Abstract

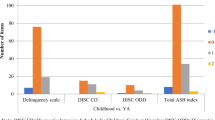

Maternal report of types of conduct problems in a high-risk sample of 228 boys and 80 girls (ages 4–18) were examined, using a version of the Child Behavior Checklist, expanded to include a range of covert and overt antisocial items (stealing, lying, physical aggression, relational aggression, substance use, and impulsivity). Age and sex effects were investigated. Boys were significantly more physically aggressive than girls. There were no sex differences for stealing, lying, relational aggression, and substance use. Lying and substance use increased with age, whereas relational aggression and impulsivity peaked during early adolescence. A small group of girls had pervasive conduct problems across multiple domains. For some domains such as stealing, lying, and relational aggression, girls showed at least as many problems as boys. Girls, in general, tended to have fewer conduct problems. On the other hand, when assessed across multiple domains, conduct problems in high-risk girls were possibly more pervasive than in high-risk boys, suggesting the possibility of a gender paradox.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the CBCL/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1983). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1986). Manual for the Teacher's Report Form and Teacher Version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition. Washington DC: APA Press.

Ciocco, A. (1940). Sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Quarterly Review of Biology, 15 59-92.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (rev. ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children's future social adjustment. Child Development, 67 2317-2327.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66 710-722.

DeFries, J. (1989). Gender ratios in children with reading disability and their affected relatives: A commentary. Journal of Learning Disability, 22 544-545.

Earls, F. (1987). Sex differences in psychiatric disorders: Origins and developmental influences. Psychiatric Developments 1 1-23.

Eme, R. F. (1979). Sex differences in childhood psychopathology: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 86 574-595.

Eme, R. F. (1992). Selective female affliction in the developmental disorders of childhood: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21 354-364.

Hays, W. L. (1963). Statistics. New York, NY: Holt, Rhinehart & Winston.

Hyde, J. S. (1986). Gender differences in aggression. In J. S. Hyde & M. C. Linn (Eds.), The psychology of gender: Advances through meta-analysis. pp 51-66. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

James, A., & Taylor, E. (1990). Sex differences in the hyperkinetic syndrome of childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31 437-446.

Kazdin, A. E. (1992). Overt and covert antisocial behavior: Child and family characteristics among psychiatric inpatient children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1 3-20.

Kazdin, A. E. (1993). Adolescent mental health: Prevention and treatment programs. American Psychologist, 48 127-141.

Lagerspetz, K. M. J., & Bjorkqvist, K. (1994). Indirect aggression in boys and girls. In L. R. Huesmann (Ed.), Aggressive behavior: Current perspectives (pp. 131-150). New York: Plenum Press.

Lagerspetz, K. M. J., Bjorkqvist, K., & Peltonen, T. (1988). Is indirect aggression typical of females? Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11-to 12-year-old children. Aggressive Behavior, 14 403-414.

Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Van Kammen, W. B. (1998). Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Loeber, R., & Keenan, K. (1994). Interaction between conduct disorder and its comorbid conditions: Effects of age and gender. Clinical Psychology Review, 14 497-523.

Loeber, R., & Schmaling, K. B. (1985). The utility of differentiating between mixed and pure forms of antisocial child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 13 315-335.

Maccoby, E. E. (1986). Social groupings in childhood: Their relationship to prosocial and antisocial behavior in boys and girls. In D. Olweus, J. Block, & M. Radke-Yarrow (Eds.), Development of antisocial and prosocial behavior (pp. 263-284). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1974). The psychology of sex differences. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1980). Sex differences in aggression: A rejoinder and reprise. Child Development, 51 964-980.

McDermott, P. A. (1996). A nationwide study of developmental and gender prevalence for psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24 53-66.

McGee, R., Silva, P. A., & Williams, S. (1984). Behaviour problems in a population of seven-yearold children: Prevalence, stability and types of disorder-A research report. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25 251-259.

Murray, D. M., & Wolfinger, R. D. (1994). Analysis issues in the evaluation of community trials: Progress toward solutions in SAS/STAT MIXED. Journal of Community Psychology, Special Issue, 140-154.

Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., Szatmari, P., Rae-Grant, N. I., Links, P. S., Cadman, D. T., Byles, J. A., Crawford, J. W., Blum, H. M., Byrne, C., Thomas, H., & Woodward, C. A. (1987). Ontario Child Health Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44 832-836.

Robins, L. (1966). Deviant children grow up. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Robins, L. (1991). Conduct disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 32 193-213.

Rotenberg, K. J. (1985). Causes, intensity, motives, and consequences of children's anger from self-reports. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 146 101-106.

Rutter, M. (1990). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In J. Rolf, A. S. Masten, D. Cicchetti, K. H. Nuechterlein, & S. Weintraub (Eds.), Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology (pp. 181-214). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SPSS 9.0. (1997). Chicago, Illinois: SPSS, Inc.

Statistical Analysis System (1991). The MIXED Procedure, Technical Report P-229, SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements, Release 6.07 (pp. 289-366). Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute Inc.

Wasserman, G. A., Miller, L. S., Pinner, E., & Jaramillo, B. (1996). Parenting predictors of early conduct problems in urban, high-risk boys, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35 1227-1236.

Werner, E. E., & Smith, R. S. (1982). Vulnerable but invincible: A study of resilient children. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Werner, E. E., & Smith, R. S. (1992). Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Zoccolillo, M. (1993). Gender and the development of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 5 65-78.

Zoccolillo, M., Tremblay, R., & Vitaro, F. (1996). DSM-III-R and DSM-III criteria for Conduct Disorder in preadolescent girls: Specific but insensitive. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35 461-470.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tiet, Q.Q., Wasserman, G.A., Loeber, R. et al. Developmental and Sex Differences in Types of Conduct Problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies 10, 181–197 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016637702525

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016637702525