Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed at examining the reliability and validity of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS) among a sample of Lebanese adolescents (15 to 18 years old).

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study that was conducted between May and June 2020 and had enrolled 555 Lebanese adolescents. To assess the internal structure of the TOS scale, we administered the confirmatory factor analysis based on polychoric correlation matrix using Weighted Least Squares with Means and Variance Adjusted estimation (WLSMV) method in Mplus v 7.2 as suggested in the original validation paper. To assess the degree to which the Lebanese adaptation converges with the original scale, we have conducted the Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MGCFA; estimated as CFA) between the data reported in the current paper and from the original validation paper.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 16.66 ± 1.01 years, with 76.1% females. The bi-dimensional model fitted the data well (χ2(118) = 429.09; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.954; RMSEA = 0.069[0.062, 0.076]). The latent factors were highly correlated (ρ = 0.74; p < 0.001), and the strength of the standardized factor loadings was adequate on both factors (i.e., all > 0.60). The fit indices of the scalar model were at the boundary of the threshold and thus, with some pinch of caution, it might be interpreted as invariant (i.e., having equal item intercepts across groups). We have identified latent mean differences in orthorexia nervosa (0.30; p < 0.001), where Spanish individuals scored higher, but we did not find any differences in the healthy eating (0.03; p = 0.636).

Higher DOS scores were significantly correlated with higher scores on the TOS subscale OrNe (r = 0.715; p < 0.001) as well as with higher scores on the TOS subscale HeOR (r = 0.754; p < 0.001). Higher ORTO-R scores were significantly associated with less TOS OrNe (r = − 0.437; p < 0.001) and TOS HeOr (r = − 0.305; p < 0.001) scores, respectively.

Conclusion

The Arabic version of the TOS can be considered a reliable valuable instrument to assess the ON tendencies and behaviors in Lebanese adolescents, emphasizing the fine contrast between ON’s two dimensions: healthy vs. pathological.

Level V

Opinions of authorities, based on descriptive studies, narrative reviews, clinical experience, or reports of expert committees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For some time now, concerns about pathological healthful eating is of interest among researchers and clinicians. Termed “Orthorexia Nervosa (ON)” by Bratman and Knight in 1997 [1], the emerging eating behavior was described as the pathological obsession for proper nutrition through a “restrictive diet, a focus on food preparation, and ritualized patterns of eating” [2]. Not considered as a disease by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), orthorexia nervosa can be conceptualized as a life-threatening behavior where in extreme situations, subjects with orthorexic tendencies would prefer starvation over eating anything they consider impure and poisonous to their health [3, 4].

A greater number of articles that have recently been published in the literature have referred to ON as a keyword through the past years [5, 6]. However, no universal definition of ON has been shared yet, since its diagnostic criteria were still debatable, as well as its screening and psychometric instruments [7]. Until recently, research in this field has been hindered by the dearth of validated ON measurement tools that may distinguish between healthy and pathological “healthful eating” [8, 9].

The Bratman’s Orthorexia Test (BOT) was the first created tool to specifically measure ON [5]. As far as we know, there were not any evidence about the internal structure and/or reliability of this informal self-assessment tool [3, 10, 11]. Based on the BOT and questions about psychological disorders and personality profiles that were drawn from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) [12], the ORTO-15 questionnaire was developed. Initially created by Donini et al., in the Italian language [11], it was validated in many other languages: Arabic [13], Turkish [14], Polish [15], German [16], and Spanish [17]. Despite being the most used questionnaire for measuring ON, the ORTO-15 is known for its important limitations regarding its psychometric characteristics. It was criticized for instability in its internal consistency’s values; some studies have reported low values of Cronbach’s alphas, while others have reported higher values (range: 0.62–0.82 [18, 19]). Content validity issues were also described since the tool was used to identify the healthy eating patterns, even those without pathological aspects, what may explain the high rate of ON tendencies and behaviors that was reported in multiple studies [9, 19,20,21]. Doubts regarding the scoring techniques and interpretations [19, 22] were also documented. Consequently, these metric discrepancies led to the development of a range of new tools to assess ON, such as the Eating Habits Questionnaire (EHQ) [23], the Düsseldorf Orthorexia Scale (DOS) [24], and even a revised version of the ORTO-15 itself, the ORTO-R [25].

