Abstract

Adults with childhood onset conditions now have improved survival rates, and are experiencing health, medical, and performance issues related to their original conditions or treatments. The published science regarding the medical and performance issues of adults with cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and pediatric central nervous system cancer is increasing in quality, rigor, and clinical usefulness. This article is a systematized, focused review, with an appraisal of the literature, of these three conditions. Most of the published research is observational, from which recommendations can be made; however, there are few studies that demonstrate effective interventions. Although each of the three conditions has associated specific health and medical issues, they also have common problems and concerns related to health care, activity, performance, participation, and quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of published reports concerning aging and health conditions of adults with childhood onset disabilities has increased since the early 1990s, but does not approach the number of published articles concerning the effects of disabling conditions during childhood. Because the USA has few national registries or databases that follow health and care needs of these individuals, long-term epidemiological studies of these conditions are difficult. Despite the increase in the number of publications about aging with childhood disability, there continues to be limited education about this topic for health professionals, even for those within rehabilitation professions. In addition, few clinicians receive knowledge updates or new information on this subject, and are unaware of the quality or rigor of scientific reports they may have read to support management choices. Not surprisingly, adults with disabilities, including childhood onset disabilities, report a lack of knowledge by health care providers related to their health concerns and issues [1].

This article will review the most recent information (2008–2012), with a focus on determination of design level and rigor, related to three conditions commonly encountered by physiatrists within adult and pediatric practices. Cerebral palsy and spina bifida compose the largest portion of diagnoses seen by pediatric physiatrists and those adult physiatrists willing to evaluate patients with childhood onset disabilities. Typically, practitioners who work with adults with disabilities have a limited awareness of the descriptive and observational reports regarding lifelong disability issues. Childhood cancer survivors, especially brain tumor survivors, are increasing in prevalence, and there are now more observational reports using national registries identifying longer-term issues these adults now face. Although physiatrists are not particularly engaged with this population at present, health and function-related conditions of these adults seem well suited to physiatric specialty care.

Methods

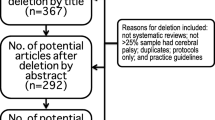

We have chosen to base our review of these topics on a rigorous formal quality appraisal review [2] of the literature from 2008 to 2012 to better help clinicians understand the significance of the science at present, which increasingly informs practice and evaluation of practitioners. In general, a comprehensive MEDLINE search was undertaken for each condition (cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and childhood or pediatric brain tumor) using that term then “adult” and/or “aging,” and then combining the results. Inclusion criteria were English language and publication year of 2008 forward. A gray literature search was also completed using Google and Google Scholar for each topic for relevant outcomes or observational research, again with limits of English language and publication year of 2008 forward.

Each article title and/or abstract was then initially reviewed to ensure the article represented observational, interventional, or review (with quality appraisal) research, and adults were represented in the article or adults were reported separately if comparisons were made with children or controls. Each article meeting that criterion was then reviewed fully, data were collected about the study design and outcomes, and the article was then rated according to “Reading the Medical Literature” (http://www.acog.org/Resources_And_Publications/Department_Publications/Reading_the_Medical_Literature) of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (with addition of reviews noting quality of evidence).Footnote 1 with an additional evaluation of rigor for the observational studies (since these were the most prevalent) using the STROBE statement on observational studies [3], identified by eight key items.Footnote 2 Qualitative research was assessed using a hierarchy of evidence approach [4].Footnote 3 No commentaries, editorials, single case or case series reports, expert opinion, narrative reviews without quality assessment, or other articles of this type or of similar quality were included. There was crossover of the review process on all topics by the three authors to ensure consistency, with two authors involved for each topic; any discrepancies were decided by consensus. Descriptive tables were developed for articles fully reviewed and identified as level I or II; observational studies have the negative rigor ratings identified.

Results

In general, there were only a limited number of articles that were related to adults with these three conditions, and even fewer of methodological quality to be included in this report. Most of the articles concerned cerebral palsy. Most of the studies reported are observational, and most have a cross-sectional design, except those concerning pediatric cancers benefiting from registries; limitations in research were acknowledged, and most often related to small sample sizes, biases, differing levels of severity among subjects, and unvalidated measurement tools. Comparison of studies was limited since a variety of instruments were used. Case series describing outcomes from specific practices or regions and traditional literature reviews without literature appraisal, although serving a purpose for education and dissemination, are not included since their evidence level is rated low. We felt it was important to clearly identify the state of the science.

