom acquisition and wisdom in-turn facilitates the development of compassion and loving-kindness (Dalai Lama 2001). This spiritual wisdom or insight that develops in conjunction with compassion and loving-kindness is believed to play a vital role in bringing the meditation practitioner to the understanding that while compassion and loving-kindness arise from the wish for others to have happiness and be free of suffering, the prospect of an individual permanently eliminating the suffering of another individual is a fundamental impossibility (Van Gordon et al. 2014b). Indeed, Buddhism asserts that individuals must take responsibility for their own spiritual development and that an enlightened or saintly being can only play a supporting/guiding role (Shonin and Van Gordon 2014).

Thus, as stated by the Buddha in his teaching on The Four Noble Truths, “suffering exists” (the first noble truth) and the only means by which an individual can bring about the cessation of suffering (the third noble truth) is by walking the path (the forth noble truth) that acts upon its causes (the second noble truth). Therefore, true compassion and loving-kindness towards others arises due to the realization that unless individuals make the choice to enter the spiritual stream, not only will they suffer for an indefinite period, but there is actually nothing that can be done to prevent them from experiencing and reaping the consequences of their actions (known in Buddhism as karma) (Van Gordon et al. 2014b). It is when compassion and loving-kindness are cultivated as part of this panoramic perspective that the meditation practitioner truly begins to take responsibility for their own and others’ spiritual well-being and understands that any (so-called) compassionate act that does not directly or indirectly serve to guide others towards entering or progressing along the spiritual path is actually unproductive (Van Gordon et al. 2014b). Accordingly, exercising compassion and loving-kindness towards others in order to help them spiritually evolve might on certain occasions actually necessitate behaving in ways that others interpret as firm or unkind.

Previous Reviews of Loving-Kindness and Compassion Meditation

Hofmann et al. (2011) provided an impressive general review of LKM and CM exploring emotional-response, neuroendocrine, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. However, this review was (i) narrative (i.e., as opposed to systematic), (ii) not intended to focus exclusively on intervention studies and therefore did not include all LKM or CM intervention studies published at the time the review was conducted (examples of omitted studies are Johnson et al. 2009; Sears and Kraus 2009; Williams et al. 2005), and (iii) encompassing of some compassion techniques that were not explicitly based on meditation (e.g., Compassion Focused Therapy, Gilbert and Procter 2006). Likewise, the scope of the review of Hoffman et al. did not extend to include an assessment of study quality using a standardized assessment measure.

More recently, Galante et al. (2014) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the effects of “kindness-based meditation” on health and well-being in adult participants. A total of 22 studies (n = 1,747) were included in the meta-analysis which reported that kindness-based meditation was moderately effective in improving the following: (i) self-reported depression (Hedges’s g = 0.6), (ii) mindfulness (Hedges’s g = 0.61), (iii) self-compassion (Hedges’s g = 0.45), and (iv) positive emotions (Hedges g = 0.42). Although the meta-analysis provided a robust estimate of the efficacy of kindness-based meditation and thus complimented the earlier narrative review by Hofmann et al., it inevitably only provided a selective account of the overall findings from LKM and CM intervention studies as well as the types of LKM/CM interventions that have been employed as psychopathology treatments. More specifically, the meta-analysis by Galante et al. did not take into account (i) children or adolescent populations, (ii) studies that did not follow an RCT design (e.g., non-randomized controlled trials, longitudinal studies, uncontrolled interventions studies, etc.), and (iii) studies published since March 2013.

Furthermore, although the delineation of “kindness-based meditation” by Galante et al. was fitting for the purposes of their study, it was rather broad and in several respects incongruous with the traditional Buddhist interpretation of LKM and CM. For example, as part of their construction of kindness-based meditation, Galante et al. included both Buddhist and non-Buddhist (e.g., Christian) meditative approaches. Although, as outlined by the authors, loving-kindness and compassion are qualities central to the core values of most spiritual traditions, the manner in which the Buddhist teachings embody these qualities and the values Buddhism assigns to different states of psychological arousal (including feelings of loving-kindness and compassion) varies from other religious and/or spiritual systems (Tsai et al. 2007). Indeed, in addition to the existence within Buddhism of an extensive body of practice literature that is specifically concerned with mobilizing loving-kindness and compassion as meditative techniques, loving-kindness and compassion are considered to be distinct properties. Thus, where (for example) Galante et al. define compassion meditation as a special form of loving-kindness meditation (p. 2), this no longer accurately captures the Buddhist interpretation.

It is also worth mentioning that in addition to providing limited details on the design and format of the various interventions utilized, almost one third (31.8 %) of the studies included in the meta-analysis of Galante et al. involved a single-dose exposure to LKM or CM that lasted for less than half an hour. We would argue that rather than measuring the effectiveness of a course of psychotherapy or carefully formulated treatment plan, such studies are more akin to a one-off experimental design and are assessing state rather than trait changes in outcomes.

Objectives of the Current Systematic Review

Notwithstanding the growth of interest into the clinical utility of LKM and CM, a robust systematic review specifically focusing on studies of Buddhist-derived LKM and CM interventions for all age groups has not been undertaken to date. Likewise, a review providing an in-depth assessment of clinically relevant integration and rollout issues is yet to be undertaken. The purpose of this paper is therefore to conduct an evaluative systematic review of LKM and CM intervention studies that follows (where applicable) the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al. 2009) and that (i) specifically focuses on LKM and CM interventions that are based on the Buddhist model of compassion and/or loving-kindness, (ii) includes both randomized and non-randomized study designs, (iii) encompasses both adult and non-adult populations, and (iv) undertakes an assessment of clinical integration issues for LKM and CM interventions.

Method

Literature Search

A comprehensive literature search using MEDLINE, Science Direct, ISI Web of Knowledge, PsychInfo, and Google Scholar electronic academic databases was undertaken for studies published up to August 2014. These five electronic databases were selected in order to achieve the most effective balance between the comprehensiveness of literature coverage and instances of duplicate records being returned. Reference lists of retrieved articles and review papers were also examined for any further studies not identified by the initial database search. The search criteria used were compassion*, or mind-training, or loving-kindness, or metta (Pali for loving-kindness) in combination with (and) meditation, or therapy, or treatment, or program, or intervention, or training.

