Abstract

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is the most serious complication after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD). Recently, Blumgart anastomosis (BA) has been found to have some advantages in terms of decreasing POPF compared with other pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) using either the duct-to-mucosa or invagination approach. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the safety and effectiveness of BA versus non-Blumgart anastomosis after PD. The PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science and the Cochrane Central Library were systematically searched for studies published from January 2000 to March 2020. One RCT and ten retrospective comparative studies were included with 2412 patients, of whom 1155 (47.9%) underwent BA and 1257 (52.1%) underwent non-Blumgart anastomosis. BA was associated with significantly lower rates of grade B/C POPF (OR 0.38, 0.22 to 0.65; P = 0.004) than non-Blumgart anastomosis. Additionally, in the subgroup analysis, the grade B/C POPF was also reduced in BA group than the Kakita anastomosis group. There was no significant difference regarding grade B/C POPF in terms of soft pancreatic texture between the BA and non-Blumgart anastomosis groups. In conclusion, BA after PD was associated with a decreased risk of grade B/C POPF. Therefore, BA seems to be a valuable PJ to reduce POPF comparing with non-Blumgart anastomosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was reported by Whipple and colleagues1 in 1935, PD has been regarded as the standard surgical procedure for patients with either benign or malignant disease of the pancreatic head and/or periampullary region. This surgical method was considered one of the most challenging and complex abdominal operations. With advances in surgical techniques and perioperative management, the mortality caused by PD decreased to less than 5% in high-volume centres, while the rate of postoperative complications remained as high as 50%, especially postoperative pancreatic fistulas (POPF) and delayed gastric emptying (DGE)2.

POPF, ranging from 3 to 45% in high volume centres, was considered to be one of the most serious complications after PD3. This complication, as defined by the International Study Group for Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF), is divided into 2 major groups: clinically irrelevant fistula (i.e., biochemical leak) and clinically relevant pancreatic fistula requiring a change in postoperative management (i.e., grades B and C)4. POPF can lead to intra-abdominal abscess, sepsis and haemorrhage and to life-threatening conditions with mortality up to 40%5. Therefore, numerous methods have been used to decrease POPF in previous studies, including use of octreotide6 or fibrin sealants to pancreatic remnant7, occlusion of the pancreatic duct8, pancreatic duct stenting9, modification of the pancreaticojejunostomy(PJ) anastomosis (end-to-end versus end-to-side10, invagination versus duct-to-mucosa11, interrupted suture versus continuous suture12) and pancreaticogastrostomy (PG)13. However, the reconstruction technique was perhaps the most important factor to reduce POPF. Currently, definitive evidence on the optimal surgical anastomosis technique is not yet available.

PJ was commonly used in reconstruction after PD, but the incidence of POPF remained high. PJ was further divided into two main categories, namely, duct-to-mucosa or invagination (dunking)14. In 2000, a novel method of PJ that combined the principle of duct-to-mucosa with the transpancreatic U suture technique was first proposed by Blumgart15. As opposed to the other duct-to-mucosa anastomosis such as Cattell-Warren anastomosis (CWA)16 and Kakita anastomosis (KA)17, U-sutures and the horizontal mattress suture technique was used in BA. The difference was that the Blumgart technique involved placement of 3–6 transpancreatic and jejunal seromuscular U-sutures to approximate the pancreas stump and the jejunum18,19. The BA has been reported to decrease the rate of grade B/C POPF to 0.67–7.14%20,21,22, significantly lower than the 10–20% in other reconstruction methods. The advantage of this technique was that U suture could avoid tangential shearing force23,24. Previously, BA has been reported with the advantage of reducing POPF in few case series or non-comparative retrospective studies18,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,29. At the same time, only one RCT30 and some retrospective comparative studies19,24,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 have been reported for comparison between BA and other PJ. Among some comparative studies19,31,32,34,35,36,37,38, POPF was reported to be lower in the BA group; however, other studies24,30,33 found no difference between the two methods. Previously, a review39 was published that only described a comparison between BA and KA. At present, some comparative studies focusing on BA with CWA or invagination PJ have been published. Therefore, we conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the safety and effectiveness of BA with that of conventional PJ after PD.