A propitious new instrument is the Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS) [10]. A major advantage of the TOS tool is that it differentiates between two dimensions of orthorexia: healthy orthorexia (HeOr) and orthorexia nervosa (OrNe) [18]. At first, the initial TOS was developed by Barrada and Roncero in a 31-item version measuring both HeOr and OrNe. Both authors have reviewed ON’s literature, have participated in the validation of the Spanish ORTO-15 version, and have published many other eating disorders studies, leading to a final shortened and refined version of the TOS, a 17-item questionnaire. In the latter, two separate factors were identifiable healthy orthorexia (HeOr) and orthorexia nervosa (OrNe), which were, respectively, assessed with nine and eight items [10]. In its original Spanish version, the TOS showed a satisfactory internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha reaching 0.85 for HeOr and 0.81 for OrNe [10]. Also, the test–retest correlation with an 18-month time-lapse was higher than 0.70 for both HeOr and OrNe [10].

To note that the majority of the studies about ON were mostly conducted in adults’ populations, while few were the studies targeting ON among adolescent populations. Few were the published studies about ON in Arab countries, as well [26]; in Lebanon, most of them mainly targeted adults and university students [13, 27,28,29,30,31,32].

The period of adolescence poses a risk for developing distorted eating behaviors in general [33, 34], and ON in particular [7, 35,36,37]. A fine line exists between what may be considered a maladaptive versus a healthy eating behavior in such a population. In fact, Lebanese adolescents’ dietary styles would differ from other adolescents in Europe and the United States, regarding the food availability and cost [38]. While the Lebanese adolescents grew up on a Mediterranean food table where seasonal fruits and vegetables are widely available in the country, and extensively incorporated in most traditional ethnic dishes [39], not all of them showed an equal nutritional knowledge [38]. This heterogeneity in the source of nutritional knowledge in the Lebanese adolescents, weather from inequalities in the socio-economic classes, or the accessibility to media influences, or other factors [38], makes the Lebanese adolescents more prompt to serious ambiguities on their perception of the healthy food nuances, what may predispose them to highest healthy vs unhealthy orthorexic tendencies. Being torn between the Middle Eastern conflicts and the Western fitness tendencies [33] makes the Lebanese adolescents’ population a curious candidate for ON tendencies’ assessment, especially through a tool that distinguishes the healthy and pathological dimensions of ON, like the TOS. To our knowledge, in the Arabic-speaking populations, there has been no published studies reporting the validation of the TOS, while the ORTO-15 remains the only ON’s questionnaire to be validated in an Arabic version [13]. Hence, the Arabic version of the TOS may be of beneficial use for an appropriate instrument used to measure ON tendencies in the research field and clinical practice. The present study aims to examine the validity and reliability of an Arabic version of the TOS instrument among a sample of Lebanese adolescents.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study enrolled 555 adolescents currently residing in Lebanon (15 to 18 years old), using a proportionate random sample from all Lebanese governorates (May–June 2020). The intention of the study was to distribute a hard copy of the questionnaire to a sample of adolescent with age ranging from 15 to 18 years, reaching to them through their schools. By this time, the coronavirus pandemic outbreak in Lebanon challenged this intended execution of data collection due to nationwide lockdown, imposed social distancing, and schools closing. In order to carry on with this study, snowball sampling and respondent-driven sampling techniques were implemented between May and June 2020. Consequently, a soft copy of the questionnaire was created using google forms software, and an online approach was conceived to proceed with the data collection. Prior to participation, study objectives and general instructions were delivered online for the individual subjects. No credits were received for participation.

Minimal sample size calculation

According to Comrey and Lee [40], the minimal sample size needed to perform a confirmatory factor analysis was 170 based on ten participants for each item scale (TOS scale composed of 17 items).

