Abstract

Parents and caregivers of children with ASD have reported significant stress and challenges in caregiving. However, stress coping research in parents and caregivers of children remains limited. This review attempted to close this gap. For this review, 37 studies investigating the (1) underlying themes, (2) contributing factors, and (3) psychological outcomes of ASD-related parental and caregiver coping, were selected from the literature. Results revealed that the two most useful coping resources, i.e., problem-focused coping (45.9 %) and social support (37.8 %), were supported by parental stress coping studies. Parents’ and caregivers’ use of coping strategies was also influenced by (1) demographical characteristics (i.e., gender, age, education, income, language) and psychological attributes (i.e., personality, cultural values, optimism, sense of coherence, benefit-finding and sense-making abilities, emotional health, coping styles), (2) child characteristics (i.e., age, gender, medical conditions, cognitive and adaptive functioning abilities, language difficulties, and behavior problems) and (2) situational variables (i.e., treatment availability, family function, and clinician referrals to support resources). Finally, methodological limitations in past studies were discussed. This review emphasized the importance of further examination on the coping mechanisms of parents/caregivers of children with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) present with difficulties in language communication and social interaction, and stereotyped and restricted patterns of behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Parents and caregivers of children with ASD experience significant stress and challenges in caregiving (Hayes and Watson 2012). ASD-related behavior problems or comorbidities such as adaptive functioning level, anxiety, hyperactivity, and obsessive-compulsive rituals are sources of stress for parents and caregivers, with special regard to low functioning children who demand the most support in daily living (Peters-Scheffer et al. 2012; Simonoff et al. 2008). Chronic exposure to stress related with caregiving for a child with disability have been observed to affect parents and caregivers in several domains of their lives such as poor health and mental health statuses (Johnson et al. 2011; Peters-Scheffer et al. 2012), disruptions to family functioning (Rao and Beidel 2009), and social isolation (Dunn et al. 2001).

Stress Coping in Parents and Caregivers of Children with ASD

Folkman and Lazarus (1985) proposed that general stress coping is a transitional process whereby coping methods vary across time and contexts to match the changing demands of stressful events. In addition, past studies on general stress coping have cited positive and negative general coping strategies to be associated with adaptive and maladaptive mental health outcomes, respectively (Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007; Taylor and Stanton 2007). Similar trends have also been observed among parents of children with ASD. For instance, factors such as child’s age and symptom severity (Gray 2006; Ingersoll and Hambrick 2011), parent personality (Ingersoll and Hambrick 2011), and family functioning (Altiere and von Kluge 2009) have been reported to affect parenting stress. In addition, among parents of children with ASD, adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies have been reported to relate positively and negatively with depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively (e.g., Benson 2010; Smith et al. 2008). Research on ASD-related stress coping methods, factors, and outcomes are well visited (e.g., Benson 2010; Gray 2006; Hayes and Watson 2012); however, the nature of parental/caregiver coping in ASD across different individuals and situations is less definite. This is an important area for further pursue as previous studies have noted the dynamic and stressor-dependent nature of coping, suggesting that general coping frameworks as previously derived may not be generically applicable to all parents and caregivers with children with ASD (Pakenham et al. 2005; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007). However, concluding reviews on the nature of stress coping in parents and caregivers of children with ASD remain limited currently.

Cultural Applications of ASD-Related Parental Coping

Considering the context-dependent nature of stress coping as conceptualized in Lazarus and Folkman (1985), caution is to be taken when applying general coping constructs across distinct cultural groups such as that between western and Asian parents of children with ASD (Chun et al. 2006; Sawang et al. 2006; Oyserman et al. 2002). Considering theoretical underpinnings of collectivism-individualism, Asian parents of children with ASD who may value group gains could be biased towards collectivistic problem-focused coping methods such as seeking treatments and gathering help from support networks, while western European parents more focused on self-gain may identify better with individualistic, self-focused coping such as passive appraisal and avoidance (Markus and Kitayama 1991; Oyserman et al. 2002; Sawang et al. 2006; Twoy et al. 2007). These findings suggest that pre-existing cultural worldviews could influence individual approaches towards stress coping (Sawang et al. 2006).

As studies have also linked problem-focused coping with positive mental health outcomes, there is possibility of a degree of mitigated risk for psychological maladjustment among Asian parents of children with ASD as compared to western European parents (Taylor and Stanton, 2007; Uchino 2006; Kawachi and Berkman 2001). Despite this, Asian parents have also been observed to internalize stressful feelings so they may avoid talking about personal problems to “save face” (e.g., Kim et al. 2001; Luong et al. 2009), or over-emphasize their child’s academic achievement to proliferate existing stressful feelings when children underperform (e.g., Lam and Mackenzie 2002; Mak and Ho 2007). Deeper insights into the potential impact of individual differences on ASD-related parental and caregiver stress coping mechanisms are critical to understanding coping outcomes at this point (Chun et al. 2006).

Importance of Parental and Caregiver Coping

Recent epidemiological studies cited a rising trend in ASD prevalence worldwide (Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention CDC 2012; Chien et al. 2011; Elsabbagh et al. 2012; Wong and Hui 2008). Despite increasing diagnostic prevalence, current research on parental/caregiver coping in Asian populations are limited to Asian parents living in the United States of America (USA) or East Asian populations such as China and Taiwan (e.g., Luong et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2011). Citing effects of individualism and collectivism on general stress coping as previously discussed, as well as rising diagnostic prevalence of ASD in Asian populations, cross-cultural differences in coping are important considerations for future development of coping strategies that are sensitive to the needs of different populations (Oyserman et al. 2002; Sawang et al. 2006).