Results

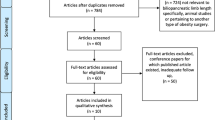

Study selection

In total, 45 studies were identified from the electronic databases, and 6 studies were excluded because they were duplicate publications. After screening the titles and abstracts, 10 records were excluded (including studies of irrelevant40,41,42,43,44,45, non-English46,47 and only abstracts48,49). The full texts of the remaining 29 records were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 18 were excluded because they were trial protocols50,51,52,53, review39, letter54, studies with no comparison with BA18,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,29 and studies related with BA versus pancreaticogastrostomy55,56. Ultimately, one RCT30 (from Asia) and ten non-randomized comparative studies (2 from Europe19,38 and 8 from Asia24,31,32,33,34,35,36,37) involving a total of 2412 patients were included in the quantitative syntheses. The process by which comparative studies were selected for inclusion in the present meta-analysis is shown in Fig. 1.

Trial characteristics and study population

The characteristics of the included eleven studies in the meta-analysis are presented in Table 1. All studies were published between 2009 and 2019. In total, eleven studies were included with 2412 patients, of whom 1155 (47.9%) underwent BA and 1257 (52.1%) underwent non-Blumgart PJ (including 274 (21.8%) with CWA19,24,34,38, 672 (53.5%) with KA31,32,33,34,37 and 127 (10.1%) with invagination PJ36,38). The sample sizes ranged from 87 to 374 patients in individual studies. Four studies focused on the rate of POPF in soft pancreatic texture30,32,33,34 and eight reported the use of pancreatic duct stents, either internal or external24,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Octreotide was used in five studies selectively19,24,30,37,38. Both PD and pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) were reported in eleven trials and only seven studies had concomitant PV/SMV resection24,30,31,32,34,35,38. Three main methods were reported for the non-Blumgart PJ, including CWA, KA and invagination anastomosis. The ISGPF (2005) and ISGPF (2017) definitions were used in seven19,24,31,32,33,34,37 and four studies30,35,36,38, respectively. The surgical techniques and definitions of POPF are shown in Table 2.

Methodological quality of included studies

The quality assessment score of the included studies is shown in Table 1. The quality of only one RCT study was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook57. The RCT trial30 clearly reported allocation concealment methods, withdrawals, dropouts and losses to follow-up, while not describing any kind of blinding; so, we deemed it to carry an unclear risk. The methodological quality of the included non-RCT studies was evaluated as described by McKay and colleagues58.

Results of the meta-analysis and subgroup analysis

BA versus non-Blumgart anastomosis

Primary outcomes

The forest plots of the primary outcomes are shown in Fig. 2. All included studies reported POPF (grade B or C), while only 4 studies reported grade A or biochemical leak POPF. Therefore, we only summarized and reported the rate of grade B/C POPF. Although some degree of heterogeneity was present among these studies (I2 = 76 per cent), the use of the random-effects model did not change the result. The BA group was associated with significantly lower rates of POPF (grade B/C) (OR 0.38, 0.22 to 0.65; P = 0.004) and POPF (grade B/C) using 2017 ISGPF definition (OR 0.58, 0.39 to 0.87; P = 0.008) than non-Blumgart group. However, there was no difference in the rate of POPF (grade B/C) in soft pancreatic texture and grade C POPF between the two groups.

Secondary outcomes

The pooled results of the secondary outcomes of BA group versus non-Blumgart group are summarized in Table 3. In the study of Kojima34, conventional PJ was divided into the CWA and KA groups. The duration of the operation was significantly longer as result of the additional operation including abdominal lavage and covering the wound and drain with dressing materials; therefore, it was removed from the sensitivity analysis. In addition, the intraoperative blood loss and postoperative hospital stay were reported in the study of Kojima in the CWA and KA groups. In summary, BA were associated with significantly lower rates of overall postoperative haemorrhage (OR 0.48, 0.29 to 0.79; P = 0.004), intra-abdominal abscess (OR 0.53, 0.39 to 0.72; P < 0.0001), morbidity (OR = -0.15, -0.29 to -0.01; P = 0.04), and reoperation (OR 0.50, 0.30 to 0.81; P = 0.005) and a shorter postoperative hospital stay (Kojima-CWA group: (WMD -4.43, -7.72 to -1.15, P = 0.008; Kojima-KA group: (WMD -3.51, -6.35 to -0.68; P = 0.02). However, there were no statistically significant differences in operative time, intraoperative blood loss or other postoperative complications (DGE, bile leakage, wound infection, major morbidity and mortality) between the two groups.