Questionnaire

The Arabic questionnaire was conceived with three sections: The first section was a written consent, confirming the approval of the adolescents and their parents to fill the questionnaire. The second section constitutes of questions assessing socio-demographic details (age, residency governorate, height, weight, etc.). The Body Mass Index (BMI) was consequently calculated as per the World Health Organization [41]. The household crowding index (HCI), reflecting the socioeconomic status (SES) of the family, was calculated by dividing the number of persons living in the house by the number of rooms in the house; higher HCI reflect a lower SES. The third section included the following scales:

Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS)

This 17-item instrument assesses ON with two separate dimensions [10]: 9 items for Healthy Orthorexia or “HeOr” and 8 items for Orthorexia Nervosa or “OrNe”. Answers are scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (= strongly disagree) to 3 (= strongly agree). Each score by each dimension was computed by summing up the items’ responses. No specific timeframe was asked from the participants while responding. Higher scores reflect more orthorexia nervosa and more healthy orthorexia, respectively. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.853 for the TOS OrNe and 0.829 for the TOS HeOr.

Dusseldorf Orthorexia Scale (DOS)

This scale is composed of ten items aiming at measuring orthorexic behavior [24]; the answers of those items range from 4 = this applies to me to 1 = this does not apply to me, with higher scores reflecting more orthorexic behavior. In this study, αCronbach = 0.849.

ORTO-R

This scale [25] is a revision of the ORTO-15 scale [11], previously validated in Lebanon [13]. It is composed of six items, scored on a four-point Likert scale. Lower scores reflect higher orthorexic tendencies and behaviors. In this study, αCronbach = 0.711.

Forward and back translation procedure

A forward and back translation procedure was implemented. At first, a single bilingual translator, natively Lebanese and fluent in English, conducted the forward translation. A committee of healthcare and language professionals verified the Arabic translated version. A native English speaker translator, fluent in Arabic and unfamiliar with the scales’ concepts, conducted the backward translation to English. Subsequently, the original English questionnaire was compared to the back-translated one by the expert committee. The process was continued until discrepancies and inconsistencies were resolved [42, 43].

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software version 23 was used to conduct data analysis. To assess the internal structure of the TOS scale, we administered the confirmatory factor analysis based on polychoric correlation matrix using Weighted Least Squares with Means and Variance Adjusted estimation (WLSMV) method in Mplus v 7.2 [44] as suggested in the original validation paper [10]. Scales/subscales internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) were also included.

The Student t and ANOVA tests were used to compare two and three or more means respectively. Pearson correlation was used to check for an association between continuous variables. Convergent validity of the TOS scale was assessed via the correlations with the DOS and ORTO-R scales scores. The effect size of the gender on TOS OrNe score was calculated; Cohen suggested that d = 0.2 be considered a small effect size, 0.5 represents a 'medium' effect size and 0.8 a 'large' effect size. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 16.67 ± 1.00 years, with 75.7% females. The mean house crowding index was 0.95 ± 0.50. More details about the students can be found in Table 1. The mean TOS OrNe score was 5.23 ± 4.82 (median = 4; minimum = 0; maximum = 24), whereas the mean TOS HeOr score was 10.15 ± 5.83 (median = 9; minimum = 0; maximum = 27).

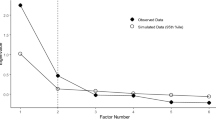

Confirmatory factor analysis

The bi-dimensional model fitted the data well (χ2(118) = 429.09; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.954; RMSEA = 0.069[0.062, 0.076]). The latent factors were highly correlated (ρ = 0.74; p < 0.001), and the strength of the standardized factor loadings (Table 2) was adequate on both factors (i.e., all > 0.60).

Convergent validity

Higher DOS scores were significantly correlated with higher scores on the TOS subscale OrNe (r = 0.715; p < 0.001) as well as with higher scores on the TOS subscale HeOR (r = 0.754; p < 0.001). Same applies for the ORTO-R score; higher ORTO-R scores were significantly associated with less TOS OrNe (r = − 0.437; p < 0.001) and TOS HeOr (r = − 0.305; p < 0.001) scores, respectively.

