Abstract

Background and objectives

Describe the financial burden and worry that families of preterm infants experience after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Methods

We surveyed 365 parents of preterm infants in a cross-sectional study regarding socio-demographics, supplemental security income (SSI), and financial worry. We completed a multivariable logistic regression model to examine the adjusted association of financial worry with modifiable factors.

Results

We found that 53% of participants worried about healthcare costs after NICU discharge. After adjusting for socio-demographic and infant characteristics, we identified that, aOR (95% CI), out-of-pocket costs from the NICU index hospitalization, 3.51 (1.7, 7.26) and durable medical equipment use, 2.41 (1.11, 5.23) was associated with increased financial worry while enrollment in SSI, 0.38 (0.19, 0.76) was associated with decreased financial worry.

Conclusions

We identified factors that could contribute to financial burden after NICU discharge that may advise future work to target financial support systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

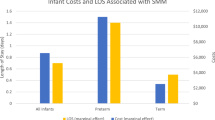

Preterm and low-birth weight infants account for half of infant hospitalization costs and a quarter of all pediatric healthcare costs [1]. While hospitalization-related costs of preterm birth have been well studied [2], much less is known about the categories of economic burden and prevalence of financial worry faced by families of preterm infants after taking their infant home from the hospital [3].

Recognizing a paucity of data on financial aspects of preterm birth from the parent perspective, some authors have called for research to assess out-of-pocket family costs and lost productivity associated with preterm birth [4]. The 2007 Institute of Medicine report on Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences and Prevention stressed the importance of assessing aspects of familial economic burden [2]. The UK Nuffield Report on Bioethics noted that: “Economic studies of premature birth and low-birth weight have tended to overlook the costs, for example, of day-care services and respite care, as well as those borne by the local authorities, voluntary organizations and by families as a result of modifications of their everyday activities” [5]. One study evaluated an intervention to improve referrals to a health benefits coordinator to mitigate the financial burden after discharge [6]. In 2014, a study from Canada attempted to include productivity losses by caregivers of preterm infants as well as prenatal costs, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) hospitalization and special education, finding an average cost of CAD $88,988 per patient over the first year of life, but the study did not explicitly break down the non-medical costs such as nutrition, housing, or transportation [7]. In a thoughtful commentary on exploration of caregiver costs in the literature, Zupancic reviewed evaluations nested within other studies [8] and identified that median out-of-pocket costs during infant hospitalization ranged from $424/week [9] (questionnaire-based study about respiratory support) to $1000/week in the DOMINO trial (a study where infants were randomized to donor breast milk) [10].

Thus, despite widespread recognition that the true financial burden associated with caring for infants discharged from the NICU has not been adequately captured, few studies exist that have actually tracked non-medical expenses or even the categories of expenses incurred by these families. In the US, studies that capture healthcare spending and utilization after NICU discharge do not quantify indirect costs [11,12]; surveying the literature, only a few papers, all written in the last 20 years, focus on the financial and economic burden of families of NICU graduates. The aims of our study were to describe the categories of financial burden and prevalence of financial worry that families of preterm infants experience after discharge from the NICU and identify modifiable factors that are associated with financial worry.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional survey-based study. We enrolled caregivers of preterm (<37 weeks’ gestation) infants up to 24 months’ corrected age, attending outpatient follow up clinics at two large tertiary urban children’s hospitals. Data were collected at Boston Children’s Hospital in 2011–2012 and at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles from 2013–2015. Families were excluded if the infant was >24 months corrected age, the families were not interested, missed for referral to the study or not English- or Spanish speaking. A 150-item questionnaire with components validated in English and Spanish was administered to participants about life after discharge from the NICU. Patient recruitment, survey administration and population characteristics are detailed in previous work [13,14,15]. The Boston Children’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles human subjects committees approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures of financial burden

We asked six questions from the 2007 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey [16,17,18,19] regarding unexpected costs, increased bills, increased out-of-pocket expenses, and financial worry. In addition, we asked families about their employment, compensation for time off from work, costs related to travel for appointments, care for siblings, and receipt of supplemental security income (SSI) assistance during and/or after the baby’s hospitalization. Each question was answered with a yes/no response. Compensation structures if employed were presented as number of responses and participants could indicate more than one response.