BA versus Cattell–Warren anastomosis

Primary outcomes

After careful analysis, in total, four studies were related to BA versus CWA19,24,34,38. Detailed results are presented in Table 4 and Appendix 1. Synthesis analysis of these studies suggested that BA had significantly lower incidence of POPF (grade B/C) (OR 0.28, 0.15 to 0·52; P < 0.0001) than did CWA. However, there was no significant difference in grade C POPF.

Secondary outcomes

BA was associated with significantly lower rates of postoperative haemorrhage (OR 0.29, 0.12 to 0.72; P = 0.008), DGE (OR 0.26, 0.10 to 0.68; P = 0.006), intra-abdominal abscess (OR 0.53, 0.29 to 0.98; P = 0.04), mortality (OR 0.18, 0.05 to 0.65; P = 0.009), and reoperation (OR 0.16, 0.06 to 0.42; P = 0.0002) as well as shorter operative time (WMD -57.99, -114.22 to 1.76; P = 0.04) than the CWA group. There were no significant differences in other outcomes between the two groups.

BA versus Kakita anastomosis

Primary outcomes

Comparisons of BA with KA were reported in five studies31,32,33,34,37. Detailed results are presented in Appendix 1 and Table 4. Compared with KA, BA was associated with a significantly lower incidence of POPF (grade B/C) (OR 0.26, 0.09 to 0.74; P = 0.01). No significant difference was observed in POPF (grade B/C) in soft pancreas or grade C POPF.

Secondary outcomes

The rates of intra-abdominal abscess (OR 0.36, 0.23 to 0.56; P < 0.00001) and wound infection (OR 0.44, 0.28 to 0.69; P = 0.004) were lower in the BA group. Moreover, the BA had significantly less intraoperative blood loss (WMD − 34.28, − 62.35 to − 6.02; P = 0.02), shorter operative time (WMD − 19.08, − 32.11 to − 6.05; P = 0.004) and postoperative hospital stay (WMD − 6.44, − 12.50 to − 0.39; P = 0.04). There were no significant differences in other outcomes.

BA versus invagination PJ

Only two studies36,38 could be used for this issue. The results are shown in Table 4 and Appendix 1. BA was associated with significantly lower rates of POPF (grade B/C) (OR 0.43, 0.21 to 0.76; P = 0.004), grade C POPF (OR 0.24, 0.06 to 0.89; P = 0.03) and reoperation (OR 0.41, 0.18 to 0.90; P = 0.03), as well as shorter postoperative hospital stay (WMD − 9.80, − 15.19 to − 4.14; P = 0.0004) than invagination PJ. However, major morbidity and mortality were comparable between the two approaches.

Publication bias

To examine any publication bias in the included studies, a funnel plot was constructed using the Review Manager 5.3. The funnel plot based on grade B/C POPF is shown in Fig. 3. The funnel plot was asymmetric; therefore publication bias might exist.

Discussion

Until now, the optimal reconstruction technique for PJ after PD has remained controversial59. This systematic review and meta-analysis not only made a comparison between BA and non-Blumgart PJ, but it also compared BA with CWA, KA and invagination PJ. This study suggested that the rates of grade B/C POPF, morbidity and postoperative haemorrhage were significantly lower in the BA group than in the non-Blumgart group. Therefore, BA appeared to be a safe, feasible and effective PJ technique compared to non-Blumgart PJ.

According to the previous reports, there are a number of plausible explanations for why BA was superior to a non-Blumgart anastomosis procedure in reducing the POPF rate. First, BA reduces tangential tension and shear force at the pancreatic stump via the use of the transpancreatic U-sutures. Second, BA maintains the pancreatic stump with a sufficient blood supply by interrupted mattress U-sutures. Furthermore, BA guarantees a tension-free approximation between the posterior and anterior seromuscular jejunum and excellent visualization of the pancreatic duct by placing a duct-to-mucosal suture at the beginning18,19,21,22,27,33. However, several drawbacks have also been reported regarding BA, especially for the original BA. King et al.28 reported that BA was incomplete and resulted in an unstable covering of pancreas stump that is prone to evoke POPF when joining a thin jejunum and a thick pancreas. To further achieve improvement, accumulated modifications of Blumgart anastomosis were proposed, including utilization of one suture for the anterior and posterior wall19, knot-tying on the ventral wall of the jejunum28,30, the use of closed drains and dressing materials to cover the wound and drains34, and a wide U-shape suture31 that minimized the space between the knots. Recently, Hirono et al.30 suggested that pancreatico-enteric anastomosis should use as few sutures as possible, taking care to not tie the suture too tightly and thus maintaining blood flow in the pancreatic stump.