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy is a common diagnosis treated by physiatrists for rehabilitation or other health or functionally directed interventions to manage health and activity. Increasingly, it is recognized that function and health may change for adults with cerebral palsy over time and that there is a need for acknowledgement, recognition, and prevention (when possible) of issues related to aging [5].

The comprehensive MEDLINE search used the term “cerebral palsy” then “aging,” “adult,” and “pain” separately; each secondary term was separately combined with “cerebral palsy.” A total of 1,294 articles underwent title/abstract review, and 60 underwent more thorough review. Through a search of the gray literature using “cerebral palsy” and ”adult,” an additional 19 articles were identified. A total of 28 articles were of sufficient level of evidence and rigor for presentation, and are noted in Table 1.

Health and Health Care

A survival rate of 80 % for individuals with cerebral palsy to age 40 years and highest mortality under the age of 15 years is supported by a recent Australian registry study that confirms previous work. Predictors for mortality are strongly related to severity, especially “not walking” [6]. Additional health conditions are now better described:

-

1.

Dental care has improved in recent years, and in Germany, where vigilant care is well provided, adults with cerebral palsy have similar recognition of dentition irregularities when compared with the German general public [7].

-

2.

Swallowing changes are noted by adults with cerebral palsy with aging, in some as young as 30 years old. These changes with their subsequent dining modifications (with little involvement of the adults themselves in decision-making) engendered negative emotional responses [8].

-

3.

Cervical myelopathy is associated with age (more than 36 years) and severity of neck dystonia, with the best clinical clues being gait changes/falls, hand muscle wasting, and changes in urinary function [9]; Guettard et al. [9] recommend screening beginning in the third decade.

There are now consistent reports of unmet health care needs for young adults with cerebral palsy. As has been reported in other studies of adults with disabilities, young adults with cerebral palsy have reported difficulties receiving information about lifelong health, mobility problems, and access to care, despite having seen providers (including rehabilitation physicians and physical therapists) routinely [10].

Pain

Pain continues to be commonly reported by adults (and children) with cerebral palsy [11]. Common areas of pain complaint are the back, legs, and neck. The number of pain sites increases with age. Many interventions are offered, although they are of modest to minimal effect, and no single provider type offers the best support [11–13]. A single uncontrolled interventional study suggested use of a backpack to improve back pain, but the effect proved to be only modest and over a short time [14]. Chronic pain and fatigue, and to a lesser extent depression, compose a complex set of interdependent factors that affect the performance of adults with cerebral palsy and may be unrelated to level of function [15, 16]. Activity and physical therapy modalities most consistently provide some level of improvement [12, 13]. However, chronic pain with or without fatigue does not affect daily function or psychological health, unlike in the general population, which reports decreased physical and mental health with pain [13, 15]. There is no new guidance on pain management other than a reiteration that pain symptoms may be expected, and should be identified, evaluated, and treated, even at younger ages. Adults with lifelong disabilities appear to have some accommodation of chronic conditions, however the pain–fatigue (and possibly depression) complex has yet to be unraveled.

Activity/Performance

Activity is generally decreased in adults with cerebral palsy, although fitness has no relationship to physical activity or fatigue [17, 18]. Activity is well below the general activity recommendations to promote health and wellness [19]. A higher Gross Motor Function Classification System level (severer motor impairment) is associated with lower activity and performance. There is moderate evidence that muscular strength is a component for lower fitness in cerebral palsy, with more limited evidence that muscular and cardiorespiratory endurance contribute to lower fitness; there is no good evidence related to flexibility and body composition in cerebral palsy [20]. Therefore, although activity levels are important, there are no clear directions to improve physical activity for adults with cerebral palsy.

A closer look at interventions and targets of interventions to improve performance reveals (1) balance measurement instruments do not seem to be correlated to deterioration in walking abilities [21], and not surprisingly, postural responses and adjustments seem to relate more to changes in walking, and (2) a novel upper limb program, using a computer/Web-based training and measurement system, can improve function, although long-term effectiveness has not been determined [22].