Use of community-based resources

Participants were asked about the use of community-based developmental resources (e.g., early intervention programs), use of social services, such as food assistance programs, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Women, Infant, Children’s program, energy assistance/disability programs like the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, Transitional Aid to Families with Dependent Children, and receipt of SSI.

Health-related social problems

HelpSteps© is a web-based survey instrument designed to identify health-related social problems. We administered the 25-item survey, which includes questions about family income, race/ethnicity, housing, tobacco exposure, insurance status, and home safety [20,21,22]. An unsafe home was described as one with water leaks, pests, or no heat. We also noted differences between our cohorts.

Infant health and development

We obtained information from the medical record regarding delivery and complications during the neonatal hospitalization (“predisposing characteristics”). We also asked parents questions about their infant’s health status since discharge including the number of emergency department visits, number of monthly clinic appointments, number of hospitalizations, immunizations, dependence on durable medical equipment, and administration of prescription medications (“post-discharge” characteristics). To assess infant development, we used the Motor and Social Development scale [23], which we have previously validated in our population [24]. Parents responded to 15 age-appropriate questions and we calculated standard scores based on national normative standards.

Statistical analysis

We calculated frequencies and proportions to describe the sample population. Multivariable logistic regression estimated the adjusted odds of financial worry (often and sometimes vs. never). The model was adjusted for confounders such as race/ethnicity, income, geographic location, gestational age (weeks), chronologic age (months), use of prescription medications, use of medical equipment, attribution to the NICU index hospitalization, enrollment in SSI, time taken off work, childcare and cost conversations. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and two-sided p values for individual variable categories are reported.

Power calculation

For a one sample study with a dichotomous endpoint (financial worry vs. no financial worry), a sample size of at least 240 is needed to achieve 80% power to reject the null hypothesis when the population vs. sample difference in incidence of financial worry is ten percent (previous literature vs. this sample) with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05 (summary statement generated in PASS).

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for analyses. Data and computer code are available upon request with no restrictions.

Results

Patient recruitment is described in Fig. 1. As outlined in Table 1, most participants were mothers (83%). Almost half (46%) of the sample reported annual incomes <$40,000/year and 40% responded their primary language was not English. Most (64%) utilized Medicaid and 91% used at least one social service (food security, income, home energy). Median (IQR) birth weight, gestational age, and chronologic age at the time of participation were 950 grams (710, 1385), 28 weeks (26, 31) and 10 months (7, 17). More than half of the infants had at least one neonatal co-morbidity (58%) including fetal growth restriction, necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or 4, patent ductus arteriosus, or retinopathy of prematurity. The majority (71%) had more than two clinical appointments/month, 20% used durable medical equipment and 60% received at least one prescription medication daily.

We assessed time off work, costs of care, and supplemental income (Table 2). More than 40% of participants had taken time off work; of those, 50 out of 187 response (27%) indicated time off without pay. Similarly, 55% of their partners had taken time off work; of those, 75 out of 215 responses (35%) marked time off without pay. Twenty-six percent of family and friends had also taken time off to help with the participant’s family, 10 out of 96 (10%) indicated time without pay. While 55% had discussed enrollment in SSI prior to discharge from the NICU if eligible, only 23% were enrolled at the time of participation. Of those, 92% received <$1000/month.

We queried families about financial worry and out-of-pocket costs (Table 2). Almost a third (29%) reported unexpected events that raised medical costs; 69% of those attributed this to the baby’s NICU hospitalization. In total, 18% reported problems paying for medical bills; 63% attributed this to the baby’s hospitalization. In total, 36% reported higher than expected out-of-pocket costs. In total, 23% of participants used savings to pay for medical costs and 9% had bills sent to collections. While 53% of participants worried about health costs (“sometimes or often”), only 26% discussed costs of care with staff while hospitalized in the NICU and only 19% discussed costs of care with their pediatrician.

As seen in Fig. 2A, almost 80% of families traveled to follow up appointments in the month prior to participation, of which 84% traveled by car and incurred parking charges. Figure 2B outlines childcare expenses; 14% had hired childcare to babysit siblings and 61% of those had spent at least $100 per week in the last month to do so.