The definition and classification of ISGPF was used in all the included studies. However, the ISGPF was updated in several studies, and the POPF grade A was called a “biochemical leak” because it has no significance in clinical practice. However, the definitions of grade B/C POPF are not very different between the 2005 and 2017 ISGPF. In addition, all included studies reported grade B or C POPF, while only 4 studies reported all POPF (including grade A or biochemical leak, grade B and grade C). Therefore, in the analysis of postoperative outcomes following PD, the present study mainly focused on grade B/C POPF60. In the present meta-analysis, the BA group had a lower rate of grade B/C POPF (8.3% vs 22.4%, P = 0.0004) than the non-Blumgart group, which was similar to the result of a previous study39. The incidences of grade B/C POPF after BA ranged from 0 to 30.8% as has been described in previous case series studies (Table 5). One of the important factors that affected the development of POPF was pancreatic texture. For soft pancreatic texture, the incidence of POPF (grade B/C) was lower in the BA group than in the conventional PJ group (27.3% versus 41.2%), although there was no statistically significant difference (OR 0.46, 0.14 to 1.53; P = 0.21).Therefore, it is possible that a soft pancreas led to a high incidence of pancreatic fistula, regardless of which way the PJ anastomosis was used.

Previous studies have suggested that POPF was the main cause for intra-abdominal abscess, postoperative haemorrhage and DGE after PD2. Thus, to some extent, it is clear that once the incidence of POPF decreases, perhaps postoperative morbidity would significantly decline. Our analyses indicated that the rates of intra-abdominal abscess and postoperative haemorrhage were significantly lower in the BA group (9.1% vs 16.5%, P < 0.0001), which was mainly due to the absence of dead space between the pancreatic cut surface and the jejunal wall in the U-suture technique group30. According to the results of the current meta-analysis, BA might significantly minimize the rate of reoperation (3.0% vs 4.9%, p = 0.005). The incidence of reoperation mainly resulted from severe complications including POPF (grade B/C), bleeding, and abscess formation. Therefore, the rate of overall postoperative morbidity and mortality in the BA group were 23.7% and 0.9%, respectively, less than in previous studies. At the same time, because of the decrease in complications, postoperative hospital stays were also reduced. The subgroup analysis that focused specifically on clinical trials comparing Blumgart anastomosis with other types of PJ anastomosis still favoured the advantages of BA.

There were some limitations in our meta-analysis that should be acknowledged. First, most included studies were retrospective before–after studies that inevitably led to selection bias. Second, the Blumgart technique was slightly different among studies with several modifications. Third, there was probably publication bias in the current study, mainly due to the unpublished studies with negative results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, compared with non-Blumgart PJ, BA was safer and more effective after PD with a lower incidence of grade B/C POPF, comparable operative time and intraoperative blood loss, lower morbidity and a shorter postoperative hospital stay. However, before recommending widespread use, it is necessary to design prospective multicenter, high quality RCTs to further test and verify the advantages of BA in patients with soft pancreas.

Materials and methods

Study design

The review was established according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines61. Two researchers (ZLL and ALW) independently conducted a comprehensive and systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science and the Cochrane Central Library from January 2000 (the first Blumgart anastomosis was described in 2000) to March 2020. The following search terms were chosen to screen databases, such as pancreaticoduodenectomy, pancreatoduodenectomy, Whipple, Blumgart, pancreaticojejunostomy, duct-to-mucosa and invagination along with their synonyms or abbreviations. The complete retrieval strategy in PubMed as follows:

-

#1 Pancreaticoduodenectomy [Mesh]

-

#2 Pancreaticoduodenectom*[tw] OR Pancreatoduodenectom*[tw] OR Duodenopancreatectom*[tw] OR Duodenum [tw] OR Pancreatectomy [tw] OR Whipple [tw]