Selection of Studies and Outcomes

The inclusion criteria for further analysis were that the paper had to (i) have been published in a peer-reviewed journal in the English language (unpublished studies were excluded on the assumption that if a study’s design, method of data analysis, and standard of reporting meet the criteria required for publication in peer-reviewed academic journals, then a version of the manuscript will eventually appear in published form), (ii) report an empirical intervention study of an LKM and/or CM technique that was based on a Buddhist model of loving-kindness or compassion, (iii) include pre- and post-intervention measures of dependent variables with adequate statistical analysis, (iv) measure outcomes utilizing suitably validated self-report questionnaires, clinician-rated checklists, and/or standardized laboratory test procedures, and (v) assess changes in the symptom severity of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (text revision fourth edition; DSM-IV-TR) Axis I disorders in clinical samples and/or known concomitants thereof in subclinical/healthy samples (the DSM-IV-TR was the current DSM version [i.e., rather than the DSM-V] at the time the included studies were conducted). Papers were excluded from further analysis if they (i) contained no new empirical data (e.g., a theoretical and/or descriptive review paper), (ii) followed a single-participant design, (iii) reported only qualitative data, (iv) assessed non-psychopathology-relevant outcomes, (v) utilized a meditation technique in which compassion and/or loving-kindness were not central components (due to the fact that self-compassion represents a separate arm of the theoretical and empirical literature on the interventional use of Buddhist compassion [and given that self-compassion and compassion are actually very different practices], studies utilizing interventions that were primarily based on self-compassion techniques were excluded from the current review), (vi) evaluated interventions that were not primarily meditation-based, and (vii) followed a single-dose experimental/non-treatment design that measured only state (i.e., and not trait) changes in dependent variables.

Outcome Measures

The primary considered outcome measure was a change in the symptom severity of a DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorder. Secondary outcomes were known concomitants and risk factors for psychopathology such as emotional dysregulation, thought suppression, psychological distress, and psychopathology biomarkers (e.g., cortisol, C-reactive protein, salivary alpha-amylase, cytokines, etc.). Acceptable outcome assessment tools were suitably validated self-report psychometric tests, clinician-rated checklists, and/or standardized laboratory test procedures for measuring psychopathology biomarkers.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Abstracts were identified, retrieved, assessed, and shortlisted by one member of the research team. A second member of the research team audited the initial shortlist process for the purposes of validating the rationality of the first team member’s selection criteria. The same two assessors independently undertook a full-text review of all shortlisted abstracts. Disagreements relating to study eligibility were reconciled via discussion between the two assessors, and a 100 % consensus was reached in all cases.

Data were extracted from the included studies based on recommendations by Lipsey and Wilson (2001). Extracted data items included sample size, control-group design (e.g., wait-list, treatment-as-usual, comparative intervention, purpose-made active control condition, etc.), diagnosis (where applicable), intervention description, outcome measures, and pre-post and follow-up (where applicable) findings. Extracted data items were then compiled to form a brief description of each study (see “Results” section), and a qualitative and quantitative assessment of study quality was then undertaken (see “Quality Scoring” subsection for details of the quantitative assessment of study quality and see “Results” section for findings from both the qualitative and quantitative assessment arms). Finally, eligible studies were stratified into LKM, CM, and mixed-LKM and CM interventions.

A meta-analysis was deemed to be inappropriate due to heterogeneity between study designs, participant age and clinical status, intervention types, and target outcomes (Shonin et al. 2013a). Furthermore, as previously discussed, a meta-analysis based exclusively on RCTs has recently been conducted (see Galante et al. 2014).

Quality Scoring

The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS; National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools 2008) was used to assess the quality of the included studies. The QATQS is a manualized tool that can be used to gauge study quality across a range of interventional study designs (e.g., RCTs, non-randomized controlled trials, cohort study, case–control study, uncontrolled studies, etc.). The QATQS assesses methodological rigor across the following six domains: (i) selection bias (e.g., sample representative of the target population), (ii) design (e.g., randomization, appropriate randomization, suitable control group, etc.), (iii) confounders (e.g., significant differences between groups on baseline demographic or health-based variables, etc.), (iv) blinding (i.e., researcher blinding), (v) data collection method (e.g., appropriateness of assessment tools), and (vi) withdrawals and drop-outs (i.e., numbers of and reasons for). A quality score of 1 to 3 is awarded for each domain (i.e., 1 = strong, 2 = moderate, 3 = weak). Individual scores are then transposed onto a rating table and a global score is then calculated. An overall quality score of 1 (strong) is assigned for no weak ratings, 2 (moderate) for one weak rating, and an overall score of 3 (weak) is assigned if there are two or more weak ratings.

For each of the rated domains, the QATQS uses a series of questions in order to maximize objectivity and scoring consistency. For example, to assess study quality for the “confounders” component, the QATQS includes the following questions in order to guide the assessor: 1. Were there important differences between groups prior to the intervention (in race, sex, marital/family status, age, socioeconomic status, education, health status, and/or pre-intervention score on outcome measure)? and 2. If yes, indicate the percentage of relevant confounders that were controlled (either in the design (e.g., stratification, matching) or analysis)—possible response options: (i) 80–100 % (most), (ii) 60–79 % (some), (iii) less than 60 % (few or none), or (iv) Can’t Tell. In the current study, the QATQS scoring was independently conducted by two members of the research team, and any discrepancies were reconciled by discussion. A 100 % agreement was reached in all cases.

Results

Search Results

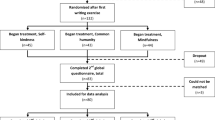

The initial comprehensive literature search yielded a total of 342 papers. After the review of the papers’ abstracts, 288 studies were found to be ineligible based on the predetermined inclusion and/or exclusion criteria outlined above. Following a full-text review of the remaining 54 papers, a total of 20 studies met all of the inclusion criteria for in-depth review and assessment. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the paper selection process.

Primary Reasons for Exclusion

Of the 54 papers that underwent a full-text review, the five most common reasons for exclusion were that the study: (i) featured a single-dose adapted LKM or CM experimental test rather than training as part of a program of psychotherapy (e.g., Barnhofer et al. 2010; Crane et al. 2010; Engström and Söderfeldt 2010; Feldman et al. 2010; Hutcherson et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2012; Logie and Frewen 2014), (ii) utilized an intervention integrating loving-kindness and/or compassion techniques that was not based on meditation (e.g., Gilbert and Procter 2006; Leiberg et al. 2011; Mayhew and Gilbert 2008; Oman et al. 2010), (iii) was not designed to explicitly assess changes in the symptom severity of DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders in clinical samples and/or known concomitants thereof in subclinical/healthy samples (e.g., Condon et al. 2013; Hunsinger et al. 2013; Mascaro et al. 2013a, b; May et al. 2011; Weng et al. 2013), (iv) was primarily based on self-compassion techniques (e.g., Albertson et al. 2014; Neff and Germer 2013; Shapira, and Mongraina 2010), or (v) was not published in a peer-reviewed journal (e.g., Humphrey 1999; Kleinman 2011; Law 2012; Templeton 2007; Weibel 2008).

Characteristics of Included Studies

The 20 papers that met all of the inclusion criteria comprised eight studies of LKM interventions, seven studies of CM interventions, and five studies of interventions that utilized both LKM and CM techniques. The mean QATQS quality score for the 20 included studies was 1.80 (SD = 0.70), indicating a moderate level of study quality. Fourteen studies employed an RCT design, three studies employed other controlled designs (e.g., non-randomized controlled trial), and three studies did not employ a control condition. Two studies included adolescent participants at-risk for psychopathology and the remaining 18 studies included adult participants of clinical, subclinical, or healthy diagnostic status. The total number of participants across all 20 studies was 1,312 (M = 65.60, SD = 47.45). Seven studies received a strong quality score, ten studies received a moderate quality score, and three studies received a weak quality score. Table 1 shows how the QATQS score was compiled for each study included in the in-depth analysis as well as a description of study characteristics.