Factorial validity with the original TOS scale

To assess the degree to which the Lebanese adaptation converges with the original scale, we have conducted the Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MGCFA; estimated as CFA) between the data reported in the current paper and from the original validation paper [10]. Results are reported in Table 3. Accordingly to the conventional criteria of evaluation of the measurement invariance models [45], we have provided evidence of full metric invariance (i.e., the strength of factor loadings is the same in Lebanese and Spanish populations). Furthermore, the fit indices of the scalar model was at the boundary of the threshold; thus, with some pinch of caution, it might be interpreted as invariant (i.e., having equal item intercepts across groups). We have identified latent mean differences in orthorexia nervosa (0.30; p < 0.001), where Spanish individuals scored higher, but we did not find any differences in the healthy eating (0.03; p = 0.636).

Bivariate analysis

Higher age was significantly but weakly associated with lower TOS ON scores (r = − 0.122; p = 0.004), whereas higher BMI was significantly but weakly associated with higher TOS ON scores (r = 0.133; p = 0.002). It is noteworthy that no significant association was found between the household crowding index and TOS ON scores (r = − 0.007; p = 0.862). Moreover, higher TOS ON scores were found in females compared to males (5.58 ± 4.87 vs 4.12 ± 4.49; p = 0.002; Effect size Cohen’s d = 0.311).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous published validation of an Arabic version of the TOS scale, targeting the Lebanese adolescent population. The psychometric properties of the TOS were rarely discussed in the literature, due to the lack of studies that used the TOS to assess ON tendencies and behaviors, so far [46]. However, we found a single study conducted in 2020 [47] that investigated the psychometric properties of the English version of the TOS and emphasized the superiority of the TOS’ psychometrics over other ON’s measuring instruments. In fact, the TOS is considered to be a highly promising instrument by its ability to distinguish between HeOr and OrNe [10, 18, 48]. Thus, the aim of the current study was to examine the validity and reliability of an Arabic version of the TOS instrument among a sample of Lebanese adolescents.

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) that we conducted yielded to a 17-item version of the TOS, for which the two-factor solutions showed satisfactory goodness-of-fit similar to the original scale [10]. Satisfactory values of internal consistency were found as well, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.853 and 0.829 for the HeOr and OrNe subscales, respectively. The latter values are considered supportive of the Cronbach’s alpha values found in the original Spanish version of the TOS (above 0.8 for both HeOr and OrNe [10]). On a side note, these two coefficients emphasized the original, as well as, the current relatively high correlation between the sub-scales of the TOS, suggesting a consequent similarity in the measurement of HeOr and OrNe. This would draw the question of whether these two subscales are measuring the same aspect of ON; further studies and investigations are needed to tackle this question.

Furthermore, while assessing the degree to which the Lebanese adaptation of the TOS converges with the scale’s original Spanish version, the fit indices of the scalar model could be interpreted, to some extent, as invariant, in addition to the full metric invariance that we already found in the MGCFA. This evidence of invariance in terms of the bi-dimensional structure of the TOS and the factor loadings and intercepts highlights the strength of this Arabic version of the TOS, in its similitudes to the original Spanish version, even while comparing two different populations: Lebanese adolescents vs. Spanish adults [10]. However, this cross-cultural difference could be manifesting itself by a latent difference regarding results of the OrNe and not the HeOr, where Spanish adults from the original study, scored higher for OrNe and not for HeOr, in comparison to the current Lebanese adolescents sample [10]. From a sociodemographic perspective, many explanations would elicit the emergence of this difference. While both the Spanish and Lebanese food tables are thought to be inspired by the traditional Mediterranean diet, the adherence to this WHO-recommended diet has changed between these two countries [49]. In fact, to a lesser extent than the middle eastern countries, the European Mediterranean countries are succumbing to a westernization process of their diet [49, 50], affected by social, political and cultural changes. Southwestern European countries, such as Spain, Greece, and Italy [50], were the most prone to this decrease in Mediterranean diet adherence, due to changes in food availabilities and westernized dietary policies. On the other hand, a major common pattern that affects both the Lebanese and Spanish dietary models but on different terms is the socio-economic instability in both countries, where social classes inequalities [39, 51] make a profound gap in the adherence to the international dietary guidelines. Examples of recent and close socio-economic crises that affected both countries would be the 2008–2014 Spanish financial crisis [51], and the current 2019 Lebanese economic/financial crisis, where the perception and adherence to healthy dietary styles were profoundly shaken in both countries. Thus, all these diversified factors would explain the close similarities, and yet latent differences, between the Lebanese and Spanish populations’ perception of healthy food, and consequently orthorexic behaviors.