Supplementary Material presents differences between our cohorts in Boston vs. Los Angeles (LA) in terms of ethnicity, income, education and language and financial worry (Supplementary Material, Tables 1–3). Supplementary Material Table 4 presents associations of use of SSI, cost conversations, and leave from work with financial worry. Sixty percent of participants who received SSI reported “never” being worried about healthcare costs vs. only 31% of those who did not receive SSI.

A multivariable regression that examined the association between modifiable factors and financial worry is presented in Table 3. After adjusting for socio-demographic, infant and financial characteristics, we identified that, aOR (95% CI), out-of-pocket expenses from the NICU index hospitalization, 3.51 (1.7, 7.26), p = 0.0007, and durable medical equipment use, 2.41 (1.11, 5.23), p = 0.03 was associated with increased financial worry (sometimes or often vs. never), while enrollment in SSI, 0.38 (0.19, 0.76), p = 0.006 was associated with decreased financial worry independent of gestational or chronologic age. Differences in the cohorts are presented in Supplementary Material Tables 5a, b; only the expenses from the infant’s NICU hospitalization was associated with financial worry in the stratified analysis.

Discussion

In this study, we found that more than half of families with preterm infants experienced financial worry after NICU discharge and that the out-of-pocket expenses from the index NICU hospitalization and durable medical equipment use was associated with increased financial worry, while enrollment in SSI was associated with decreased financial worry. Of note, while we had a bi-coastal sample that had different socio-demographics and employment/paid leave patterns, the frequency of financial worry was similar. We also found that less than a third of the sample was enrolled in SSI at the time of participation and only a fraction held cost conversations with staff while hospitalized in the NICU or after discharge. We also identified several areas where added costs or lost wages contributed to the financial burden for families after discharge such as lack of pay with time taken off, direct medical costs during follow-up, childcare for siblings and out-of-pocket expenses. We must integrate targeted financial support systems for families while they are in the NICU, as they transition to home and after discharge.

We identified that unexpected out-of-pocket costs due to the NICU index hospitalization and use of durable medical equipment was associated with increased financial worry. Children with medical complexity make up most of pediatric hospitalization expenditures [25]. Most of our sample had complex chronic conditions and many required durable medical equipment or prescription medications, both of which can be associated with financial burden and out-of-pocket expenditures as identified in previous work [4,26,27,28]. This cost component may contribute to increased parental and family strain. Improved care coordination within the family-centered medical home or family navigation programs could reduce the impact for these children with special health care needs by identifying alternative sources of payment for needed services [29,30,31,32].

We found that enrollment in SSI was associated with decreased financial worry. However, only a fraction of families were enrolled even if eligible. The SSI program provides cash assistance to low-income people with substantial disabilities. The usual income support is about $6000 per year; this money can be used for any need that a child may have. Current presumptive eligibility criteria include a birth weight of <1200 grams for a child claimant <1 year of age or being small for gestational age, with a planned reevaluation at 12 months of age to determine ongoing clinical severity. Per the 2020 SSI report, 11,706 cases were reviewed with 45% funded for the receipt of SSI in 2019 under the presumptive eligibility criterion of a birth weight of <1200 grams [33]. While the program is well supported for families of premature infants, few studies have actually examined its effects on financial burden for families themselves. Other pediatric populations, including those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and cancer, have demonstrated some benefit of SSI for families of children with disabilities [34, 35]. Our study affirms that enrollment in SSI also is associated with a lower odds of financial worry in a population of families with preterm infants. In our sample like many others, families faced barriers in enrollment or knowledge about the program [36]. More resources should be provided to strengthen the infrastructure in NICUs (for example, to social workers) to help screen, inform, and enroll families in SSI.