Participation

As expected, adults with cerebral palsy face difficulties engaging in social activities such as employment, recreation and leisure activities, and preparing meals, have limited access to transportation, and have limited dating and romantic experiences [23–26]. Higher severity may be related to lower employment: lower IQ and a need for transportation assistance (along with female gender) accounted for low employment in a mixed-methods study with adults with cerebral palsy and spina bifida [23]. However, there are opposing views regarding socialization; less socialization is reported with higher Gross Motor Function Classification System and Manual Ability Classification System category [24]; however, social functioning and support, friendships, and romantic experiences may have no associations with severity [19, 25]. The relationship of these social activities with health-related quality of life is also not clear [19, 26], and these conflicting reports may be related to differences in locales, available support, levels of function of the study participants, and the variety of measurements used. There is a further suggestion that self-efficacy, effort or perseverance, or adaptation may account for differing responses to barriers to socialization. This concept of resiliency continues to be elusive.

Basic Science

In the spirit of promoting interventional research, there is now standardization of routine measurements for adults with cerebral palsy. Many of these measures have been used in past research, and use of them (net Vo 2 6-min walk test, strength measurement, predicted Vo 2max, Manual Ability Classification System) was reported as a limitation of design and outcome interpretation [27–30]. More research is being directed at muscle parameters in cerebral palsy, possibly to better focus interventions. A single study measured muscle volume and concentric muscle work during walking to evaluate the value of a strengthening program; however, it was unable to identify exactly on which muscle groups a strengthening program should be focused to improve gait. However, the identified increased bilateral hip extensor work in hemiplegia demonstrated the importance of proximal strengthening [31].

Spina Bifida

There has been a significant increase in interest about the health and quality of life of adults with spina bifida, although the number of publications remains less than that for adults with cerebral palsy. Medical and surgical advances developed in the 1960s have now provided the first relatively large cohort of adults, who in some cases demonstrated unique health and aging issues.

A comprehensive MEDLINE search using the term “spina bifida” then “adult” and combining the results was completed. Forty-six articles were retrieved using this method; a gray literature search using the terms “spina bifida” and “adult” identified an additional 41 unique articles and proceedings. Fourteen articles met all the criteria and are included in Table 2.

Health and Health Care

A number of reviews or case series reports from clinics for adults with spina bifida have been published in the past 5 years [32–35], with neurosurgical, urological, musculoskeletal, and cardiopulmonary issues identified which demand specialty care beyond that of a typical primary care provider. A number of additional medical issues have emerged as well. Obesity appears to be a significant concern in adults, with rates in the 37 % range [36, 37]. However, sadly this is not greatly different from the 35 % for the general adult US population reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/facts.html). Cardiovascular disease risk factors were reported in a Dutch sample, with 42 % of adolescents and young adults with spina bifida at increased risk, and of those, 61 % were nonambulatory [38]. Increased risk was not associated with physical activity or body fat. Lymphedema frequency was reported by a single study as nearly 100 times the rate of that in the general population [37]. It was associated with trauma, cellulitis, cancer, obesity, wounds, hypertension (38.3 %), level of lesion, and mobility status. Increased number of skin ulcers was associated with higher motor level and higher educational level in one study [39]. Higher number of hospitalizations was associated with the number of wounds and lower self-management scores [39].

As in adults with cerebral palsy, pain was noted in a health-related quality of life survey more frequently in young adults than in youths [40]. High rates of depression, anxiety, and pain were found and were closely related to attitude and family functioning [41]. Similarly, Soe et al. [42] found that nearly half of the subjects studied reported depressive symptoms.

Researchers have addressed health promotion through descriptions of health risks. In general, physical activity is decreased in adults with spina bifida [38, 42], and walking was noted to decrease as adults aged [40]. Less healthy diets, less exercise, and more sedentary behaviors were reported in young adults with spina bifida, with a peak in substance abuse in their late 20s [42]. Self-management and early detection of wounds and urinary tract infections are suggested to decrease the incidence of complications [39], although no specific recommendations were offered. O’Mahar et al. [43] described a novel intervention targeting independence and self-management through a camp experience. Through goal identification and group session activities, campers and parents noted improvement in personal management and social goals, and to a lesser extent in taking responsibility and being independent with self-management tasks at the end of the period. Both studies acknowledged the need for approaches specifically focused on the cognitive needs of people with spina bifida.