Loving-Kindness Meditation Intervention Studies (n = 8)

Of the eight LKM intervention studies that met all of the inclusion criteria, five studies followed an RCT design, one study followed a non-randomized controlled design, and two studies did not employ a control group. The overall program duration of the eight eligible LKM studies ranged from 4 to 12 weeks and the length of weekly group sessions ranged from 10 to 120 minutes.

The first eligible LKM study was an RCT that investigated the effects of a manualized LKM intervention on patients with chronic lower back pain and associated psychological distress (Carson et al. 2005). Patients (mean age = 51.5 years, range = 26–80 years) were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 31) or a standard-care control group (n = 30). The 8-week intervention comprised 90-minute weekly group sessions facilitated by experienced clinicians. Patients were taught throughout successive weeks to direct feelings of love and kindness firstly towards themselves, then towards a neutral person (e.g., the postman), then towards a person who was a source of difficulty (e.g., a disrespectful former boss), and finally towards all living beings. Compared to controls, meditating participants demonstrated significant pre-test post-test and follow-up (3-month) reductions in pain intensity (McGill Pain Questionnaire, Melzack 1975) and psychological distress (Brief Symptom Inventory, Derogatis and Melisaratos 1983). Furthermore, daily practice-time predicted reductions in back pain that day as well as reductions in anger the following day.

While the study was methodologically robust, it could have been strengthened further by the inclusion of an intent-to-treat analysis. This would have provided a better indication of the overall ease of completion of the LKM intervention that suffered substantial attrition (of >40 %)—an amount that was significantly higher than the attrition rate for the control intervention (b = 1.28, p = 0.04). A further limitation was the poorly defined control condition whereby the authors simply stated that “patients in this condition received the routine care provided through their medical outpatient program” (p. 292). Thus, it is not possible to determine whether salutary effects experienced by the meditation group were due to non-specific factors (such as therapeutic alliance, psycho-education, etc.) that were absent from the control condition.

Another RCT evaluated the independent and interactive effects of LKM and massage on quality of life in individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (Williams et al. 2005). Participants (n = 58, mean age in LKM group = 45.08 years, SD = 2.20) were assigned to one of the following groups: (i) LKM, (ii) massage (five massages per week for a four-week period), (iii) LKM plus massage, or (iv) treatment as usual. Meditation group participants received a 90-minute introductory session lead by an experienced meditation teacher. Following this, participants were required to practice a guided LKM meditation (involving mind focusing and phrase repetition) at least once a day for a period of 4 weeks. Meditation participants met with the meditation instructor on a weekly basis to discuss any issues with the training. Following completion of the intervention and compared to the other allocation conditions, participants in the combined LKM and massage group demonstrated significant improvements in quality of life (Missoula-VITAS Quality of Life Index, Byock and Merriman 1998). There were no significant differences for standalone LKM or massage therapy compared to treatment as usual.

In addition to the small sample sizes (only 13 participants commenced the LKM intervention—of which 7 were lost to follow-up), the study was limited by the fact that (i) adherence to practice data was not assessed, and (ii) the control condition was “treatment as usual” which meant that a possible Hawthorne Effect could not be ruled out (i.e., where participant behavior changes simply because they are being observed).

A further RCT assessed the effects of a 6-week LKM intervention on positive emotions and associated changes in psychosocial resources (e.g., agency thinking, environmental mastery, social support given and received, etc.) and psychosomatic well-being (Fredrickson et al. 2008). Healthy adults (mean age = 41 years; SD = 9.6 years) employed at a computer company who were interested in reducing their levels of general stress were allocated to a wait-list control group (n = 100) or the intervention (n = 102). Approximately one in three participants dropped out of the study (with no significant variance between allocation conditions) or were disqualified (e.g., due to not attending the minimum number of weekly sessions). Meditating participants attended six 1-hour group sessions (20–30 participants per group) that were facilitated by a stress management specialist. The weekly meditation workshops were structured into three distinct phases (each of 20 minutes duration): (i) guided group meditation, (ii) didactic presentation, and (iii) question and answer sessions. A CD of guided meditations was provided to facilitate daily self-practice. Compared to control group participants, meditating participants demonstrated significant improvements in levels of positive emotions (e.g., love, joy, gratitude, interest—as measured by the Modified Differential Emotions Scale, Fredrickson et al. 2003). These improvements were associated with increases in personal resources which, in turn, predicted increased satisfaction with life (Satisfaction With Life Scale, Diener et al. 1985) and reductions in depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Measure, Radloff 1977).

While the study was well-conceived and adequate detail was provided regarding the intervention and study design protocol, it could have been strengthened further by (i) including a long-term follow-up assessment (e.g., at 3- or 6-months post intervention) to assess maintenance effects, (ii) providing information on worker profile (e.g., professional, managerial, skilled, unskilled, etc.) with an assessment of whether the intervention was more effective for different types of worker, and (iii) utilizing an active rather than a wait-list control (i.e., to control for factors such as group engagement, therapeutic alliance, change of work routine, team building, etc.).

In a non-randomized cohort controlled study (Sears and Kraus 2009) involving healthy college students (mean age = 22.8 years, SD = 6.7 years), four different study groups were generated: (i) mindfulness training (n = 24), (ii) LKM training (n = 20), (iii) adjunctive mindfulness with LKM training (n = 20), and (iv) non-meditating control group (n = 10). Participants in the first two groups attended group meditation sessions (10–15 minutes duration) once a week for a period of 12 weeks. The group receiving adjunctive mindfulness with LKM training attended 2-hour weekly group sessions for a period of 7 weeks. The dropout rate was below 25 % for both the mindfulness and LKM groups but was 45 % for the mixed-training group. The mean reported time of at-home practice was 25 minutes (SD = 39 minutes) with no significant difference between any of the meditating groups. No significant main effect of group or time was found across a range of outcome measures assessing psychosocial functioning (i.e., anxiety, positive and negative affect, irrational beliefs, coping styles, and hope). However, participants in the mixed-meditation group demonstrated significant within-group improvements in anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory, Beck et al. 1988), negative affect (Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Watson et al. 1988), and hope (Hope Scale, Snyder et al. 1991), which were mediated by changes in cognitive distortions (Irrational Beliefs Scale, Malouff and Schutte 1986).

The study was limited by a number of design issues: (i) differences between the number and duration of weekly sessions between meditation groups makes it difficult to draw reliable inferences regarding their relative effectiveness, (ii) participants were (seemingly) not provided with a CD of guided meditations to facilitate at home practice which increases the likelihood of deviations from the prescribed mode of meditative practice, (iii) post-intervention assessments were taken at different time points which makes it difficult to account for university term-related stressors (e.g., exams, coursework deadlines, etc.), and (iv) group sizes were small (i.e., 10–15 completing participants per group) and therefore may not generalize to larger samples.