-

#3 #1 OR #2

-

#4 Blumgart [tw]

-

#5 Pancreaticojejunostomy [Mesh]

-

#6 Pancreaticojejunostom*[tw] OR Pancreatojejunostom*[tw] OR duct-to-mucosa [tw] OR invagination [tw]

-

#7 #5 OR #6

-

#8 "2000/01/01"[dp]: "2020/03/31"[dp]

-

#9 #3 AND #4 AND #7 AND #8

Relevant papers have also been identified from the bibliographies of papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies were included based on the following criteria: English language articles published in peer-reviewed journals; human studies; studies with at least the primary outcome mentioned; only comparative clinical trials with full-text descriptions; clear documentation of the PJ technique and where multiple studies came from the same institute and/or authors, either the higher quality study or the more recent publication was included in the analysis. The following studies were excluded: abstracts, letters, editorials, expert opinions, case reports, reviews, trial protocols, and studies related to comparing BA with PG.

Outcomes of interests

Perioperative outcomes and postoperative complications were evaluated. The primary outcome measure was postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF). The POPF was defined according to the 200562 or 20174 International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) criteria. POPF (grade B/C) was a combination of grade B and C and was associated with a clinically relevant condition related directly to POPF. Secondary outcome included postoperative complications (postoperative haemorrhage, DGE, postoperative intra-abdominal abscess, wound infection, morbidity, mortality, reoperation) and perioperative outcomes (operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hospital stay). Bile leakage was defined as any biliary output via percutaneous drains after the first postoperative day, or detected at a reoperation. DGE and postoperative haemorrhage were defined and graded in accordance with the 2007 ISGPS criteria63,64. Postoperative morbidity was defined as total complications from date of operation to discharge. According to the modified Clavien-Dindo classification63,64,65, the Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3 complications were regarded as major morbidity. Mortality was defined as the number of deaths from any cause occurring in hospital or within 30 days after operation. Reoperation was defined as the need for laparotomy as a consequence of the first operation.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers using standard forms and were cross-checked. Inconsistencies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached, or a third reviewer would take part in the discussion. The RCT was assessed according to the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook57. The scoring system included the following criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of the results assessment, incomplete data of the results, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Observational studies were assessed as described by McKay and colleagues58, including assessment of data collection (prospective versus retrospective), assignment to BA or non-Blumgart PJ group by means other than the surgeon’s preference, and an explicit definition of POPF (studies were given a score of 1 for each of these areas, giving a total score of 1–4). Continuous variables were presented as the mean with corresponding standard deviations to be pooled in the meta-analysis. When the trials had reported medians and ranges instead of means and standard deviations, the estimation methods were used basing on the literature66,67.

Quantitative data was extracted from the selected studies, including population characteristics (age, gender, BMI), intraoperative conditions (type of anastomosis, pancreatic texture, mean main pancreatic diameter, operative time and intraoperative blood loss) and postoperative parameters (POPF(grade B/C), DGE, intra-abdominal abscess, bile leakage, wound infection, morbidity, mortality, reoperation, duration of drainage and postoperative hospital stay) in each study.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using Review Manager 5 software (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Heterogeneity was evaluated by means of the χ2 test, with P ≤ 0.10 considered to represent a significant difference. I2 values were used for the evaluation of statistical heterogeneity; an I2 value of 50% or more indicated the presence of heterogeneity68. Initially, a fixed-effects model was used to synthesize all data. With regard to outcomes when significant heterogeneity existed across studies, sensitivity analysis was performed by sequentially omitting each study to test the influence of an individual study on pooled data. However, if there was evidence of heterogeneity among the included studies, random-effects analysis according to DerSimonian and Laird69 was used. Clinical heterogeneity could be explained by different definitions of outcome parameters, and variability of interventions and perioperative management. The result of meta-analysis was presented as WMD or OR with 95%confidence intervals (CI). Data analysis was performed by comparing BA versus non-Blumgart PJ (including CWA, KA and invagination PJ). Funnel plots were constructed to evaluate potential publication bias, based on the grade B/C POPF.

References

Whipple, A. O., Parsons, W. B. & Mullins, C. R. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Ann. Surg. 102, 763–779. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-193510000-00023 (1935).

