Abstract

Background

Despite the high prevalence of depression, information about the burden of this disease in Switzerland is scarce. A better knowledge of the costs of depression may provide important information for future national preventive programmes, optimizing cost-effective budgeting. The estimates of national costs may improve the public’s awareness of depression and depression-related costs, breaking down the taboo of depression as an illness.

Objectives

The aims of this study were to analyse the annual cost for different levels of depression and to investigate the annual economic burden of depression in Switzerland.

Methods

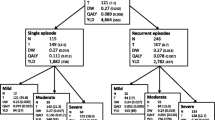

A retrospective, multicentre, non-interventional study in psychiatrist practices was carried out. Outpatients who had been diagnosed with depression in the last 3 years were included. Patient demographics and information on clinical characteristics and resource utilization in the first 12 months after diagnosis were collected. Costs analysis, subdivided into direct and indirect costs, was performed for three depression severity classes (mild, moderate and severe), according to the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17). Costs were also extrapolated to a national level. Regression analysis was performed to control for factors that may have an impact on the cost of depression.

Results

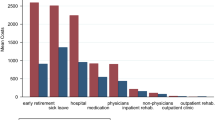

A total of 556 patients were included. Hospitalization and hospitalization days were directly correlated with disease severity (p < 0.001). Medical resource utilization linked to depression and antidepressant treatments was also correlated to the disease status. Severely depressed patients reported a significantly higher number of workdays lost and were significantly more often on disability insurance. The mean total direct costs per person per year, mainly due to hospitalization costs, were €3,561 for mild, €9,744 for moderate and €16,240 for severe depression. The mean indirect costs per person per year, mainly due to workdays lost, were €8,730 for mild, €12,675 for moderate and €16,669 for severe depression (year 2007/2008 values). Regression analysis showed that hospitalization days, psychiatrist visits in hospital, disability insurance, workdays lost and the HDRS-17 score were significantly correlated to the total costs. Extrapolation at a national level resulted in a total burden of about €8.1–8.3 billion per year.

Conclusions

The burden of depression in Switzerland was estimated to be about €8 billion per year. The costs of depression were directly related to disease severity. However, since many cases of depression remain unreported and since this analysis only included individuals between 18 and 65 years of age, it is reasonable to suppose that the total burden of depression may be even higher.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. Depression [fact sheet no. 369]. Geneva: WHO; 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/index.html. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-TR. Arlington: APA; 2012. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm-iv-tr. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD). http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

Pedersen SH, Stage KB, Bertelsen A, et al. ICD-10 criteria for depression in general practice. J Affect Disord. 2001;65(2):191–4.

Ajdacic-Gross V, Graf M. Bestandesaufnahme und Daten zur psychiatrischen Epidemiologie – Informationen über die Schweiz. Neuchatel: Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium; 2003.

Schuler D, Rüesch P, Weiss C. Psychische Gesundheit in der Schweiz—Monitoring. Neuchatel: Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium; 2007.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). Mortality, causes of death—data, indicators. Deaths: numbers, trends and causes. 2010 [in German]. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2013. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/14/02/04/key/01.html. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:37.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). Nachhaltige Entwicklung— MONET: Lebensbedingungen—Suizidrate. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2013. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/21/02/ind32.indicator.70301.3201.html. Accessed 17 Jan 2013.

Eurostat. Death due to suicide, by sex: standardised death rate by 100 000. Inhabitants. Luxembourg: European Commission, Eurostat; 2012. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/refreshTableAction.do?tab=table&plugin=0&pcode=tps00122&language=en. Accessed 17 Jan 2013.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO), Ärztliche Behandlung: Depression. Schweizerische Gesundheitsbefragung. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/14/02/01/key/02.html. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Nationale Gesundheitspolitik Schweiz (NGP), Psychische Gesundheit—Strategieentwurf zum Schutz, zur Förderung, Erhaltung und Wiederherstellung der psychischen Gesundheit der Bevölkerung in der Schweiz. Bern: BAG; 2004. http://www.bag.admin.ch/themen/medizin/00683/01916/. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

Beeler I, Lorenz S, Szucs TD. Provision and remuneration of psychotherapeutic services in Switzerland. Sozial und Praventivmedizin. 2003;48(2):88–96.

Gabriel P, Liimatainen M. Mental health in the workplace. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2000.

Lachenmeier H. Mental health—Ein Wirtschaftsfaktor. Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 6. Febr. 2003, Nr. 30, p. 14. http://www.synapse-online.ch/uploads/media/2003-3.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2013.

Andlin-Sobocki P, Jonsson B, Wittchen HU, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(Suppl 1):1–27.

Jäger M, Sobocki P, Rossler W. Cost of disorders of the brain in Switzerland with a focus on mental disorders. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138(1–2):4–11.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch General Psychiatry. 1988;45(8):742–7.

Hamilton M. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17-item version). Castres: NeuroBiz Consulting; 2008. http://www.psy-world.com/hdrs.htm. Accessed 17 Jan 2013.

Aina Y, Susman JL. Understanding comorbidity with depression and anxiety disorders. J Am Osteopathic Assoc. 2006;106(5 Suppl 2):S9–14.

Montgomery SA, Kasper S. Severe depression and antidepressants: focus on a pooled analysis of placebo-controlled studies on agomelatine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(5):283–91.

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–17.