Cognition

Cognitive changes are suspected earlier with aging and spina bifida. Many young adults with spina bifida demonstrate decreased executive function abilities [44]. In a comparison study of adults with and without spina bifida, memory problems were found at a younger age as well as less use of compensatory strategies, with no correlation of poorer memory with shunt history [45]. Upper extremity dexterity may be compromised in adults with spina bifida, particularly when distractions are present, which has implications for rehabilitation and eventual successful employment [46]. Treble et al. [47] looked at the effect of cortical thickness (measured by MRI) on IQ and fine motor dexterity in typically developing people and individuals with spina bifida. The more the thickness and level of gyrification deviated from typical (increased or decreased), the more impaired the subjects were on testing.

Participation

Most young adults with spina bifida do not live independently, have low rates of employment, and are less likely to have romantic relationships. A longitudinal study following the transition from adolescence to adulthood for youths with and without spina bifida noted that youths with spina bifida have difficulty achieving adult milestones within the same time period as their peers. Typically developing subjects were more likely to leave home, attend college, become employed, and develop social relationships. When high school graduates were compared, there was no statistically significant difference except in romantic relationships, where development of romantic relationships for people with spina bifida was delayed. Youths with greater executive functioning are more likely to be successful [44]. Virtual socialization may contribute to the number of friends one identifies, but it does not affect quality of life [48].

As noted for cerebral palsy, 46 % of a sample of young adults with cerebral palsy and spina bifida were not employed, which was related to gender, cognitive scores, and transportation dependence. Qualitative themes in data analysis concerned transportation barriers, social reactions to disability, inability to advance within the job market, and employment programs that did not meet needs [23]. A further qualitative study was done with the same participants, and although transportation continued to be a roadblock, individualization and flexibility of services over time emerged as key requirements for effective support for people with disabilities [49].

Although more information describing the limitations is available, specific recommendations have been offered about interventions or support to improve levels of social participation.

Childhood Onset Brain Cancer Survivors

Advances in childhood cancer treatment have increased the number of survivors into adulthood, and with that, there has been increasing interest in the long-term health of survivors and late effects of their cancer treatments. Many countries, including the USA, have established registries to allow long-term follow-up. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/coping/ccss), funded through the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health, monitors survivors (and siblings) originally diagnosed more than 30 years ago by cohorts, and involves more than 20 US and Canadian centers.

As for the two previous conditions, a comprehensive MEDLINE search was completed from 2008 to 2012 using the term “childhood cancer” then “brain tumor” and then “adult” and “survivor” for a combined total of 86 articles. A gray literature search using “childhood CNS (central nervous system) cancer” and “survivor” found an additional 25 articles. Additional inclusion criteria were applied to focus on rehabilitation-related articles. Seventy articles were found; 15 met the detailed review criteria for reporting here, and are reported in Table 3.

Health and Health Care

Survival of childhood central nervous system (CNS) cancers has high risk of late mortality beyond 5 years, and survivors are noted to have late effects or secondary conditions related to neurologic, sensory (especially auditory), endocrine, and musculoskeletal systems [50, 51]. Additionally there is an increased risk, compared with a general population of siblings, of developing other neoplasms, especially second primary brain tumors [50, 52]. The incidence of neurocognitive impairments is high, and they relate to radiation doses and sites of radiation therapy [50, 53]. Physical performance is limited for adult survivors of childhood brain tumors as noted in a cross-sectional study [54]; in particular, survivors of medulloblastoma and osteosarcoma had the highest rates of inactivity, and cranial radiation therapy, amputation, female gender, black race, older age, lower educational attainment, extremes of weight, smoking, and depression had high associations with inactivity [55]. Muscle strength and fitness values for the survivors were similar to standard and comparative values for individuals aged 60 years or older, with limited physical performance and poorer management of home and school activities. Survivors of CNS tumors are at risk of obesity, inactivity, and an increasing number of chronic conditions [56]. Natural target areas for rehabilitation activities would be within the realms of activity level, weight management, and performance. Adult survivors often maintain their follow-up services within pediatric center delivery networks [57, 58]; although this was a preference for some survivors, a number of barriers were noted in maintaining that activity.