The increasing prevalence of children with ASD raises questions on the statuses of mental health well-being, and availability and efficacy of support for families coping with a child with ASD (Hayes and Watson 2012; Lin et al. 2008; Moh and Magiati 2012). It is critical that healthcare providers first understand how different groups of parents and caregivers cope with caregiving stress before coping resources could be appropriately allocated (Pakenham et al. 2005). With better understanding of the individual and cultural nuances, healthcare providers may then better support parents and caregivers with ASD-relevant stress coping resources (Chun et al. 2006).

Review Objectives and Aims

Broadly, this review seeks to provide a summary of coping approaches adopted by parents and caregivers of children with ASD, as well as an overview of coping factors and coping outcomes, to assist healthcare providers in operationalizing resources and support for families of children with ASD. This review aims to (1) summarize the coping strategies adopted by parents and caregivers in providing care for their children with ASD, (2) examine factors (including the role of culture and individual differences) that influence parental/caregiver coping in ASD, and (3) report on the psychosocial outcomes of parent/caregiver coping in ASD.

Method

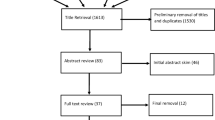

Searches using electronic literature databases were conducted to retrieve peer-reviewed articles published from 1970 to 2013 on the topic of ASD-related parental/caregiver coping. Articles on ASD-related parental/caregiver coping before 1970 were minimal, and they did not satisfy the current review’s inclusion criteria. The databases searched were PubMed, ERIC, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Science Direct, and Web of Science. These databases were chosen because academic papers on (1) psychological constructs and theories, and (2) families of children with ASD, are commonly published in these databases. Key terms were identified to narrow searches and to locate articles relevant to the review topic. The key terms used were as follows: parent, caregiver, parenting, caregiving, stress, coping, autism spectrum disorders, Asperger, and developmental disability.

Articles were selected using a two-stage screening process. Firstly, articles identified through the database searches were screened for relevance to the review topic (i.e., parental/caregiver coping in ASD) by reviewing abstracts. Articles were obtained in full text if the study of coping in parents/caregivers of children with ASD was mentioned in its abstract. Preliminary searches using key terms as defined revealed over 10,000 articles in each of the literature database searched. Fifty-one published abstracts mentioned the study of coping in parents/caregivers of children with ASD and, thus, were assessed to be relevant to the review topic by review authors. At the second stage, all 51 published articles were obtained in digital copies and were assessed on its relevance to the review objectives. Finally, 37 articles were selected for review because they met the following criteria: (1) study samples included parents/caregivers of children with a diagnosis of any category of ASD (50 % of study sample or more), and (2) studies have examined either (i) the underlying structure, distributions, and themes related to coping by parents of children with ASD using open-ended interviews or theory-based coping questionnaires/instruments; or (ii) individual factors affecting parental/caregiver coping; or (iii) psychosocial outcomes of parents/caregivers in relation with coping with caregiving stress. Fourteen studies did not fulfill the inclusion criteria as they have either explored coping-related psychological states (e.g., adaptation) instead of strategies employed by parents/caregivers, or included samples with a majority of non-ASD developmental disabilities, or specifically examined parent/caregiver support groups (i.e., a topic broad enough to warrant a literature review on its own; Boyd 2002), or explored effects of personal resources not amounting to effortful employment of stress-relieving mechanisms. Thus, these articles were not selected for this review.

Results

The current review examined a total of 37 studies exploring various aspects of parental/caregiver coping in ASD as summarized in Table 1. Results from the review are presented in the following sections: “Study Characteristics,” “Coping Structures and Themes,” “Coping Factors,” and “Coping Outcomes.”

Study Characteristics

Study Methodologies

The current review highlighted similar proportions of studies which have examined (1) ASD-related parental/caregiver coping structure or themes (48.6 %Footnote 1), (2) factors affecting parents’/caregivers’ use of coping strategies (45.9 %), and (3) psychosocial outcomes of parental/caregiver coping (43.2 %; respective studies indicated by alphabet superscripts in Table 1). It is also observed that 78.4 % of reviewed studies employed the use of quantitative methods (see rows 1–3, 6, 8–11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 19–24, 26–28, 30–34, and 35–37; column 2 in Table 1) more frequently than qualitative (24.3 %) designs (see rows 4, 5, 7, 12, 15, 18, 25, 29, and 35; column 2 in Table 1).

For studies investigating coping structures and themes, 38.9 % employed qualitative interviews (see rows 5, 12, 15, 18, 25, 29, and 35; column 2 in Table 1), 11.1 % used factor analysis statistical techniques (see rows 10 and 26; column 2 in Table 1), and 50.0 % employed experimental designs comparing between parents of children with ASD or non-ASD developmental disabilities or who were typically developing (see rows 2, 6, 13, 17, 24, 30, 32, 34, and 36; column 2 in Table 1). For studies examining coping factors, 5.9 % constituted a literature review (see row 4, column 2 in Table 1), 47.1 % used comparison analyses (see rows 7, 10, 15, 17, 19, 20, 24, and 27; column 2 in Table 1), and 47.1 % employed correlation/predictive analyses (see rows 9, 16, 21, 30, 32, 33, 36, and 37; column 2 in Table 1). Finally, all studies exploring psychosocial outcomes of coping used predictive analyses (see all studies superscripted with “c” in column 1 of Table 1).

Population Demographics

Studies in the current review sampled parents of children diagnosed with Autism, Asperger’s Syndrome, PDD-NOS, or ASD (refer to column 3 in Table 1). In all, study sample numbers were between the range of 20 to 1,005 parents for quantitative studies and between the range of 5 to 53 parents for qualitative studies. A large majority of study respondents were parents and only 3 (quantitative) studies included caregivers and grandparents of children with ASD in study sampling (see rows 28, 32, and 34; column 3 in Table 1). All qualitative studies reported a majority of mothers in study samples, and 91.9 % of quantitative studies reviewed reported a majority of mothers in study samples (refer to column 3 in Table 1). Fathers were included in 81.1 % of all studies reviewed but formed the minority group for each study as compared to study respondents who were mothers (refer to column 3 in Table 1).