Kawai, M. & Yamaue, H. Analysis of clinical trials evaluating complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a new era of pancreatic surgery. Surg. Today 40, 1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-009-4245-9 (2010).

Cameron, J. L., Riall, T. S., Coleman, J. & Belcher, K. A. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann. Surg. 244, 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000217673.04165.ea (2006).

Bassi, C. et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery 161, 584–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014 (2017).

Kawaida, H. et al. Surgical techniques and postoperative management to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery. World J. Gastroenterol. 25, 3722–3737. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3722 (2019).

You, D. D., Paik, K. Y., Park, I. Y. & Yoo, Y. K. Randomized controlled study of the effect of octreotide on pancreatic exocrine secretion and pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. Asian J. Surg. 42, 458–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2018.08.006 (2019).

Deng, Y. et al. Fibrin sealants for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreatic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, 09621. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009621.pub4 (2020).

Mazzaferro, V. et al. Permanent pancreatic duct occlusion with neoprene-based glue injection after pancreatoduodenectomy at high risk of pancreatic fistula. Ann. Surg. 270, 791–798. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003514 (2019).

Xiong, J. J. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after intraoperative pancreatic duct stent placement during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br. J. Surg. 99, 1050–1061. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8788 (2012).

Ratnayake, C. B. B. et al. Critical appraisal of the techniques of pancreatic anastomosis following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a network meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 73, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.12.003 (2020).

Kone, L. B., Maker, V. K., Banulescu, M. & Maker, A. V. A propensity score analysis of over 12,000 pancreaticojejunal anastomoses after pancreaticoduodenectomy: does technique impact the clinically relevant fistula rate?. HPB (Oxford) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2020.01.002 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Continuous versus interrupted suture techniques of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J. Surg. Res. 193, 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.066 (2015).

Andrianello, S. et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy with externalized stent vs pancreaticogastrostomy with externalized stent for patients with high-risk pancreatic anastomosis: a single-center, phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.6035 (2020).

Kim, M., Shin, W. Y., Lee, K. Y. & Ahn, S. I. An intuitive method of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: use of one-step circumferential interrupted sutures. Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 21, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.14701/ahbps.2017.21.1.39 (2017).

Blumgart, L. H. & Fong, Y. Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract 3rd edn. (Saunders Co Ltd., New York, 2000).

Warren, K. W. & Cattell, R. B. Basic techniques in pancreatic surgery. Surg Clin North Am 36, 707–724 (1956).

Kakita, A., Takahashi, T., Yoshida, M. & Furuta, K. A simpler and more reliable technique of pancreatojejunal anastomosis. Surg. Today 26, 532–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00311562 (1996).

Mishra, P. K., Saluja, S. S., Gupta, M., Rajalingam, R. & Pattnaik, P. Blumgart’s technique of pancreaticojejunostomy: an appraisal. Dig. Surg. 28, 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1159/000329584 (2011).

Kleespies, A. et al. Blumgart anastomosis for pancreaticojejunostomy minimizes severe complications after pancreatic head resection. Br. J. Surg. 96, 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6634 (2009).

Grobmyer, S. R., Kooby, D., Blumgart, L. H. & Hochwald, S. N. Novel pancreaticojejunostomy with a low rate of anastomotic failure-related complications. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 210, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.020 (2010).

Lee, W. J. Fish-mouth closure of the pancreatic stump and parachuting of the pancreatic end with double u trans-pancreatic sutures for Pancreatico-Jejunostomy. Yonsei Med. J. 59, 872–878. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2018.59.7.872 (2018).

Tewari, M. et al. Outcome of 150 consecutive Blumgart’s pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 10, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-018-0821-z (2019).

Gupta, V. et al. Blumgart’s technique of pancreaticojejunostomy: analysis of safety and outcomes. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis. Int. 18, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbpd.2019.01.007 (2019).

Lee, Y. N. & Kim, W. Y. Comparison of Blumgart versus conventional duct-to-mucosa anastomosis for pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 22, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.14701/ahbps.2018.22.3.253 (2018).

Poves, I., Morato, O., Burdio, F. & Grande, L. Laparoscopic-adapted Blumgart pancreaticojejunostomy in laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg. Endosc. 31, 2837–2845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5294-y (2017).