Cognitive and Psychological Issues

Cognitive impairments are common, and pediatric oncology centers often include neuropsychologic testing in their routine follow-up. The tool used within the US registry studies, the Neurocognitive Questionnaire, has been standardized for this population [59]. Through the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study network, associations have been found among radiation dosing, site of radiation therapy, neurocognitive issues, and social participation; exposure of temporal brain regions to radiation is related to increased risk of memory and social functioning impairments and general health problems, whereas frontal brain exposure is associated with physical performance and general health problems [53]. Additional factors (e.g., shunt placement, gender, and diagnosis before 2 years) are implicated in affecting cognitive function [60]. Survivors of pediatric leukemia and CNS tumors are at higher risk of depression and anxiety, attention deficits, oppositional behavior, and social withdrawal than individuals with other pediatric cancer diagnoses [56].

Participation

As cancer survivors age, there is a need for monitoring of long-term social consequences of tumors and treatment. A registry survey study from the UK has documented that survivors of childhood cancers are at a higher risk of lower educational attainment with cranial radiation therapy, CNS tumor diagnosis, older age at completion of the questionnaire, younger age at diagnosis, having epilepsy, and being female [61]. Again, cranial radiation therapy has been found to be associated with higher unemployment rates [62]. Pronounced reductions in marriage/cohabitation are seen in survivors of CNS tumors [63]. Adult survivors of pediatric brain tumors tended to limit their participation and interaction with the environment, which is associated with reduced health-related quality of life [64]. In general, low physical and cognitive performance, and less social participation, is common for adult survivors of pediatric onset CNS cancer. Many recommendations to facilitate social and performance success are offered within these publications that involve rehabilitation and physiatric strategies, although there have been no controlled interventional studies to show effectiveness.

Models of Transitional Care

Health care transition is a topic of interest for individuals with complex care needs and their care providers, and deserves a separate section. Although there is much interest in this topic in the literature, there is very little evidence to define the key components, evaluation structure, or outcomes of such programs. There are publications discussing this theme for all three childhood onset conditions. A qualitative study with a small group of adults with a variety of childhood onset disabilities identified challenges to transition of care—lack of access to health care, lack of professionals’ knowledge, lack of information regarding the transition process—and offered the solutions of providing early detailed information about and extensive support for the process [65]. Two review articles about health care transitions for adolescents with complex medical needs note there is inconclusive evidence about key components for transition programs and what constitutes effective transitional care [66, 67]. A survey of long-term follow-up programs in the USA for survivors of childhood brain tumors noted considerable variations in services and organization across the country. Additionally, the survey offered barriers to establishment of programs: lack of insurance, lack of funding or dedicated time for professionals, patients’ uncertainties about the need for follow-up, and patients’ desire not to be followed in a pediatric program [57]. Transition programs may theoretically make sense and consumers may report high satisfaction conceptually, but there are no clear guidelines or outcome studies to promote their implementation.

Conclusion

Survival of people with these three childhood onset conditions into adulthood has enabled cohort studies of associated health and performance issues. Although these reports have increased in quality and rigor, especially when national registries or networks are available, most are observational, and there is little interventional research. Some of the reported studies have validated established measures for these special populations. The availability of these tools should facilitate future interventional studies.

Health providers should anticipate secondary conditions/late effects, and health risks for each condition. Adults with childhood onset disability require increased complexity of services and specialized understanding by providers. Current published information shows that there are many commonalities among these three conditions. These consumers are requesting more information from their health care providers and many are seeking participation in care decisions. Low levels of activity, performance, and participation are prevalent, and they may relate to the severity of the impairment. Observational studies often recommend improved accessible exercise opportunities, and more self-management, cognitive rehabilitation, pain management, and health promotion programs. These resources are, of course, key components of comprehensive rehabilitation, and consumers, advocacy groups, and practitioners now recognize the usefulness of physiatric and rehabilitation strategies. These suggested interventions await further rigorous research to demonstrate effectiveness.

Several key concepts remain elusive, despite the many observational studies. What are the relationships among chronic pain, fatigue, and mood? What role does resiliency and self-efficacy play in long-term outcome, and can resiliency be taught or modeled? What are the relationships among cognitive impairments, “motivation,” and self-efficacy? How can exercise influence fitness, fatigue, pain, and performance over a lifetime with a disability? What strategies are useful to modify present activity and social outcomes? Although we have ever more information, much research remains to be done.