Moreover, the item-total correlations were high for most items, with a well-demonstrated convergent validity with the DOS scale. Hence, this makes the current Arabic version of the TOS a reliable instrument to assess ON’s tendencies and behaviors among Lebanese adolescents.

In terms of validity, the TOS OrNe subscale score significantly and positively correlated with the DOS score, supporting the convergent validity of the TOS. Nevertheless, the TOS HeOr subscale, known for its evaluation of non-pathological feature of healthy eating [52], correlated with DOS as well. Due to the lack of studies investigating the DOS–TOS association so far, conclusions must be drawn with caution. Future studies are need to clearly differentiate between the two constructs of “orthorexia nervosa” and “healthy orthorexia”.

In the current study, older age was weakly associated with lower TOS scores, thus less ON tendencies and behaviors. Another study as well [37] showed relatively similar results, where junior school-age youth was associated with higher ON tendencies compared to the senior school-age and university-age youth groups. This negative correlation between age and ON tendencies can be explained by the fact that younger adolescents, being at their early puberty period, are considered at their most vulnerable state facing the turbulent phase of dissatisfaction with their own body [3, 37]. They make frequent attempts to change their own appearance, implement diets without reliable knowledge about the principles of proper nutrition [37, 53].

Higher BMI was significantly but weakly associated with higher TOS scores, hence more ON tendencies. However, on the one side, orthorexia nervosa is thought to be related to food quality control rather than quantity control (unlike anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders), with previous findings having revealed little or no correlation between body mass index (BMI) and ON [10]. On the other side, other findings showed that higher BMI in adolescents was associated with higher orthorexic behaviors [54, 55]. Although orthorexia nervosa is thought to be related to food quality control rather than quantity control (unlike anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders), it is possible that overweight/obese subjects would adopt orthorexic strategies to achieve the accurate and healthy BMI, rather than the thin or good looking BMI, satisfying their obsession for wellness [55]. The weak correlations between ON and age and BMI require a cautious interpretation of the current results, as well as further studies to better explore these correlations.

Higher TOS scores were found in females compared to males. Despite the fact that no or small gender differences were found between male and female groups regarding ON tendency rates [30, 56, 57], many ON-related studies revealed the same problem as our sampling scheme, where females are more represented than males (76.1% of our participants are females) [58, 59]. However, aside from ON, disordered eating in general was found to be more susceptible in Lebanese female adolescents where concerns for healthy body image are of a higher grade than in male Lebanese adolescents [60]. However, further studies are needed to explore this relationship: gender–ON.

What is already known on this subject?

What does this study add?

In a sample of Lebanese adolescents, the TOS Arabic version seems to be a validated and reliable tool for ON assessment, what it may add to the literature what it lacked concerning the reliability and the validity of the TOS instrument.

Limitations and strengths

No causality can be inferred from this cross-sectional study. The DOS scale was not validated in the Arabic language yet. The orthorexic tendencies and behaviors were measured using a scoring instrument and not through a clinical patient–specialist interview; therefore, the accuracy of responses could not be confirmed. In fact, the TOS validity and use in the literature remain limited despite being a more promising instrument than any other, in terms of better internal consistency. Further assessment by a psychiatrist, a psychologist, and a qualified specialist may be needed to confirm the obtained results. The snowball sampling technique was used because of the challenging execution of data collection in Lebanon in the time of COVID-19 related lockdown; therefore, our data might not be generalizable. In our sample, female participants were more numerically represented than male participants. On another side, the used sample size is considerably large enough for the Lebanese high school population. Although, self-reported scales continue to be the most commonly used tools in epidemiological studies on disordered eating, the use of questionnaire can lead to information bias due to possible problems in understanding the questions and over-estimation / under-estimation of symptoms that may lead to inaccuracy. Obsessive–compulsive tendency and anorexic tendencies were not evaluated in the current study.