A total of 56.8 % of studies reviewed reported parents’ age. Among these studies, parents’ mean ages ranged between 25 and 45.75 years. Educational level was reported in 54.1 % of these studies. Studies that have reported parents’ educational level cited a majority of their parent populations (>30 %) to have attained at least high school certification. In terms of child characteristics, 10.8 % of all studies reviewed reported on child symptom severity level or functioning level (see rows 6, 11, and 24; column 3 in Table 1). Of all studies reviewed, 10.8 % included parents of Asian heritage, and, among these, there were an equal proportion of quantitative (50.0 %; see rows 17 and 34, column 3 in Table 1) and qualitative (50.0 %; see rows 18 and 25, column 3 in Table 1) studies.

Coping Structures and Themes

Qualitative Studies

Review of cross-sectional qualitative studies on ASD-related parental coping derived several coping themes which included (1) seeking treatment or intervention, and information (Glazzard and Overall 2012; Hutton and Caron 2005; Lin et al. 2008; Marshall and Long 2010); seeking social support (Hutton and Caron 2005; Lin et al. 2008; Marshall and Long 2010); reappraisal and reframing (Lin et al. 2008; Marshall and Long 2010); adjusting and accommodating to child’s needs (Glazzard and Overall 2012; Hutton and Caron 2005); spirituality (Marshall and Long 2010); and seeking respite (Glazzard and Overall 2012). These findings highlighted the use of both problem-focused (e.g., treatments/interventions for child, reappraisal, and reframing) and emotion-focused (e.g., social support, spirituality, and respite) coping strategies in parents of children with ASD.

On the other hand, the review of longitudinal qualitative studies on ASD-related parental coping observed a general shift from problem-focused coping (i.e., seeking treatment, empowerment, and social support) to emotion-focused coping (i.e., religious coping and acceptance of child) over time (Gray 2002, 2006; Luong et al. 2009). Specifically, parents of children with ASD reported receiving less support from family members (Gray 2002, 2006), less engagement with healthcare service providers (Gray 2002, 2006), higher reliance on religion and family support (Gray 2006), and confidence in child’s strengths and abilities (Gray 2002, 2006) over time. These findings supported the changing nature of stress coping in parents of children with ASD.

Quantitative Studies Using Brief COPE, COPE, F-COPES, CHIP, and WOC Questionnaires

To determine the factor structure of coping using factor analytic techniques, studies based on the Brief COPE questionnaire revealed four domains of stress coping approaches relevant to parents and caregivers of children with ASD (Benson 2010; Hastings et al. 2005). These include (1) active avoidance/disengagement, (2) problem-focused/engagement, (3) positive coping/cognitive reframing, and (4) religious and denial coping/distraction (Benson 2010; Hastings et al. 2005). Frequencies of use of each coping approach were not documented in either Benson (2010) or Hastings et al. (2005). Recently, using the full-scaled version of the COPE inventory, Wang et al. (2011) observed three most frequently cited coping strategies among Chinese parents of children with Autism (in decreasing favor), i.e., (1) acceptance, (2) active coping, and (3) positive reinterpretation. When compared to parents of children with intellectual disabilities, Chinese parents also more frequently reported using active coping as a stress coping method (Wang et al. 2011).

Based on the family crisis oriented personal evaluation scale (F-COPES) questionnaire, reviewed studies highlighted two coping approaches most frequently cited among parents of children with ASD: (1) cognitive reframing (Hall 2012, mean score = 32.76; Luther et al. 2005, mean score = 31.30; Twoy et al. 2007, mean score = 30.15), and (2) acquiring social support (Hall 2012, mean score = 32.11; Luther et al. 2005, mean score = 27.50; Twoy et al. 2007, mean score = 24.90). Other coping approaches as measured by the F-COPES in varying degrees of usage include (1) mobilizing others to acquire and accept help (Hall 2012; Luther et al. 2005; Twoy et al. 2007), (2) passive appraisal (Hall 2012; Luther et al. 2005; Twoy et al. 2007), and (3) seeking spiritual support (Hall 2012; Lee 2009; Luther et al. 2005; Twoy et al. 2007). It is noted that Twoy et al. (2007) demonstrated a somewhat similar distribution of coping strategies as that of Luther et al. (2005), suggesting similar stress coping approaches among parents of children with ASD. On the other hand, parents of children with ASD differed most from the normal population on their rankings of passive appraisal (Luther et al. 2005; Twoy et al. 2007) and acquiring social support (Lee 2009), which suggested that passive appraisal and acquiring social support may be unique to ASD-related parental coping. Above findings based on the F-COPES supported similar coping trends such as using cognitive reframing and social support among parents of children with ASD, but implied coping differences between parents of children with ASD and those of typically developing children.

Based on studies using the coping health inventory for parents (CHIP; McCubbin et al. 1996), social support (encompassing spousal support) was cited to be most helpful for parents of children with ASD in times of stress (Hall and Graff 2011; Lee 2009). Other coping strategies that were moderately helpful included (1) family integration (Hall and Graff 2011), (2) cooperation (Hall and Graff 2011), (3) being optimistic about stressful situations (Hall and Graff 2011), (4) maintaining self-esteem and psychological stability (Lee 2009), and (5) understanding child’s condition through a professional (Lee 2009). Studies based on the CHIP showed that families benefited most from mutual support in stressful times (Hall and Graff 2011; Lee 2009).

Finally, based on studies that have used the ways of coping (WOC) questionnaire, wishful thinking/escape was most commonly cited by parents of children with ASD to manage stress (Rodrigue, Morgan and Geffken 1992; Sivberg 2002). Particularly, when compared with fathers of children with Down syndrome, those with children with autism engaged more frequently in wishful thinking (Rodrigue et al. 1992). When compared with parents of typically developing children, parents of children with ASD reported more frequent use of distancing and escaping, but less use of social support (Sivberg 2002). The lower use of social support is somewhat unusual as compared to other studies reviewed in this section and past studies, whereby social support was reported to be one of the most frequently employed coping strategy (e.g., Boyd 2002; Glazzard and Overall 2012; Hall 2012; Lin et al. 2008; Luther et al. 2005; Twoy et al. 2007).