Wang, S. E., Shyr, B. U., Chen, S. C. & Shyr, Y. M. Comparison between robotic and open pancreaticoduodenectomy with modified Blumgart pancreaticojejunostomy: a propensity score-matched study. Surgery 164, 1162–1167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2018.06.031 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Modified Blumgart anastomosis without pancreatic duct-to-jejunum mucosa anastomosis for pancreatoduodenectomy: a feasible and safe novel technique. Cancer Biol. Med. 15, 79–87. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2017.0153 (2018).

Kim, S. G., Paik, K. Y. & Oh, J. S. The vulnerable point of modified blumgart pancreaticojejunostomy regarding pancreatic fistula learned from 50 consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann. Transl. Med. 7, 630. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.10.89 (2019).

Nagakawa, Y. et al. Blumgart method using LAPRA-TY clips facilitates pancreaticojejunostomy in laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Medicine (Baltimore) 99, 19474. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000019474 (2020).

Hirono, S. et al. Modified blumgart mattress suture versus conventional interrupted suture in pancreaticojejunostomy during pancreaticoduodenectomy: randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 269, 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002802 (2019).

Fujii, T. et al. Modified Blumgart anastomosis for pancreaticojejunostomy: technical improvement in matched historical control study. J. Gastrointest Surg. 18, 1108–1115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2523-3 (2014).

Oda, T. et al. The tight adaptation at pancreatic anastomosis without parenchymal laceration: an institutional experience in introducing and modifying the new procedure. World J. Surg. 39, 2014–2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3075-8 (2015).

Kawakatsu, S. et al. Comparison of pancreatojejunostomy techniques in patients with a soft pancreas: Kakita anastomosis and Blumgart anastomosis. BMC Surg. 18, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-018-0420-5 (2018).

Kojima, T., Niguma, T., Watanabe, N., Sakata, T. & Mimura, T. Modified Blumgart anastomosis with the “complete packing method” reduces the incidence of pancreatic fistula and complications after resection of the head of the pancreas. Am. J. Surg. 216, 941–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.03.024 (2018).

Li, R., Zhang, W. & Li, Q. Modified pancreatojejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy for the treatment of periampullary tumor: 8 years of surgical experience. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 3788–3795. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.916837 (2019).

Li, Y. T. et al. Effect of Blumgart anastomosis in reducing the incidence rate of pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. World J. Gastroenterol. 25, 2514–2523. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i20.2514 (2019).

Satoi, S. et al. Does modified Blumgart anastomosis without intra-pancreatic ductal stenting reduce post-operative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticojejunostomy?. Asian J. Surg. 42, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2018.06.008 (2019).

Casadei, R. et al. Comparison of blumgart anastomosis with duct-to-mucosa anastomosis and invagination pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-center propensity score matching analysis. J. Gastrointest Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04528-3 (2020).

Cao, F., Tong, X., Li, A., Li, J. & Li, F. Meta-analysis of modified Blumgart anastomosis and interrupted transpancreatic suture in pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Asian J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2020.01.011 (2020).

Hawkins, W. G. et al. Caudate hepatectomy for cancer: a single institution experience with 150 patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 200, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.10.036 (2005).

Grobmyer, S. R. et al. Roux-en-Y reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch. Surg. 143, 1184–1188. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2008.501 (2008).

Fischer, M. et al. Relationship between intraoperative fluid administration and perioperative outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective randomized trial of acute normovolemic hemodilution compared with standard intraoperative management. Ann. Surg. 252, 952–958. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ff36b1 (2010).

Fujii, T. et al. Modified blumgart suturing technique for remnant closure after distal pancreatectomy: a propensity score-matched analysis. J. Gastrointest Surg. 20, 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-015-2980-3 (2016).

Gowda, N., Pendlimari, R. & Sushrutha, C. S. Critical sutures in hepatico-jejunostomy. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sci. 24, 180 (2017).

Tomimaru, Y. et al. Factors affecting healing time of postoperative pancreatic fistula in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 10, 435–440. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2019.1812 (2019).

Fujii, T. & Sugimoto, H. Modified Blumgart suturing technique (Nagoya Method) in pancreaticojejunostomy. Nihon Geka Gakkai zasshi 118, 203–205 (2017).