Disclosure

M.A. Turk’s institution has received a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1U01DD001007-01); L.R. Logan declares no conflict of interest; and F. Ansoanuur declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

Interventional studies: level I evidence randomized controlled trials; level II-1 evidence controlled trials. Observational studies: level II-2 evidence cohort and case–control studies; level II-3 evidence cross-sectional studies; level III evidence descriptive studies (case series, expert opinion). Other study designs: meta-analysis; decision analysis—modification to include systematic or other quality assessment reviews.

STROBE items rated yes/no include Methods (setting, participants, variables, data sources, and statistical methods) and “Discussion” (key results, limitations, and interpretation).

Level I generalizable studies (methodologic sampling, analysis); level II conceptual studies (theoretical sampling, methodologic analysis); level III descriptive studies (practical sampling); level IV single case study (views of one subject).

References

Iezzoni LI, Long-Bellil LM. Training physicians about caring for persons with disabilities: “nothing about us without us!”. Disabil Health J. 2012;5(3):136–9.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):800–4.

Daly J, Willis K, Small R, Green J, Welch N, Kealy M, et al. A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):43–9.

Tosi LL, Aisen ML. Special issue: adults with cerebral palsy: a workshop to define the challenges of treating and preventing the secondary musculoskeletal and neuromuscular complications in this rapidly growing population. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(Suppl 4):1–184.

Reid SM, Carlin JB, Reddihough DS. Survival of individuals with cerebral palsy born in Victoria, Australia, between 1970 and 2004. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(4):353–60.

Asdaghi Mamaghani SM, Bode H, Ehmer U. Orofacial findings in conjunction with infantile cerebral paralysis in adults of two different age groups: a cross-sectional study. J Orofac Orthop 2008; 69(4):240–56.

Balandin S, Hemsley B, Hanley L, Sheppard JJ. Understanding mealtime changes for adults with cerebral palsy and the implications for support services. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(3):197–206.

Guettard E, Ricard D, Roze E, Elbaz A, Anheim M, Thobois S, et al. Risk factors for spinal cord lesions in dystonic cerebral palsy and generalised dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(2):159–63.

Nieuwenhuijsen C, van der Laar Y, Donkervoort M, Nieuwstraten W, Roebroeck ME, Stam HJ. Unmet needs and health care utilization in young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(17):1254–62.

Riquelme I, Cifre I, Montoya P. Age-related changes of pain experience in cerebral palsy and healthy individuals. Pain Med. 2011;12(4):535–45.

Hirsh AT, Kratz AL, Engel JM, Jensen MP. Survey results of pain treatments in adults with cerebral palsy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(3):207–16.

Opheim A, Jahnsen R, Olsson E, Stanghelle JK. Physical and mental components of health-related quality of life and musculoskeletal pain sites over seven years in adults with spastic cerebral palsy. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(5):382–7.

Lai ES, Chow DK, Tsang VN, Tsui SS, Lam CY, Su IY, et al. Effect of load carriage on chronic low back pain in adults with cerebral palsy. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2011;35(4):439–44.

Van Der Slot WM, Nieuwenhuijsen C, Van Den Berg-Emons RJ, Bergen MP, Hilberink SR, Stam HJ, et al. Chronic pain, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in adults with spastic bilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(9):836–42.

Malone LA, Vogtle LK. Pain and fatigue consistency in adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(5):385–91.

Nieuwenhuijsen C, van der Slot WM, Beelen A, Arendzen JH, Roebroeck ME, Stam HJ, et al. Inactive lifestyle in adults with bilateral spastic cerebral palsy. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(5):375–81.

Nieuwenhuijsen C, van der Slot WM, Dallmeijer AJ, Janssens PJ, Stam HJ, Roebroeck ME, et al. Physical fitness, everyday physical activity, and fatigue in ambulatory adults with bilateral spastic cerebral palsy. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(4):535–42.

Gaskin CJ, Morris T. Physical activity, health-related quality of life, and psychosocial functioning of adults with cerebral palsy. J Phys Activity Health. 2008;5(1):146–57.

Hombergen SP, Huisstede BM, Streur MF, Stam HJ, Slaman J, Bussmann JB, et al. Impact of cerebral palsy on health-related physical fitness in adults: systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(5):871–81.