Caveats to the Coping Construct

Two considerations arose from the review of studies focusing on ASD-related parental coping constructs and themes. Firstly, the coping construct is malleable and flexible to the contexts by which it is applied (Folkman and Lazarus 1985; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007). For instance, although factor analytic findings on the Brief COPE fitted well with a four-factor structure, content differences in Brief COPE domains between Benson (2010) and Hastings et al. (2005). Particularly, “coping by humor” was grouped within the “positive coping” domain in Benson (2010) but categorized under the “distraction” domain in Hastings et al. (2005), and “religious” coping strategies merged with “cognitive reframing” in Benson (2010) but stood as one domain in Hastings et al. (2005).

Secondly, while reviewed studies in this section revealed several themes/commonalities in stress coping among parents and caregivers of children with ASD, effects of influencing factors and outcomes of ASD-related parental stress coping have been suggested (Gray 2006; Hall 2012; Hall and Graff 2011; Hastings et al. 2005; Pakenham et al. 2005; Twoy et al. 2007). The sections “Coping Factors” and “Coping Outcomes” attempt to close this gap.

Coping Factors

A total of 17 reviewed studies highlighted a range of factors contributing towards parents’ and caregivers’ use of stress coping strategies. Findings are summarized in “Parent factors,” “Child factors,” and “Contextual factors.”

Parent Factors

Previous research has observed moderating/mediating effects of demographic characteristics such as parent’s gender (Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Gray 2003; Hastings et al. 2005; Lee 2009; Pottie and Ingram 2008), age (Gray 2006; Luong et al. 2009), spoken language (Twoy et al. 2007), and income and educational level (Mandell and Salzer 2007) on their use of coping strategies and resources. In addition, parents’ and caregivers’ psychological attributes and statuses such as personality (Ingersoll and Hambrick 2011), cultural values (Twoy et al. 2007), optimism (Lee 2009), sense of coherence (Pisula and Kossakowska 2010), benefit-finding/sense-making abilities (Pakenham et al. 2004), emotional health (Cappe et al. 2011), and existing coping styles (Hall and Graff 2011) have been reported to impact on parental/caregiver coping in ASD.

Comparing across all parent factors, parent’s gender and age have received most attention in research (e.g., Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Gray 2003; Hastings et al. 2005; Lee 2009; Luong et al. 2009; Pottie and Ingram 2008). For gender, mothers of children with ASD have reported employing more social support, problem-focused coping, and spiritual coping strategies than fathers of the same children; whereas fathers reported more emotional coping (e.g., suppressing frustrations and avoiding family problems by going to work) than mothers in the same family (Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Gray 2003; Hastings et al. 2005; Lee 2009). On the other hand, in consideration of parents’ age, younger parents of children with ASD have been reported to employ more problem-focused coping than older parents, while older parents of children with ASD engaged in more emotion-focused coping than young parents (Gray 2006).

It was highlighted earlier in this review that cultural background and values potentially affect parents’ and caregivers’ use of coping strategies (Lin et al. 2008; Luong et al. 2009; Twoy et al. 2007; Sawang et al. 2006). Cultural differences in parental/caregiver coping were also observed in current study findings. For instance, as reviewed in this study, studies based on a majority of Asian participants reported frequent use of active coping strategies such as seeking treatments and social support, and cognitive reframing (e.g., Lin et al. 2008; Luong et al. 2009; Twoy et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2011). On the other hand, Caucasian participants were noted to report more frequent use of passive coping strategies such as distancing, escaping, and wishful thinking (e.g., Pisula and Kossakowska 2010; Rodrigue et al. 1992; Sivberg 2002; Twoy et al. 2007).

Child Factors

It is observed from this review that factors such as child’s age (e.g., Hastings et al. 2005; Mandell and Salzer 2007; Smith et al. 2008), gender (e.g., Mandell and Salzer 2007), ASD diagnosis (e.g., Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Lee 2009), cognitive abilities (Boyd 2002), adaptive functioning (Hall and Graff 2011), language difficulties (Mandell and Salzer 2007), severity of child’s condition (e.g., Resch et al. 2012), and behavior problems (e.g., Gray 2006; Hall 2012; Mandell and Salzer 2007) impact on ASD-related parental/caregiver coping.

Comparing all child factors, the effects of child’s age on parental and caregiver coping are most frequently reported (Hastings et al. 2005; Mandell and Salzer 2007; Smith et al. 2008). Past research examining the effects of child’s age provided further support to previous evidence on parents’ transitional process of problem-focused to emotion-focused coping over time (Gray 2006; Hastings et al. 2005; Luong et al. 2009; Mandell and Salzer 2007; Smith et al. 2008). Particularly, it is suggested that child’s presenting behavioral challenges persisted over time and, hence, parents came to better appreciate the individual qualities of their child over time instead of resisting them (Gray 2002, 2006; Luong et al. 2009; Pakenham et al. 2004).

Contextual Factors

Apart from individual characteristics, parents’ and caregivers’ approach towards stress coping is also context-dependent in times of stress. Situational factors observed to impact on parental/caregiver coping include the availability of treatment services (e.g., Gray 2006), clinician referrals to support resources (e.g., Mandell and Salzer 2007), family functioning (e.g., Altiere and von Kluge 2009), and the combined effects of community support availability and child behavior problems (e.g., Hall 2012). These factors impact on parents’ engagement of instrumental services, social support and family coping strategies.