Data collection in this study coincided with the peak of implementation of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA was designed to reduce the number of uninsured, make healthcare affordable, and improve health outcomes [37]. Unfortunately, children and children with special health care needs (such as preterm infants after NICU discharge) were not a priority in the design of the ACA. Issues that surfaced after implementation include limitations on grandfathered plans, the nature of accountable care organizations for children and the application of Health Homes for children [37]. Another important consideration that emerged was underinsurance—a phenomenon when children live in families that cannot afford clinician recommended care (subspecialty appointments, filling prescriptions, etc.) despite having health insurance [38,39,40]. While the number of uninsured children declined post-ACA, the number of underinsured children remained the same or even increased in some areas [40]. In this sample, on multivariable analysis, use of durable medical equipment (implying that the child had special health care needs) independent of epoch of data collection post-ACA (2011–2012 vs. 2013–2015) and geographic location were not significant variables for financial worry. Pascoe et al. identified that lower income families (annual incomes $15,000–$34,999) with children with special health care needs with private insurance were more likely to be underinsured than lower income families with children with special health care needs with public insurance [40]. Low-income families with private insurance and particularly high-deductible health plans are subject to financial strain given risks for unemployment and depletion of savings [41] with out-of-pocket expenses [41, 42]. More recent work since the close of data collection for this study and the COVID-19 pandemic [43] have shifted the social safety-net for families with children with special health care needs and more families have found their children underinsured [40]. This suggest that a higher proportion of families would have financial worry than represented in this sample if data collection was more recent. Policymakers could mitigate some of the financial burden faced by low-income families by incorporating wage support and to low and middle-income families with private insurance by offering health exchanges with cost-calculators and price transparency tools to provide families with more information when choosing health plans [44].

While there has been some work regarding facilitating cost conversations in previous studies [45], little has been done to evaluate the burden of care for families once an infant has been discharged from the NICU. Beck et al. completed a qualitative study among pediatric patients’ families to examine how they would like to discuss costs of care [46]. Most wanted to discuss insurance status and out-of-pocket costs in the inpatient setting and preferred for physicians to initiate the conversation but a financial counselor to actually conduct the session. Moreover, families suggested cost discussion should take place when a child is medically stable and occur in person at the bedside with supplemental written materials and should be optional for families. We hypothesized that discussing costs in the NICU or with the pediatrician would be associated with decreased financial worry. While a higher proportion of families who reported less financial worry had cost conversations with their providers, having conversations was not associated with less financial worry on the adjusted multivariable model. Rather, independent of having cost conversations, enrollment in SSI was associated with decreased financial worry. These results suggest that families may appreciate initiating discussions about cost with their provider but immediate cash benefit financial assistance might be even more useful.

In this study, we presented a bi-coastal sample from two urban children’s hospitals in California and Massachusetts. There were marked differences between participants including demographics, employment, and wage losses. There significant differences in employment between samples (a much larger portion were unemployed in Los Angeles) suggesting there may issues related to maintaining employment rather than wage losses in Boston. Perhaps more participants in the Los Angeles cohort were essential workers and were not able to maintain employment while participants in Boston were middle-high income and faced issues with out of pocket expenses or leave. While there are differences in the patient samples, both institutions care for a smaller proportion of preterm infants than community-based NICUs and have a different degree of illness acuity than the rest of the population. Moreover, cost of living is higher in both geographic areas suggesting that financial worry may be higher than other parts of the country affecting external generalizability of our results. Moreover, California and Massachusetts have substantially different insurance program infrastructures than other states. Specifically, in Massachusetts, Mass Health [47] combines Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program and California has the California Children’s Services program [48] which is state program to help children with certain diagnoses or conditions connect to services. While both these programs assist low-income families and children with special health care needs, low to middle-income families with private insurance may still experience significant financial worry.

In terms of limitations, we had a few survey items regarding socio-demographics that participants did not respond to although this was usually <15%. One must also consider the limitations regarding recall bias with a survey-based study (such as over-reporting use of social services) and that there was likely selection bias since there were missed referrals to the study. Moreover, we only included English or Spanish speaking families. Also, since our sample was collected in 2011–2015, it predates the use of rideshare, which may make up a higher proportion of non-medical costs now and does not reflect the shifting landscape of employment, leave and support that the COVID-19 pandemic surfaced. It also does not account for tele-health or virtual visits, which may actually reduce out-of-pocket transportation costs. Moreover our survey did not include free text responses where families might have included other expenses not listed. While we queried families about insurance status, we did not specify regarding receipt of high-deductible health plans. And though we used a validated survey, there are other instruments that might also capture financial burdens, such as the “COST” and “Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Financial Well Being Scale” [https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2017/01/13/cost-raising-child]. While we did not have a full term healthy cohort control in comparison, we wanted to elicit the experience of parents and families of preterm infants since several of the characteristics we identified are specific only to this population. Arguably, there would be similar burdens faced by families with term high risk infants. According to the Consumer Expenditures Survey, a middle-income family will spend $12,980 annually to raise a child without medical complexity [https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2017/01/13/cost-raising-child]. Here, we present information around wage losses, employment, transportation, and child care that may add to already existing concerns around financial planning for a family with a newborn.