Losada, M. H., Curito, S. S., Troncoso, A., Herrera, C. H. & Silva, A. J. Pancreatoyeyunoanastomosis con técnica de Blumgart modificada para reconstrucción post-pancreatoduodenectomía. Estudio de serie de casos con seguimiento. Revista chilena de cirugía 70, 133 (2018).

Popp, F. C. & Bruns, C. J. Range of variation of pancreaticojejunostomy in pancreatic head resection. Der Chirurg Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen 88, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-016-0327-6 (2017).

Sata, N. Modified Blumgart technique of pancreatojejunostomyblumgart-dumpling method). Nihon Geka Gakkai zasshi 118, 198–202 (2017).

50Nct. Cattell-Warren Versus Blumgart Techniques of Pancreatico-jejunostomy Following Pancreato-duodenectomy. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02457156 (2015).

Halloran, C. M. et al. PANasta Trial; Cattell Warren versus Blumgart techniques of panreatico-jejunostomy following pancreato-duodenectomy: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 17, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1144-9 (2016).

52ChiCtr. Single-layer continuous anastomosis Versus Blumgart anastomosis in Pancreaticojejunostomy After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a Randomized Clinical Trial. https://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ChiCTR1800020086 (2018).

Hirono, S. et al. Modified Blumgart mattress suture versus conventional interrupted suture in pancreaticojejunostomy during pancreaticoduodenectomy: randomized controlled trial. HPB 21, S201–S202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2019.10.1565 (2019).

54Grobmyer, S. R., Kooby, D. A., Hochwald, S. N. & Blumgart, L. H. Blumgart anastomosis for pancreaticojejunostomy minimizes severe complications after pancreatic head resection (Br J Surg 2009; 96: 741–750). Br J Surg 97, 134; author reply 134–135, doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6953 (2010).

Kim, D. J., Paik, K. Y., Kim, W. & Kim, E. K. The effect of modified pancreaticojejunostomy for reducing the pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 61, 1421–1425 (2014).

Wang, S. E., Chen, S. C., Shyr, B. U. & Shyr, Y. M. Comparison of Modified Blumgart pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreaticogastrostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 18, 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2015.09.007 (2016).

Higgins, J. et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343, d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928 (2011).

McKay, A. et al. Meta-analysis of pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br. J. Surg. 93, 929–936. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.5407 (2006).

Olakowski, M., Grudzinska, E. & Mrowiec, S. Pancreaticojejunostomy-a review of modern techniques. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 405, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-020-01855-6 (2020).

Smits, F. J. et al. Management of severe pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. JAMA Surg. 152, 540–548. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5708 (2017).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 (2009).

Bassi, C. et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 138, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001 (2005).

Wente, M. N. et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 142, 761–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005 (2007).

Wente, M. N. et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery 142, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001 (2007).

Dindo, D., Demartines, N. & Clavien, P. A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 240, 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae (2004).

Wan, X., Wang, W., Liu, J. & Tong, T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14, 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 (2014).

Luo, D., Wan, X., Liu, J. & Tong, T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 27, 1785–1805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280216669183 (2018).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.) 327, 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 (2003).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials 45, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology Supporting Project (No. 2018SZ0174), International Cooperation Project of Chengdu Science and Technology Bureau (No. 2019-GH02-00020-HZ) and 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC18027). This meta-analysis was registered at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/ prospero/under registration number CRD42020186246.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., A.W., J.X. and W.H. designed the study. Z.L. and A.W. performed the study and wrote the paper. N.X. and L.Z. assessed the study and collected the data. D.Y. and J.Y. analysed the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Wei, A., Xia, N. et al. Blumgart anastomosis reduces the incidence of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 10, 17896 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74812-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74812-4

This article is cited by

-

Usage of a simplified blumgart pancreaticojejunostomy in laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single center experience

BMC Surgery (2023)

-

Geriatric nutritional risk index as a potential prognostic marker for patients with resectable pancreatic cancer: a single-center, retrospective cohort study

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Predictors of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula (POPF) After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Clinical Significance of the Mean Platelet Volume (MPV)/Platelet Count Ratio as a New Predictor

Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery (2022)

-

Challenges of single-stage pancreatoduodenectomy: how to address pancreatogastrostomies with robotic-assisted surgery

Surgical Endoscopy (2022)

-

Reproduction of modified Blumgart pancreaticojejunostomy in a robotic environment: a simple clipless technique

Surgical Endoscopy (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.