Coping Outcomes

To provide a well-rounded illustration of ASD-related parental and caregiver coping mechanisms, psychosocial outcomes of stress coping in parents and caregivers of children with ASD were reviewed in 16 studies. Findings are summarized in “Parent Outcomes,” and “Sibling outcomes.”

Parent Outcomes

Among parents of children with ASD, previous research observed a general trend towards higher levels of stress, depression, anxiety, anger, and negative affect when emotion-focused coping (e.g., disengagement, denial, and wishful thinking) was frequently employed (Abbeduto et al. 2004; Benson 2010; Cappe et al. 2011; Carter et al. 2009; Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Ekas et al. 2009; Hastings et al. 2005; Ingersoll and Hambrick 2011; Pakenham et al. 2005; Pottie and Ingram 2008; Smith et al. 2008); and lower depression, anxiety, anger and negative mood symptoms, and higher positive moods when problem-focused/active coping (e.g., seeking social support, cognitive reframing, and planning) is employed (Carter et al. 2009; Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Dunn et al. 2001; Ekas et al. 2009; Gray & Holden 1992; Hastings et al. 2005; Pottie and Ingram 2008; Resch et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2008). Other related outcomes of emotion-focused coping include poor family integration, limitations on family opportunities, and parent pessimism and nervousness (Cappe et al. 2011; Lyons et al. 2010). In this review, there were more studies that reported significant relationships between mental health outcomes with emotion-focused coping (87.5 %) than with problem-focused coping (56.3 %).

Sibling outcomes

Of special note is the psychological well-being of siblings of children with ASD, as Lin et al. (2008) observed that some parents shared caregiving responsibilities with siblings of the child with ASD diagnosis, risking poor psychological adjustment in siblings of children with ASD when they are not supported with appropriate long-term coping support and resources (e.g., Gold 1993; Hastings 2003; Kaminsky and Dewey 2002). Some studies have observed typically developing siblings, who were given additional caregiving roles but without family support, to report more depressive symptoms and poor psychological adjustment (Gold 1993; Hastings 2003; Kaminsky and Dewey 2002). The psychological well-being of siblings of children with ASD is currently underrepresented in research.

Discussion

A review of 37 research studies underscored 2 main coping strategies that parents of children with ASD adopt in coping with caregiving stress. These were problem-focused coping (including seeking instrumental support, planning, problem-solving, confrontation, compromising, changing expectations, and sense-making) and seeking social support (from immediate and extended family, friends, co-workers, and healthcare professionals). The current review also revealed other stress coping strategies employed by parents of children with ASD (discussed further in “Multidimensional Framework of Coping”).

Multidimensional Framework of Coping

Similarities in the underlying concepts of coping strategies as reviewed suggest the possibility of a multidomain framework of parental coping that is built upon clusters of similar coping strategies in ASD. Based on this proposition, coping strategies which align in content and definition were clustered together and four domains of coping were derived by review authors as follows: (1) active avoidance (e.g., behavioral disengagement, distraction, social withdrawal, distancing, escaping, denial, ignoring child, and passive appraisal), (2) spiritual coping (e.g., seeking respite, optimism, and religion-focused coping), (3) cognitive reframing (e.g., acceptance, changing expectations, shifting priorities and goals in life, appreciation of child’s qualities, and humor), and (4) problem solving (e.g., seeking resource empowerment, setting up treatment plans, active engagement with child, mobilizing support from others, maintaining cooperation within family, and family integration).

The use of a multidimensional framework to explain parental coping in ASD has been attempted in previous studies (e.g., Luong et al. 2009; Hastings et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2011). However, findings from both qualitative and quantitative studies on the structural framework of the coping construct have not been consistent (e.g., Benson 2010; Hastings et al. 2005; Luong et al. 2009). It is suggested that the construct of parental coping in ASD does not sit well with a fixed structure. In agreement with this, the current review highlighted structural differences in the factor grouping of the Brief COPE subscales in two studies measuring parental coping in ASD (Benson 2010; Hastings et al. 2005). In addition, previous studies using the Brief COPE on non-ASD parent populations have also found conflicting results on the number of factors that make up the structure of coping (Greening and Stoppelbein 2007; Hasking and Oei 2002; Pang et al. 2013). As coping is a modifiable construct that is dependent upon the demands of the stressful event and individual differences, determination of the factor structure of coping before conducting further statistical analyses is recommended for future research in this area (Folkman and Lazarus 1985; Hasking and Oei 2002; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007).

Influential Factors

From this review, a range of factors were observed to influence parental and caregiver coping, which include parent (gender and age most frequently reported, e.g., Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Gray 2006) and child (age most frequently reported, e.g., Smith et al. 2008) characteristics, and situational conditions (e.g., Gray 2006; Altiere and von Kluge 2009).

In terms of parent gender, secondary factors such as parents’ degree of adherence to traditional gender roles could impact on ASD-related parental/caregiver coping (Gray 2003). For instance, Gray (2003) previously suggested that fathers endorsing traditional role of a family provider could intentionally avoid caregiver responsibilities by over emphasizing their role as a breadwinner and focusing their time on work extensively. In addition, Gau et al. (2012) also observed mothers of children with ASD to bear more personal responsibility on caregiving responsibilities than fathers. Healthcare professionals providing support to families of children with ASD may benefit from understanding the dynamics of gender differentiation in parents’ distribution of caregiving responsibilities (Gray 2003).

On the other hand, the impact of parents’ and children’s age on ASD-related parental coping has reinforced evidence on the changing nature of coping (Gray 2002, 2006; Luong et al. 2009). For instance, it is postulated that parents shift from problem-focused to emotion-focused coping over time due to a lack of improvement in child’s core symptoms and changes in caregiving support availability (which potentially facilitated parents’ growing appreciation of their child over time) (Gray 2006; King et al. 2006). The changing nature of behavioral problems presented in the child with ASD render parents’ and caregivers’ flexibility and adaptability important towards adaptive stress coping (Gray 2006; Hastings et al. 2005; Luong et al. 2009; Marshall and Long 2010).