Opheim A, Jahnsen R, Olsson E, Stanghelle JK. Balance in relation to walking deterioration in adults with spastic bilateral cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 2012;92(2):279–88.

Brown SH, Lewis CA, McCarthy JM, Doyle ST, Hurvitz EA. The effects of Internet-based home training on upper limb function in adults with cerebral palsy. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010; 24(6):575–583.

Magill-Evans J, Galambos N, Darrah J, Nickerson C. Predictors of employment for young adults with developmental motor disabilities. Work. 2008;31(4):433–42.

Nieuwenhuijsen C, Donkervoort M, Nieuwstraten W, Stam HJ, Roebroeck ME. Transition Research Group South West Netherlands. Experienced problems of young adults with cerebral palsy: targets for rehabilitation care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):1891–7.

Wiegerink DJ, Roebroeck ME, van der Slot WM, Stam HJ, Cohen-Kettenis PT. South West Netherlands Transition Research Group. Importance of peers and dating in the development of romantic relationships and sexual activity of young adults with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(6):576–82.

van der Slot WM, Nieuwenhuijsen C, van den Berg-Emons RJ, Wensink-Boonstra AE, Stam HJ, Roebroeck ME, et al. Participation and health-related quality of life in adults with spastic bilateral cerebral palsy and the role of self-efficacy. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(6):528–35.

Maltais DB, Robitaille NM, Dumas F, Boucher N, Richards CL. Measuring steady-state oxygen uptake during the 6-min walk test in adults with cerebral palsy: feasibility and construct validity. Int J Rehabil Res. 2012;35(2):181–3.

De Groot S, Janssen TW, Evers M, Van der Luijt P, Nienhuys KN, Dallmeijer AJ. Feasibility and reliability of measuring strength, sprint power, and aerobic capacity in athletes and non-athletes with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(7):647–53.

Satonaka A, Suzuki N, Kawamura M. Validity of submaximal exercise testing in adults with athetospastic cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(3):485–9.

van Meeteren J, Roebroeck ME, Celen E, Donkervoort M, Stam HJ. Transition Research Group South West Netherlands. Functional activities of the upper extremity of young adults with cerebral palsy: a limiting factor for participation? Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(5):387–95.

Riad J, Modlesky CM, Gutierrez-Farewik EM, Brostrom E. Are muscle volume differences related to concentric muscle work during walking in spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy? Clin Orthop. 2012;470(5):1278–85.

Dicianno BE, Kurowski BG, Yang JM, Chancellor MB, Bejjani GK, Fairman AD, et al. Rehabilitation and medical management of the adult with spina bifida. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(12):1027–50.

Rekate HL. The pediatric neurosurgical patient: the challenge of growing up. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2009;16(1):2–8.

West C, Brodie L, Dicker J, Steinbeck K. Development of health support services for adults with spina bifida. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(23–24):2381–8.

Webb TS. Optimizing health care for adults with spina bifida. Develop Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16(1):76–81.

Dosa NP, Foley JT, Eckrich M, Woodall-Ruff D, Liptak GS. Obesity across the lifespan among persons with spina bifida. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(11):914–20.

Garcia AM, Dicianno BE. The frequency of lymphedema in an adult spina bifida population. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(2):89–96.

Buffart LM, van den Berg-Emons RJ, Burdorf A, Janssen WG, Stam HJ, Roebroeck ME. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and the relationships with physical activity, aerobic fitness, and body fat in adolescents and young adults with myelomeningocele. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(11):2167–73.

Mahmood D, Dicianno B, Bellin M. Self-management, preventable conditions and assessment of care among young adults with myelomeningocele. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(6):861–865.

Young NL, Sheridan K, Burke TA, Mukherjee S, McCormick A. Health outcomes among youths and adults with spina bifida. J Pediatr. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.042

Bellin MH, Zabel TA, Dicianno BE, Levey E, Garver K, Linroth R, et al. Correlates of depressive and anxiety symptoms in young adults with spina bifida. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(7):778–89.

Soe MM, Swanson ME, Bolen JC, Thibadeau JK, Johnson N. Health risk behaviors among young adults with spina bifida. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(11):1057–64.

O’Mahar K, Holmbeck GN, Jandasek B, Zukerman J. A camp-based intervention targeting independence among individuals with spina bifida. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(8):848–56.