Swiss Federal Social Insurance Office (FSIO). IV-Statistik 2008. Bern: BSV; 2007. http://www.bsv.admin.ch/dokumentation/zahlen/00095/00442/01378/index.html?lang=de. Accessed 17 Jan 2013.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO), Krankenhausstatistik und Statistik der sozialmedizinischen Institutionen 2005. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2007.http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/news/publikationen.html?publicationID=2601. Accessed 18 Jan 2013.

Sturny I, Schuler D, Camenzind P. Psychiatrische und psychotherapeutische Versorgung in der Schweiz—Monitoring 2008. Neuchatel: Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium, Obsan; 2009.

Swiss Drug Compendium 2009. Basel: Documed AG, Mohn Media—Mohndruck GmbH; 2009. http://www.kompendium.ch/home/prof/de. Accessed 1 Dec 2009.

Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, et al. Population-based study of first onset and chronicity in major depressive disorder. Arch General Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):513–20.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105.

Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Kelley D, et al. Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depression Anxiety. 2009;27(1):78–89.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). Arbeitslosigkeit in der Schweiz 2009, Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft SECO. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2010. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/03/22/publ.html?publicationID=4006. Accessed 18 Jan 2013.

Swiss Federal Social Insurance Office (FSIO). IV-Statistik Dezember 2009. Bern: BVS; 2009. http://www.bsv.admin.ch/dokumentation/zahlen/00095/00442/index.html?lang=de. Accessed 12 Jan 2009.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO), Arbeitsvolumenstatistik (AVOL). Wöchentliche Normalarbeitszeit der Vollzeitarbeitnehmenden nach Geschlecht, Nationalität und Wirtschaftsabschnitten 1991–2011. / Jährliche Dauer der Absenzen und Absenzenquote der Vollzeitarbeitnehmenden nach Geschlecht, Nationalität und Wirtschaftsabschnitten 1991–2011. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2013. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/03/02/blank/data/06.html. Accessed 21 Jan 2013.

Johnston K, Westerfield W, Momin S, et al. The direct and indirect costs of employee depression, anxiety, and emotional disorders—an employer case study. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(5):564–77.

Angst J, Gamma A, Rossler W, et al. Long-term depression versus episodic major depression: results from the prospective Zurich study of a community sample. J Affect Disorders. 2009;115(1–2):112–21.

Cuijpers P, Smit F, Oostenbrink J, et al. Economic costs of minor depression: a population-based study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115(3):229–36.

Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression Anxiety. 1998;7(1):3–14.

Screening and treatment for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1223–8.

Rohde P, Beevers CG, Stice E, et al. Major and minor depression in female adolescents: onset, course, symptom presentation, and demographic associations. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(12):1339–49.

Williams SB, O’Connor EA, Eder M, et al. Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e716–35.

Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(5):372–87.

Gostynski M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Gutzwiller F, et al. Depression among the elderly in Switzerland. Der Nervenarzt. 2002;73(9):851–60.

Weyerer S, Eifflaender-Gorfer S, Kohler L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in non-demented primary care attenders aged 75 years and older. J Affect Disorders. 2008;111(2–3):153–63.

Luppa M, Heinrich S, Matschinger H, et al. Direct costs associated with depression in old age in Germany. J Affect Disorders. 2008;105(1–3):195–204.

Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, et al. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch General Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):897–903.

Kessler R, White LA, Birnbaum H, et al. Comparative and interactive effects of depression relative to other health problems on work performance in the workforce of a large employer. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(7):809–16.

Mendlewicz J. Sleep disturbances: core symptoms of major depressive disorder rather than associated or comorbid disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(4):269–75.

Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF. Using chronic pain to predict depressive morbidity in the general population. Arch General Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):39–47.

Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, et al. The association of psychiatric comorbidity and use of the emergency department among persons with substance use disorders: an observational cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2008;8:17.

Kunik ME, Snow AL, Molinari VA, et al. Health care utilization in dementia patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):86–91.

Rutledge T, Vaccarino V, Johnson BD, et al. Depression and cardiovascular health care costs among women with suspected myocardial ischemia: prospective results from the WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(2):176–83.

Sayers SL, Hanrahan N, Kutney A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and greater hospitalization risk, longer length of stay, and higher hospitalization costs in older adults with heart failure. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2007;55(10):1585–91.

Le TK, Able SL, Lage MJ. Resource use among patients with diabetes, diabetic neuropathy, or diabetes with depression. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2006;4:18.

Egede LE, Ellis C. Diabetes and depression: global perspectives. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(3):302–12.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). Von Generation zu Generation - Entwicklung der Todesursachen 1970 bis 2004. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2008. http://www.bfs.admin.ch.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). Kosten des Gesundheitswesens nach Leistungserbringern 1995–2010. Neuchâtel: BFS; 2013. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/14/05/blank/key/leistungserbringer.html. Accessed 21 Jan 2013.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the recruiting psychiatrists and all patients for their cooperation. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Servier (Suisse) AG, Switzerland. The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

YT and TS designed the study and wrote the manuscript. YT performed the data analysis and is the guarantor for the overall content. All authors participated in data interpretation and approved the final version of the article before submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tomonaga, Y., Haettenschwiler, J., Hatzinger, M. et al. The Economic Burden of Depression in Switzerland. PharmacoEconomics 31, 237–250 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0026-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0026-9