The results from this study imply that families continue to face significant challenges with financial burden and worry after NICU discharge. Specific recommendations to target family financial assistance include:

-

(1)

Engage families in cost conversations in the NICU with a financial counselor to understand family income and insurance plans to create targeted financial assistance (low-income vs. high income, public vs. private insurance, deductibles, etc). Discussions should take place when a child is medically stable and occur at the bedside with optional supplemental written materials.

-

(2)

Provide more resources to strengthen the infrastructure in NICUs (for example, to social workers) to help screen, inform, and enroll families in SSI before NICU discharge.

-

(3)

Screen for underinsurance (i.e., can families afford prescriptions, specialty visits, etc.) at primary care or high risk infant follow up visits. This may improve care coordination within the family-centered medical home or with the primary care provider to ensure payment for needed services for children with special health care needs in particular.

-

(4)

Offer health exchanges with cost-calculators and price transparency tools to provide families with more information when choosing health plans.

Conclusions

Financial worry was common among families after NICU discharge. We identified several specific areas where families experienced financial strain such as paid leave and out-of-pocket expenses. The observations in this study may advise future work to target cost conversations and financial support systems, and more immediately to increase screening and enrollment in existing cash benefit programs such as SSI.

References

Russell RB, Green NS, Steiner CA, Meikle S, Howse JL, Poschman K, et al. Cost of hospitalization for preterm and low birth weight infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1–9.

Behrman RE, Butler AS. Preterm birth: causes, consequences, and prevention. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

King BC, Mowitz ME, Zupancic JAF. The financial burden on families of infants requiring neonatal intensive care. Semin Perinatol. 2021;45:151394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151394. Epub 2021 Jan 27.

Hodek JM, von der Schulenburg JM, Mittendorf T. Measuring economic consequences of preterm birth - Methodological recommendations for the evaluation of personal burden on children and their caregivers. Health Econ Rev. 2011;1(1):6.

Nuffield. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Critical Care Decisions in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine: Ethical Issues. 2006.

Carter J, Dwyer N, Roselund J, Cote K, Chase P, Martorana K, et al. Systematic changes to help parents of medically complex infants manage medical expenses. Adv Neonatal Care. 2017;17(6):461–9.

Johnston KM, Gooch K, Korol E, Vo P, Eyawo O, Bradt P, et al. The economic burden of prematurity in Canada. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:93.

Zupancic JAF. Burdens beyond biology for sick newborn infants and their families. Clin Perinatol. 2018;45:557–63.

Schiffman JK, Dukhovny D, Mowitz M, Kirpalani H, Mao W, Roberts R, et al. Quantifying the economic burden of neonatal illness on families of preterm infants in the U.S. and Canada. San Diego, CA: Pediatric Academic Societies; 2015.

Trang S, Zupancic JAF, Unger S, Kiss A, Bando N, Wong S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of supplemental donor milk versus formula for very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20170737. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0737.

Liu Y, McGowan E, Tucker R, Glasgow L, Kluckman M, Vohr B. Transition home plus program reduces medicaid spending and health care use for high-risk infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for 5 or more days. J Pediatr. 2018;200:91–7 e93.

Kuo DZ, Berry JG, Hall M, Lyle RE, Stille CJ. Health-care spending and utilization for children discharged from a neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2018;38:734–41.

Flores-Fenlon N, Song AY, Yeh A, Gateau K, Vanderbilt DL, Kipke M, et al. Smartphones and text messaging are associated with higher parent quality of life scores and enrollment in early intervention after NICU discharge. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58:903–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819848080. Epub 2019 May 14.

Lakshmanan A, Song AY, Flores-Fenlon N, Parti U, Vanderbilt DL, Friedlich PS, et al. Association of WIC participation and growth and developmental outcomes in high-risk infants. Clin Pediatr. 2020;59:53–61.