Findings on coping factors also raised the important consideration of novel coping strategies not previously examined (Kuo 2011). For instance, it is likely that the interactions between a wide range of coping factors and stressor demands gave rise to an extensive, and sometimes novel, spectrum of coping strategies used by parents of children with ASD (Kuo 2011). Previously, Hall and Graff (2011) reported that parents of children with ASD maintained strong family integration and cooperation to cope with stress, even though this construct did not necessarily gel with traditional paradigms of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Therefore, in addition to validating commonly reported coping strategies, it is also important to continue exploring novel coping strategies derived in parents’ experience of providing care.

Cultural Effects

It is interesting to note that while Asian parents/caregivers of children with ASD more frequently reported the use of positive reinterpretation than Caucasian parents/caregivers, Caucasian parents/caregivers reported higher use of passive appraisal such as distancing and escaping than Asian parents/caregivers (Lin et al. 2008; Luong et al. 2009; Twoy et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2011). Potentially, based on the individualism-collectivism paradigm, highly collectivistic Asian parents value harmony and interdependency and, thus, are more willing to adjust themselves to accommodate the family in times of stress (Lam and Zane 2004). Conversely, highly individualistic Caucasian parents may be relatively more self-motivated to adjust their surroundings either by confronting the stressful event or avoiding it altogether (Lam & Zane, 2004). On a related note, Gau et al. (2012) suggested that in traditional, patriarchal Chinese families, mothers tended to take on full caregiving responsibilities and become highly stressed when caregiving duties expand and involvement deepens. As theories of self-construals posited that coping behaviors are more likely to be aligned with one’s cultural values, cultural impact on parental coping behaviors and associated psychological outcomes should be regarded with emphasis when research in this topic is attempted (Markus and Kitayama 1991). The current review revealed minimal studies investigating cross-cultural effects on parental coping in ASD. In view of possible impact of cultural nuances on parental coping, it is recommended that future studies consider the effects of cultural values on ASD-related parental/caregiving coping.

Psychological Outcomes

Although past studies have supported links between parents’ use of coping strategies and psychological well-being, it is to be noted that most parental/caregiver coping studies in ASD have based their findings on models of general coping which were derived from typical community populations (e.g., Benson 2010; Cappe et al. 2011; Carter et al. 2009; Hastings et al. 2005; Ingersoll and Hambrick 2011; Lee 2009). In this review, it was interesting to note that positive relationships between problem-focused coping and adaptive mental health outcomes were reported only in Hastings et al. (2005), but not in Benson (2010), although well-established links between positive coping strategies and adaptive mental health outcomes were reported in community health research previously (e.g., Penley, Tomaka, & Wiebe, 2002). Providing support, Pakenham et al. (2005) and Sivberg (2002) highlighted that problem-focused coping strategies derived from general coping questionnaires may not be relevant to managing stressors encountered by parents of children with ASD. As there are currently no available tools known to reviewers for measuring ASD-specific coping strategies, it is recommended that future research in this area consider establishing the structure of coping in this parent population before determining the psychological outcomes of coping methods (Hastings et al. 2005; Benson 2010).

Methodological Caveats

This review identified some methodological considerations from previous research on ASD-related parental/caregiver coping. Firstly, past studies employed mostly cross-sectional designs. The use of longitudinal research designs may be more useful in drawing deeper insights on the relationships between coping and its qualifying factors (Taylor and Stanton 2007). An alternative is to employ daily diary designs, which can help to monitor daily changes in coping strategies used by parents/caregivers of children with ASD, and as well as the elucidation of factors potentially contributing towards parenting/caregiving stress (Ekas and Whitman, 2011; Pottie and Ingram 2008; Smith et al. 2008).

Secondly, data collection tools are critical to the conceptualization of the coping construct. For instance, in open-ended interviews, unexplored coping strategies that parents have developed over experience could be tapped via parents’ open sharing about their experiences (Glazzard and Overall 2012). On the other hand, parent responses on a theory-based coping questionnaire are limited by the theoretical construct defining the questionnaire (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007). Practically, standardized coping questionnaires are suitable for parents with less time outside of caregiving commitments to their child with ASD (Lin et al. 2008). As middle-ground, mixed-method designs offer the merits of collecting data in detail using open-ended interviews, while saving time and efforts with survey questions (Creswell 2012).

Thirdly, while this review reported the use of coping strategies, there remains a lack of evidence regarding the effective use of the identified strategies and associated outcomes. For example, it was unclear from reviewed studies what the optimal frequency usage was in order to produce maximum outcome of minimal stress, anxiety, and depression and, at the same time, to maximize quality of life. Furthermore, interactional relationships between caregiving stress, coping, and mediating factors of parents’ coping behaviors were not commonly examined together in single studies. Considering issues on the factor structure of the coping construct as previously discussed, it is argued that a review evaluating findings on the basic structure of coping, such as one of the sections in this paper, is first needed, before further work is pursued in summarizing the pathway mechanisms of coping.

Finally, findings from this review are limited within the stress coping literature focusing on parents of children with ASD. The study of stress and coping among parents/caregivers of children with ASD is a multiaxial endeavor, which needs to be operationalized in the context of influences from individual differences and psychological outcomes associated with stress exposure and coping (e.g., Benson and Karlof 2009; Dunn et al. 2001; Lecavalier et al. 2006). The current review aimed to examine findings associated with ASD-related parental/caregiver coping only, and the establishment of statuses and relationships between ASD-related parental/caregiver stress, coping, and psychological outcomes demand a separate study. Furthermore, in most voluntary survey research, sampling bias is likely, such that parents and caregivers who were more active and open about sharing their experiences and views may be more willing to participate in voluntary research studies (e.g., Luong et al. 2009; Lin et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2011). Relating this with review findings, the most frequently reported coping strategy (i.e., problem-focused coping) employed by parents and caregivers is consistent with suggested bias in participants being more active and forthcoming. Thus, future studies in ASD-related parental/caregiver coping may consider revising recruitment strategies to account for parents and caregivers who are less forthcoming of their feelings and experiences.