Zukerman JM, Devine KA, Holmbeck GN. Adolescent predictors of emerging adulthood milestones in youth with spina bifida. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(3):265–76.

Dennis M, Nelson R, Jewell D, Fletcher JM. Prospective memory in adults with spina bifida. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26(12):1749–55.

Dennis M, Salman MS, Jewell D, Hetherington R, Spiegler BJ, MacGregor DL, et al. Upper limb motor function in young adults with spina bifida and hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25(11):1447–53.

Treble A, Juranek J, Stuebing KK, Dennis M, Fletcher JM. Functional significance of atypical cortical organization in spina bifida myelomeningocele: relations of cortical thickness and gyrification with IQ and fine motor dexterity. Cereb Cortex. 2012. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhs226.

Chan WM, Dicianno BE. Virtual socialization in adults with spina bifida. PM R. 2011;3(3):219–25.

Darrah J, Magill-Evans J, Galambos NL. Community services for young adults with motor disabilities: a paradox. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(3):223–9.

Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Huang S, Ness KK, Leisenring W, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(13):946–58.

Whelan K, Stratton K, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, Hayashi S, Waterbor J, et al. Auditory complications in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(1):126–34.

Taylor AJ, Frobisher C, Ellison DW, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Taylor RE, et al. Survival after second primary neoplasms of the brain or spinal cord in survivors of childhood cancer: results from the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(34):5781–7.

Armstrong GT, Jain N, Liu W, Merchant TE, Stovall M, Srivastava DK, et al. Region-specific radiotherapy and neuropsychological outcomes in adult survivors of childhood CNS malignancies. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(11):1173–86.

Ness KK, Morris EB, Nolan VG, Howell CR, Gilchrist LS, Stovall M, et al. Physical performance limitations among adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Cancer. 2010;116(12):3034–44.

Ness KK, Leisenring WM, Huang S, Hudson MM, Gurney JG, Whelan K, et al. Predictors of inactive lifestyle among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2009;115(9):1984–94.

Krull KR, Huang S, Gurney JG, Klosky JL, Leisenring W, Termuhlen A, et al. Adolescent behavior and adult health status in childhood cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(3):210–7.

Bowers DC, Adhikari S, El-Khashab YM, Gargan L, Oeffinger KC. Survey of long-term follow-up programs in the United States for survivors of childhood brain tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(7):1295–301.

Ishida Y, Ozono S, Maeda N, Okamura J, Asami K, Iwai T, et al. Medical visits of childhood cancer survivors in Japan: a cross-sectional survey. Pediatr Int. 2011;53(3):291–9.

Krull KR, Gioia G, Ness KK, Ellenberg L, Recklitis C, Leisenring W, et al. Reliability and validity of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Neurocognitive Questionnaire. Cancer. 2008;113(8):2188–97.

Ellenberg L, Liu Q, Gioia G, Yasui Y, Packer RJ, Mertens A, et al. Neurocognitive status in long-term survivors of childhood CNS malignancies: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(6):705–17.

Lancashire ER, Frobisher C, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Glaser A, Hawkins MM. Educational attainment among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain: a population-based cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(4):254–70.

Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, Ness KK, Friedman DL, Armstrong GT, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Med Care. 2010;48(11):1015–25.

Koch SV, Kejs AM, Engholm G, Moller H, Johansen C, Schmiegelow K. Marriage and divorce among childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(7):500–5.

Brinkman TM, Li K, Neglia JP, Gajjar A, Klosky JL, Allgood R, et al. Restrcited access to the environment and quality of life in adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2013;111(2):195.

Young NL, Barden WS, Mills WA, Burke TA, Law M, Boydell K. Transition to adult-oriented health care: perspectives of youth and adults with complex physical disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2009;29(4):345–61.

Bloom SR, Kuhlthau K, van Cleave J, Knapp AA, Newacheck P, Perrin JM. Health care transition for youth with special health care needs. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):213.

Watson R, Parr JR, Joyce C, May C, Le Couteur AS. Models of transitional care for young people with complex health needs: a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(6):780–91.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turk, M.A., Logan, L.R. & Ansoanuur, F. Adults with Childhood Onset Disabilities: A Focused Review of Three Conditions. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 1, 72–87 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-013-0012-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-013-0012-3