Lakshmanan A, Agni M, Lieu T, Fleegler E, Kipke M, Friedlich PS, et al. The impact of preterm birth <37 weeks on parents and families: a cross-sectional study in the 2 years after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:38.

Doty M, Rustgi SD, Schoen C, Collins SR. Maintaining health insurance during a recession: likely COBRA eligibility: an updated analysis using the Commonwealth Fund 2007 Biennial Health Insurance Survey. Issue Brief. 2009;49:1–12.

Doty MM, Collins SR, Nicholson JL, Rustgi SD. Failure to protect: why the individual insurance market is not a viable option for most U.S. families: findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2007. Issue Brief. 2009;62:1–16.

Doty MM, Collins SR, Rustgi SD, Nicholson JL. Out of options: why so many workers in small businesses lack affordable health insurance, and how health care reform can help. Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey. 2007 Issue Brief. 2009;67:1–22.

Rustgi SD, Doty MM, Collins SR. Women at risk: why many women are forgoing needed health care. An analysis of the Commonwealth Fund 2007 Biennial Health Insurance Survey. Issue Brief. 2009;52:1–12.

Wylie SA, Hassan A, Krull EG, Pikcilingis AB, Corliss HL, Woods ER, et al. Assessing and referring adolescents’ health-related social problems: qualitative evaluation of a novel web-based approach. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18:392–8.

Hassan A, Blood EA, Pikcilingis A, Krull EG, McNickles L, Marmon G, et al. Youths’ health-related social problems: concerns often overlooked during the medical visit. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:265–71.

Hassan A, Blood E, Pikcilingis A, Krull E, McNickles L, Marmon G, et al. Improving social determinants of health: effectiveness of a web-based intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:822–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.023. Epub 2015 Jul 26.

Hediger ML, Overpeck MD, Ruan WJ, Troendle JF. Birthweight and gestational age effects on motor and social development. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2002;16:33–46.

Belfort MB, Santo E, McCormick MC. Using parent questionnaires to assess neurodevelopment in former preterm infants: a validation study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:199–207.

Berry JG, Hall M, Neff J, Goodman D, Cohen E, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity and Medicaid: spending and cost savings. Health Aff. 2014;33:2199–206.

Als H, Behrman R, Checchia P, Denne S, Dennery P, Hall CB, et al. Preemie abandonment? Multidisciplinary experts consider how to best meet preemies needs at “preterm infants: a collaborative approach to specialized care” roundtable. Mod Healthc. 2007;37:17–24.

Petrou S. Economic consequences of preterm birth and low birthweight. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;110(Suppl 20):17–23.

McCormick MC, Bernbaum JC, Eisenberg JM, Kustra SL, Finnegan E. Costs incurred by parents of very low birth weight infants after the initial neonatal hospitalization. Pediatrics. 1991;88:533–41.

Koester KA, Morewitz M, Pearson C, Weeks J, Packard R, Estes M, et al. Patient navigation facilitates medical and social services engagement among HIV-infected individuals leaving jail and returning to the community. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28:82–90.

Silverstein M, Lamberto J, DePeau K, Grossman DC. “You get what you get”: unexpected findings about low-income parents’ negative experiences with community resources. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1141–8.

Jimenez ME, Barg FK, Guevara JP, Gerdes M, Fiks AG. Barriers to evaluation for early intervention services: parent and early intervention employee perspectives. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:551–7.

Jimenez ME, Fiks AG, Shah LR, Gerdes M, Ni AY, Pati S, et al. Factors associated with early intervention referral and evaluation: a mixed methods analysis. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:315–23.

Saul, A. Annual Report of Supplemental Security Income Program, 2020. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ssir/SSI20/ssi2020.pdf.

Pulcini CD, Perrin JM, Houtrow AJ, Sargent J, Shui A, Kuhlthau K. Examining trends and coexisting conditions among children qualifying for SSI under ADHD, ASD, and ID. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:439–43.

Kirchhoff AC, Parsons HM, Kuhlthau KA, Leisenring W, Donelan K, Warner EL, et al. Supplemental security income and social security disability insurance coverage among long-term childhood cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv057.