An uncontrolled study exploring the effects of a secularized LKM intervention on the negative symptoms of schizophrenia met the criteria for inclusion in the systematic review (Johnson et al. 2009). Patients (n = 3) of young adult to middle age (exact age not reported) diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder attended 1-hour weekly group sessions for 6 weeks followed by a review/booster session 6 weeks after completion of the intervention. The sessions comprised discussion and clinician-guided meditation exercises. Patients were asked to practice LKM on a daily basis (and a guided meditation CD was provided as a support resource). Participants demonstrated significant improvements in asociality, blunted affect, self-motivation, interpersonal relationships, and relaxation capacity (pre- and post-intervention assessments were conducted by a clinician however details of the assessment instruments were not provided).

Obviously, the very small sample size considerably limits the generalizability of these findings as does the fact the authors did not provide a sufficient level of quantitative data regarding the assessments that took place pre- and post- intervention. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine to what extent improvements were due to LKM practice as opposed to therapeutic alliance or other therapeutic conditions (e.g., unconditional positive regard, active listening, accurate empathy, etc.) established during the weekly sessions.

More recently, the same authors (Johnson et al. 2011) replicated these findings in a slightly larger sample of outpatients (n = 18; mean age = 29.4 years, SD = 10.2 years) with a schizophrenia disorder (comprising persistent negative symptoms). The study was conducted on an intent-to-treat basis with data for non-completers (n = 2) substituted on a last-observation-carried-forward basis. The session attendance rate was 84 % with participants practicing LKM for an average of 3.7 days per week and an average of 19.1 minutes per individual practice session (SD = 14.6 minutes). Significant improvements in baseline to end-point scores were demonstrated across a range of outcomes including: (i) anhedonia and asociality (Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms, Blanchard et al. 2011), (ii) intensity of positive emotions (Modified Differential Emotions Scale, Fredrickson et al. 2003), (iii) consummatory pleasure (Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale, Gard et al. 2006), (iv) environmental mastery and self-acceptance (Scales of Psychological Well-being, Ryff 1989), and (v) satisfaction with life (Satisfaction with Life Scale, Diener et al. 1985). All intervention gains were maintained at the 3-month follow-up assessment and qualitative feedback attested to the accessibility and perceived utility of the intervention.

Similar to the earlier LKM study by the same authors (i.e., Johnson et al. 2009), the above study was limited by the small sample size and the absence of a control condition. Furthermore, the inclusion of mindfulness exercises as part of the LKM intervention made it difficult to establish whether LKM was in fact the active ingredient underlying the therapeutic change.

A longitudinal study was conducted to assess the effects of both LKM and concentrative meditation on mindfulness and positive/negative affect (May et al. 2012). Healthy adult student participants (mean age not reported) were randomly assigned to practice either concentrative meditation (n = 15) or LKM (n = 16) for a period of 5 weeks. Both groups attended an initial training session consisting of a 20-minute guided meditation. Participants were instructed to practice meditation for 15 minutes on 3 days each week. While practicing meditation, participants in both groups experienced significant improvements in levels of mindfulness (Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory, Walach et al. 2006). However, after completion of the 5-week intervention, mindfulness levels significantly decreased for the concentrative meditation group but not for the LKM group. A similar pattern was observed for affect where the concentrative meditation group demonstrated reductions in positive affect after the meditation training, while levels of positive affect in the LKM group continued to improve (Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Watson et al. 1988). The LKM group also demonstrated significant reductions in negative affect in the post-meditation period whereas no significant changes were observed for the concentrative meditation group.

Although findings suggest that LKM may give rise to more enduring salutary effects than concentrative meditation, there were a number of potentially confounding factors. These mostly relate to the relatively unstructured manner in which the two different forms of meditation where delivered, as well as apparent similarities between meditation techniques. For example, although participants received an initial 20-minute training session featuring a guided meditation, it appeared that no further formal instruction or guided meditation CD was provided. Based on such a small amount of instruction, it is possible that participants’ meditation practice will have deviated from the technique they were assigned to follow. Furthermore, although one group of participants was assigned to practice concentrative meditation and the other group LKM, both meditation conditions employed a significant amount of concentrative meditation. Indeed, a concentration-based body scan was taught as part of both meditative techniques, and the LKM group also included visualization/imagining tasks that are likewise heavily reliant upon meditative concentration.

In a further eligible study that utilized an RCT design, participants with high levels of self-criticism were randomly allocated to a LKM program (n = 19; mean age = 28.68, SD = 10.37) or a wait-list control condition (n = 19) (Shahar et al. 2014). Participants attended seven weekly 90-minute group sessions that were led by an experienced meditation teacher. Participants began by directing warmth and compassion towards themselves, and in subsequent weeks the focus of their meditation changed from friends, to neutral individuals, to persons with whom they had experienced relationship difficulties. The weekly session comprised various discussion components and participants were provided with a CD of guided LKM meditations to facilitate at-home practice. Compared to control-group participants, individuals in the LKM group demonstrated significant improvements in self-criticism (Dysfunctional Attitude Scale, Weissman and Beck 1978; Form of Self-Criticism and Self-reassurance Scale, Gilbert et al. 2004), depressive symptoms (depression subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21, Henry and Crawford 2005), self-compassion (Self-Compassion Scale, Neff 2003), and positive emotions (Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Watson et al. 1988). Therapeutic gains were maintained through to 3-month follow-up.

Although the intervention was described as LKM, limited information was provided about the meditation technique that was simply described as the process of directing warmth and compassion to others. Given that this account appears to resemble features of compassion meditation, it is difficult to establish whether participants were actually practising LKM, CM, or a combination of both. Further limitations of the study were the fact that: (i) the sample size was very small, (ii) participant practice-adherence data was not elicited, (iii) an active control condition was not employed (i.e., to control for non-specific factors), and (iv) only self-report (i.e., rather than objective) assessment tools were utilized.

Compassion Meditation Intervention Studies (n = 7)

Of the seven CM intervention studies that met all of criteria for inclusion in the systematic review, six studies followed an RCT design and one study did not employ a control group. The overall program duration of the seven eligible LKM studies ranged from 6 to 8 weeks and the length of weekly group sessions ranged from 50 to 120 minutes.