Conclusion

The values acquired from the validation and adaptation of the Arabic version of the TOS questionnaire were relatively acceptable. Hence, this Arabic version can be considered a valuable and reliable tool to assess the presence of orthorexic behaviors and tendencies in Lebanese adolescents, emphasizing the fine contrast between ON’s two dimensions: healthy vs. pathological. The evident numerous similarities, despite the few latent differences, that were found between the original Spanish version of the TOS and this current Arabic version, would draw the attention of the literature for the need of future studies that would re-interpret the ON’s measurement tools from the perspective of cross-cultural differences.

References

Bratman S, Knight D (1997) Health food junkie. Yoga journal 136:42–50

Koven NS, Abry AW (2015) The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11:385–394

Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C (2004) Orthorexia nervosa: a preliminary study with a proposal for diagnosis and an attempt to measure the dimension of the phenomenon. Eat Weight Disord 9:151–157

Gramaglia C, Brytek-Matera A, Rogoza R, Zeppegno P (2017) Orthorexia and anorexia nervosa: two distinct phenomena? A cross-cultural comparison of orthorexic behaviours in clinical and non-clinical samples. BMC Psychiatry 17:75

Bratman S, Knight D (2000) Health food junkies: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating, Broadway Books

Cuzzolaro M, Donini LM (2016) Orthorexia nervosa by proxy? Eat Weight Disord 21:549–551

Cena H, Barthels F, Cuzzolaro M, Bratman S, Brytek-Matera A, Dunn T, Varga M, Missbach B, Donini LM (2019) Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: a narrative review of the literature. Eat Weight Disord 24:209–246

Missbach B, Dunn TM, Konig JS (2017) We need new tools to assess Orthorexia Nervosa. A commentary on "Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa among College Students Based on Bratman’s Test and Associated Tendencies. Appetite 108:521–524

Roncero M, Barrada JR, Perpina C (2017) Measuring orthorexia nervosa: psychometric limitations of the ORTO-15. Span J Psychol 20:E41

Barrada JR, Roncero M (2018) Estructura Bidimensional de la Ortorexia: Desarrollo y Validación Inicial de un Nuevo Instrumento. Anales de Psicología 34:282–290

Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C (2005) Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord 10:e28-32

Mosticoni R., Chiari G (1979) Una descrizione obiettiva della personalità: il" Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory",(MMPI), Organizzazioni Speciali.

Haddad C, Hallit R, Akel M, Honein K, Akiki M, Kheir N, Obeid S, Hallit S (2020) Validation of the Arabic version of the ORTO-15 questionnaire in a sample of the Lebanese population. Eat Weight Disord 25:951–960

Arusoğlu G, Kabakçi E, Köksal G, Merdol TK (2008) Orthorexia Nervosa and Adaptation of ORTO-11 into Turkish. Turkish J Psychiatry 19:2008

Brytek-Matera A, Krupa M, Poggiogalle E, Donini LM (2014) Adaptation of the ORTHO-15 test to Polish women and men. Eat Weight Disord 19:69–76

Missbach B, Hinterbuchinger B, Dreiseitl V, Zellhofer S, Kurz C, Konig J (2015) When eating right, is measured wrong! A validation and critical examination of the ORTO-15 questionnaire in German. PLoS ONE 10:e0135772

Parra-Fernandez ML, Rodriguez-Cano T, Onieva-Zafra MD, Perez-Haro MJ, Casero-Alonso V, Munoz Camargo JC, Notario-Pacheco B (2018) Adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the ORTO-15 questionnaire for the diagnosis of orthorexia nervosa. PLoS ONE 13:e0190722

Depa J, Barrada JR, Roncero M (2019) Are the motives for food choices different in orthorexia nervosa and healthy orthorexia? Nutrients 11:697

Varga M, Thege BK, Dukay-Szabo S, Tury F, van Furth EF (2014) When eating healthy is not healthy: orthorexia nervosa and its measurement with the ORTO-15 in Hungary. BMC Psychiatry 14:59

Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E, Burgalassi A, Conversano C, Massimetti G, Dell’Osso L (2011) Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord 16:e127-130

Heiss S, Coffino JA, Hormes JM (2019) What does the ORTO-15 measure? Assessing the construct validity of a common orthorexia nervosa questionnaire in a meat avoiding sample. Appetite 135:93–99

Alvarenga MS, Martins MC, Sato KS, Vargas SV, Philippi ST, Scagliusi FB (2012) Orthorexia nervosa behavior in a sample of Brazilian dietitians assessed by the Portuguese version of ORTO-15. Eat Weight Disord 17:e29-35

Gleaves DH, Graham EC, Ambwani S (2013) Measuring “orthorexia”: development of the Eating Habits Questionnaire. Int J Educ Psychol Assess 12(2):1–18

Barthels F, Meyer F, Pietrowsky R (2015) Die Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala-Konstruktion und Evaluation eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung ortho-rektischen Ernährungsverhaltens. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000310

Rogoza R, Donini LM (2020) Introducing ORTO-R: a revision of ORTO-15: based on the re-assessment of original data. Eat Weight Disord 26:887–895

Abdullah MA, Al Hourani HM, Alkhatib B (2020) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among nutrition students and nutritionists: Pilot study. Clin Nutr ESPEN 40:144–8

Sfeir E, Haddad C, Salameh P, Sacre H, Hallit R, Akel M, Honein K, Akiki M, Kheir N, Obeid S, Hallit S (2019) Binge eating, orthorexia nervosa, restrained eating, and quality of life: a population study in Lebanon. Eat Weight Disord 26:145–158

Haddad C, Obeid S, Akel M, Honein K, Akiki M, Azar J, Hallit S (2019) Correlates of orthorexia nervosa among a representative sample of the Lebanese population. Eat Weight Disord 24:481–493

Farchakh Y, Hallit S, Soufia M (2019) Association between orthorexia nervosa, eating attitudes and anxiety among medical students in Lebanese universities: results of a cross-sectional study. Eat Weight Disord 24:683–691

Strahler J, Haddad C, Salameh P, Sacre H, Obeid S, Hallit S (2020) Cross-cultural differences in orthorexic eating behaviors: associations with personality traits. Nutrition 77:110811

Kattan AM (2016) The prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in Lebanese university students and the relationship between orthorexia nervosa and body image, body weight and physical activity. J Psychopathol 24(3):133–140

Obeid S, Hallit S, Akel M, Brytek-Matera A (2021) Orthorexia nervosa and its association with alexithymia, emotion dysregulation and disordered eating attitudes among Lebanese adults. Eat Weight Disord 11:1–10

Yannakoulia M, Matalas AL, Yiannakouris N, Papoutsakis C, Passos M, Klimis-Zacas D (2004) Disordered eating attitudes: an emerging health problem among Mediterranean adolescents. Eat Weight Disord 9:126–133

Babaei S, Alizadeh L (2020) Relationship between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and body image with eating disorder symptoms in secondary school students.

Hyrnik J, Janas-Kozik M, Stochel M, Jelonek I, Siwiec A, Rybakowski JK (2016) The assessment of orthorexia nervosa among 1899 Polish adolescents using the ORTO-15 questionnaire. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 20:199–203

Duran S (2016) The risk of orthorexia nervosa (healthy eating obsession) symptoms for health high school students and affecting factors. Pamukkale Med J 9:220–226

Lucka I, Domarecki P, Janikowska-Holowenko D, Plenikowska-Slusarz T, Domarecka M (2019) The prevalence and risk factors of orthorexia nervosa among school-age youth of Pomeranian and Warmian-Masurian voivodeships. Psychiatr Pol 53:383–398

Nabhani-Zeidan M, Naja F, Nasreddine L (2011) Dietary intake and nutrition-related knowledge in a sample of Lebanese adolescents of contrasting socioeconomic status. Food Nutr Bull 32:75–83