Lakshmanan A, Espinoza J, Kubicek K, Akineymi D, Williams R, Friedlich P, et al. Developing a resource navigation mobile (mHealth) application for transition-to-home from the NICU: a user-centered design approach. Baltimore, MD: Pediatric Academic Societies; 2019.

Feldman HM, Buysse CA, Hubner LM, Huffman LC, Loe IM. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 and children and youth with special health care needs. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36:207–17.

Kogan MD, Newacheck PW, Blumberg SJ, Ghandour RM, Singh GK, Strickland BB, et al. Underinsurance among children in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:841–51.

Perrin JM. Treating underinsurance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:881–3.

Pascoe JM, Stolfi A, Eberhart G, Khamis H. Parents’ report of their children’s underinsurance status After the affordable care act. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:208–15.

Moriates C, Shah NT, Arora VM. First, do no (financial) harm. JAMA. 2013;310:577–8.

Galbraith AA, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Rosenthal MB, Gay C, Lieu TA. Nearly half of families in high-deductible health plans whose members have chronic conditions face substantial financial burden. Health Aff. 2011;30:322–31.

Lemmon ME, Chapman I, Malcolm W, Kelley K, Shaw RJ, Milazzo A, et al. Beyond the first wave: consequences of COVID-19 on high-risk infants and families. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:1283–8.

Galbraith AA, Sinaiko AD, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Dutta-Linn MM, Lieu TA. Some families who purchased health coverage through the Massachusetts Connector wound up with high financial burdens. Health Aff. 2013;32:974–83.

Mader K, Sammen JM, Klene C, Nguyen J, Simpson M, Ruland SL, et al. Community-designed messaging interventions to improve cost-of-care conversations in settings serving low-income, Latino populations. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:S79–86.

Beck J, Wignall J, Jacob-Files E, Tchou MJ, Schroeder A, Henrikson NB, et al. Parent attitudes and preferences for discussing health care costs in the inpatient setting. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20184029. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-4029. Epub 2019 Jul 3.

Mass Health. 2021. https://www.mass.gov/topics/masshealth.

Services CC. 2021. https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/ccs/Pages/default.aspx.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge: the support of the Teresa and Byron Pollitt Family Chair in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, Sylvia Magallon, RN for her assistance as the manager of the High Risk Infant Follow Up Program at the Fetal and Neonatal Institute and Brooke Corder at Boston Children’s Hospital for their assistance with recruitment, Ms. Griselda Monroy, Ms. Rachel Polcyn, and Ms. Bernadette Lam for their assistance with data collection. We would like to thank Drs. Tracy Lieu, Alison Gailbraith, and Dr. Karen Kulthau for their contribution to study design and survey development. Finally, we would like to thank the families who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Richardson Fund with the Department of Neonatology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston MA, the Program for Patient Safety and Quality (PPSQ) at Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, the Medical Staff Organization at Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, the Confidence Foundation, the Saban Research Award and the Lucile Packard Young Investigator Award for Children with Special Health Care Needs. AL is supported by grants from the Sharon D. Lund Foundation and the Zumberge Diversity and Inclusion Award. The funder/sponsor did not participate in the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The corresponding author confirms that she has had full access to the data in the study. All authors hold final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The following are the contributions of each author: AL, AYS, MBB, LY, DD, PSF, and CLG—conceived and/or designed the work that led to the submission, and/or acquired data, and/or played an important role in interpreting the results. AL—drafted the manuscript. AL, AYS, MBB, LY, DD, and PSF—revised the manuscript; All authors—approved the final version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Boston Children’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles human subjects committees approved the study protocol.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lakshmanan, A., Song, A.Y., Belfort, M.B. et al. The financial burden experienced by families of preterm infants after NICU discharge. J Perinatol 42, 223–230 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01213-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01213-4

This article is cited by

-

Efficient administration of a combination of nifedipine and sildenafil citrate versus only nifedipine on clinical outcomes in women with threatened preterm labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Pediatrics (2024)

-

Unconditional cash transfers for preterm neonates: evidence, policy implications, and next steps for research

Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology (2024)

-

Measurement invariance analysis of the Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale - Research Short Form in mothers of premature and term infants

BMC Research Notes (2024)

-

The financial burden experienced by families during NICU hospitalization and after discharge: A single center, survey-based study

European Journal of Pediatrics (2023)