The first eligible RCT assessed the effects of Cognitive-based Compassion Training (CBCT) on stress reactivity in 89 healthy adults (aged 17–19 years; mean age = 18.5 years, SD = 0.62 years) (Pace et al. 2009). Participants attended twice-weekly group meditation classes (of 50-minute duration) for a total of 6 weeks. Of the 33 participants that completed the meditation training (n = 45 at baseline), the class attendance rate was 90 %. The average number of self-practice meditation sessions was 2.8 per week (mean session duration = 20 minutes). Participants in the control group attended health-based discussion workshops taught by graduate students. No significant pre-post differences were observed for meditating participants versus controls. However, a within-group association was identified for time spent meditating and reductions in innate immune (as measured by plasma concentrations of interleukin-6) and distress responses to psychosocial stress as induced by a standardized laboratory stressor (Trier Social Stress Test, Kirschbaum et al. 1993). Although the study included pre- and post-intervention assessments of some of the dependant variables, a major limitation of the study was the fact the stress test was administered only after the intervention. Thus, it is difficult to attribute any reduction in stress reactivity to time spent meditating because participants with lower baseline stress response levels may have been more able to practice meditation.

To overcome this limitation, the same authors (Pace et al. 2010) conducted a follow-up uncontrolled study using the same sample frame (n = 30) in which the stress test was administered at baseline. All 30 participants completed the 6-week CBCT program and no correlation was found between time spent meditating and stress responsivity. Findings from this smaller follow-up study suggest that the significant inverse associations reported in the original study (i.e., Pace et al. 2009) were not confounded by differences in participant pre-intervention stress reactivity levels.

While outcomes from both of the abovementioned studies (Pace et al. 2009, 2010) indicate that CBCT may exert a protective influence over psychosocial stress, there were a number of limitations that are likely to restrict the generalizability of findings. Of particular note was the design of the active control condition utilized in the original study. Although well-matched in terms of total intervention hours, degree of psychoeducation, group interaction, and an at-home practice element, the control intervention was delivered by graduate students. This is in contrast to the CBCT intervention that was delivered by a Buddhist monk who is likely to have more experience in delivering meditation-based interventions.

A more recent RCT (n = 71) of CBCT (two 1-hour weekly sessions for 6 weeks) assessed the effects of CM on adolescents (aged 13–17 years) with high rates of early-life adversity due to foster care placement (Pace et al. 2013). Participants were randomized to a 6-week CBCT program (n = 37) or to a wait-list control group (n = 34). Dropout rates were relatively similar between groups (approximately 20 % in each group). The primary measured outcome was changes in salivary concentration of C-reactive protein—an inflammatory biomarker for psychopathology. No significant improvements were observed for meditating participants versus controls. However, C-reactive protein levels in the CBCT group were negatively correlated with the number of meditation practice sessions attended. The authors interpreted these findings as an indication that CBCT exerts a protective influence over inflammation (and therefore psychopathology) caused by early life adversity.

Using the same sample of foster-care adolescents, another eligible RCT assessed the effects of CBCT on psychosocial outcomes including depression, anxiety, hope, self-injurious behavior, personal agency, emotion regulation, and childhood trauma (Reddy et al. 2012). Similar to the inflammatory biomarker study, no significant main effect of meditation was observed for any of the dependent variables. However, meditation practice time frequency was significantly associated with increased hopefulness (Children’s Hope Scale, Snyder et al. 1991). As part of an embedded qualitative arm, 62 % of CBCT participants reported that the program was very helpful for coping with daily life. In addition to limited statistical power (i.e., due to small sample sizes), the two adolescent CBCT studies were also limited by the use of a wait-list control condition that did not account for an effect of peer interaction (or other non-meditative therapeutic effects) that may have confounded the findings.

A further RCT investigated the effects of CBCT on empathic accuracy in healthy adult participants (Mascaro et al. 2013a). Participants (age range = 25–55 years, M = 31.0 years, SD = 6.0 years) were randomized to either an 8-week CBCT program (n = 16) or a health discussion (n = 13) control group. The CBCT program consisted of weekly 2-hour classes and participants were instructed to practice meditation at home for 20-minutes per day (and a CD of guided meditations was provided to facilitate at-home practice). Participants received functional MRI scans while completing an image-based empathic accuracy test (Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test, Baron-Cohen et al. 2001) that involved the deciphering of subtle social cues. Following the intervention, participants who completed the meditation program (n = 13) showed significant improvements over controls in empathic accuracy as well as increased neural activity in the inferior frontal gyrus and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex—areas of the brain associated with empathic accuracy and emotional-state mentalizing (Mascaro et al. 2013a). In addition to the small sample sizes, the study was limited by the fact the meditation intervention was administered by two purpose-trained experienced meditators while the control program was facilitated by relatively inexperienced graduate students. A further limitation was the fact the comparator condition (i.e., the health discussion program) did not control for all non-specific factors because it omitted an at-home practice element. Furthermore, fidelity of intervention implementation was not assessed which meant that any deviations from the intervention delivery protocol were not controlled for.

Another eligible study followed a three-arm RCT design and assessed the effects of compassion meditation on amygdala response to emotional stimuli (Desbordes et al. 2012). Healthy adults (n = 51) aged 25–55 years (M = 34.1 years, SD = 7.7 years) were randomized to one of three 8-week programs: (i) a mindfulness intervention, (ii) CBCT, or (iii) a non-meditating active control group featuring health-based discussions. Each allocation condition consisted of 2-hour weekly sessions (i.e., 16-hours total intervention time) with no significant differences in total meditation practice time for the mindfulness and CBCT groups. Functional MRI brain scans during an image-based emotion-eliciting task were taken pre- and post-intervention. Following the 8-week program, CBCT participants showed increases in right amygdala responses to negative images that were significantly correlated with reduced levels of depression. These outcomes were not observed in the mindfulness or control groups. This suggests that CM can lead to enduring changes in brain function and emotion regulation that are maintained outside periods of formal meditation practice.

Findings from the study should be considered cautiously due to the small sample sizes (i.e., only 12 completing participants per allocation condition). A further limitation was the fact that gender was not evenly matched across allocation conditions. This is particularly pertinent given that differences in amygdala activation have been observed between males and females during emotion eliciting tasks (e.g., Derntl et al. 2010; Proverbio et al. 2009). Furthermore, fidelity of intervention delivery was not assessed which meant that any deviations from the intervention delivery plan were not controlled for.

In a four-arm RCT investigating the effects of meditation on ideal affect (how people would actually like to feel), female students (n = 96, mean age = 21.13 years, SD = 3.49) were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: (i) mindfulness meditation, (ii) compassion meditation (based on Tibetan Buddhism), (iii) active control (instructor-led 8-week improvisational theatre class), or (iv) no intervention (Koopmann-Holm et al. 2013). Participants in the two meditation groups were without prior meditation experience and attended an 8-week guided meditation program. Weekly sessions lasted for 2 hours and all meditating participants received a CD of guided meditation to facilitate self-practice. At the end of the 8-week intervention, participants in both mediation groups (i.e., mindfulness meditation and compassion meditation) valued “low arousal positive states” (e.g., feeling calm) significantly more so than control group participants (Affect Valuation Index, Tsai and Knutson 2006). However, there were no significant differences between any of the groups in how participants valued other affective states (e.g., high arousal positive [e.g., excitement], low arousal negative [e.g., dullness], high arousal negative [e.g., fear]) or in levels of subjective well-being (Satisfaction With Life Scale, Diener et al. 1985).