Conclusion

This review highlighted a lack of strong empirical evidence on the structure of coping and on the efficiency of coping resources to achieve positive emotional and well-being outcomes. This review also cautions against an acceptance of the coping construct at face value and recommends that the structure of coping be first established, before determining links between coping and associated outcomes. In this note, mental health professionals need to be mindful of the coping mechanisms that are relevant to parents’ caregiving needs, so as to better equip parents with positive coping resources.

Notes

Percentages in this section do not add up to 100 because of studies with overlapping characteristics or percentage decimals.

References

Abbeduto, L., Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Krauss, M. W., Orsmond, G., & Murphy, M. M. (2004). Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, Down syndrome, or Fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 109(3), 237–254.

Altiere, M. J., & von Kluge, S. (2009). Family functioning and coping behaviors in parents of children with autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(1), 83–92.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Benson, P. R. (2010). Coping, distress, and well-being in mothers of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 217–228.

Benson, P. R., & Karlof, K. L. (2009). Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: a longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(2), 350–362.

Boyd, B. A. (2002). Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(4), 208–215.

Cappe, E., Wolff, M., Bobet, R., & Adrien, J. L. (2011). Quality of life: a key variable to consider in the evaluation of adjustment in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders and in the development of relevant support and assistance programmes. Quality of Life Research, 20, 1279–1294. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-9861-3.

Carter, A. S., Martínez-Pedraza, F. D. L., & Gray, S. A. O. (2009). Stability and individual change in depressive symptoms among mothers raising young children with ASD: maternal and child correlates. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 1270–1280. doi:10.1002/jclp.20634.

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—autism and developmental disabilities Monitoring network, 14 Sites, United States, 2008. Surveillance Summaries, 61(SS03), 1–19.

Chien, I. C., Lin, C. H., Chou, Y. J., & Chou, P. (2011). Prevalence and incidence of autism spectrum disorders among national health insurance enrollees in Taiwan from 1996 to 2005. Journal of Child Neurology, 26(7), 830–834. doi:10.1177/0883073810393964.

Chun, C. A., Moos, R. H., & Cronkite, R. C. (2006). Culture: a fundamental context for the stress and coping paradigm. In P. T. P. Wong & L. C. J. Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 29–53). New York: Springer.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Dabrowska, A., & Pisula, E. (2010). Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre‐school children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(3), 266–280.

Dunn, M. E., Burbine, T., Bowers, C. A., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2001). Moderators of stress in parents of children with autism. Community Mental Health Journal, 37(1), 39–52.

Ekas, N. V., Whitman, T. L., & Shivers, C. (2009). Religiosity, spirituality, and socioemotional functioning in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(5), 706–719.

Ekas, N. V., & Whitman, T. L. (2011). Adaptation to daily stress among mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder: The role of daily positive affect. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 41(9), 1202–1213.

Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y. J., Kim, Y. S., & Fombonne, E. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research, 5, 160–179. doi:10.1002/aur.239.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–170.

Gau, S. S. F., Chou, M. C., Chiang, H. L., Lee, J. C., Wong, C. C., Chou, W. J., et al. (2012). Parental adjustment, marital relationship, and family function in families of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 263–270.

Glazzard, J., & Overall, K. (2012). Living with autistic spectrum disorder: parental experiences of raising a child with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). Support for Learning, 27(1), 37–45.

Gold, N. (1993). Depression and social adjustment in siblings of boys with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 23(1), 147–163.

Gray, D. E. (2002). Ten years on: a longitudinal study of families of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27(3), 215–222.

Gray, D. E. (2003). Gender and coping: the parents of children with high functioning autism. Social Science & Medicine, 56(3), 631–642.

Gray, D. E. (2006). Coping over time: the parents of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50, 970–976. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00933.x.

Gray, D. E., & Holden, W. J. (1992). Psycho-social well-being among the parents of children with autism. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 18(2), 83–93.

Greening, L., & Stoppelbein, L. (2007). Brief report: pediatric cancer, parental coping style, and risk for depressive, posttraumatic stress, and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(10), 1272–1277.

Hall, H. R. (2012). Families of children with autism: behaviors of children, community support and coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 35(2), 111–132.

Hall, H. R., & Graff, J. C. (2011). The relationships among adaptive behaviors of children with autism, family support, parenting stress, and coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 34(1), 4–25. doi:10.3109/01460862.2011.555270.

Hasking, P. A., & Oei, T. P. (2002). Confirmatory factor analysis of the COPE questionnaire on community drinkers and an alcohol-dependent sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(5), 631–640.

Hastings, R. P. (2003). Behavioral adjustment of siblings of children with autism engaged in applied behavior analysis early intervention programs: the moderating role of social support. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(2), 141–150.

Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Brown, T., Ward, N. J., Espinosa, F. D., & Remington, B. (2005). Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of preschool and school-age children with autism. Autism, 9(4), 377–391. doi:10.1177/1362361305056078.

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2012). The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642.

Higgins, D. J., Bailey, S. R., & Pearce, J. C. (2005). Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 9(2), 125–137.

Hutton, A. M., & Caron, S. L. (2005). Experiences of families with children with autism in rural New England. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(3), 180–189.

Ingersoll, B., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2011). The relationship between the broader autism phenotype, child severity, and stress and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 337–344. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.04.017.

Johnson, N., Frenn, M., Feetham, S., & Simpson, P. (2011). Autism spectrum disorder: parenting stress, family functioning and health-related quality of life. Families, Systems & Health, 29(3), 232–262.

Kaminsky, L., & Dewey, D. (2002). Psychosocial adjustment in siblings of children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 225–232. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00015.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of urban health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 78(3), 458–467.