Nasreddine L, Hwalla N, Sibai A, Hamze M, Parent-Massin D (2006) Food consumption patterns in an adult urban population in Beirut. Lebanon Public Health Nutr 9:194–203

Comrey AL, Lee HB (2013) A first course in factor analysis. Psychology Press, Hove

World Health Organizaiton: Body Mass Index. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25:3186–3191

Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB (2002) Recommendations for the cross-cultural adaptation of health status measures. New York Am Acad Orthopaed Surg 12:1–9

Muthén LK, Muthén B.O. (1998–2012). Mplus User’s Guide, Seventh Edition. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Chen FF (2007) Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ Modeling 14:464–504

Valente M, Syurina EV, Donini LM (2019) Shedding light upon various tools to assess orthorexia nervosa: a critical literature review with a systematic search. Eat Weight Disord 24:671–682

Chace S (2020) Orthorexia Nervosa: Validation of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale and Relationship to Health Anxiety

Parra-Fernandez ML, Rodriguez-Cano T, Onieva-Zafra MD, Perez-Haro MJ, Casero-Alonso V, Fernandez-Martinez E, Notario-Pacheco B (2018) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in university students and its relationship with psychopathological aspects of eating behaviour disorders. BMC Psychiatry 18:364

da Silva R, Bach-Faig A, Raido QB, Buckland G, Vaz de Almeida MD, Serra-Majem L (2009) Worldwide variation of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, in 1961-1965 and 2000-2003. Public Health Nutr 12:1676–1684

Blas A, Garrido A, Unver O, Willaarts B (2019) A comparison of the Mediterranean diet and current food consumption patterns in Spain from a nutritional and water perspective. Sci Total Environ 664:1020–1029

Diaz-Mendez C, Garcia-Espejo I (2019) Social inequalities in following official guidelines on healthy diet during the period of economic crisis in spain. Int J Health Serv 49:582–605

Barrada JR, Roncero M (2018) Bidimensional structure of the orthorexia: development and initial validation of a new instrument. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology 34:283–291

Sukariyah MB, Sidani RA (2014) Prevalence of and gender differences in weight, body, and eating related perceptions among Lebanese high school students: Implications for school counseling. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 159:184–191

Oberle CD, Samaghabadi RO, Hughes EM (2017) Orthorexia nervosa: assessment and correlates with gender, BMI, and personality. Appetite 108:303–310

Hyrnik J, Janas-Kozik M, Stochel M, Jelonek I, Siwiec A, Rybakowski JK (2016) The assessment of orthorexia nervosa among 1899 Polish adolescents using the ORTO-15 questionnaire. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 20:199–203

Brytek-Matera A, Sacre H, Staniszewska A, Hallit S (2020) The prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in polish and lebanese adults and its relationship with sociodemographic variables and bmi ranges: a cross-cultural perspective. Nutrients 12(12):3865

Brytek-Matera A, Staniszewska A, Hallit S (2020) Identifying the profile of orthorexic behavior and “normal” eating behavior with cluster analysis: a cross-sectional study among polish adults. Nutrients 12:3490

Barrada JR, Ruiz-Gomez P, Correa AB, Castro A (2019) Not all online sexual activities are the same. Front Psychol 10:339

Barrada JR, Castro A, Correa AB, Ruiz-Gomez P (2018) The Tridimensional Structure of Sociosexuality: Spanish Validation of the Revised Sociosexual Orientation Inventory. J Sex Marital Ther 44:149–158

Yahia N, El-Ghazale H, Achkar A, Rizk S (2011) Dieting practices and body image perception among Lebanese university students. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 20:21–28

Acknowledgements

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge every participant who helped them accomplish this study. A great appreciation and a thank you from the heart goes to Dr. Radoslaw Rogoza for his help in the statistical analysis and comments.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare not having any conflicts of interest to report in this study.

Ethical approval

The Ethics and Research Committee of the Psychiatric Hospital of the Cross approved this study protocol (HPC-035–2020). Students were asked to get their parents’ consent before filling the survey. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mhanna, M., Azzi, R., Hallit, S. et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS) among Lebanese adolescents. Eat Weight Disord 27, 619–627 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01200-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01200-w