In addition to the small sample size (the average number of participants per allocation condition completing end-point assessments was just 19), the study was limited by the absence of (i) a follow-up assessment to determine maintenance effects and (ii) objective measures of outcome variables (i.e., only self-report measures were employed).

Mixed Loving-Kindness and Compassion Meditation Intervention Studies (n = 5)

Of the five mixed-LKM and -CM intervention studies that met all of the criteria for inclusion in the systematic review, four studies followed an RCT design and one study employed a non-randomized controlled trial design. The program duration of each of the five eligible mixed-LKM and CM studies was 8 weeks and the length of weekly group sessions ranged from 75 to 120 minutes.

The first eligible mixed-meditation technique study was a non-randomized controlled trial that assessed the effectiveness of an 8-week group-based Meditation Awareness Training (MAT) program for improving stress, anxiety, and depression in a subclinical sample of 25 university students (Van Gordon et al. 2013). MAT is a secular intervention delivered by experienced meditators with a minimum of 3 years supervised meditation training. The program follows a more traditional approach to meditation in which participants receive training in both LKM and CM, as well as in other forms of meditation (e.g., mindfulness and insight meditation) and other Buddhist-derived practices (e.g., ethical awareness, patience, generosity, etc.). Participants (mean age = 30.3 years, SD = 8.6 years) attended weekly group sessions (120-minute duration) and received a CD of guided meditations to facilitate daily self-practice. The weekly sessions comprised three distinct phases: (i) a taught/presentation component (approximately 35 minutes), (ii) a facilitated group-discussion component (approximately 25 minutes), and (iii) a guided meditation and/or mindfulness exercise (approximately 20 minutes). In weeks 3 and 7 of the program, participants attended one-to-one therapeutic support sessions (50-minute duration) with the program facilitator. Meditating participants (completers = 11; dropouts = 3) demonstrated significant pre-post improvements compared to a wait-list control group (n = 11) in levels of (i) depression, anxiety, and stress (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale, Lovibond and Lovibond 1995); (ii) positive and negative affect (Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Watson et al. 1988); and (iii) dispositional mindfulness (Mindful Attention & Awareness Scale, Brown and Ryan 2003).

Although the intervention and control groups were appropriately matched on years of education and other demographic variables, outcomes may have been inflated due to differences in baseline levels of psychological distress between the two groups. In addition to the small sample size, a further limitation of the study was the absence of an active control group which meant that potential confounders such as therapeutic alliance and group engagement were not controlled for.

More recently, an RCT (n = 152) was conducted to access the effects of MAT on work-related stress and job performance in office managers (Shonin et al. 2014b). Participants followed the same intervention format as described above except the weekly sessions lasted for 90 instead of 120 minutes. Compared to a non-meditating active control group that received an 8-week psycho-education program, meditating participants (mean age = 40.14 years, SD = 8.11) demonstrated significant improvements in levels of (i) work-related stress (HSE Management Standards Work-Related Stress Indicator Tool [Health and Safety Executive, n.d.]), (ii) job satisfaction (Abridged Job in General Scale, Russel et al. 2004), (iii) psychological distress (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale, Lovibond and Lovibond 1995), and (iv) employer-rated job performance (Role-Based Performance Scale, Welbourne et al. 1998).

The RCT was limited by the fact the sample exclusively comprised highly motivated managers aspiring towards higher hierarchy lifestyles and career roles (annual salary range = £40,000–£65,000). Consequently, findings may not generalize to individuals fitting different occupational profiles (e.g., semi-skilled workers, skilled workers, etc.). Likewise, participants were essentially “treatment-seeking” workers interested in learning meditation in order to overcome work-related stress. Thus, findings may not generalize to individuals with an indifferent or negative attitude towards meditation.

A further eligible RCT investigated the effects of a mixed-LKM and -CM intervention on empathy and personal distress (Wallmark et al. 2013). Healthy adult participants (n = 50, mean age intervention group = 32, SD = 11, range = 22–57) were allocated to a wait-list control group or an 8-week meditation intervention. Each weekly session (75-minute duration) of the meditation program comprised the following phases: (i) lecture (30 minutes), (ii) mindful movements (10 minutes), (iii) guided meditation (20 minutes), and (iv) question and answer (15 minutes). Throughout the 8-week period, participants received training in meditation that was based on the four immeasurable attitudes (i.e., joy, compassion, loving-kindness, and equanimity), and in weeks 7 and 8 participants practiced guided tonglen exercises. The intervention was delivered by experienced meditators and participants received a CD of guided meditation to facilitate self-practice. Compared to the non-meditating control group, individuals that receiving the meditation intervention demonstrated significant improvements in the following: (i) perspective taking (Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Davis 1983), (ii) stress (Perceived Stress Scale, Cohen et al. 1983), (iii) self-compassion (Self-Compassion Scale, Neff 2003), and (iv) mindfulness (Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Baer et al. 2006).

In addition to the small sample size, the above RCT was limited by the absence of a follow-up assessment and an active control condition (i.e., to control for non-specific effects). Furthermore, the convenience sampling method employed meant that all participants (most of which were educated to degree level) were highly motivated to learn meditation. Consequently, findings may not generalize to other (i.e., less motivated) population groups.

Another RCT assessed the effects of Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT) on different indices of compassion (Jazaieri et al. 2013). Healthy adult participants (n = 100) were allocated to CCT (n = 60; mean age = 41.98, SD = 11.48) or a wait-list control group (n = 40). Participants attended eight weekly 2-hour group sessions (plus orientation session) and were required to practice meditation at home for 15–30 minutes each day (participants were provided with pre-recorded guided meditations). Each weekly group session comprised (i) pedagogical instruction, (ii) group discussion, (iii) guided group compassion and loving-kindness meditations, and (iv) exercises designed to prime feelings of open-heartedness and connection to others (e.g., poetry reading). The intervention was delivered by experienced meditators and no deviations from the CCT protocol were reported. CCT participants demonstrated significant improvements over control group participants in fear of compassion (Fears of Compassion Scales, Gilbert et al. 2010) and self-compassion (Self-Compassion Scale, Neff 2003). Participants practiced meditation for an average of 101 minutes each week and there were no significant differences between allocation conditions in attrition (51 out of 60 CCT participants completed the program).

Using the same RCT population and in addition to outcomes of fear of compassion and self-compassion, separately reported outcomes of mindfulness, affect, and emotion regulation were also assessed (Jazaieri et al. 2014). CCT participants demonstrated significant improvements over non-meditating participants in levels of mindfulness (Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills, Baer et al. 2004); Experiences Questionnaire, Fresco et al. 2007), worry (Penn State Worry Questionnaire, Meyer et al. 1990), and emotional suppression (Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, Gross and John 2003).

The RCT by Jazaieri et al. (2013, 2014) was limited by the absence of (i) a follow-up assessment to determine maintenance effects, (ii) an active control condition to rule-out non-specific effects (e.g., group interaction, therapeutic alliance, etc.), and (iii) objective measures of compassion (i.e., as opposed to reliance on self-report inventories).