Kim, B. S. K., Atkinson, D. R., & Umemoto, D. (2001). Asian cultural values and the counseling process: current knowledge and directions for future research. The Counseling Psychologist, 29, 570–603.

King, G. A., Zwaigenbaum, L., King, S., Baxter, D., Rosenbaum, P., & Bates, A. (2006). A qualitative investigation of changes in the belief systems of families of children with autism or Down syndrome. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32(3), 353–369.

Kuo, B. C. (2011). Culture's consequences on coping: theories, evidences, and dimensionalities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1084–1100.

Lam, L. W., & Mackenzie, A. E. (2002). Coping with a child with Down syndrome: the experiences of mothers in Hong Kong. Qualitative Health Research, 12(2), 223–237.

Lam, A. G., & Zane, N. W. S. (2004). Ethnic differences in coping with interpersonal stressors: a test of self-construals as cultural mediators. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 446–459. doi:10.1177/0022022104266108.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal & Coping. New York: Springer.

Lecavalier, L., Leone, S., & Wiltz, J. (2006). The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(3), 172–183.

Lee, G. K. (2009). Parents of children with high functioning autism: how well do they cope and adjust? Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 21(2), 93–114.

Lin, C., Tsai, Y., & Chang, H. (2008). Coping mechanisms of parents of children recently diagnosed with autism in Taiwan: a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(20), 2733–2740. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02456.x.

Luong, J., Yoder, M. K., & Canham, D. (2009). Southeast Asian parents raising a child with autism: a qualitative investigation of coping styles. The Journal of School Nursing, 25(3), 222–229. doi:10.1177/1059840509334365.

Luther, E. H., Canham, D. L., & Cureton, V. Y. (2005). Coping and social support for parents of children with autism. The Journal of School Nursing, 21(1), 40–47. doi:10.1177/10598405050210010901.

Lyons, A. M., Leon, S. C., Phelps, C. E. R., & Dunleavy, A. M. (2010). The impact of child symptom severity on stress among parents of children with ASD: the moderating role of coping styles. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(4), 516–524.

Mak, W. W. S., & Ho, G. S. M. (2007). Caregiving perceptions of Chinese mothers of children with intellectual disability in Hong Kong. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 145–156. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00309.x.

Mandell, D. S., & Salzer, M. S. (2007). Who joins support groups among parents of children with autism? Autism, 11(2), 111–122.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

Marshall, V., & Long, B. C. (2010). Coping processes as revealed in the stories of mothers of children with autism. Qualitative Health Research, 20(1), 105–116.

McCubbin, H., Thompson, A., & McCubbin, M. (1996). Family assessment: resiliency, coping and adaptation—inventories for research and practice. Madison: University of Wisconsin System.

Moh, T. A., & Magiati, I. (2012). Factors associated with parental stress and satisfaction during the process of diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 293–303.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72.

Pakenham, K. I., Sofronoff, K., & Samios, C. (2004). Finding meaning in parenting a child with Asperger syndrome: correlates of sense making and benefit finding. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(3), 245–264.

Pakenham, K. I., Samios, C., & Sofronoff, K. (2005). Adjustment in mothers of children with Asperger syndrome: an application of the double ABCX model of family adjustment. Autism, 9(2), 191–212.

Pang, J., Strodl, E., & Oei, T. P. (2013). The factor structure of the COPE Questionnaire in a sample of clinically depressed and anxious adults. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, In Press

Penley, J. A., Tomaka, J., & Wiebe, J. S. (2002). The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25(6), 551–603.

Peters-Scheffer, N., Didden, R., & Korzilius, H. (2012). Maternal stress predicted by characteristics of children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 696–06. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.10.003.

Pisula, E., & Kossakowska, Z. (2010). Sense of coherence and coping with stress among mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(12), 1485–1494.

Pottie, C. G., & Ingram, K. M. (2008). Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with autism: a multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 855–864. doi:10.1037/a0013604.

Rao, P. A., & Beidel, D. C. (2009). The impact of children with high-functioning autism on parental stress, sibling adjustment, and family functioning. Behavior Modification, 33(4), 437–451.

Resch, J. A., Benz, M. R., & Elliott, T. R. (2012). Evaluating a dynamic process model of wellbeing for parents of children with disabilities: a multi-method analysis. Rehabilitation Psychology, 57(1), 61–72.

Rodrigue, J. R., Morgan, S. B., & Geffken, G. R. (1992). Psychosocial adaptation of fathers of children with autism, Down syndrome, and normal development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(2), 249–263.

Sawang, S., Oei, T. P. S., & Goh, Y. W. (2006). Are country and culture values interchangeable? A case example using occupational stress and coping. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 6, 2205–2219. doi:10.1177/1470595806066330.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929.

Sivberg, B. (2002). Family System and Coping Behaviors. Autism, 6(4), 397–409. doi:10.1177/1362361302006004006.

Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). The Development of Coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 119–144.

Smith, L. E., Seltzer, M. M., Tager-Flusberg, H., Greenberg, J. S., & Carter, A. S. (2008). A comparative analysis of well-being and coping among mothers of toddlers and mothers of adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 876–889.

Taylor, S., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 377–401.

Twoy, R., Connolly, P. M., & Novak, J. M. (2007). Coping strategies used by parents of children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 19, 251–260.

Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5.

Wang, P., Michaels, C., & Day, M. (2011). Stresses and coping strategies of Chinese families with children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(6), 783–795. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1099-3.

Wong, V. C. N., & Hui, S. L. H. (2008). Epidemiological study of autism spectrum disorder in China. Journal of Child Neurology, 23(1), 67–72.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Oei is now an emeritus professor at the University of Queensland. He is also a visiting professor at Beijing Normal University in Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, W.W., Oei, T.P.S. Coping in Parents and Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD): a Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 1, 207–224 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0021-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0021-x