Discussion

A systematic evaluative review of LKM and CM intervention studies focusing on psychopathology-relevant outcomes was conducted. Over 65 % of the studies included in the review were published within the last 3 years, suggesting that clinical interest into LKM and CM is steadily increasing. The use of slightly broader inclusion criteria in the current review (i.e., greater range of study designs, adult and non-adult populations, etc.) meant that at least 50 % of the studies evaluated here were not included in the previous reviews of LKM and CM by either Hofmann et al. (2011) or Galante et al. (2014).

Taken as a collective, the findings of the studies reviewed here suggest that Buddhist-derived LKM and CM interventions may have applications in the prevention and/or treatment of a broad range of mental health issues including (but not limited to) (i) mood disorders, (ii) anxiety disorders, (iii) stress (including work-related stress), (iv) schizophrenia spectrum disorders, (v) emotional suppression (including suppressed empathic response), (vi) fear of self-compassion, and (vii) self-disparaging schemas. Findings also indicate that LKM and/or CM interventions may be acceptable to individuals of different age groups (i.e., adolescents, students, and adults), as well as clinical (including subclinical) and healthy populations. A further noteworthy observation is that it seems that LKM and CM techniques can be taught within a relatively short period of time—just a single 20-minute training session (followed by self-practice) in the case of the study by May et al. (2012). Outcomes from the included studies also indicate that salutary effects can be derived after attending weekly (or biweekly) sessions for periods of just 3–12 weeks.

No obvious benefits were identifiable for LKM versus CM techniques. However, in the study by Sears and Kraus (2009), the adjunctive practice of LKM with mindfulness meditation out-performed standalone LKM practice (based on outcomes of anxiety, negative affect, and hope). This finding appears to support the Buddhist operationalization of LKM and CM that are traditionally practiced as part of a comprehensive and multifaceted approach to meditation. Within Buddhism, the more passive and open-aspect attentional set engaged during mindfulness practice helps to build concentrative capacity and meditative stability (e.g., Dalai Lama 2001). This meditative stability acts as a platform for subsequently cultivating the more active or person-focused attentional set utilized during LKM or CM practice. Likewise, Buddhism asserts that effective mindfulness practice is reliant upon LKM and CM proficiency because a meditator cannot expect to establish full mindfulness of their thoughts, words, and deeds, without an in-depth awareness of how such actions will influence the well-being or suffering of others (Shonin et al. 2013b). This symbiotic relationship that exists between mindfulness and LKM/CM has also been identified in studies of mindfulness involving clinical populations where (for example) increases in compassion and self-compassion have been observed in patients with severe health anxiety (hypochondriasis) following treatment using Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (Williams et al. 2011).

Although numerous psychopathology-relevant variables were assessed in the reviewed studies, significant improvements were most frequently observed across the following five outcome domains: (i) positive and negative affect, (ii) psychological distress, (iii) positive thinking, (iv) interpersonal relations, and (v) empathic accuracy. From a mechanistic perspective, increased neural activity in brain areas such as the anterior insula, post-central gyrus, inferior parietal lobule (including the mirror-neuron system), amygdala, and right temporal-parietal junction has been shown to enhance regulation of neural emotional circuitry (Keysers 2011; Lutz et al. 2008). This improved regulatory capacity appears to have a direct effect on ability to modulate descending brain-to-spinal cord noxious neural inputs (Melzack 1991). This might explain why some patients/participants experience reductions in pain intensity and pain tolerance following LKM and/or CM practice.

In addition to mechanisms of a neurobiological nature, the increases in implicit and explicit affection towards others following LKM and CM has been shown to improve social connectedness and prosocial behavior (Hutcherson et al. 2008; Leiberg et al. 2011). In conjunction with the growth in spiritual awareness that can arise following LKM and CM practice, greater social connectedness can exert a protective influence over life stressors as well as feelings of loneliness, isolation, and low sense of purpose (Shonin et al. 2013c). Likewise, by encompassing the needs and suffering of others into their field of awareness, it appears that meditation practitioners are better able to add perspective to their own problems and suffering. According to Gilbert (2009), this more compassionate perspective can help to dismantle self-obsessed maladaptive cognitive structures and self-disparaging schemas. As individuals progress in their LKM and CM training and become less self-obsessed and more other-centred, findings from the current review suggest that these positive thinking patterns begin to undermine the tendency to engage in negative thought rumination—a known determinant of psychopathology (Davey 2008).

In addition to the obvious clinical applications and consistent with observations by Hofmann et al. (2011), findings from the current review also suggest that LKM and CM techniques may have utility in offender settings and/or for the treatment of anger control issues. Indeed, reductions in levels of anger were explicitly observed in Carson et al’s. (2005) LKM study with chronic lower back pain patients. Similarly, Hutcherson et al. (2008) demonstrated that practicing LKM for durations as short as 7 minutes can lead to greater levels of implicit and explicit positivity towards strangers. Proposals advocating the utilization of LKM and CM interventions in forensic settings (e.g., Shonin et al. 2013a) are consistent with the Buddhist view that a mind saturated with unconditional love and compassion is transformed of negative predilections and is incapable of (intentionally) causing harm (Dalai Lama 2001; Khyentse 2007).

Clinical Integration Issues

Issues that may impede the successful clinical integration of LKM and CM interventions are likely to be similar to the types of operational complications encountered as part of the (ongoing) roll-out of mindfulness-based interventions. The operationalization of mindfulness meditation has been hindered by difficulties in defining the mindfulness construct (Chiesa 2013), and it is probable that confusion in terms of what actually constitutes LKM and CM practice will generate similar problems. Indeed, although loving-kindness and compassion are traditionally regarded as two distinct constructs, several of the studies included in this systematic review utilized the two terms interchangeably. For example, in the intervention utilized by May et al. (2012) that the authors described as LKM, in addition to directing feelings of happiness towards a known other (i.e., a loving-kindness practice), participants were also instructed to cultivate the wish for others to “be free from suffering” (i.e., a compassion practice) (p. 3). Thus, from the information provided by the authors, rather than just LKM, it appears that participants were actually being instructed in both LKM and CM techniques. Although there is nothing wrong with combining LKM and CM techniques within a single intervention, different interpretations of Buddhist/meditational terminology leads to operational complications and obfuscates any comparisons that might be made between different intervention types.

In addition to issues arising from inconsistent delineations of LKM and CM, there are also issues that relate to the inclusion of mindfulness techniques as part of LKM and CM practice (and vice versa). For example, Johnson et al. (2009) describe LKM as a technique that “involves quiet contemplation, often with eyes closed or in a non-focused state and an initial attending to the present moment” (p. 503) in which participants are instructed to “non-judgementally redirect their attention to the feeling of loving-kindness when attention wandered” (p. 504). Based on such descriptions, it is difficult to discern where mindfulness practice ends and LKM (or CM) practice begins. Similarly, loving-kindness and mindfulness meditation techniques are often amalgamated together in the delivery of 8-week mindfulness-based interventions such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Van Gordon et al. 2013). Thus, there is a need to establish clear and accurate working definitions for LKM and CM that allow them to be clearly delineated from one another and from other Buddhist-derived meditation techniques more generally.

Other factors that may impede the integration of LKM and CM techniques as acceptable clinical interventions relate to the challenges of assimilating Eastern techniques into Western culture (see, for example, Lomas et al. 2014). Of particular bearing is the proficiency and training of LKM and CM instructors and trainers who may not have the experience to impart an embodied authentic transmission of the subtler aspects of meditation practice (Van Gordon et al. 2014a). Likewise, LKM and CM instructors that have not undergone extensive meditation training may not be appraised of the potential pitfalls of meditation that are alluded to throughout the traditional meditation literature. Examples of adverse effects traditionally associated with poorly administered meditation instruction are (i) asociality, (ii) nihilistic and/or defeatist outlooks, (iii) dependency on meditative bliss, (iv) a more generalized addiction to meditation, (v) engaging in compassionate activity beyond one’s spiritual capacity (and at the expense of psychological well-being), (vi) psychotic episodes, and (v) spiritual materialism (a form of self-deception in which rather than potentiating spiritual development and subduing selfish or egotistical tendencies, meditation practice serves only to increase ego-attachment and narcissistic behavior) (e.g., Chah 2011; Gampopa 1998; Shapiro 1992; Shonin et al. 2014d; Trungpa 2002; Tsong-Kha-pa 2004; Urgyen Rinpoche 1995).

A further clinical integration issue for LKM and CM interventions is the risk of compassion fatigue (i.e., due to patients “taking upon themselves” the suffering of others prematurely). This risk seems to be quite real when considered in light of some of the descriptions of 6-to-8-week-long LKM and CM interventions. For example, according to the description of CBCT as provided by several of the papers included in this review, “the meditation training culminates in the generation of active compassion: practices introduced to develop a determination to work actively to alleviate the suffering of others” (e.g., Desbordes et al. 2012, p. 5).

However, in the traditional Buddhist setting, prior to viscerally sharing others’ suffering (and acting unconditionally to ameliorate that suffering), meditation practitioners typically train for years-on-end in order to generate meditative and emotional equanimity within themselves, as well as a full awareness of the nature of their own suffering (Dalai Lama 2001; Urgyen Rinpoche 1995). Consistent with this Buddhist approach, studies involving trauma patients have shown that higher levels of self-compassion and mindfulness lead to reductions in post-traumatic avoidance strategies (e.g., Follette et al. 2006; Thompson and Waltz 2008). Thus, to encourage potentially emotionally unstable patients to “actively alleviate the suffering of others” after a total of just 16-hours meditation instruction (i.e., eight 2-hour sessions) could lead to deleterious outcomes. Caution, competence, and discernment are therefore required in the delivery of 3–12-week-long LKM and CM interventions.

Limitations of the Current Evidence Base

Although findings from the studies included in this systematic review attest to the clinical utility of LKM and CM interventions, a rating of moderate for the mean quality score (based on the QATQS assessment) of the included studies suggested that there were a number of design issues and limitations. Sample sizes across the 20 included studies were relatively small—an average of 66 participants were included in each study and in the case of 17 studies, these participants were distributed across two or more allocation conditions. Few of the studies assessed fidelity of implementation and therefore did not control for deviations from the intervention delivery plan. In a number of cases, participant adherence to practice data was not elicited which means that factors unrelated to participation in the LKM and/or CM intervention may have exerted a therapeutic influence and confounded the findings. A further limitation was an over-reliance on self-report measures that may have introduced errors due to recall bias and/or deliberate over or under reporting. Additional quality issues were the non-justification of sample sizes and poorly defined control conditions that did not account for non-specific factors. Furthermore, few of the studies included a follow-up assessment to evaluate maintenance effects.

Potentially limiting factors may also have been introduced by the eligibility criteria employed in the current systematic review. More specifically, only English language studies were included, which, given the popularity of Buddhist-derived meditation techniques in Eastern-language countries, may have resulted in the omission of relevant empirical evidence. Likewise, unpublished and non-peer-reviewed papers were not included in the review meaning that further potentially relevant evidence may have been disregarded.

Conclusions

From this systematic evaluative review, it is concluded that LKM and CM interventions may have utility for treating of a broad range of mental health issues in both clinical and healthy adult and non-adult populations. In particular, the empirical evidence suggests that LKM and CM can improve the following: (i) psychological distress, (ii) levels of positive and negative affect, (iii) the frequency and intensity of positive thoughts and emotions, (vi) interpersonal skills, and (v) empathic accuracy. However, there is a need for replication of these preliminary findings with larger sized samples and utilizing more methodologically robust study designs. In order to overcome operational issues that may impede the effective clinical integration of LKM and CM interventions, a lessons-learned approach is recommended whereby issues encountered as part of the (ongoing) rollout of mindfulness-based interventions are given due consideration. In particular, there is a need to establish accurate working definitions for LKM and CM that allow them to be clearly delineated from one another, and from other Buddhist-derived meditation techniques more generally.

References

Albertson, E. R., Neff, K. D., & Dill-Shackleford, K. E. (2014). Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: a randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0277-3.

American Psychiatric Association. (2010). American psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (3rd ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45.

Barnhofer, T., Chittka, T., Nightingale, H., Visser, C., & Crane, C. (2010). State effects of two forms of meditation on prefrontal EEG asymmetry in previously depressed individuals. Mindfulness, 1, 21–27.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 241–251.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897.

Blanchard, J. J., Kring, A. M., Horan, W. P., & Gur, R. (2011). Toward the next generation of negative symptom assessments: the collaboration to advance negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37, 291–299.

Bodhi, B. (1994). The noble eightfold path: way to the end of suffering. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Byock, I., & Merriman, M. (1998). Measuring quality of life for patients with terminal illness: the Missoula-VITAS quality of life index. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12, 231–244.

Carson, J. W., Keefe, F. J., Lynch, T. R., Carson, K. M., Goli, V., Fras, A. M., & Thorp, S. R. (2005). Loving-kindness meditation for chronic low back pain: results from a pilot trial. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23, 287–304.

Chah, A. (2011). The collected teachings of Ajahn Chah. Northumberland: Aruna Publications.

Chiesa, A. (2013). The difficulty of defining mindfulness: current thought and critical issues. Mindfulness, 4, 3255–3268.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24, 2125–2127.

Crane, C., Jandric, D., Barnhofer, T., & Williams, J. M. (2010). Dispositional mindfulness, meditation, and conditional goal setting. Mindfulness, 1, 204–214.

Dalai Lama (2001). Stages of meditation: training the mind for wisdom. London: Rider.

Davey, G. C. (2008). Psychopathology: research, assessment and treatment in clinical psychology. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.